The Revolution Wore Black: Protest Fashion in 19th-Century Poland

As daguerreotypes of insurgents in ‘czamary’ and mourning crinolines attest, fashion, design and photography became tools of resistance during the January Uprising.

Under the partitions, Poles resorted to a wide array of methods to demonstrate their devotion to the national-liberationist cause. One of these was fashion. During the Romantic era, for example, one could spot a revolutionary from the way his beard was trimmed. In Stanisław Wasylewski’s monumental work Życie Polskie w XIX Wieku (19th-Century Polish Life), he wrote:

This century’s history has been an almost incessant parade of costumed demonstrations […] Some items of clothing that seem trivial today were formerly […] instruments of politics and propaganda.

The 1860s were the peak of clothes as a form of passive resistance in Poland. The January Uprising was preceded by what Franciszek Ziejka termed a ‘mystical revolution’ of patriotic church services and special occasions, such as national anniversary celebrations and street rallies. After the Tsarist authorities’ bloody crackdown on peaceful protests in late February 1861, a call for national mourning began to circulate around Congress Poland (reputedly emanating from the archbishop of Warsaw).

Konstanty Gaszyński’s poem Czarna Sukienka (A Black Dress) – written after the collapse of the November Uprising thirty years earlier – became relevant once more:

Mother, put away my dresses,

Pearls and rosy garlands.

Dazzling garments, splendid costumes,

Are no more for me.

Flowers and finery once I adored,

Our hopes they did gush like a fountain;

But now as Poland lies stretched in her grave

Nothing will I ever wear again

But a black dress.

The new black

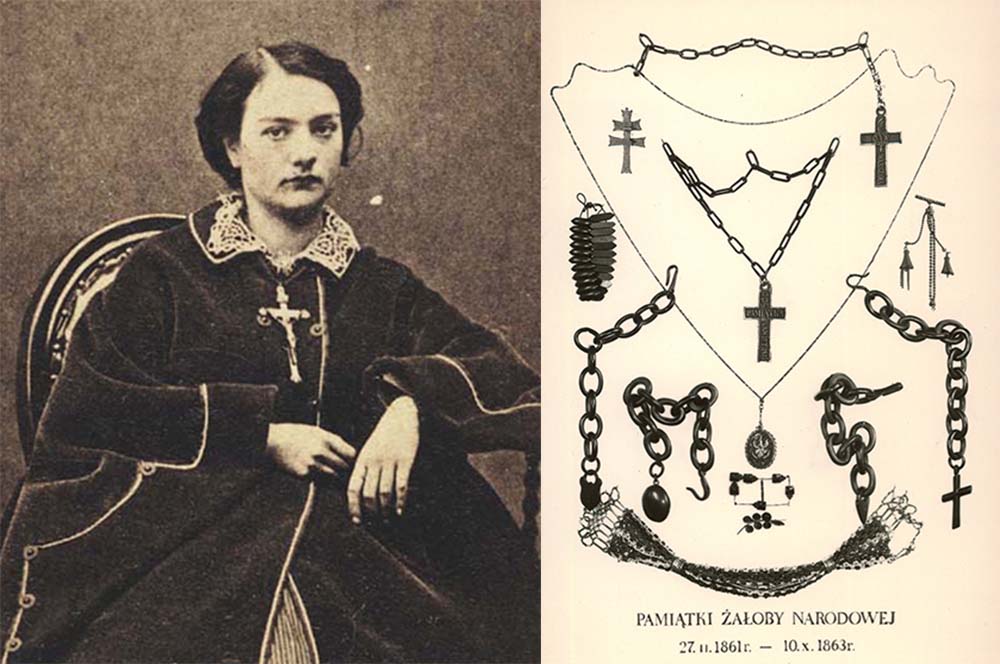

Portrait of Michalina Grabowska, 1863, photo: National Library / CBN Polona

Portrait of Michalina Grabowska, 1863, photo: National Library / CBN Polona‘All we see in the Warsaw magazines are black outfits, so we feel obliged to inform our Lady Readers about them’, wrote Magazyn Mód i Nowości Dotyczących Gospodarstwa Domowego (Magazine of Fashion and Household News) in 1861.

Nowadays, we tend to associate women’s clothing from that period with mourning. Some ladies even wore black to their own weddings. But black crinoline dresses often had another, practical function – as it was easy to hide smuggled publications or weapons under them. ‘Polish women are perpetual, relentless and incurable conspirators’, to quote the Russian writer Nikolai Vasilievich Berg.

Portrait of Henryka Pustowojtówna, wet collodion plate, facsimile 1864 (original 1863),

Portrait of Henryka Pustowojtówna, wet collodion plate, facsimile 1864 (original 1863),

‘Mementos of National Mourning 27/2/1861–10/10/1863’, photo: from the collection of Fr. Wal. ŚlusarczykDark outfits were decorated with mourning jewellery. The most popular themes included handcuff-like bracelets, buckles shaped like two clasped hands (symbolising the connection between Poland and Lithuania), anchors (symbolising hope), engraved portraits of Tadeusz Kościuszko, eagles wearing crowns of thorns, crucified scythes, and sometimes even skulls. There were also coded abbreviations, such as the letters R.O.M.O. on rings (Rozniecaj Ogień Miłości Ojczyzny – ‘Kindle the Fire of Love for Our Fatherland’). These ornaments were usually made of humble materials like wood, aluminium, copper or low-grade silver. Most gold had ‘gone for iron’, as they used to say, i.e. been donated to public collections for weapons to arm the insurgents.

Apart from wearing the obligatory black, men also had to forsake their top hats or don more modest headgear. Passers-by who failed to adopt this etiquette had their hats knocked off or flattened on their heads. References to other European revolutionary movements were all the rage, such as Magyar or Garibaldi hats. Stanisław Rybicki called this a ‘costume fetish’, writing:

Anyone not dressed in mourning, with a low-brimmed hat, is frowned upon and liable to bear the brunt of unpleasant remarks in the streets at every step.

National mourning soon swept almost the entire territory of the First Polish Republic. Joseph Conrad’s mother, Ewa Korzeniowska, described the prevailing mood in the streets of Żytomierz:

The mourning is so widespread that one hardly ever sees coloured dresses. Little Konrad used to wear our favourite tricolour [blue, white and red – the colours of the French Revolution], but now he has a mourning gown, and refuses to wear anything else to church.

In another letter, she wrote:

I will stop now. I’m exhausted: I spent the entire day sewing a mourning gown for Konrad. Everything is so dark, even the children. My youngest was pestering me about mourning, and it was my duty to indulge him.

The mourning even extended to … children’s toys! Przyjaciel Dzieci (Children’s Friend) magazine published a story for youngsters, Prawdziwa i Bardzo Ciekawa Historja o Lalce, Która Była za Modnie Ubraną… (The True and Fascinating Story of the Doll Who Was Too Fashionably Dressed…), the moral of which warned against wearing over-elegant frocks.

This atmosphere led to an unwritten code of behaviour. Dances and balls were deemed bad form, and music ceased to be played in cafés. Even organ grinders were driven out of the courtyards, and theatres were boycotted, which drew some criticism. Cyprian Kamil Norwid wrote: ‘Even during sieges and wars, ancient Greek cities never neglected their theatres’.

Solitary confinement for a crinoline

Polish women dressed for national mourning, photographed by Karol Beyer, pictured: Emilia ze Szwarców Heurichowa with her daughters, Teodora, Helena, Julia and Emilia, pre-1867, photo: from the archives of Jacek Dehnel

Polish women dressed for national mourning, photographed by Karol Beyer, pictured: Emilia ze Szwarców Heurichowa with her daughters, Teodora, Helena, Julia and Emilia, pre-1867, photo: from the archives of Jacek DehnelThese mourning costumes did not escape the notice of the authorities. Tsarist agents appeared in the streets, carrying special hooks to tear black crinoline dresses, and one risked large fines or arrest for flouting the edict. Women were only allowed to wear black if granted special official authorisation, obtainable if they could prove that a parent or husband had recently died. But the resistance persevered. When schoolgirls were banned from wearing black, they drew stripes on their necks and hands with black ink, calling it ‘unremovable mourning’. As the repression intensified, other colours – violet and grey – also came under fire.

The ban also spread into the other partitions. By April 1861, ‘mourning bows, Polish eagles, tricolour ribbons on watches and ties, rosettes, bows, canes with axe-heads, maces, and any other kind of political emblems’ had been outlawed in Lviv.

The press were also prohibited from reporting on the phenomenon. The aforementioned Magazyn Mód i Nowości Dotyczących Gospodarstwa Domowego found clever ways around the censorship by writing, for example: ‘Due to the death of the Princess of Kent, we shall only be featuring mourning clothes’. Another time, it recommended black outfits for bad weather, or during Lent.

Although mourning was not compulsory on ‘public holidays’ (anniversaries of important Polish historical events, such as 3rd May or Constitution Day), this did not please the authorities either:

People were clad in festive attire at Christian and Jewish religious services and in the streets. Women dressed in bright colours and men in white ties appeared clasping bunches of green twigs. That day, the police would have been glad to see everyone scruffily dressed, so they were incensed by this shameful gaiety, and arrested some 60 people for holding green leaves in their hands […] or for wearing white gloves.

So wrote Agaton Giller, an eyewitness to the events.

In order to tackle various sartorial tactics designed to evade the authorities’ ban, Friedrich von Berg, the Tsar’s viceroy, issued an edict in 1863, clearly stating what could and could not be worn:

Hats must be coloured, or – if black – must be decorated with flowers or coloured ribbons, but absolutely not white ones. Black and white feathers on black hats are forbidden. Hoods may be black with coloured linings, but not white ones. Black veils, gloves, or black or black-and-white umbrellas are not permitted, not to mention shawls, headscarves, bandanas and neckerchiefs, or fully black or black-and-white dresses. Mantles, overcoats, furs, raincoats and other outer wear may be black, but contain no white. Men cannot appear in mourning under any circumstances.

Despite the repression, various forms of mourning persisted until 1866, when the Tsar decreed an amnesty – although people would still be imprisoned for wearing black up until 1873.

Mourning in the studio

‘VIII: Żałobne Wieści’ (Mournful News) by Artur Grottger, from the ‘Polonia’ series, 1863, photo: the National Museum in Warsaw

‘VIII: Żałobne Wieści’ (Mournful News) by Artur Grottger, from the ‘Polonia’ series, 1863, photo: the National Museum in WarsawThe mourning turned out to be an excellent PR stunt which drew foreign attention to the situation in Poland. In Spain, black rosary beads became known as ‘Polish tears’. Even Karl Marx’s daughter is said to have worn a dark dress in solidarity with Polish women, together with an iron cross sent over from Poland.

Artur Grottger’s European tour also helped raise awareness of the cause. His Polonia series was exhibited in London, Paris and Vienna. While abroad, the artist would appear in January Uprising insurgent garb, complete with Confederate cap and a czamara. A Confederate cap was square with no peak, trimmed with sheepskin, and named after the Bar Confederation. It became a national symbol, and various versions were worn during Polish uprisings of the 19th century. The czamara was a ‘Persian outer coat which buttons up to the neck […] It was fashionable under [King] Stanisław August – especially during the Four-Year Sejm – and was somehow reminiscent of the national costume’, reported the ethnographer Łukasz Gołębiowski. Meanwhile, Adam Mickiewicz (who of course wore a Confederate cap and szamara himself) wrote in his Księgi Narodu Polskiego i Pielgrzymstwa Polskiego (The Books and the Pilgrimage of the Polish Nation):

Ye, both old and young, wear your revolutionary czamaras, for ye are all soldiers of the resurrection of your country.

Trans. James Ridgway

Such political declarations encouraged the spread of a new technology – photography. There are pictures of Norwid in Paris, sporting a Confederate cap. As he explained in one poem:

Upon my head I placed an amaranthine Confederate cap, for it was the cap which Piast used as a lining for his crown.

In Galicia, it was an expression of patriotic devotion to wear the traditional costume and robes of the nobility, since they were prohibited in Congress Poland. This is why many such photographs originated from there. The poet and translator Apollo Korzeniowski (and father of Joseph Conrad) went against this noble fashion somewhat by posing in peasant clothes at Karol Beyer’s photographic studio.

Women in mourning and men in insurgent costume flocked to studios in Warsaw, Kraków and Poznań, although there was often a sad, pragmatic reason for it – those daguerreotypes might have been the final keepsakes for the families of men leaving to join the uprising. Likewise, letters to Siberia often contained photographs of women in mourning.

Originally written in Polish, translated by Mark Bence, Jan 2021

Sources: 'Rosyjskie haki i polskie krynoliny. Żałoba narodowa 1863 roku', Daniel Brzeszcz, Warsaw 2015; 'Powstańcy styczniowi i zesłańcy syberyjscy', Krystyna Lejko, Warsaw 2004; 'Kochanek Justyny w Warszawie. Zbiór szkiców o dawnej Warszawie opartych na dokumentach, Janina Siwkowska, Warsaw 1967

Tytuł (nagłówek do zdjęcia)

[{"nid":"5688","uuid":"6aa9e079-0240-4dcb-9929-0d1cf55e03a5","type":"article","langcode":"en","field_event_date":"","title":"Challenges for Polish Prose in the Nineties","field_introduction":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary\r\n","field_summary":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary","topics_data":"a:2:{i:0;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259609\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:26:\u0022#language \u0026amp; literature\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:27:\u0022\/topics\/language-literature\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}i:1;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259644\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:8:\u0022#culture\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:14:\u0022\/topic\/culture\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}}","field_cover_display":"default","image_title":"","image_alt":"","image_360_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/360_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ZsoNNVXJ","image_260_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/260_auto_cover\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=pLlgriOu","image_560_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/560_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=0n3ZgoL3","image_860_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/860_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ELffe8-z","image_1160_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/1160_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=XazO3DM5","field_video_media":"","field_media_video_file":"","field_media_video_embed":"","field_gallery_pictures":"","field_duration":"","cover_height":"991","cover_width":"1000","cover_ratio_percent":"99.1","path":"en\/node\/5688","path_node":"\/en\/node\/5688"}]