Popular Culture

Uklański's ‘speciality’ is transporting different aesthetic phenomena through space and time. His Dance Floor project from 1996 is a floor ‘quoted’ from a nightclub, pulsating with light to the rhythm of dance music. Installed inside a gallery, it becomes an element visitors cannot pass by. They are confronted with a space which atmosphere is reminiscent of a disco, but they may be frustrated by the fact that they are unable to succumb completely to the mood. The project is also a dialogue with traditional minimalist sculpture.

Piotr Uklański, The Nazis, 2000 and Dance Floor 1996, installations view, Courtesy of the Zacheta National Gallery of ArtAt the invitation of the Foksal Gallery, in 1999 Uklański made a ceramic mosaic from broken plates – production waste from the Ćmielów and Pruszków ceramic tableware factories – on a pillar at the entrance to the Smyk department store in the centre of Warsaw. He was inspired by a journey across Poland during which he noticed many houses decorated with mirrors and fragments of tableware. The artist picked up this kitschy decoration of provincial architecture and used the method in a different social and aesthetic context, changing the scale to monumental, and low-brow culture to high-brow.

Uklański's exhibition The Nazis, shown at Warsaw's Zachęta gallery in November 2000, ended with a scandal; several works were destroyed and the exhibition was closed down. The project comprised a series of 164 colour photographs of well-known foreign and Polish actors who had played Nazis in films. Using a tool typical of mass culture, the artist collated the film portrayals of the ‘evil German’ which haunt the audience's collective imagination. The photos show handsome, elegant men, tough guys of film seducing the viewer with their attractive image, thus blurring the truth about Nazism. The artist himself commented on the project:

The portrait of a Nazi in mass culture is the most prominent example of how the truth about history, about people is distorted. This is all the more important to me in that this is the main source of information about those times, and for many people – the only one.

When the exhibition was on display, well-known actor Daniel Olbrychski entered the gallery with a sword and, in the presence of a television crew who had been warned in advance, slashed several of the pictures in protest against the artist having used his film image. The minister of culture refused to allow the exhibition to be reopened.

Piotr Uklański, a ceramic mosaic at the entrance to the Smyk departmrnt store in Warsaw, 1999, photo: courtesy of Foksal Gallery Foundation

Piotr Uklański, a ceramic mosaic at the entrance to the Smyk departmrnt store in Warsaw, 1999, photo: courtesy of Foksal Gallery FoundationFor the Love of Kitsch

He has also made use of associations connected to the graphic symbol of Solidarity to create abstract works that play upon the evolution of what the movement means for subsequent generations. His show White-Red presented a number of such works inspired by the legacy of Poles brought up under communism and then set free in democracy as adults. White-Red was shown in such prestigious galleries as the Gagosian in New York City in 2008 and Brussels' BOZAR in 2011 as part of the group show The Power of Fantasy: Modern and Contemporary Art from Poland.

Since 1997 Uklański has been carrying out an open project called Joy of Photography, in which he's taken a series of iconic photographs presenting the beauty to be seen in flowers, sunsets, exotic animals, or picturesque landscapes. The artist tracks down manifestations of beauty in spite of the label of kitsch which unavoidably accompanies this concept, highlighting its symbolic topicality while questioning the stereotype of art photographers and the themes they should be concerned with.

Two of Uklański’s works based on the same idea conform to the convention of ‘beautiful’ kitschy composition. The first one titled Foksal Gallery (425 x 230 cm) and displayed at the Foksal Gallery Foundation in Warsaw in 2002 was a digitally processed snap of silhouettes of curators and artists associated with the gallery photographed earlier in a studio against a sunset backdrop selected from a commercial catalogue. It pictured Marianne Zamecznik, Mirosław Bałka, Adam Szymczyk, Cezary Bodzianowski, Wiesław Borowski, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, Anna Niesterowicz, and the artist himself. A year later at the Venice Biennale Uklański showed a similar work in a banner format, with the silhouettes of curators of the 50th Biennial against a red background (Untitled / OT).

Uklański overtly takes pleasure in mocking and provoking the art world in a flippant way, as evidenced by a publication of a photograph showing the buttocks of Alison Gingeras, a curator of the Centre Pompidou in Paris and privately the artist’s partner published in the Artforum magazine in 2003. The photograph titled Ginger Ass was signed by Uklański and accompanied by a curatorial text that read:

The curve of my back suggests that I am slightly bending and sticking out my behind toward the camera lens. As if I was asking for a proper spank, or maybe wanted something completely different. An art curator certainly should not strike such a pose in front of the artist.

Uklański spent a few thousand dollars on publication of this material, but the investment definitely paid off – his name’s been on everyone's lips.

The Image of the Pope

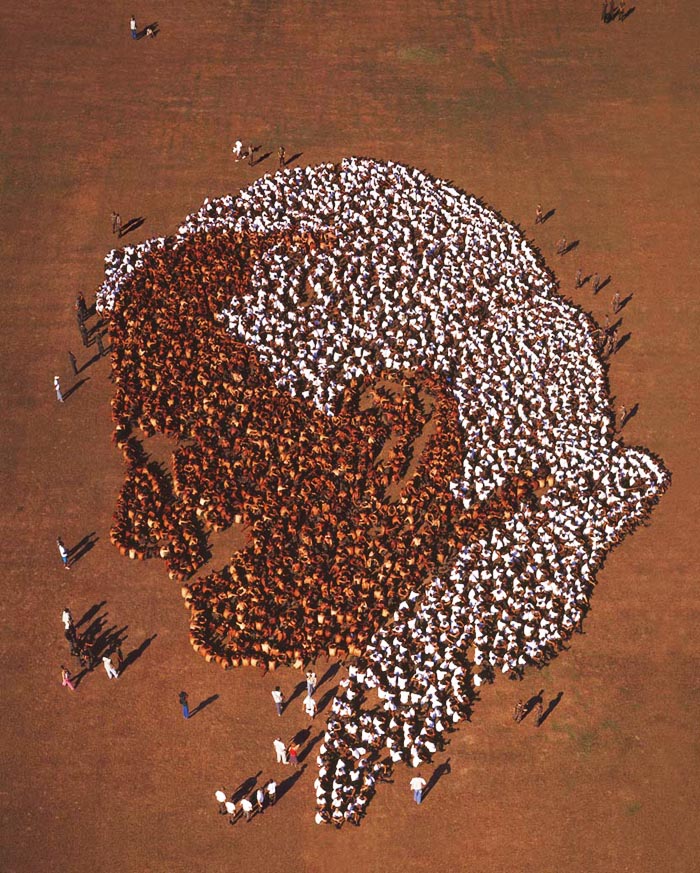

Piotr Uklański, Untitled (Pope John Paul II), 2004, photo: courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

Piotr Uklański, Untitled (Pope John Paul II), 2004, photo: courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art in WarsawIn 2004 the director of the Kunsthalle in Basel invited Uklański to put on a solo show. The exhibition Piotr Uklański – Earth, Wind and Fire was accompanied by a lavish catalogue-album. On the outer wall of the gallery the artist installed a giant mosaic of broken tableware in white and red and showing a sunset. It was a new version of the project carried out five years earlier on the wall of Smyk department store. The exhibition was advertised by a poster portraying the artist as a young man. The black-and-white photograph pictured a James Dean-lookalike Uklański wearing a mohawk and a leather jacket on his naked torso.

In the same year, Uklański represented Polish art at the São Paulo Biennale. He showed a monumental photograph measuring 4 × 5 m which showed Pope John Paul II's head. In order to produce it, the artist set up a mass event to which he invited approximately 3.5 thousand Brazilian soldiers, asking them to line up along the contours of the Pope's head drawn on the ground. The face was filled in with soldiers who were asked to remove their tops, while the Pope's Zucchetto was formed by the rest, who wore white shirts. Thus created monumental drawing was then photographed from the bird's eye view. The work was created in three principal forms: large format photograph, a smaller photographic print, and a billboard. The artist said:

I created a portrait of the Pope with the help of the army and with the participation of representatives of different races. (...) For me, this work conveys a message of peace.

A year later, the photograph of the Pope hung on the scaffolding mounted near the crossing of Marszałkowska and Świętokrzyska Street in Warsaw anticipating the construction of the Museum of Modern Art in this location.

In 2007 Uklański repeated the concept of the work at Gdańsk Shipyard, this time inviting Polish soldiers to help him compose the logo of the Solidarity movement. The artist has received support from the organizers of the Festival of Stars in Kołobrzeg, and one of five copies of the photograph was purchased by the National Museum in Gdańsk. Uklański declared that rather than a personal tribute to the Solidarity, it was an attempt at investigating whether this sign (which in his opinion had become empty and devoid of significance) still carries any meaning.

National Symbols

Piotr Uklański, Deutsch-Polnische Freundschaft, 2011, photo: Bartosz Stawiarski, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

Piotr Uklański, Deutsch-Polnische Freundschaft, 2011, photo: Bartosz Stawiarski, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw The artist willingly uses symbols from the repository of the Polish national iconography. At the exhibition Polonia held at Emmanuel Perrotin’s gallery in Paris (2005) Uklański showed a white and red Flag made of enamel and glass and a sculpture of Polish emblem, an eagle. He significantly expanded this topic at the exhibition White-red at the New York Gagosian Gallery (2008) referring also to the tradition of the Warsaw Uprising (shiny abstract paintings made of big, luscious pours of red and white resin reminding of dripping blood and signed with names of Warsaw’s districts where the fighting took place), Solidarity (political struggle commemorated in two photographs of the Solidarity logo spelled out on the docks at Gdańsk by masses of men wearing white or red) and to the drawing by Stanisław Szukalski which became the prototype of the sculpture of the Slavic eagle, also known as Stach’s Eagle.

Piotr Uklański also wrote and directed the feature-length film Summer Love (2006). Shot in southern Poland with a mainly Polish cast (although the dialogue is in English), the film's stock characters are instantly recognizable to viewers for whom the myth of the American West is ingrained by the Westerns of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Yet Uklanski's film is ‘a copy of a copy’, referring to the European spaghetti Westerns as much as to the American ‘original’. It exploits cinema's most codified genre to address issues of cultural authenticity. With its impressive cinematography and strong performances, including an appearance by Hollywood star Val Kilmer, Summer Love functions not only as a conceptual statement, but also as a genuine Western, adding to the grand tradition of the genre. The film premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2006, and earned him nomination for the Gucci Group Award in 2007.

Over the years Uklański has been working on a series of portraits of people whose public function dominates their private life. Contrary to expectations related to photography as a mimetic medium Uklański’s portraits do not bear resemblance to their models, but rather misrepresent them. He explained his objective as follows:

So being in front of a camera is more of a metaphor. I was interested in this question of, how can you take a picture of somebody and not care about what the so-called ‘truth’ is? Or instead of trying to portray a likeness, to look for a symbol almost, like a graphic symbol, that may communicate this.

As a result of such approach the portrait of the former French Minister of Culture Jean-Jacques Aillagon pictures a blurry figure rising from a chair. The portrait of President Luiz Inácio Lula resembles a playing card: the president sits at the table with a shiny surface which vaguely reflects his body. The portrait of a famous art collector François Pinault, based on a colour CAT scan of his face, shows a brightly-coloured skull with crossbones and is reminiscent of a pirate, alluding to the methods of acquiring works of art by collectors.

In 2008 Uklański took part in the 5th Berlin Biennale. In front of the building of the Neue Nationalgalerie he installed the enormous clenched Fist (a symbol of resistance in the face of violence) made of steel tubes, declaring that:

It is not a manifestation of my political views. In the context of the Biennale in Berlin and with regard to the location of the work, I would see it rather as my own 'Kozakiewicz’s gesture.'

Return to Craft

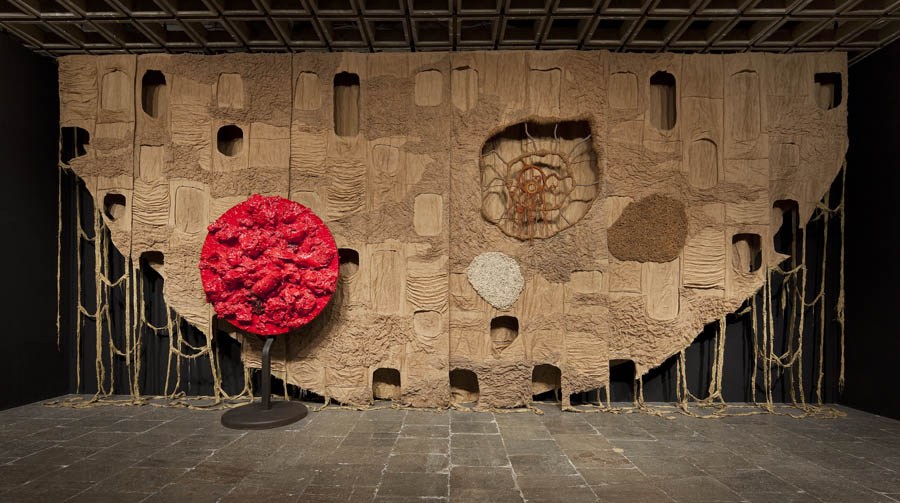

Piotr Uklański, Untitled (The Year We Made Contact), 2010, installation view at Whitney Biennale, Whitney Museum, Nowy Jork, 2010, courtesy of the artiest, photo: Zachęta National Gallery of Art

Piotr Uklański, Untitled (The Year We Made Contact), 2010, installation view at Whitney Biennale, Whitney Museum, Nowy Jork, 2010, courtesy of the artiest, photo: Zachęta National Gallery of ArtPiotr Uklański is an unpredictable artist. He's constantly looking for new aesthetics and forms, which he then appropriates for his own use and makes new meanings and senses out of them; reactivating them in different and usually surprising contexts. Pop culture is his main source but he also reaches for seemingly dead traditions.

After an artistic reanimation of Polish national mythology with the exhibition White-Red, the artist has been developing a theoretical reflection on the Polish art of the 1960s. In 2010 Uklański showed an installation called The Year We Made Contact at Whitney Biennial in New York Its main element was a monumental fabric made of hempen and hessian strings, that makes us think of Magdalena Abakanowicz’s tapestry, Józef Szajna’s plastic theatre and Tadeusz Kantor’s informel art. The fabric is compiled with a painting Red Dwarf. The title The Year We Made Contact refers to the 1984, Peter Hyams’s sequel of Stanley Kubricks’ famous 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Piotr Uklański’s works made for Whitney Biennial were bought by Grażyna Kulczyk and presented at the turn of 2010 and 2011 in Poznań at Tadeusz Kantor, Piotr Ukłański – The Year We Made Contact. Its organizers highlighted that:

The idea of such juxtaposition gives an outstanding opportunity to abstract those characteristics and forms of expression which inspired the young artist. The presence of original linens and mannequins made by the Cricot 2 Theatre’s creator plays an important role in interpreting the work, as it emphasizes the role of tradition and those elements of Uklański’s work that are submitted to it.

In the individual exhibition Discharge! (2011) at Gagosian Gallery in New York the artist referred to the tradition of anti-painting by showing a series of paintings done without paint. Colourful cotton sheets bought in Ikea and Bloomingdales were stretched on a canvas stretcher and whitened. The final effect of this artistic process were forms that resembled either organic patterns visible only under a microscope or pictures of outer space. This artistic gesture contradicts the idea of paintings traditionally hung on a wall, because the paintings in Uklański’s work merge into the background. In a smaller room of the gallery the artist placed a big bas-relief made of ceramic bowls, pots and plates. In both cases the artist used mass produced goods, sheets and ceramic to create a new way of expression, equivalent to conventional artistic measures.

In 2010 Piotr Ukłański’s Early Works album was published by 40 000 Malarzy publishing on which the artist commented:

It is my most realistic portrait. However, I do not believe in realism. The reality can’t be represented. One can only convey a certain version of reality using conventional signs.

The book consists of Uklański’s childhood drawings analysed by a child psychologist Agnieszka Ziętek. The artist remarked:

The collections of artists’ early drawings are usually accompanied by texts that define them. On the one hand, I was interested in the convention of such compilations, on the other – I wanted to find out something new about my works. A child psychologist seemed more adequate for such task than an art critic. I was surprised to find out how many unexpected things those paintings revealed. I began to pay more attention to details.

Jakub Banasiak, the publisher of the album added:

First and foremost it is a kind of self-portrait, only proffered in a perverse way. Uklański’s book is also a sophisticated game with the convention of an ‘album about art’. At the same time Uklański plays with his public image, which is one of his artistic strategies.

Art of Appropriation

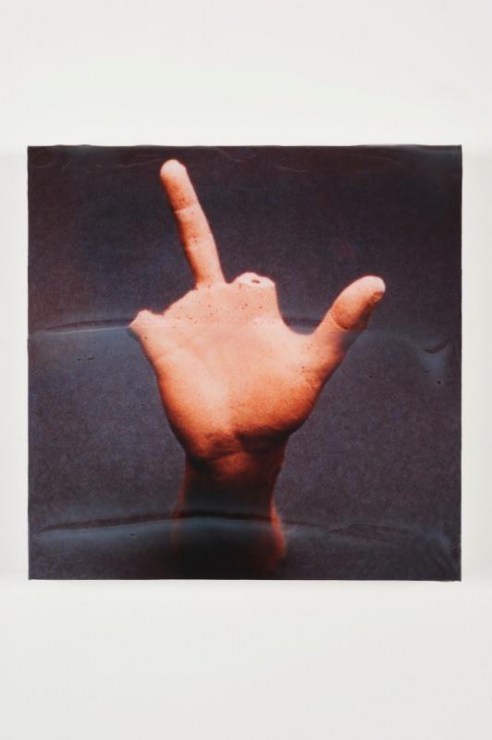

Piotr Uklański, Untitled (Polish Neo Avant-garde; Jan S. Wojciechowski, Hand, 1974), 2012, ink print on canvas and acrylic polymer, photo: courtesy of thye artist and Massimo De Carlo Gallery, London-Milan / source: artmuseum.pl

Piotr Uklański, Untitled (Polish Neo Avant-garde; Jan S. Wojciechowski, Hand, 1974), 2012, ink print on canvas and acrylic polymer, photo: courtesy of thye artist and Massimo De Carlo Gallery, London-Milan / source: artmuseum.plIn 2012, the Zachęta National Gallery of Art held the first ever exhibition of Uklański's work. Designed entirely by the artist Forty and Four was conceived as a deliberately eclectic mix of works presented through immersive installations and mise-en-scènes that convey his aesthetic vision rooted in the tradition of the Gesamtkunstwerk. For example, Uklański has transformed one of Zacheta’s pristine neoclassical gallery rooms into a womb-like environment made from suspended, discharge-dyed fabrics. It served as the scenography for the display of a suite of Uklański’s paintings and photographs, including pencil-shaving paintings, ceramic mosaics, resin paintings and other examples of Uklański’s metapainting practice.

Should one investigate Uklański’s work in order to identify its main theme, it would be the porous border that separates the generic from the beautiful, the transgressive from the banal. Uklański dares to conflate pleasure and criticism in the same work – a heretical gesture that in most art world circles is considered more inflammatory than his freauently controversial subject matter (such as Nazis, Pornalikes or Untitled (GingerAss), 2003). This subversive conflation often renders the ‘critical’ or political function of Uklański’s work suspect for many art historians and critics, as well as for the general public. But the critical meaning of Uklański’s work lies precisely in the ambiguous, unstable messages that emanate from such a conceptual tension.

In addition to the well-known earlier works such as Dance Floor and Nazis, the Zachęta gallery showed the series Polish Neo Avant-garde presented for the first time to Polish audiences. The show was much talked about even before its opening. When shown in London's Carlson gallery in 2012 it sparked outrage and led to accusations of plagiarism. Uklański used reproductions of works by Polish artists from the 1970s, such as Wiktor Gutt and Zbigniew Warpechowski to create his own works.

Uklański’s work Polish Neo Avant-garde is situated, just as the rest of his work, at the crossroads of various incompatible artistic traditions. On the one hand, it refers to the American tradition of appropriation art. On the other, it is a sui generis continuation of the artist’s activities intended to revitalize the Polish neo-avant-garde of the 1970s. Uklański – a pupil of artists that were at the heart of this trend – was a co-publisher as well as author of the publishing concept behind Łukasz Ronduda’s book Polish Art of the 1970s: Avant-garde, which contributed to restoring the hitherto-marginalized radical artists of the 70s to their deserved place.