Poland Didn't Always Speak Polish: The Lost Linguistic Diversity of Europe

Throughout the centuries, Poland has been populated by diverse ethnic and linguistic groups, all of which have left their mark. Here's a look at some of the languages spoken in these lands – and a short manual to linguistic idiosyncrasies which have often entailed complicated issues of social and even economic background.

The historical distribution of languages and nations in Central and Eastern Europe reveals many surprises (some of them shown on the map below). These are less perplexing when one considers that most of the lands shown were once part of a multi-ethnic state called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

This tradition of multiculturalism continued after and despite the fact that the state ceased to exist in the late 18th century. The cultural spaces continued to flourish in the 19th century, criss-crossing the official political borders and often overlapping. This amazing linguistic and cultural diversity ceased to exist with the outbreak of World War II.

In the 16thcentury, when Poland was part of a large empire called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, there was an era often called the Golden Age. Polish-speaking nobles (not all of them necessarily Polish – some Lithuanian, Belarusian, and so forth) started to develop a highly peculiar way of speaking which soon became notorious across Europe. Poland at the time had very many fluent and skilled Latin speakers, Latin being widely used as a lingua franca.

This was on one hand due to the fact that Polish nobility had always looked up to ancient Rome, and on the other to the fantastic but widespread belief, stemming from Roman sources, that Polish nobles were descendants of the Sarmatians – an Iranian tribe of the 5th century AD. As a result, knowing Latin was considered an important part of 'Sarmatian' culture. It was also indispensable in the public life of the Commonwealth, with many of the political speeches performed in Latin.

This led to an unexpected slang being born through what is known as 'makaronizowanie' (macaronising): a mixture of Polish and Latin, with Latin heavily influencing Polish sentence structure and word order. This 'macaronic' language was spoken in political gatherings, tribunals, but also in schools and royal courts. Here's an example of such text by one of the most interesting Polish writers of the Baroque period Jan Chryzostom Pasek, who wrote his memoirs at the end of the 17th century:

Text

Ciężki to jest wprawdzie na chorągiew naszę klimakter*, dwóch razem tej matce tak dobrych pozbywać synów; ciężki i nieznośny ojczyźnie paroksyzm*, takich przez niedyskretne fata simul et semel* uronić wojenników, którzy jej periculosissima incendia* hojnie swoją w kożdych okazyjach gasili krwią; przykra całej kompaniej iactura* tak dobrych, poufałych, nikomu nieuprzykrzonych, w kożdej z nieprzyjacielem utarczce podle boku pożądanych i do wytrzymania wszelkich insultów* doświadczonych postradać kawalerów. Ale, ponieważ sama litera święta taką całemu światu podaje paremią*: Metenda est seges, sic iubet necessitas*, dlategoż necessitatem ferre [potius], quam flere decet*, mając prae oculis* konstytucyją* umówionego ante saecula* ziemie z niebem pactum*, że nam tam deklarowano morte renasci*, że nam tam obiecują ad communem* powrócić societatem*. Veniet iterum, qui nos reponat in lucem, dies*.

The words that we have formatted here in bold are Latin loan words, whilst the bold italic fragments are whole Latin phrases. The asterisks mark every place that would require a footnote for contemporary Polish speakers.

The Latin influence on Polish proved very strong – and it took a lot of effort on the part of the linguistic purists of the Enlightenment to rectify it. Today, Polish still stands out among other Slavic languages as the one with biggest load of Latin loan-words.

As to the macaronic language itself, its influence does continue to resonate in contemporary Polish literature. Henryk Sienkiewicz’s Trilogy, one of the most important books in Polish literature, draws heavily on the macaronic language and Sarmatian culture of the 17th century. Surprisingly, it was also the macaronic idiom that served as a major inspiration for one of the best-known Polish books of the 20th century, namely Witold Gombrowicz's Transatlantyk. Gombrowicz often stressed the formative role of Jan Chryzostom Pasek's memoirs and Sienkiewicz for the Polish language.

Picture display

standardowy [760 px]

Vilnius, the modern capital of Lithuania, was until 1939 a multi-ethnic city inhabited by Poles, Jews, Russians, Belarusians and Lithuanians. Postcard from around 1930, photo: Polona.pl

The history of Poland is inseparable from that of Lithuania. Since the 1385 Krewo Union, and especially after the 1569 Lublin Union, Poland and Lithuania together formed one of the biggest countries in Europe, with close to 390,000 square miles (1,000,000 sq km), and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million, in the early 17th century. However, this historical Lithuania was not equivalent to Lithuania today. To put it simply, one could say that this historical Lithuania covered a much wider territory than the present-day country of the same name – and didn't necessarily involve speaking Lithuanian. Here's one example of such an understanding of Lithuania:

Text

Lithuania, my fatherland! You are like health;

How much you must be valued, will only discover

The one who has lost you.

Author

Trans. Katie Busch-Sorensen

Opening title pages of 'Pan Tadeusz' by Adam Mickiewicz, 1834 Paris edition, photo: Polona National LibraryIn these first lines of the Polish national epic Pan Tadeusz – known by heart by virtually all schoolchildren in Poland – Adam Mickiewicz speaks of Lithuania in a sense that is essentially unrelated to modern-day Lithuania. The latter is a Baltic country which gained independence after the fall of the Soviet Union, and which is populated by a majority of ethnic Lithuanians, all of whom speak the Lithuanian language. Lithuania in the days of Mickiewicz was a wide territory that spread over much of Belarus, Poland and Ukraine, and it was populated by Poles, Belarusians, and Jews as well as Lithuanians.

In this historical sense, Mickiewicz was undoubtedly Lithuanian. There are several other cases of prominent ethnic Poles (among them famous figures like Józef Piłsudski or Czesław Miłosz) proudly calling themselves Lithuanians.

For centuries, the Lithuanian language was spoken primarily in the countryside, while much of the local nobility was Polonised. This began to change in the 19th century when a sense of national identity began to grow. This also entailed new interest in the Lithuanian language, an Indo-European language from the Baltic language group – one of the most ancient languages on the continent, bearing many similarities to languages like Latin or Sanskrit.

Interestingly enough, many early Lithuanian artists and writers in the early stage of this Lithuanian national revival – such as Antanas Klementas, Silvestras Valiunas, Simonas Stanevicius, Antanas Strazdas – were essentially creating a bilingual oeuvre, writing both in Polish and Lithuanian. The Lithuanian historian Aleksandravicius Egidijus says that in this first stage of Lithuanian national revival, Lithuanian literature was consistently written in Polish and Lithuanian.

Additionally, some Polish writers of the area didn’t speak a word of Lithuanian and yet can still be considered Lithuanian patriots. Teodor Narbutt – the author of the first ancient history of the Lithuanian people, which spans nine volumes – is one such example. Although the book was written in Polish, it had a significant impact on the Lithuanian intelligentsia, and Narbutt considered Lithuania his only motherland.

Jan Czeczot, photo: WikipediaThe idiosyncrasies of the Central and Eastern European linguistic mash-up include situations where one cannot determine what is the nationality of a given writer. This is often the case not only with the Lithuanian-Polish conundrum, but also in the Polish-Belarusian situation. Several 19th-century writers, like Jan Czeczot or Wincenty Dunin-Marcinkiewicz, wrote both in Polish and Belarusian.

Jan Czeczot (Belarusian: Ян Чачот) is generally considered one of the earliest ethnographers of modern Belarusian because of his endeavours to revive the language after its collapse in the late 17th century. Before that, Old Belarusian (more commonly called Ruthenian) was a language of administration in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and one of the first languages to have its own translation of the Bible (translated by Franciszek Skaryna in 1517). Czeczot is known to have written a collection of Belarusian folk songs, which also included a little Polish-Belarusian glossary. It was first published in Vilnius in 1836.

Cover & title page of 'Poems by Adam Mickiewicz: Volume One', 2nd edition, 1822, photo: Polona National LibraryBut Czeczot's interest in Belarusian folk culture was even more far-reaching. He was a major influence on Adam Mickiewicz in his formative years prior to the publication of Ballady i Romanse (Ballads and Romances) in 1822, a volume of poetry which revolutionised Polish literature. It has been established that Czeczot influenced Mickiewicz's interest in Belarusian folk culture (they were both natives of the region and had gone to school together) as well as his fondness for literary ballads (Ballady i Romanse is inspired by tales told in the Belarusian countryside).

The case of Czeczot shows that in the field of language and nationality there are no easy answers, and that the truth is far more complex than Polish being the language of nobility or Belarusian that of peasants. In the preface to his book, Czeczot says that he still remembers Belarusian (Krewicki, as he calls it) being spoken by his grandfathers.

Konstanty Kalinowski, source: WikipediaHistorical figures, like one of the leaders of the January Uprising of 1863 and national hero of Belarus Konstanty Kalinowski (blr. Kastuś Kalinoŭski), also defied the language-based stereotypes. Born in Mostowlany (today close to Polish-Belarusian border) Kalinouski was the son of the owner of a small factory, and a ferocious advocate for the abolition of serfdom. He was only 26 when he was executed by the Russian authorities in Vilnius on March 10, 1864. Even at this young age, he had already published the first Belarusian language newspaper, Muzhytskaya Prauda, and his only existing poem (written in Belarusian, just like his Letters from under the Gallow) suggests he was a gifted poet. Under the gallows, when referred to as a member of the nobility, the 26-year old Kalinouski famously shouted to the official: "There is no nobility. We are all equal!"

St Andrew's Church in Kyiv, 1875, photo: Polona National LibraryThe linguistic situation in Ukraine allows for no such stories of brotherhood. Modern Ukrainian literature was brought to its current shape by a single man: the poet Taras Shevchenko, who to this day remains an example of acute social awareness. This is especially striking when one compares his work with that of the contemporary Polish Romantic poets, like Mickiewicz and Słowacki. Whereas they seem preoccupied with national issues, and with developing mystical ideologies like Messianism, Shevchenko consistently adopted a socioeconomic perspective.

According to Shevchenko, Ukrainian was the language of the peasants oppressed by the landowners (who also de facto owned people). Shevchenko was born in 1814 in Central Ukraine near Kiev, and of the 47 years of his life, he was free for only nine. This is in marked contrast with the Polish poets of the period, who were all part of the nobility. In his poetry, Shevchenko staunchly encouraged his compatriots to revolt against class oppression – his patriotism was deeply rooted in the social strife caused by the inhumane system of slavery.

It took many years for this perspective to be embraced by readers. For example, the class perspective adopted by Shevchenko in one his most famous poems, Haydamaky – invoking the gloomy days of the Koliyivshchyna, a peasant (Kossack) uprising of 1768 against their Polish masters and Jewish owners – is unparalleled in Polish literature. Shevchenko, with the might of his voice full of humiliation and despair, but also wrath and indignation, remains one of the most important voices of European poetry today.

'Mendele Moykher Sforim (zayn lebn un verk)', published by Sikora & Mylner, 1928, Warsaw, photo: Polona National LibraryThe 19th century also saw the rise of another, even more interregional language. Yiddish – which is basically a Germanic language, with much of the vocabulary influenced by Eastern European Slavic languages as well as Hebrew (and written in Hebrew script) – had been spoken in these lands since the 12th century, when Jews began to migrate from Germany. Considered a folk language, Yiddish had long been denied the role of a medium capable of literary expression.

In the 19th century, however, the lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth became the birthplace of modern Yiddish literature. Amongst its founding fathers were Mendele Moykher Sforim (born in 1835 in Kopyl, today central Belarus), Sholem Aleichem (born in 1859 in Pereyaslav, today Ukraine), and Yitskhok Leybush Peretz (born in 1851 in Zamość, today eastern Poland). All of them were born into what was then the Russian Empire, and what is sometimes today described as 'Yiddishland'.

This impressive Yiddish literature movement reached its apex in Interwar Poland, when Warsaw became the most important Jewish cultural centre in the world. At that point, approximately 80% of Polish Jews spoke and read in Yiddish. Jewish cultural life in Warsaw was booming: Yiddish press (dailies like Der Moment, magazines like Literarishe Bleter or Globus), bookstores, theatres, avant-garde literature (the group Chaliastre was formed in Warsaw in 1922 by Uri Zwi Grinberg, Melekh Ravitsh and Peretz Markish) and a thriving film industry (with The Dybbuk, among other masterpieces of Polish-Jewish cinema).

Y.L. Peretz, source: WikipediaWarsaw served as home to famous Yiddish writers like Y.L. Peretz or Shalom Ash, as well as I.Y. Singer and his brother, the later Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer. For many of them, Poland was fatherland and Polish remained an important language: I.L. Peretz wrote his first poems in Polish, long before he debuted as a Yiddish writer, and later writers like Maurycy Szymel, Debora Vogel or Rokhl Oyerbakh were equally fluent in both languages.

One of the writers identifying with Poland was Shalom Ash, who is famously quoted as saying that the River Wisła spoke Yiddish to him. He said this in Kazimierz (Yiddish: Kuzmir), an ancient town abounding in reminiscences of Jewish past, the most famous among them being the legend of Esterke, the Jewish lover of the Polish King Kazimierz. Ash's dictum was later immortalized by the Yiddish author Shmuel Leyb Shneiderman in his book about his childhood in Kazimierz, entitled Ven di Vaysl Hot Geredt Yidish (When the River Wisła Spoke Yiddish).

Picture display

standardowy [760 px]

Kazimierz painted by Menashe Seidenbeutel; source: Jewish Historical Institute (available at Centralna Baza Judaików)

The flourishing Yiddish culture in Poland came to a sudden halt with the outbreak of World War II and was almost completely destroyed during the Holocaust. Yiddish did, however, survive in Poland after WWII, with Yiddish writers such as Kalman Segal or Hadasa Rubin and Yiddish press (such as Folks-shtime). The last blow to the Jewish and Yiddish presence in Poland was dealt in 1968 during Communist repressions, which led to tens of thousands Jews leaving the country.

This video shows Isaac Bashevis Singer speaking Warsaw Yiddish in his Nobel Prize speech.

Yiddishland can be also considered the birthplace of Modern Hebrew literature, as the earliest speakers of Modern Hebrew often had Yiddish as their native language. Many of the early exponents of modern Hebrew literature were fluent both in Hebrew and Yiddish, like Uri Zwi Grinberg, the Nobel prize winner Shmuel Yosef Agnon or Chaim Nachman Bialik, recognized as Israel's national poet.

A display at Centrum Esperanto, Białystok, photo: Agnieszka Sadowska / AGIt is perhaps because Poland was so multilingual that it gave birth to the best known artificial language. Its creator, Ludwik Zamenhof, was born in Białystok in 1859 to a Jewish family – his first language was probably Yiddish, and later in life, he spoke mostly in Russian and Polish. Białystok was at that time part of the Russian Empire, and was therefore an increasingly multicultural city with Russian, Yiddish, Polish as well as German spoken in the streets. As a boy, Ludwik fantasized about a new, universal language that would end quarrels between nations – he even wrote a little drama in this topic, appropriately entitled The Tower of Babel: Tragedy of Białystok.

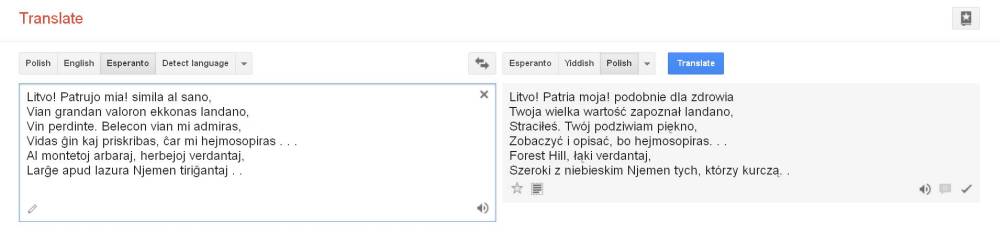

Later in life, Zamenhof managed to develop such a language. The first Esperanto handbook, Unua Libro, was published in Warsaw on 26th July 1887. Esperanto uses word roots taken from many different, mostly Western European, languages. To this day, it is considered one of the easiest artificial languages to learn, and present estimates of Esperanto speakers range from 100,000 to 2,000,000 active or fluent speakers worldwide. Since 2012, Esperanto has also been one of the languages available in Google Translate.

Written by Mikołaj Gliński, Mar 2014

[{"nid":"5688","uuid":"6aa9e079-0240-4dcb-9929-0d1cf55e03a5","type":"article","langcode":"en","field_event_date":"","title":"Challenges for Polish Prose in the Nineties","field_introduction":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary\r\n","field_summary":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary","topics_data":"a:2:{i:0;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259609\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:26:\u0022#language \u0026amp; literature\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:27:\u0022\/topics\/language-literature\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}i:1;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259644\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:8:\u0022#culture\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:14:\u0022\/topic\/culture\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}}","field_cover_display":"default","image_title":"","image_alt":"","image_360_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/360_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ZsoNNVXJ","image_260_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/260_auto_cover\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=pLlgriOu","image_560_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/560_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=0n3ZgoL3","image_860_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/860_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ELffe8-z","image_1160_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/1160_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=XazO3DM5","field_video_media":"","field_media_video_file":"","field_media_video_embed":"","field_gallery_pictures":"","field_duration":"","cover_height":"991","cover_width":"1000","cover_ratio_percent":"99.1","path":"en\/node\/5688","path_node":"\/en\/node\/5688"}]