Post-Mortem: The Story of Polish Mourning Portraits

Photographs of deceased children with eyes painted on, corpses propped up by systems of pegs and supports, Adam Mickiewicz on his deathbed, pictures of adolescents in coffins reproduced in the tens of thousands – Culture.pl explores the phenomenon of Polish post-mortem photography.

Long before Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the first photograph in 1826, and the new medium of photography spread around the world, people had been trying for centuries to capture the images of the deceased. They painted portraits of the departed and framed their locks of hair in silver and gold creating distinct jewellery. Several rituals accompanying death and burial were established: covering mirrors, stopping clocks, turning chairs upside down.

A mourning portrait of a woman in a white coif, photo: National Museum in Warsaw

A mourning portrait of a woman in a white coif, photo: National Museum in WarsawApproximately two hundred years before photography caught on in Poland, in the 17th and 18th centuries, so-called coffin portraits were especially popular. The paintings of the deceased were fixed on the front of the narrow sides of coffins. Globally unique, the phenomenon would have reigned in the ways of memorialising the dead in Poland, had it not been for Niépce’s invention.

The new technique spread rapidly and ravenously. The forerunner of the contemporary photography envisioned by Niépce in his atelier, the daguerreotype, was gaining recognition country by country. Before long, it found its way into rituals pertaining to death and burial.

Post-mortem photography, also known as mourning photography, achieved popularity in Poland as well. Portraits of the deceased began being taken in Poland in the 1840s. While, initially, the authors of such photos were concentrated on the dead themselves, they started capturing the entire ritual as well. Apart from making head-to-chest and head-to-torso photographs, the departed were portrayed in various ‘stage sets’ constructed with the use of flowers, candles, porcelain and other everyday objects.

Five Killed Men

Karol Beyer, Five Killed Men, post-mortem portraits of five fallen participants of the patriotic demonstration of 27th February 1861, photo: the National Library in Warsaw/CBN Polona

The first post-mortem photograph to enter Polish consciousness was Karol Beyer’s Five Killed Men taken in 1861. Beyer, an ethnic German, is called the father of Polish photography. He opened his first atelier in Warsaw in 1845, thus, becoming the pioneer of studio photography in the present capital of Poland, which was occupied by Russia at that time.

Since then, he photographed both the dead and the living. However, it was the work he created during the suppression of the 1861 anti-Tsarist demonstration that brought him fame. On 25th February 1861, the tsarist army was given orders by authorities to shoot five participants of the peaceful patriotic protest in Warsaw. Beyer photographed them a day later and created a distinctive tableau. ’Innumerable quantities of these cards were scattered around Poland’, the Russian journalist, Nikolai Vasilyevich Berg, wrote about the photographer’s work.

Jacek Dehnel notes that post-mortem photography played two important roles in this case. First, it was journalistic in character – it was a record of the tragic effects of the authorities’ activities. Second, it became a national relic – it consolidated and unified the nation.

The blank stare of the innocent

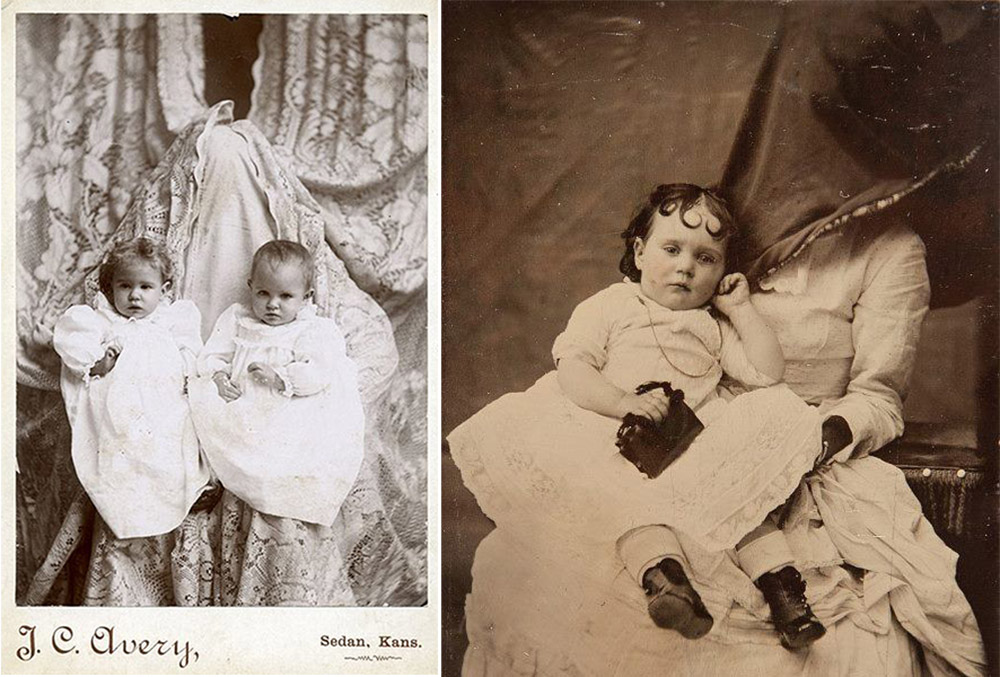

Photographs from ‘The Hidden Mother’ book, Lindy Fregni Nagler, photo: press materials

Photographs from ‘The Hidden Mother’ book, Lindy Fregni Nagler, photo: press materialsVictorian Britain, where having a photograph of a deceased family member was a natural occurrence, is an exemplary country which mastered the art of post-mortem portraiture. The staging involved creative solutions to achieve adequate compositions. The photographers used wooden pegs and string, which kept the body in position. Several preserved post-mortem photos depict lifeless children accompanied by the so-called ‘hidden mothers’. Fully veiled, the women held their children during the several-minutes-long process of the exposure of the photosensitive material to light. Even though their role was usually limited to keeping the living offspring still, some distressing photos show the hidden mother holding the body of a dead child accompanied by its living siblings.

Such measures were also taken in Polish ateliers. Due to high rates of infant mortality, parents often styled their deceased progeny in order to make them look alive. They often painted open eyes on the closed eyelids of their toddlers. Frequently, the dead child was placed next to the siblings who seemingly naturally held it up.

Mickiewicz asleep

Adam Mickiewicz on his deathbed in Constantinople, 1855, unknown author; photo: the Museum of Literature / East News

Adam Mickiewicz on his deathbed in Constantinople, 1855, unknown author; photo: the Museum of Literature / East News

However, ‘set up’ photos of deceased children were not a rarity. Often, the cadavers of adults were treated the same way. Their bodies were propped in peculiar poses. An arm was generally used as a support for a head, and adults were seated in an armchair or placed in a pensive pose.

Post-mortem photos were also taken with the bodies in a coffin or on a deathbed in order to depict the deceased as if they were sleeping. An example of such a composition is the mourning portrait of Adam Mickiewicz photographed by an unknown author in Constantinople in 1855. The Polish national poet is embraced by soft light, his crossed hands are relaxed and his face is ever so slightly turned towards the lens.

A veiled maiden crossing the Jordan

A young woman, post-mortem photography, photo: Whitehotpix/Forum

A young woman, post-mortem photography, photo: Whitehotpix/Forum Photographs of the perished in coffins evolved from austere shots of the 1840s into multi-plane, complex compositions in later years. A specific example is the stage set surrounding a young woman buried as a maiden. The coffin is adorned with pearly candles and flowers – often lilies, symbolising purity. The deceased woman would be buried in a white dress, which, at times, was embellished with a veil or a wreath. Depending on the financial situation of the family, apart from the coffin and the mourners, a photographer captured funeral wreaths, the mourning cortege and fragments of the ceremony.

Post-mortem photography’s second death

As photo cameras grew more advanced and the time of exposure of the photosensitive material to light was becoming shorter, the art of photography was becoming more and more popular. The first armed conflict to be captured was the Crimean War of 1853-1856 photographed by Robert Fenton. Since then, post-mortem photography entered a new stage. Documenting victims of the battlefront during both world wars, as well as, for example, the Spanish Civil War, led to the distinction of post- and pre-mortem photography.

Pre-mortem photographs illustrate death’s doorstep. These pictures precede death. One can deduce that the people depicted in these photos are actually already dead, even though they died outside of the frame. As Tomasz Ferenc describes:

Pre-mortem photographs are captivating because of the eyes of the ones suffering directed straight into the lens. Their stares are astonishingly intense and filled with agony. Post-mortem photographs overwhelm with their nobleness and the tranquil faces of the deceased, which are simultaneously stern and sunken.

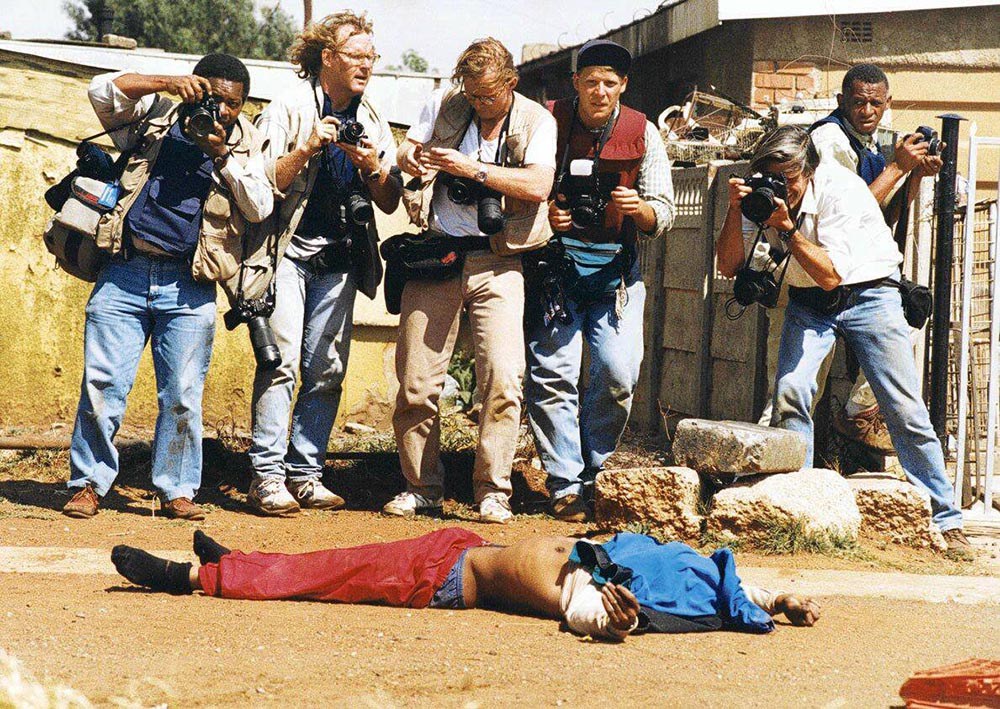

Johannesburg, South Africa, 19.04.1994, photo: Krzysztof Miller/Agencja Gazeta

Johannesburg, South Africa, 19.04.1994, photo: Krzysztof Miller/Agencja Gazeta

Of the Polish mortem photographers, Krzysztof Miller should be noted for his dedication to portraying war. Children dying of hunger, a swarm of reporters leaning over a still body of a man – ‘indecisive moments which will never change the fate of the victims’ as he called them. He started working as a war correspondent in the 1980s for the Polish daily newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza documenting armed conflicts in the Balkans, Chechnya, Afghanistan, South Africa and the famine in Africa.

Photography is death

For almost two centuries, death and photography have intertwined: starting with post-mortem portraits and ending with the coverage of the front lines in conflicts around the globe. In each of these contexts, the bromidic memento mori resonates strongly. However, not even the most renowned art theorists shy away from the reverberance. Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag and Boris von Brauchitsch emphasise that each photograph is in a way ‘burdened’ with death since it’s distanced from a ‘living’ image. After all, as Sontag puts it, ‘Life is a film. Photography is death.’

Originally written in Polish by Dagmara Staga, Oct 2017; translated by AP, May 2018

Sources: Memento Mori: Opowieść o Fotografii Post Mortem (Memento Mori: The Story of Post Mortem Photography) by Jacek Dehnel, a lecture in the History Meeting House in Warsaw; Culture.pl; Fotografia i Śmierć – Historia Pewnego Uwikłania i Realna Styczność (Photography and Death: The History of an Involvement and a Real Proximity) by Tomasz Ferenc in 'Kwartalnik Fotografia' 35 (2011)

[{"nid":"5688","uuid":"6aa9e079-0240-4dcb-9929-0d1cf55e03a5","type":"article","langcode":"en","field_event_date":"","title":"Challenges for Polish Prose in the Nineties","field_introduction":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary\r\n","field_summary":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary","topics_data":"a:2:{i:0;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259609\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:26:\u0022#language \u0026amp; literature\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:27:\u0022\/topics\/language-literature\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}i:1;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259644\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:8:\u0022#culture\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:14:\u0022\/topic\/culture\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}}","field_cover_display":"default","image_title":"","image_alt":"","image_360_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/360_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ZsoNNVXJ","image_260_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/260_auto_cover\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=pLlgriOu","image_560_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/560_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=0n3ZgoL3","image_860_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/860_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ELffe8-z","image_1160_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/1160_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=XazO3DM5","field_video_media":"","field_media_video_file":"","field_media_video_embed":"","field_gallery_pictures":"","field_duration":"","cover_height":"991","cover_width":"1000","cover_ratio_percent":"99.1","path":"en\/node\/5688","path_node":"\/en\/node\/5688"}]