Joyful Metal & Furious Rabbits: New Art from Silesia

Since the 1950s, Upper Silesia has been represented by three groups, each more eccentric than its predecessor. Culture.pl examines the path that Polish painting has taken in this region – with a particular focus on today’s generation.

The 1950s

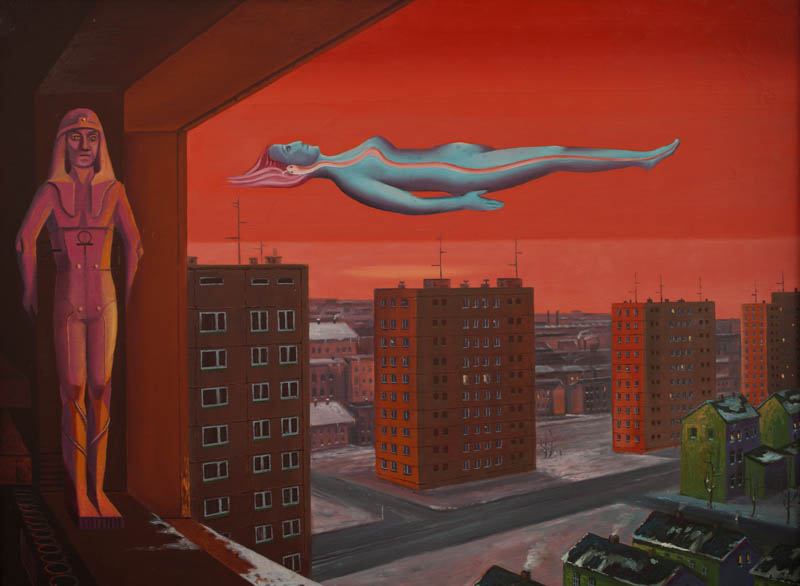

‘Świecące’ (Shining) by Andrzej Urbanowicz, photo: private archive

‘Świecące’ (Shining) by Andrzej Urbanowicz, photo: private archiveDuring the Stalinist era, a group of avant-garde artists (with some architects and art historians) was formed in Katowice, inspired by the Silesian work of Julian Przyboś. Their artistic Bible was Władysław Strzemiński’s Teoria Widzenia (Theory of Vision). Strzemiński died in 1952, followed by Stalin the year after. The St-53 group held its first exhibition several months later. The second half of its name was derived from the date; the first from Katowice itself, renamed Stalinogród by the party authorities.

The late 1960s

‘Medytacje’ (Meditations) by Erwin Sówka, 1986, photo: the Silesian Museum, Katowice

‘Medytacje’ (Meditations) by Erwin Sówka, 1986, photo: the Silesian Museum, KatowiceThe St-53 group broke up in the 1960s, but its collaborators Urszula Broll and her future husband, Andrzej Urbanowicz, set up a workshop in the attic at No.1 Piastowska Street. By the end of the decade, they had been joined by a trio of artists and formed the Oneiron group, representing the esoteric underground – far removed from St-53’s European avant-gardist experiments. Oneiron’s members studied psychoanalysis and esoteric literature, and were fascinated by Eastern religions, Zen, and American counterculture phenomena that emerged from the changes of 1968. No.1 Piastowska Street was a place where communist reality collided with that counterculture, even literally – Allen Ginsberg once visited the city, for instance.

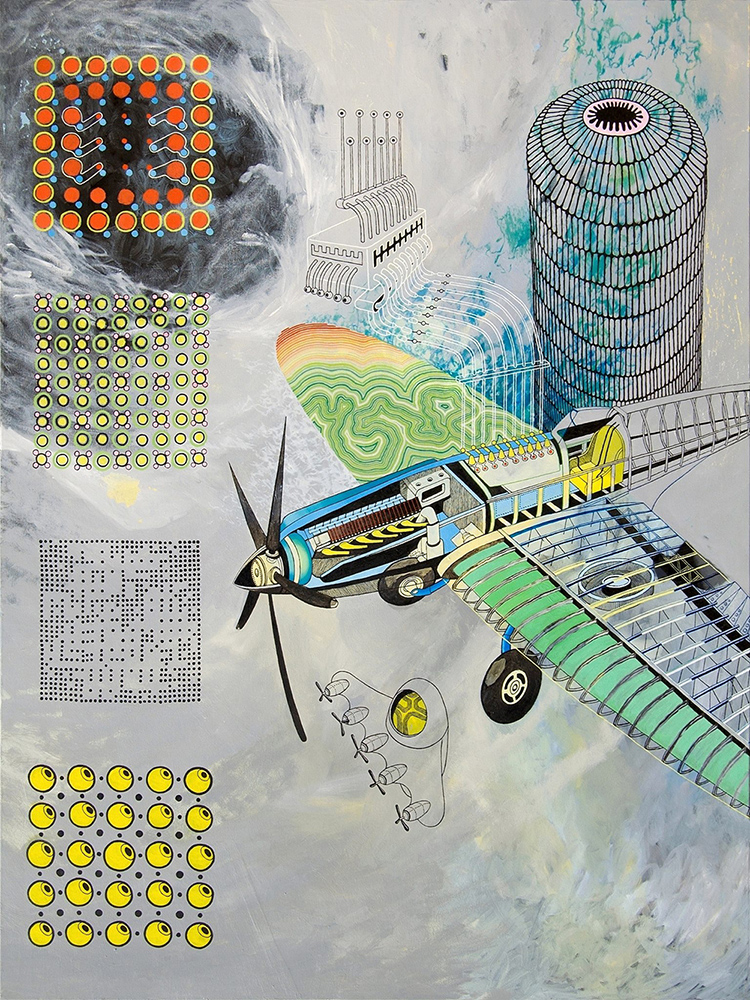

‘Pestycydowy Deszcz nad Kartofliskiem’ (Pesticide Rain over a Potato Field) by Marek Rachwalik, 2015, photo: courtesy of the artist

‘Pestycydowy Deszcz nad Kartofliskiem’ (Pesticide Rain over a Potato Field) by Marek Rachwalik, 2015, photo: courtesy of the artist

Initially, Urbanowicz worked in the style of artists like Jean Dubuffet, who coined the term art brut. Later, he studied the writings of local magic enthusiasts from the turn of the century, which led him towards compositions full of alchemical colours and motifs such as towers, the sun and lotus flowers. Another subcutaneous art brut scene had been developing locally for two decades: an amateur art club – later known as the Janowska Group – formed at the Wieczorek coal mine’s cultural centre. Its members were miners and mine staff who were also increasingly drawn towards esoterica and Oriental mysticism. Erwin Sówka’s paintings combined genre scenes with Catholic spirituality, featuring fantastic and surreal images that bordered on Hindu iconography and sci-fi illustration.

Since the 1990s

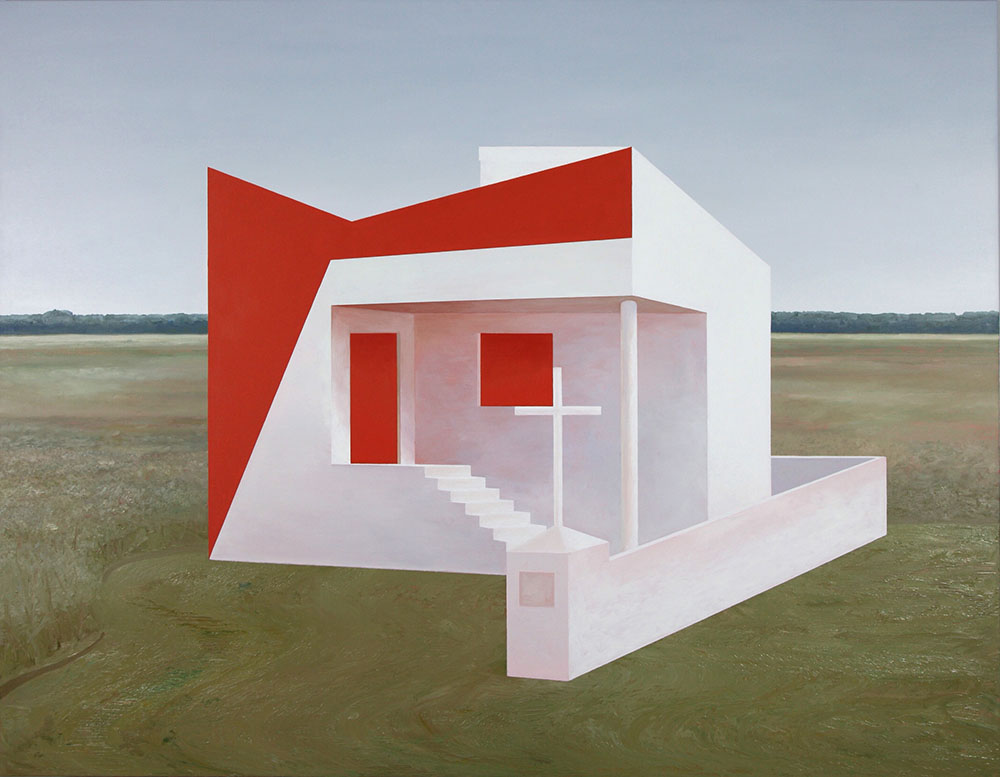

Andrzej Tobis, Rzeźba Dom Polski (Polish House Sculpture), 2014, photo: courtesy of the artist

Andrzej Tobis, Rzeźba Dom Polski (Polish House Sculpture), 2014, photo: courtesy of the artistOver the past two decades, the history of Polish painting – and visual arts in general – has been extremely fragmented. Collaborative activity lost impetus as institutions evolved and the scene expanded to grow more professional. Times have changed along with the situation. The last group of painters to fundamentally rearrange the Polish scene were the neo-surrealists, artistic introverts who were ‘tired of reality’ and focused on their own worlds. Local communities now seem to be a thing of the past, and modern collectives are usually short-lived, but Katowice is still probably the most interesting centre for contemporary painters.

One of the people behind that success is photographer and painter Andrzej Tobis, a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice. Graduates from his workshop include Bartek Buczek, Martyna Czech, Natalia Bażowska and Krzysztof Piętka, and Dominika Kowynia is his assistant. They definitely picked up their teacher’s flair for sensitive observation. Tobis produced a conceptual and rather utopian photographic project, A–Z: Słownik Ilustrowany Języka Niemieckiego i Polskiego (A–Z German–Polish Illustrated Dictionary). Like an actual compiler of dictionaries, Tobis undertook to describe the reality of the post-transitional borderlands.

There have been attempts to collect and assess the work of artists active in Upper Silesia: Marta Kudelska and Małgorzata Gołębiewska curated the exhibition Co Ukryte: Aktualna Sztuka ze Śląska (What is Hidden: Current Art in Silesia) at the State Art Gallery in Sopot in 2015, while Marta Lisok, a curator at the BWA Gallery in Katowice, produced Dzikusy: Nowa Sztuka ze Śląska (Savages: New Art from Silesia), a book of interviews with young artists. Melancholy is noted as a common feature of art from the region, along with a reluctance to create socially engaged art, which has brought a return to observing slices of reality, objects and landscapes. These are valid descriptions, although there is ecstasy amid the melancholy, and more engaged subjects mingle with extremely personal works.

Dominika Kowynia

‘Masaż’ (Massage) by Dominika Kowynia, 2012, photo: courtesy of the artist

‘Masaż’ (Massage) by Dominika Kowynia, 2012, photo: courtesy of the artistA few years ago, Dominika Kowynia’s paintings were elegantly academic, realist works in the style of Marcin Maciejowski. More melancholic than humorous, the artist concentrated on everyday reality, offering no social diagnoses. Her painting Łącze (Connection) shows a hooded woman in black sitting on some steps, staring into a laptop screen. Engrossed in her activity, she pays no attention to the viewer, just like the two bee-keepers by their hives in the painting Pszczelarze (Bee-Keepers). The tightly framed Masaż (Massage) is like a snapshot in a family album. It is as if the viewer is intruding on this scene of a woman with a black dog staring longingly through balcony doors. A different style dominates Kowynia’s more recent works, however – paint is applied impasto, with predominant green, grey and earthy palettes. As Wojciech Szymański remarked, these are ‘clearly distinct works that […] I would describe as a Polish version of négritude’.

Embeded gallery style

display gallery as slider

Indeed, like other artists of this school, Kowynia combines modernity with almost ethnographic elements. The stocky figures in works such as Lekcja (Lesson) are often painted in monochrome, their facial features blurred, leaving them reminiscent of rough-hewn wooden sculptures. Kowynia’s paintings are a return to childhood memories – the central theme of her exhibition Ludzie z Piasku (Sand People) at Kraków’s Widna Gallery in 2017. The artist grew up in Libya and, being the daughter of emigrants, she felt alienated and desperate to return to Poland. When it finally happened, she faced similar alienation from her Polish peers. Delving into hazy memories of that period, Kowynia blurs the boundaries and compositional clarity in her paintings. The views are cropped, their protagonists unidentified, something half-way between generic scenes and semi-hallucinations.

Martyna Czech

‘Zemsta’ (Revenge) by Martyna Czech, 100×100 cm, oil on canvas, 2017, photo: courtesy of Gruning Gallery

‘Zemsta’ (Revenge) by Martyna Czech, 100×100 cm, oil on canvas, 2017, photo: courtesy of Gruning Gallery

Martyna Czech gained wider acclaim after winning the Bielsko Autumn in 2015. Originally from Tarnów, this Katowice Academy of Fine Arts graduate’s style is closer to the new expressionism of the 1980s: aggressive, casual and unpardonably sloppy. Ever since her student days, Czech has disregarded the rules of ‘correct’ painting, concentrating instead on emotional honesty that verges on exhibitionism. Figures flash bluish teeth in grotesque smiles, their interactions generally based on physical and psychological violence, and almost all the relationships portrayed are toxic. When the artist averts her gaze from humanity, she portrays animals hanging from gallows or red-eyed and immobile, like the rabbit in her painting Zemsta (Revenge), reminiscent of a still from a horror B-movie, as if freeze-framed just before a massacre. As in such films, Czech’s furry animals have a chance to retaliate – animal suffering is a key theme in the artist’s misanthropic world. The final ingredient in Czech’s bloody carnival of canvases is sexuality – reduced to a purely biological level like any other phenomenon, stripped of all ceremony. The artist depicts a reality regulated by simple, aggressive urges that correspond to the form of her works, which are pared down to basics and rely on rapid brushstrokes, thick layers of paint, and patches of intense, solid colour.

Krzysztof Piętka

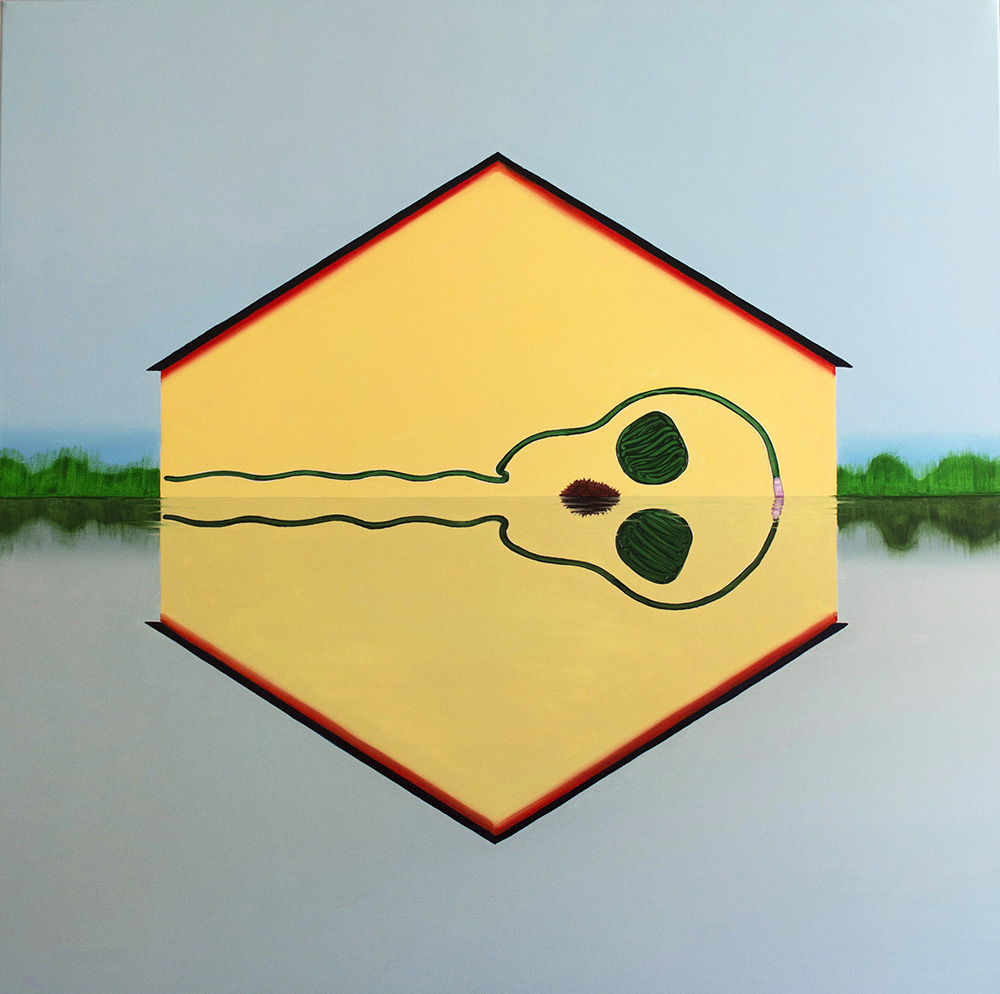

‘Śmierć Malarza’ (The Painter’s Death) by Krzysztof Piętka, 120×120 cm, oil on canvas, 2017, photo: courtesy of Gruning Gallery

‘Śmierć Malarza’ (The Painter’s Death) by Krzysztof Piętka, 120×120 cm, oil on canvas, 2017, photo: courtesy of Gruning Gallery

Krzysztof Piętka’s style has clearly been influenced by Czech, as well as Tomek Kręcicki (one of the founders of Kraków’s Potencja Gallery) and two classic 20th-century painters, Jerzy ‘Jurry’ Zieliński and Jan ‘Dobson’ Dobkowski (sometimes described as the Polish representatives of pop art). Piętka’s works are flat, almost poster-like compositions that are often quite abstract and decipherable only thanks to their titles, which can also be ambiguous at times. Piętka meddles with the viewer’s perception, and is partial to including light-hearted references to art history. In his painting Bas Jan Ader, a cyclist has flown over the handlebars and off the edge of the composition. The schematically outlined scene brings to mind a figure from a road sign or a 2D computer game. At the same time, it evokes the [eponymous] neo-avant-garde Dutch artist’s famous Fall series – short video performances that show him falling off a roof, out of a tree, and riding his bicycle into an Amsterdam canal. As well as such nods to legendary artists, Piętka also constructs his own mythology of growing up in a small town prone to flooding. In Śmierć Malarza (The Painter’s Death), a shape sketched on the side of a flooded house is reflected in the smooth surface of the water, forming the image of a skull. The work was inspired by a line painted on a house in the artist’s home town – its occupants had marked the maximum water level on one wall after a flood.

Marek Rachwalik

‘Logo i Maskotki Wiejskiej Kapelki Nu-Metalowej z Młodą Dziewczyną na Wokalu’ (Logo and Mascots of a Village Nu-Metal Band with a Young Girl on Vocals) by Marek Rachwalik, photo: courtesy of the artist

‘Logo i Maskotki Wiejskiej Kapelki Nu-Metalowej z Młodą Dziewczyną na Wokalu’ (Logo and Mascots of a Village Nu-Metal Band with a Young Girl on Vocals) by Marek Rachwalik, photo: courtesy of the artistMarek Rachwalik’s painting is ostentatiously illusory: glossy forms jut out from garish backgrounds, somehow reminiscent of 3D renders, yet he remains close to his everyday environment. His native Kłomnice and nearby villages are a major source of inspiration. His paintings are populated by fantastic cut-up car-tyre compositions painted in fluorescent colours (as seen in local gardens) combined with heavy metal iconography. A lover of grassroots creativity and metal music, Rachwalik fuses both aspects in paintings such as Logo i Maskotki Wiejskiej Kapelki Nu-Metalowej z Młodą Dziewczyną na Wokalu (Logo and Mascots of a Village Nu-Metal Band with a Young Girl on Vocals). Apart from portraying bucolic realities in potential album covers for fictional metal bands, Rachwalik also produces images such as Pestycydowy Deszcz nad Kartofliskiem (Pesticide Rain over a Potato Field) which resemble technical illustrations, Urbanowicz’s esoteric compositions, or Hilma af Klint’s theosophical paintings. Although considered neo-surrealist, Rachwalik’s structural paintings are more in line with traditions that embrace visions of a cosmic order based on religious and esoteric doctrines. Spirituality and sexuality are represented through heavy metal energy and a celebration of rural realities. Another artist, Bartosz Zaskórski, described Rachwalik’s work as follows:

Ecstasy allows [him] to transgress divisions, categories, appraisals, intellectual formulae and clichéd conventions […]. Marek’s universe celebrates and delights in becoming, constant change and mobility – even if that delight is some insane, spiky, black-metal creature brandishing a pistol over the tops of spruce trees.

Bartek Buczek

‘Czarny Charakter IX’ (Villain IX) by Bartek Buczek, photo: courtesy of the artist

‘Czarny Charakter IX’ (Villain IX) by Bartek Buczek, photo: courtesy of the artistMany artists from the Silesian community have a fascination with metal. Apart from Rachwalik, there is also Bartek Buczek, though his work is melancholic, not ecstatic. Buczek’s realistic black-and-white oil paintings portray people and objects imbued with anxiety, or visions of inexorable collapse. A series of portraits of friends, entitled Czarny Charakter (Villain), presents figures, often with their heads in shadow, covered, or turned away. Some are classical head-and-shoulders portraits, while others are very different – Czarny Charakter IX is a full-length view of a young man floating in the freezing waters of a river or a lake. He lies face down, semi-submerged and motionless at the icy water’s edge, while close by is the black spiked helmet seen in another painting from the series.

‘Czarny Charakter XIII’ (Villain XIII) by Bartek Buczek, photo: courtesy of the artist

‘Czarny Charakter XIII’ (Villain XIII) by Bartek Buczek, photo: courtesy of the artistOther canvases reveal not people but sculptural, ephemeral structures: hay bales arranged into monumental, totemic figures with staring eyes, or abstract snow sculptures. Ideal forms are damaged: Buczek re-paints Malevich’s Black Square but exposes the cracked paint on its surface, while the geometrical figure from Dürer’s Melencolia I is shown as a chipped sculpture, eroded by the passage of time. Conversely, Buczek admires common objects – he paints a cycle helmet to fill the entire canvas, rendering it unrecognisable. The glittering plastic shape perforated with oval holes is like a cross between some insect hive and a futuristic building.

Natalia Bażowska

‘Świt’ (Dawn) by Natalia Bażowska, 2013, photo: courtesy of the artist

‘Świt’ (Dawn) by Natalia Bażowska, 2013, photo: courtesy of the artistAlthough painting is merely one aspect of Natalia Bażowska’s art (alongside photography, object art and video), it is probably the most important. Bażowska is known particularly for her video performance Luna – the story of the artist’s contact with the eponymous she-wolf; an intimate, inter-species bond. Humanity’s relationship with nature forms the axis of Bażowska’s work. She avoids academic, post-humanistic analysis of the relations between human and non-human entities to focus on the emotional dimension instead.

Embeded gallery style

display gallery as slider

Surrealist iconography is her means of expression. Animal figures dissolve into black, ornamental blotches, shapes float on the backdrop of a greyish sky painted in sweeping brushstrokes, and unidentified structures tower above flat, steppe landscapes, like Yona Friedman’s utopian, pseudo-organic architectural designs. Occasionally they include abstract structures akin to the fictitious sculptures seen in Tobis’ paintings. Compared to Bażowska’s earlier canvases, she has toned down her palette in recent years. Intense colours have vanished from her work, to be replaced by greys and dirty greens, with humans downgraded to little black-clad figures, devoid of all facial features. Humankind has become just another species, treated no differently than wild animals or trees in a forest.

Originally written in Polish, Dec 2017; translated by MB, Feb 2018

[{"nid":"5688","uuid":"6aa9e079-0240-4dcb-9929-0d1cf55e03a5","type":"article","langcode":"en","field_event_date":"","title":"Challenges for Polish Prose in the Nineties","field_introduction":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary\r\n","field_summary":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary","topics_data":"a:2:{i:0;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259609\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:26:\u0022#language \u0026amp; literature\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:27:\u0022\/topics\/language-literature\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}i:1;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259644\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:8:\u0022#culture\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:14:\u0022\/topic\/culture\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}}","field_cover_display":"default","image_title":"","image_alt":"","image_360_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/360_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ZsoNNVXJ","image_260_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/260_auto_cover\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=pLlgriOu","image_560_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/560_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=0n3ZgoL3","image_860_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/860_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ELffe8-z","image_1160_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/1160_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=XazO3DM5","field_video_media":"","field_media_video_file":"","field_media_video_embed":"","field_gallery_pictures":"","field_duration":"","cover_height":"991","cover_width":"1000","cover_ratio_percent":"99.1","path":"en\/node\/5688","path_node":"\/en\/node\/5688"}]