Playing with Censorship: How Polish Artists Dealt with the Communist Regime

The breadth of censorship under the communist regime in post-war Poland was, unsurprisingly, anathema to freedom of speech. But it was not infallible. The first in line to defend self-expression were people from the arts, and their methods were often deliciously inventive.

Censorship is necessary. Censorship is an art. A good censor should be an artist. Besides, it’s a game.

Writers, filmmakers, actors and artists all fiddled with it, often reaching for metaphors to convey secret meanings. It was hardest for the ones who worked with words. Even the Aesopian language they used, had to be read in a very specific way. One cannot presume that the censors, meticulously trained in their field, were deaf and had no self-preservation instinct whatsoever. Every allusion in the arts had to be very skillfully hidden or presented in such an ambiguous form, that the censors could in all probability ‘not notice’ (or at least claim to, if necessary).

If authors tried to reach to their audience through allusions or Aesopian language, censors would try to spot catch it and either banned it from going to print or would change a specific word, thus smudging the actual sense. This was essentially tying artists’ hands, gagging them, so they couldn’t speak the truth.

Many authors managed their way around this. Polish writer Ludwik Jerzy Kern reminisced about the pioneer era of satire in Poland under communist regime when censors were hardly educated at all:

Doing satire in our circumstances wasn’t easy... To save ourselves, we often wrote fables – a literary genre which appears under totalitarian regimes. You replace a human being with an animal in some places, and the censors would let it go. That’s how they did it in antiquity and that’s how we did it back then. In Stalinist times we wrote stories. To be able to publish something saucier, we, the 5 satirists from Kraków – Marian Załucki, Karol Szpalski, Witold Zechenter, Bogdan Brzeziński and I, we used a bit of a diversion. All we had to do was write ‘based on a fable by Malenkov’ or ‘by Charaputkin’ under the story’s title. After all, no self-respecting censor would admit to his lack of knowledge of Charaputkin’s work.

The Khrushchev thaw came and 1954 marked the start of battles over the Students’ Satirical Theatre (Studencki Teatr Satyryczny known as STS), which had just opened. One conflict is described by Jarosław Abramow-Newerly recalls one of the more heated ones:

Once the director of censorship in Warsaw, Rusinov, said to us: ‘Listen up, you’ve got to be aware of the fact that after the October Revolution there was indeed a canvassing of avant-garde theatre, but in the 1930s Meyerhold backed out of it as a result of general criticism...’ ‘What the hell are you talking about? – screamed Drawicz – You know very well that Meyerhold was murdered! Why don’t you quit with the euphemisms and stop showing green meadows, where graves lay, comrade Rusinov! [...] Rusinov was stunned and turned red. We all looked at Drawicz. His attack had succeeded.

In the busy life of the Students’ Satirical Theatre, there were many unexpected surprises. Jan Tadeusz Stanisławski recalls another argument with the censors. The play Mayakovsky is Dead was watched by two censors, who finally summoned their supervisor to watch with them. He watched it with no trace of emotions. In the aforementioned STS. Everything Started Here, we read:

Suddenly the new censorship director stood up and shaking our hands, started saying enthusiatically: ‘A very, very good play. My congratulations! We accept it, of course we accept it!...’ Our faces must have had such stunned expressions as the faces of the two young censors, sitting in the last row. I must confess, we fell in love with the new censorship director. And it was a mutual feeling. ‘I’m a a pre-war communist’ – he used to say – ‘and everything I do, I do seriously. As I was appointed to this position, I will conduct my duties in accordance with my ethics, consciousness and the best interest of the public. Whoever doesn’t like that can remove me from my position. But as long as I’m in it, nobody is going to tell me what to do over the phone.’ [...] That’s what ‘our’ director was like. He told us in advance who was informing on us and who we could talk to if we needed help. He came to the premieres with his daughter, and relaxed, joyful as he was, he told her: ‘Look, darling, these are very wise young people; they know, what’s going on.’ Surely enough, he wasn’t around for long. The party made him look like a madman, an ‘uncommunicative’ person, and made sure he was quickly sent into retirement. But he stayed in our grateful memory for a long time.

The meeting point of culture and censorship sparked dangerously, but there were miracles from time to time. Jarosław Abramow-Newerly recalls an unusual incident:

My first censor at the Students’ Satirical Theatre, Jerzy Kleyny, found his calling and became a satirist. After the events in October, following in our footsteps, he did a cabaret in the censors’ headquarters, which was the most grotesque of all.

Building on 2 Mysia Street, the former censors’ headquarters, photo: W. Kryński / Forum

Building on 2 Mysia Street, the former censors’ headquarters, photo: W. Kryński / ForumSatirist and singer Andrzej Rosiewicz stated, that contrary to what is now said, censors were actually cultured and well-read people. Graduates of Polish Philology or Journalism. The beloved Polish songwriter Wojciech Młynarski had said that his cooperation with the Dudek cabaret was one great school of avoiding the censors.

The poet and satirist Jonasz Kofta used to say that the censors in Poland under the communist regime were most afraid of satire. So he wrote in a metaphorical, but understandable way. He had sarcastically said: ‘I’d also be mad. You think you’re writing very ambitiously and then this simpleton comes and understands everything. It’s insolent!’

Because of the political aspect of their work, satirists were most prone to being censored. Some, like artists from the Salon Niezależnych (editor’s translation: Independents’ Salon), were even harassed by the censors and the authorities. Jacek Kleyff wrote:

We, the Independents’ Salon, wanted to trick the censors, just like the Students’ Satirical Theatre. That meant going along with what they changed, but then singing it exactly they way we wanted to.

The Independents’ Salon were finally banned from performing altogether. And they weren’t the only ones. Jan Poprawa had said:

One can say that this way, through censorship, independent authors were transformed into opposition authors.

The musician and composer Tadeusz Woźniak recalled how in 1968, the censors banned his song To Będzie Syn (editor’s translation: It Will Be A Son), which allegedly ‘stabbed a knife in the backs of Polish soldiers who intervened in Czechoslovakia.’ As if a song could change or influence anything…

The Piwnica Pod Baranami (often translated as the Cellar under the Rams) in Kraków never bothered with the Political Bureau’s commands – they just didn’t send in their texts for censoring, and that is probably the reason why they lasted for so long. From time to time, a censor would appear and Piotr Skrzynecki, head of the Cellar, was dragged to the Culture Department of the Party and they would threaten to close the cabaret. And they really did close it a few times.

This was the case in June 1958, when the Parisian team of Madeleine Renaud and Jean-Louis Barrault arrived in Kraków. They performed at the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre as Célimène and Alceste in Molière’s The Misanthrope. After their performance, they asked to see a cabaret in the Cellar, which was closed by the authorities at the time. A panic broke out, the Party was in a tizzy and ran all around Kraków, searching for Piotr and his crew. All of a sudden the Cellar was acceptable again.

A contact print with the markings by the censor, part the so-called ‘preventative censorship’ of the Interpress Agency, photo: J. Morek / Forum

A contact print with the markings by the censor, part the so-called ‘preventative censorship’ of the Interpress Agency, photo: J. Morek / Forum

Once, during a play during the cabaret’s tourneé in Wrocław, the satirist Wiesław Dymny, delayed his entrance onto the stage, so the rest of the cast started to chant ‘Wiesiu! Wiesiu!’ enticing him to come out. When he finally came out, he couldn’t remember any of his lines, and although everyone was trying to help him out, he ended up not saying a word. All evening he just sat in a rocking chair. That’s what happened.. However, The Wrocław censors were especially cautious. At night, the police dragged the artist straight off the street. The following day, he was charged with insulting comrade Władysław Gomułka (his pseudonym being ‘Wiesław’), who, ignoring the nation calling him ‘Wiesiu! Wiesiu!’, just rocked and rocked it.

Dymny was impressed and thought that the censor’s talent was being wasted in that position and offered him a more suitable job – in the cabaret. Right after the guest shows of the Cellar in the Stodoła club in Warsaw in 1981, Piotr Skrzynecki was summoned by the authorities in charge of cultural affairs. He was to explain the meaning of a set detail – a bust of Lenin in a hanging golden cage with a lit candle in front. The Soviet Embassy took it as a snub. Piotr explained it all to the officers:

We wanted to put a parrot in the cage, but it was too big. So we used the first thing we stumbled upon.

After the death of Piotr Skrzynecki, Marek Pacuła was chosen as his successor in the Cellar. He reminisced about his experience with the censorship changing a sentence in his book:

In my story Za Chlebem (editor’s translation: Looking for Bread) there is a passage: ‘Old Dyzma sat by the house, and it squealed. – What’s that squeal? – Poverty – answered Poverty and left the country, as it knew Old Church Slavonic.’ The last, complex passage was deleted by the overzealous censor and replaced with: ‘as she knew other Slavic languages’. ‘Wonderful – said Marek – We’ll have the entire Comecon’. It was too late for the censor to back out. So the programmes of The Cellar and the Third Polish Radio station used the new and, truthfully better version.

At the beginning of martial law in Kraków, instead of three newspapers, you could get only one, with a vignette of the following titles: Gazeta Krakowska, Dziennik Polski and Echo Krakowa. And it wasn’t particularly popular. The poet and publicist Waldemar Żyszkiewicz wrote about an incident concerning none other than the leader of the People's Republic of Poland General Wojciech Jaruzelski himself:

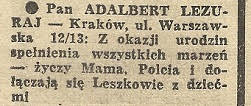

Only once did the Kraków Newspaper disappear from kiosk stands. And in Warsaw, people paid Cracovians up to 100 złoty to get their hands on a copy. It was all because at the beginning of 1983, the editorial board introduced a column entitled ‘Readers’ Wishlist.’ Its life was short but exciting. The 18th March 1983 edition contained the following wishes: ‘Mr. ADALBERT LEZURAJ – Kraków, 12/13 Warszawska Street: the best birthday wishes – from Mom, Polcia and the Leszkowie with their children.’ The newspaper exchanded hands, and soon the entire city was laughing their heads off. The fact that ‘Adalbert’ is the Latin version of the Polish name ‘Wojciech’ soon became universal knowledge...

If you add the last name (read backwards: JARUZEL, Wojciech Jaruzelski's nickname)... Things quickly got heated, and the column soon disappeared.

Although nobody misses censorship, the attempts at restraining it were also unwanted sometimes – and not only by the authorities. Publisher Rafał Skąpski recalls how in the mid-1980s the head of the National Council of Culture, Professor Bogdan Suchodolski, intended to abolish the censorship of poetry. He then commissioned Skąpski to talk to the heads of the main publishing houses of the time: PIW, Czytelnik, Iskry. They were all rather reluctant to agree to the professor’s idea: they would no longer have a polite excuse to avoid printing bad poetry (of which there was a lot). Beforehand, when authors submitted poorly-written and amateurish pieces, publishers would simply tell them ‘in confidence’ that they couldn't print them because of the censors!

Article originally written in Polish, Feb 2016, translated by WF, Mar 2017

Sources:

- Citation from the film Escape from the Liberty Cinema

- Błażej Torański, Knebel. Cenzura w PRL-u, Warsaw 2016

- Paweł Szlachetko, Janusz R. Kowalczyk, STS. Tu wszystko się zaczęło, Warsaw 2014

- Jarosław Abramow-Newerly, Lwy STS-u, Warsaw 2005

- Jacek Kleyff, Rozmowa, Wołowiec 2012

- Jan Poprawa, Na studenckiej estradzie in: Kultura Studencka (zjawisko – twórcy – instytucje) edited by Edward Chudziński, Kraków 2011

- Janusz R. Kowalczyk, Wracając do moich Baranów, Warsaw 2012

- Waldemar Żyszkiewicz, Gadziecho i Lezuraj, 13 December 2013, www.salon24.pl

[{"nid":"5688","uuid":"6aa9e079-0240-4dcb-9929-0d1cf55e03a5","type":"article","langcode":"en","field_event_date":"","title":"Challenges for Polish Prose in the Nineties","field_introduction":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary\r\n","field_summary":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary","topics_data":"a:2:{i:0;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259609\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:26:\u0022#language \u0026amp; literature\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:27:\u0022\/topics\/language-literature\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}i:1;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259644\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:8:\u0022#culture\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:14:\u0022\/topic\/culture\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}}","field_cover_display":"default","image_title":"","image_alt":"","image_360_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/360_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ZsoNNVXJ","image_260_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/260_auto_cover\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=pLlgriOu","image_560_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/560_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=0n3ZgoL3","image_860_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/860_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ELffe8-z","image_1160_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/1160_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=XazO3DM5","field_video_media":"","field_media_video_file":"","field_media_video_embed":"","field_gallery_pictures":"","field_duration":"","cover_height":"991","cover_width":"1000","cover_ratio_percent":"99.1","path":"en\/node\/5688","path_node":"\/en\/node\/5688"}]