Trylogia / Trilogy

Still form the Deluge directed by Jerzy Hoffman, 1974, picturing Daniel Olbrychski and Arkadiusz Bazak., photo: Filmoteka Narodowa/www.fototeka.fn.org.pl

Still form the Deluge directed by Jerzy Hoffman, 1974, picturing Daniel Olbrychski and Arkadiusz Bazak., photo: Filmoteka Narodowa/www.fototeka.fn.org.plSienkiewicz’s masterful narratives, rich language and superb endings earned him a solid place in Polish short-story writing, and numerous translations ensured him international recognition. Yet it was his historical novels that elevated him to the peaks of fame, especially Ogniem i Mieczem (With Fire and Sword), Potop (The Deluge) and Pan Wołodyjowski (Sir Michael), the Trilogy he had published in instalments in Słowo between 1883-86.

Sienkiewicz highly rated the historical novel for its didactic and ideological values, and for its contribution to encouraging patriotism and nurturing tradition. He conducted detailed research into the era in which his novels were to be set, inspired by a ‘passionate reading of the age’s chronicles and diaries which aroused more artistic emotion in me than did other ages’. His main focus was the years 1648-73, the time when the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania faced a number of threats, yet overcame them successfully.

Sienkiewicz’s Commonwealth was not free of vices such as egoism, avarice, anarchy and treason. However, when the country was in danger, the knights and noblemen proved able to make huge sacrifices to save the day. In Ogniem i Mieczem, they push back the rebellious Cossacks led by Chmielnicki, and in Potop, they stop the Swedish invasion, while in Pan Wołodyjowski, they triumph over the Tartar hordes.

Still from Pan Wołodyjowski directed by Jerzy Hoffman, 1969, picturing Tadeusz Łomnicki and Jan Nowicki, photo: Filmoteka Narodowa/www.fototeka.fn.org.p

Still from Pan Wołodyjowski directed by Jerzy Hoffman, 1969, picturing Tadeusz Łomnicki and Jan Nowicki, photo: Filmoteka Narodowa/www.fototeka.fn.org.pSienkiewicz combines the adventure novel with the historical love story, setting the action in the huge territory from Silesia to easternmost Ukraine, mostly in military camps, but also at the royal court, in the manors of the nobility, and in local parliaments. The plot is extremely dynamic, with lots of skirmishes, pursuits, escapes and abductions. In each book, at least one spectacular battle is fought in a besieged castle: in Zbaraż in Ogniem i Mieczem, Czestochowa in Potop, Kamieniec Podolski in Pan Wołodyjowski. The superbly evocative descriptions of battles, skirmishes and executions are not free of cruelty.

Sienkiewicz populated the pages of his Trilogy with a range of characters, including historical persons such as Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, Stefan Czarnecki, Paweł Sapieha, kings Jan Kazimierz and Jan Sobieski, Karol Gustaw and Bohdan Chmielnicki as well as fictitious characters, notably the protagonists of each part, i.e. Skrzetuski, Kmicic and Wołodyjowski. As one would expect of an adventure story, the characters are usually good or bad, their morality clearly defined. Yes, Kmicic does sin when young, but redeems himself with heroic actions, and Mr Zagłoba, the colourful Sarmatian, liar, boozer and coward, does great things at critical moments.

Historical events are invariably intertwined with love affairs: between Skrzetuski and Helena Kuncewiczówna, Kmicic and Olenka Billewiczówna, and Wołodyjowski and Basia Jeziorkowska. These love affairs are not without obstacles, for each maiden is also loved by a bad character and traitor (Bohun, Bogusław Radziwiłł, Azja Tuhajbejowicz), and then kidnapped and held prisoner. Naturally enough, at the end, the positive hero prevails and marries his beloved. Thus valour and patriotism triumph in public life, while love and family are victorious in private lives.

Still from With Fire and Sword directed by Jerzy Hoffman, photo: promotional materials

Still from With Fire and Sword directed by Jerzy Hoffman, photo: promotional materialsThe Trilogy reveals Sienkiewicz’s enormous writing talent: the ability to develop the plot, diversify the characters, provide descriptions, convey period detail and style in an appropriately archaic language. While he was not terribly modest – indeed, he thought highly of his writing skills – the popularity of the three novels exceeded even his own expectations. Initially an author of adventure and historical novels with patriotic messages, writing for the cause as well as for the money, he became a national icon as a writer writing to raise the spirits. He accepted this role with dignity and solemnity. His attractiveness to readers was also confirmed beyond his own country, the trilogy having been translated into more than twenty languages. All three books have been filmed, and Ogniem i Mieczem was adapted for the stage and performed at Sara Bernhard’s theatre in 1904.

Krzyżacy / The Teutonic Knights

A similar combination of a knight’s adventures and a romance can be found in Sienkiewicz’s next novel, Krzyżacy (The Teutonic Knights), published in Tygodnik Ilustrowany between 1897-1900. The story develops at the royal court and manors, in monasteries and on the roads, in a primeval forest and at the Teutonic castle in Szczytno. The historical characters include, among others, King Jagiełło / Yogaila and Queen Jadwiga, while the main character is Zbyszko from Bogdaniec, a young, hot-headed knight. The story is set against the historical background of the escalating conflict with the Teutonic Order, an arrogant and greedy organisation which justifies any crime in the name of Christ.

Still from The Teutonic Knights directed by Aleksander Ford, 1960, picturing Ryszard Ronczewski, photo: Polflim / East News

Still from The Teutonic Knights directed by Aleksander Ford, 1960, picturing Ryszard Ronczewski, photo: Polflim / East NewsThe romantic theme is provided by Zbyszko’s love of Danusia, the daughter of Jurand of Spychowo and the lady-in-waiting of the Duchess Anna Mazowiecka. In the wake of the conflict with Jurand, the Teutonic Knights kidnap Danusia. Jurand follows his daughter, but the knights grab and maim him. Danusia falls ill and loses her senses in captivity. When finally free, she dies in Zbyszko’s arms. After a period of despair, Zbyszko finds happiness with Jagna, his childhood friend. The historical conflict ends with an epic description of the Battle of Grunwald, a military success for Polish and Lithuanian knights. The dark tones used by Sienkiewicz to depict the Teutonic Order reiterated what he had voiced a number of times before, namely his protest against the policies of Prussia, considered by him to be the heir of the Order’s imperial expansion.

Quo Vadis

Sienkiewicz’s greatest success – the Nobel Prize (1905) – came with Quo Vadis. Published in Gazeta Polska between 1895-96, this novel shows Rome at the time of Nero’s rule, with all its splendour, sybaritism and intellectual culture. This pagan world is witness to the secret and quiet birth of a new, Christian world. Winicjusz, a young patrician, loves Ligia, a beautiful Christian captive of Slavic descent. His love is not requited until he becomes convinced of the moral strength of the new religion and its repressed followers.

Still from Quo Vadis directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz, photo: promotional materials

Still from Quo Vadis directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz, photo: promotional materialsSienkiewicz, who was familiar with Rome, both in ancient and modern times, paints a colourful and captivating vision of the emperor’s court and of such characters like Nero, Petronius the poet and Seneca the philosopher. The first Christians, in contrast, are morally strong, but artistically weak. Despite that, the Christian values earned the author the Nobel Prize. The novel was translated into more than forty languages and proved perfect material for an opera (Jean Nouges, 1909), several films, an oratorium (Feliks Nowowiejski) and a panorama (Jan Styka).

W pustyni i w puszczy / In Desert and Wilderness

Still from In Desert and Wilderness, 1973, directed by Władysław Ślesicki, picturing Monika Rosca and Tomasz Mędrzak, photo: Studio Filmowe Kadr / Filmoteka Narodowa/www.fototeka.fn.org.pl

Still from In Desert and Wilderness, 1973, directed by Władysław Ślesicki, picturing Monika Rosca and Tomasz Mędrzak, photo: Studio Filmowe Kadr / Filmoteka Narodowa/www.fototeka.fn.org.pl Another popular novel by Sienkiewicz was W Pustyni i w Puszczy (In Desert and Wilderness), a book for young readers. Printed in Kurier Warszawski in 1910-11, it drew on Sienkiewicz’s experiences during his African trip. The plot is set in Sudan during the Moslem uprising against the English. The supporters of Mahdi, the leader of the uprising, abduct the children of a Pole and an Englishman working for the Suez Canal Company. The children, Staś Tarkowski and Nel Robinson, escape across much of the African continent, experiencing a number of adventures. Staś fights with wild animals, searches for food, saves an elephant trapped in a gorge, and cures Nel of malaria. The children are accompanied by Saba the dog and later joined by the saved elephant and a couple of young blacks, Kali and Mea. Finally, they return to their fathers and the brave Staś, a Polish patriot, makes an inscription Long live Poland! on Kilimanjaro.

Bez dogmatu / Without Dogma and Rodzina Połanieckich / Children of the Soil

Henryk Sienkiewicz with his sister Jadwiga Korniłowicz, photo: Topham Picturepoint / Forum

Henryk Sienkiewicz with his sister Jadwiga Korniłowicz, photo: Topham Picturepoint / ForumAfter the Trilogy, Sienkiewicz published two contemporary novels, Bez Dogmatu (Without Dogma) and Rodzina Połanieckich (Children of the Soil). Interestingly, both novels were not quite received the way the writer had intended. The first one is a diary kept by the thirty-five-year-old, Leon Płoszowski, a wealthy count living in Rome with his father. A patron of European salons, comprehensively educated, sensitive to beauty, and a women’s favourite, he suffers from an illness of will and emotions. Seeing neither the purpose nor the sense of life, he is unable to find grounds for religious faith or a stable system of values. Contemporary science and philosophy, as well as his own over-sensitivity and introspection, have turned him into a sceptic. This does not make him happy, but he cannot find a cure, especially as his comfortable lifestyle does not motivate him to make an effort. An aunt who settles in Płoszów encourages him to marry Aniela. He falls in love, yet cannot decide to marry her, instead procrastinating, withdrawing, and getting involved in love affairs. Finally, for practical reasons, Aniela marries Kronicki, a shady businessman. Płoszowski’s love for her turns into an obsession, his emotions moving from love to hate to contempt and back to love. He tries to get Aniela back, but she responds with a ‘catechism simplicity’. The story ends tragically for both of them: after her husband’s suicide, Aniela, expecting a baby, dies, and Płoszowski’s last entry in his diary talks about taking his life.

This psychological drama contains Sienkiewicz’s diagnosis that society is sick. There is the privileged elite on one hand and a completely uncivilized crowd on the other, with a void between that will hopefully be filled by such characters as the Chrostowski brothers, the sons of the Płoszów farm manager, who have healthy bodies and minds, and are vigorous and enterprising.

Sienkiewicz was hard on his protagonist: This novel is intended as, and will be a clear warning of, what a life without dogma leads to – a mind which is sceptical, over-refined, deprived of simplicity and lacking in support’. The generation of modernists, however, found him a positive hero, decadent suffering from la malaise du siecle, an over-sensitive, doomed man, who is nevertheless a harbinger of spiritual evolution. The novel was fashionable and popular and, translated into eighteen languages, aroused considerable interest, most notably from Leo Tolstoy.

The protagonist of Rodzina Połanieckich, is, in turn, an impoverished nobleman doing business in Warsaw. He marries Marynia, a noblewoman deprived of her property. Marynia, who gets married out of necessity, follows her moral code in being a good and faithful wife. Her husband, however, follows a different code of morality. He is tough and ruthless in business and cheats on his wife. The end is quite unexpected and fairytale-like: Połaniecki buys back his wife’s property and returns to their roots, to the land and family values. Naturally, the critics opined that Sienkiewicz regarded him as a positive character and an exponent of his own views.

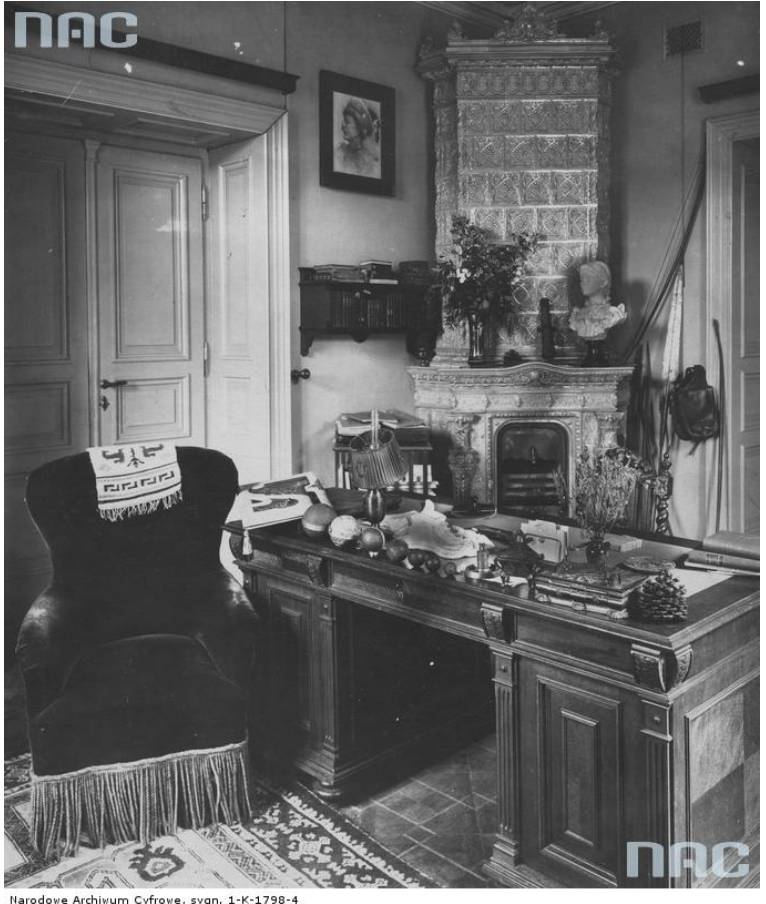

Henryk Sienkiewicz’s study in Warsaw, photo: NAC

Henryk Sienkiewicz’s study in Warsaw, photo: NACWiry

In 1909, Głos Warszawski printed Wiry, a rather unsuccessful political novel in which Sienkiewicz expressed his concern about the Russian socialist movement and its potential implications for Poland.

Sienkiewicz and His Critics

It was invariably the Trilogy that attracted the largest readership, making Sienkiewicz a national icon. The masses loved him. In 1900, the nation presented him with a manor in Oblęgorek near Kielce (now housing his museum.) Intellectual elites did not share this enthusiasm, but they dare not attack him. True, Bolesław Prus published some critical notes on Ogniem i Mieczem in 1884, but did so with caution. He expressed his recognition of the artistic merits of the novel, yet deplored the fact that nobody could learn history from it, for the origins and nature of the Cossack rebellion as presented by Sienkiewicz were totally different from historical fact.

Wacław Nałkowski went further in Głos in 1894. In line with his theory of the transformation of biological forces into psychic energy, he announced that a tired writer might sometimes take a break by escaping into mythology. Things are worse, however, if one is driven by egoistical motives and neither wants nor is able to go beyond mythology. Nałkowski found such detrimental national mythology in Sienkiewicz’s writing, and the more popular it was, the more detrimental it became. It is worth noting that the publisher refused to include this text in Nałkowski’s volume of writing Jednostka i Ogół (One and the Mass).

A true debate was sparked off by Sienkiewicz’s appraisal of Młoda Polska (Young Poland’s) literature in Kurier Teatralny in 1903. Sienkiewicz reduced the entire movement, and particularly the writings of Przybyszewski (though he never mentioned his name) to ‘heat and promiscuity’. (Earlier, in 1899, Sienkiewicz had visited Przybyszewski to assess his living conditions and assigned him a grant in the name of his deceased wife of 3,600 crowns). Przybyszewski published the following response in Głos:

The mind boggles at the words used by one writer to denounce another writer’s concentrated and long work, especially one that bore such weighty implications as the powerful awakening of intellectual life in Poland during the past four years...

Despite the differences between them, the positivists and the modernists found common ground when evaluating Sienkiewicz’s writing. It was, as Stanisław Brzozowski put it, his ‘fundamental lack of belief in the profundity and complexity of the world’. Positivists believed Sienkiewicz unable to see the complexity of social processes; modernists found him insensitive to the metaphysical aspect of the world. Both reached the same conclusion: that he promoted easy optimism, intellectual laziness and spiritual deficiency. It became clear that the Sienkiewicz debate was about national culture and its salient values rather than about literature, an argument between the modern Pole and the catholic Pole, the latter an exponent of anachronistic views about the nobility. And while modernity meant different things to a positivist community leader, a socialist, a labour ideologist and an artist pursuing the metaphysical truth, they had one enemy. The essence of the conflict was soon grasped by Głos. Its story, Społeczny Obrachunek (Social Soul-Searching) read:

...it is not an occasional polemics, it is a fundamental argument about the character and the contents of the entire contemporary literature and of our entire spiritual life. (...) Assessing Henryk Sienkiewicz is an exercise in social soul-searching.

The funeral of Henryk Sienkiewicz, 1924, the main train station in Warsaw, photo: NAC

The funeral of Henryk Sienkiewicz, 1924, the main train station in Warsaw, photo: NACStanisław Brzozowski responded to ‘heat and promiscuity’ in an article I Smutek Tego Wszystkiego (And the Sadness of It All), expressing his disappointment with such a great writer failing to understand the reality, the nature of historical processes and social transformations. Nałkowski’s answer in an article Zbyteczny Ból (Useless Pain) was: there is nothing to be sad about, Sienkiewicz never understood the reality nor the nature of the historical process and social transformations, opting instead for a falsified vision of history, of shallow religion and social hypocrisy, his social idol being Połaniecki, ‘the utter swine and hypocritical philistine’. This encouraged Brzozowski to mount more intense attacks in his subsequent pieces: Henryk Sienkiewicz i Jego Stanowisko w Literaturze Polskiej (Henryk Sienkiewicz and His Position in Polish Literature), Współczesna Powieść Polska (Contemporary Polish Novel), Legenda Młodej Polski (The Legend of Young Poland). To Brzozowski, Sienkiewicz was an apologist of the passing world and its out-of-date noble culture that was incompatible with contemporary times, a eulogist of an unproductive, non-historical and unsocial class who tried to convince his readers that this was their spiritual fatherland:

If there is anything I hate with all my soul it is you, the Polish sluggishness, Polish optimism of duds, layabouts, cowards. From the 17th century we have been Europe’s gawkers. ... What has been the essence of mankind’s life – the back-breaking work – is a pastime to us. Sienkiewicz has codified and given an esthetic frame to our position; he is a classic of Polish unawareness, of noble ignorance.

Two epithets which Brzozowski created to evaluate such a vision of the world have made it into everyday language: ‘Polanieckiship’ and ‘gaga Poland’. ‘Polanieckiship’ originated from the gaga dementia of the Polish nobility:

The only thing Sienkiewicz understood from the life of the bourgeoisie was that exploitation enabled good living. ... His Połaniecki is not a successful bourgeois – he is a dull commoner, blind to the rights of others, enamoured of himself. He has transferred the vices of the fallen class to new conditions and has adapted to them...

Nowadays, Sienkiewicz’s works no longer stir up such emotions. His historical novels are read as adventure stories. And although their popularity with the younger generation has decreased, libraries still have waiting lists, and screen adaptations are box-office hits. Nevertheless, the debate goes on between the two positions, that of the traditional catholic Pole upholding the patriarchal family and that of the European Pole, a creative participant in the transformation of society.

Main edition of Sienkiewicz’s works: Dzieła (Works), ed. Julian Krzyżanowski, vols. 1-60, Warsaw 1948-55.

Author: Halina Floryńska-Lalewicz, April 2006, last revised: January 2016, GS