Saying No to Children, Kitchen, Church: The Pioneers of Women’s Rights in Poland

Countless Polish heroines have fought against ‘women being sacrificed to the mercy of pots and brooms’. But the struggles of even the earliest feminists remain unfinished: many of their demands have yet to be fulfilled today.

It is the second half of the 19th century. Polish society lives across three annexed territories, the law in each one oppressive towards women. In the German part, there’s the rule ‘Kinder, Küche, Kirche’ (‘Children, Kitchen, Church’), and in Tsarist Russia, women are de facto subject to their husbands and fathers. Women have neither the right to vote, nor to attend school in any of the territories. In Galicia, they are barred from joining political associations.

At the same time, the failures of the period’s various uprisings have ushered in a kind of matriarchy. Many men have either died, been forced to emigrate, or been exiled to Siberia, so women have taken over the roles traditionally reserved for men.

It is against this backdrop that a feminist movement blossoms on Polish lands.

'Sistering' & the Enthusiasts

Portrait of Klementyna Hoffmanowa, 1834, photo: POLONA / www.polona.pl

Portrait of Klementyna Hoffmanowa, 1834, photo: POLONA / www.polona.pl

Klementyna Hoffmanowa is the figure that typically opens any conversation about the history of Polish feminism. It’s true that she was an independent woman, living only from her writing and pedagogical activity – which, in those days, was certainly rare.

But was she a feminist? She popularised education for girls, but her works parroted the traditional distribution of roles for men and women.

Narcyza Żmichowska. Photo: Piotr Mecik / Forum

Narcyza Żmichowska. Photo: Piotr Mecik / Forum

The real mutiny was fomented by her students, primarily Narcyza Żmichowska. After graduating from the Governesses' Institute in Warsaw, she became a live-in tutor for the Zamoyski family in Paris. Whilst there, she came into contact with the democratic movement and absorbed the ideas of the first wave of feminism. This led to the loss of her job.

Laundry day: a humorous photo from 1901, photo: Roger-Viollet / East News

Laundry day: a humorous photo from 1901, photo: Roger-Viollet / East News

Żmichowska returned to Poland a changed woman. She got involved in educational and public demonstrations, and she even served some time in prison. Her ‘male lifestyle’ – riding horses and smoking cigars – was considered shocking.

Żmichowska also gathered a circle of supporters that created an informal group called ‘Entuzjastki’ (‘The Enthusiasts’). Their aim was to increase female influence in public life and ensure equal access to education. They promoted ideas of self-fulfilment and economic independence. Żmichowska wrote:

Text

Study if you can. Learn, if you can, and consider earning enough to look after yourself. Because in times of need, nobody will be waiting with support and care.

Their texts were published in Pierwiosnek (Primrose). Described as ‘a magazine consisting solely of texts by ladies’, it was the first publication in Polish created strictly by women. The group's activities were based on Żmichowska's idea of ‘posiestrzenie’ (literally, ‘sistering’), an affirmation of platonic friendships between women. They also stood in opposition to arranged loveless marriages, which they viewed as little more than financial contracts between families.

Other members of the Entuzjastki group included Eleonora Ziemięcka (the first Polish female philosopher), and Bibiana Moraczewska, a writer and activist engaged in issues connected with society and independence – as well as a daring conspirator.

Entuzjastki's ideas bloomed over the next few generations. Also emerging from this period was Ewelina Porczyńska, the mother of Paulina Kuczalska-Reinschmit, who was dubbed the ‘hetman of Polish feminism’, and Wanda Grabowska (later Żieleńska), mother to Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, who became the key male feminist of the Second Polish Republic.

Demanding human rights

Maria Dulębianka on a pre-war postcard, photo: Cyfroteka

Maria Dulębianka on a pre-war postcard, photo: Cyfroteka

Amongst the many demands of the suffragette movement during the era of the partitions, two came strongly to the fore: political rights and equal access to education. The action that caused the biggest stir – today, we might call it a ‘performance’ came when Maria Dulębianka, a close companion of Maria Konopnicka, ran in the election for Galicia's Sejm in 1908. Dulębianka received more than 400 votes (from only men, of course), but despite this respectable result, her application was rejected 'for formal reasons'.

British suffragettes in 1913. Photo: AKG / East News

British suffragettes in 1913. Photo: AKG / East NewsPolish suffragettes weren't imprisoned or beaten, as their British counterparts were, but their slogans were treated with aversion and derision by many. The press printed damning caricatures and comments about them, criticising their commitment to ‘trivial matters’ while Poland was under occupation. ‘Does a woman stand outside her nation?’ retorted Dulębianka.

Rosa Luxemburg during a speech in Stuttgart, 1907. Photo: East News

Rosa Luxemburg during a speech in Stuttgart, 1907. Photo: East NewsSometimes, this left-wing movement sabotaged its own actions. In her book Damy, Rycerze i Feministki (Damsels, Knights and Feminists), Sławomira Walczewska wrote that ‘socialists would offer words of support to suffragettes during their rallies, but at the same time, they forbid their members from taking part in suffragettes' meetings’.

Born in Zamość, Rosa Luxemburg wrote that bourgeois women who ‘savour the ready fruits of class domination’ add ‘a burlesque trait’ to the suffragette movement. In her opinion, women's emancipation had to go hand-in-hand with social revolution:

Text

Proletarian women, the poorest of the poor, the most deprived of those who have no rights at all: come fight for the liberation of women and humankind from the atrocities of capitalist domination.

The women’s movement declared itself as apolitical, but it was unable to overcome social divisions. Attempts to establish co-operation between Polish and Jewish or Ukrainian activists often fell apart due to nationalist antagonisms. This situation continued even after Poland regained independence.

It is impossible to write about the women’s movement in the 20th century without mentioning Paulina Kuczalska-Reinschmit, the founder of the Związek Równouprawnienia Kobiet Polskich (Polish Women’s Equality Association) and the editor-in-chief of Ster (Helm).

Ster was intended as a platform for exchanging information between suffragettes scattered across the three annexed territories. It published not only humorous texts, but literary pieces by Orzeszkowa, Konopnicka and Żeromski. Through a regular column by Ludwika Ćwierczakiewiczowa – a popular period author of cookbooks and guides for housewives – the journal attempted to attract a wider readership.

Strongwomen

Members of the Lublin ‘Światło’ (‘Light’) Society for the Promotion of Education from Nałęczów: Faustyna Morzycka, Stefan Żeromski, Gustaw Daniłowski, Przemysław Rudzki, Helena Dulęba, Kazimierz Dulęba and Felicja Sulkowska, 1906; photo: Polona

Members of the Lublin ‘Światło’ (‘Light’) Society for the Promotion of Education from Nałęczów: Faustyna Morzycka, Stefan Żeromski, Gustaw Daniłowski, Przemysław Rudzki, Helena Dulęba, Kazimierz Dulęba and Felicja Sulkowska, 1906; photo: Polona

Most suffragettes were engaged in educational activities, especially those excluded from or deprived of access to formal schooling. Initiatives such as reading rooms for women – many of them illegal – were established, such as ‘Flying Universities’ and ‘Kobiece Koła Oświaty Ludowej’ (‘Community Educational Circles for Women’).

Important figures included Faustyna Morzycka, an organiser of educational groups and a fighter in the PPS Underground-Combat Organisation – who inspired the Polish writer Stefan Żeromski to write the story Siłaczka (The Strongwoman). There was also Filipina Płaskowicka, the founder of the Koło Gospodyń Wiejskich (Association of Rural Women), and Stefania Sempołowska, who was said to ‘have taken part in everything that happened in Poland during her 50 years of active life’.

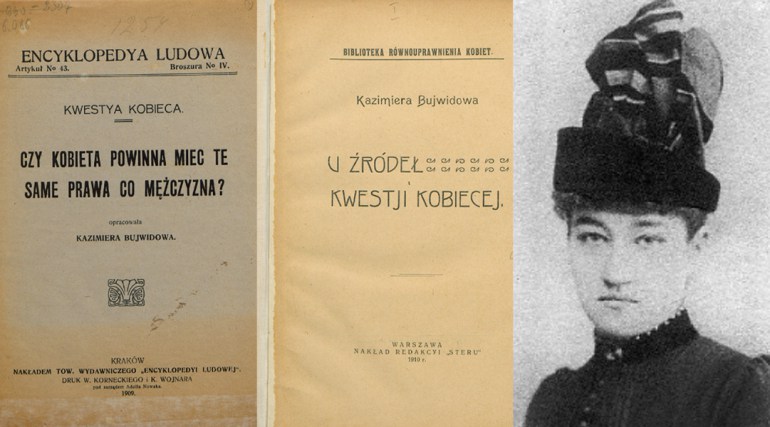

‘U Źródeł Kwestii Kobiecej’ (‘At the Source of Women’s Matters’) by Kazimiera Bujwidowa, 1910, Kraków; ‘Czy Kobieta Powinna Mieć Te Same Prawa Co Mężczyzna?’ (‘Should Women Have the Same Rights as Men?’), 1909, Kraków; and a portrait of Kazimiera Bujwidowa; photos: Polona

‘U Źródeł Kwestii Kobiecej’ (‘At the Source of Women’s Matters’) by Kazimiera Bujwidowa, 1910, Kraków; ‘Czy Kobieta Powinna Mieć Te Same Prawa Co Mężczyzna?’ (‘Should Women Have the Same Rights as Men?’), 1909, Kraków; and a portrait of Kazimiera Bujwidowa; photos: Polona

Kazimiera Bujwidowa, the founder of the first junior school for girls on Polish lands, was tireless in her fight for women’s equal access to education. In her school, students could take an exam that was the first step in applying for university, something as-of-yet unheard for women. She also initiated a campaign for women to apply to Jagiellonian University, which resulted in the institution’s acceptance of its first-ever female students in the year 1897.

The cause for workers’ rights was another important one raised by the Polish suffragettes. The disproportion in wages between the sexes was significant, and women were often sacked when they got married or became pregnant.

Human trafficking was another social problem. In towns and villages in Central-Eastern Europe, many crooks deceived underprivileged women by offering them lucrative jobs, only to put them in brothels. Activists fought this practice by organising missions at train stations, where they engaged female arrivals seeking work and provided them with accommodation and aid in finding a job.

‘We want a complete life!’

A performance of ‘House of Women’ by Zofia Nałkowska at the Polski Theatre in Warsaw, 1930: Maria Przybyłko-Potocka, Zofia Nałkowska, Stanisława Słubicka, Wanda Barszczewska, and Honorata Leszczyńska. Standing from the left: Karolina Lubieńska, Wanda Siemaszkowa, Mila Kamińska and Janina Muncklingrowa; photo: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

A performance of ‘House of Women’ by Zofia Nałkowska at the Polski Theatre in Warsaw, 1930: Maria Przybyłko-Potocka, Zofia Nałkowska, Stanisława Słubicka, Wanda Barszczewska, and Honorata Leszczyńska. Standing from the left: Karolina Lubieńska, Wanda Siemaszkowa, Mila Kamińska and Janina Muncklingrowa; photo: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

For the younger feminist generation – which, to paraphrase Zofia Nałkowska, already knew that they had ‘the right to have rights’ – it was about more than just having the right to vote or access to education. The goal was to change rigid and hypocritical customs. In her 1904 article Cnota Kobieca (‘Woman's Virtue’), Izabela Moszczeńska wrote:

Text

Giving women the right to establish and break off romantic relationships, without limits, with no scruples and no qualms, lies far beyond the borders of the current worldview (…) This kind of morality lowers women to the role of a purchased and well-protected cow.

Delving into such bold topics of morality during this period was considered scandalous, of course, in public opinion – but it also divided the feminist community. At the Polish Women’s Meeting in 1907, a speech by Nałkowska, Uwagi o Etycznych Zadaniach Ruchu Kobiecego (‘Observations on the Ethical Tasks of the Women’s Movement’), ended in great scandal. There was an attempt to disrupt the reading, and Konopnicka and Dulębianka left the room in outrage. Nałkowska’s speech included the following:

Text

Our aim is to thoroughly re-evaluate today’s governing ethics. The division of women into either moral or immoral is based on a male point of view. Our liberation has to give us a new criterion of classification, a new ethical census. Neither our erotic qualities nor our attitude toward men should dictate our morality.

The writer finished her speech with the renowned sentence: ‘We want a complete life!’

Nałkowska wrote in her diary:

Text

A man can know the fullness of life, because he lives as a man and as a human being. But for a woman, there is only a fraction of life – she has to be either a woman or a human being.

It’s possible similar conclusions influenced Nałkowska’s rival, the Young Poland poet Maria Komornicka, to dramatically change her identity. In 1907, she publicly burnt her outfit, put on men’s clothes and began to introduce herself as Piotr Odmieniec Włast. Thinking she had gone mad, her family had her committed to a psychiatric institution.

Becoming citizens

Aleksandra Piłsudska, 1930, photo: Polona

Aleksandra Piłsudska, 1930, photo: PolonaIn 1903, Paulina Kuczalska-Reinschmit wrote:

Text

Throughout history, all the periods when societies flourished or had serious turmoil brought women to light. A passive slave who always takes part in the momentary upheaval but, once the peaceful era returns, is again left in the shadows of the home – her reward for joint achievements.

With the country on the brink of independence, legislating for equality between the sexes was far from a prominent concern. The first draft of the constitution in 1917 did not consider the women’s cause at all. Marshal Józef Piłsudski, soon to be Poland’s chief of state, was unconvinced, as he thought that women were reserved by nature and susceptible to manipulation.

On 28th November 1918, however, a group of suffragettes gathered outside Piłsudski’s villa in the Mokotów district of Warsaw. The umbrellas they used to bang on his windows would soon became a symbol of the movement. The marshal kept them waiting for several hours in the freezing cold and rain outside, but ultimately, he gave in.

One of the reasons for Piłsudski’s capitulation was most certainly Aleksandra Piłsudska, his wife at the time, who was also a feminist activist. The constitution was amended to include women's right to vote in the newly reformed country.

Welcoming Józef Piłsudski at Wiedeński Station upon his visit to Warsaw on 16th December 1916, photo: Piotr Mecik / FORUM

Welcoming Józef Piłsudski at Wiedeński Station upon his visit to Warsaw on 16th December 1916, photo: Piotr Mecik / FORUMAfter this formal declaration on gender equality, many feminist activists branched out to broader social activism – raising education standards, improving conditions for mothers, or campaigning against alcoholism. Others, however, saw it as a symbolic move, rather than a real one, and refused to accept that the fight was over.

‘Gender’ looms over the Second Polish Republic

Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska, photo: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska, photo: Narodowe Archiwum CyfroweAlthough much-discussed in Poland today, the ‘G’ word was rarely heard during the interwar period. That being said, ideological debates back then had plenty of similarities to contemporary disputes. One of the hottest topics was an anti-abortion bill, which recommended punishment of up to five years in prison. Writing in the 1930s, Justyna Budzińska-Tylicka commented:

Text

When a woman does not want to, or cannot give birth; when she shrinks at the thought of giving birth to an unwanted child, one she was forced to give birth to against her will, a child whose arrival could bring a tragic fate to its mother – then this woman is subjected to the old-fashioned, unrealistic and strict male legislation in our penal code that forces her to give birth, that demands forced maternity. A code that shouts in an inhuman voice: Woman, you must give birth!

Two of the other founders of the above-mentioned clinic were Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński and Irena Krzywicka, his long-time partner. Considered one of the biggest scandalisers of the interwar period, Krzywicka proclaimed ‘the twilight of male civilisation’ was nigh and took up taboo issues such as rights for sexual minorities and polyamory.

She battled against abortion being forced underground and demanded guarantees that women receive three days off work during menstruation. Moreover, she had an open relationship with her husband, Jerzy Krzywicki, and did not conceal having an affair with Żeleński, only confirming the opinion of people who declared her as morally corrupt.

In literature, the poem Prawo Nieurodzonych (‘Rights of the Unborn’) by Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska best summed it up in three particular lines:

Text

(…) We do not want grim subterrains,

A father’s curses, a raised axe.

Lullabies made from slaughterhouses and screams!

Irena Krzywicka, 1914, Photo: POLONA

Irena Krzywicka, 1914, Photo: POLONAUltimately, the women discussed here are only a few of the hundreds of Polish women that challenged stereotypes and battled for women’s rights. As the issues they pioneered continue to affect us today, they are all worth remembering, for the past is not only ‘history’ but also ‘herstory’.

British suffragettes, 1910, photo: East News

British suffragettes, 1910, photo: East News

Originally written in Polish by Patryk Zakrzewski; translated by ND; edited by AZ, Aug 2015

Sources: 'Nasze Bojownice' by Cecylia Walewska (Warsaw 1935); 'Szlaki Kobiet: Przewodniczka po Polsce Emancypantek' edited by Ewa Furgał (Kraków 2015), www.herstorie.pl, www.feminoteka.pl/muzeum, www.kobietynawsi.pl

Tytuł (nagłówek do zdjęcia)

[{"nid":"5688","uuid":"6aa9e079-0240-4dcb-9929-0d1cf55e03a5","type":"article","langcode":"en","field_event_date":"","title":"Challenges for Polish Prose in the Nineties","field_introduction":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary\r\n","field_summary":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary","topics_data":"a:2:{i:0;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259609\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:26:\u0022#language \u0026amp; literature\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:27:\u0022\/topics\/language-literature\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}i:1;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259644\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:8:\u0022#culture\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:14:\u0022\/topic\/culture\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}}","field_cover_display":"default","image_title":"","image_alt":"","image_360_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/360_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ZsoNNVXJ","image_260_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/260_auto_cover\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=pLlgriOu","image_560_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/560_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=0n3ZgoL3","image_860_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/860_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ELffe8-z","image_1160_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/1160_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=XazO3DM5","field_video_media":"","field_media_video_file":"","field_media_video_embed":"","field_gallery_pictures":"","field_duration":"","cover_height":"991","cover_width":"1000","cover_ratio_percent":"99.1","path":"en\/node\/5688","path_node":"\/en\/node\/5688"}]