Nikifor was Lemko on his mother's side, and his father was Polish – legend has it that he was also a recognized painter who went by the name of "T". Nikifor's mother raised him on her own in conditions of extreme poverty and hardship, earning a living through various odd jobs and housework. He inherited a hearing and speech impediment from her. Orphaned during World War I and unable to communicate with the people around him, Nikifor was initially treated like a misfit and ridiculed by the people of Krynica. He found himself isolated both physically and emotionally.

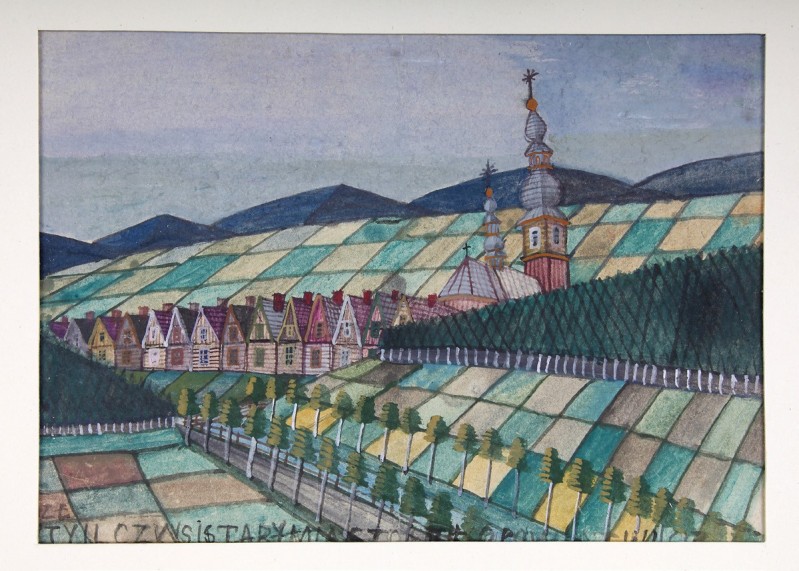

Nikifor Krynicki, Mountain landscape, photo courtesy of The Ethnographic Museum in Kraków

Nikifor Krynicki, Mountain landscape, photo courtesy of The Ethnographic Museum in KrakówThe origins of the nickname "Nikifor" are unknown, but he began using it as a child (the original version of the name was apparently "Netyfor"). For a long time he used no surname at all. For the first exhibition of his works, mounted in Warsaw at the Polish Architects' Association (SARP), posters were printed identifying him as "Jan Nikifor". It wasn't until 1963 that he was officially given the surname "Krynicki", and, his administrative status finally resolved, he was given a flat by the Krynica authorities. In 2003, however, the local court in Muszyna declared that his real name was Epifaniusz (Epifan) Drowniak.

We also don't know when he started to draw and paint. From the very beginning, however, he was clearly focused on the target he had set for himself: to become a painter, a Matejko from Krynica.

Nikifor was a local patriot – although he was relocated twice to a remote corner of Poland under the Akcja Wisla (the Polish Army's 1947 relocation of south-eastern Poland's Ukrainians, Boykos and Lemkos), he stubbornly returned to his home town each time.

Many of Nikifor's earliest preserved works, which date from before 1920, reveal his efforts to perfect his skills. As Tadeusz Szczepanek wrote:

The majority of the preserved drawings are study sketches par excellence, complete with erasure and correction marks. Nikifor was striving to master convergent perspective, plotting axes of symmetry, moving the crossing point of lines to other spots and testing his ability to see things from the perspective of the frog and the bird.

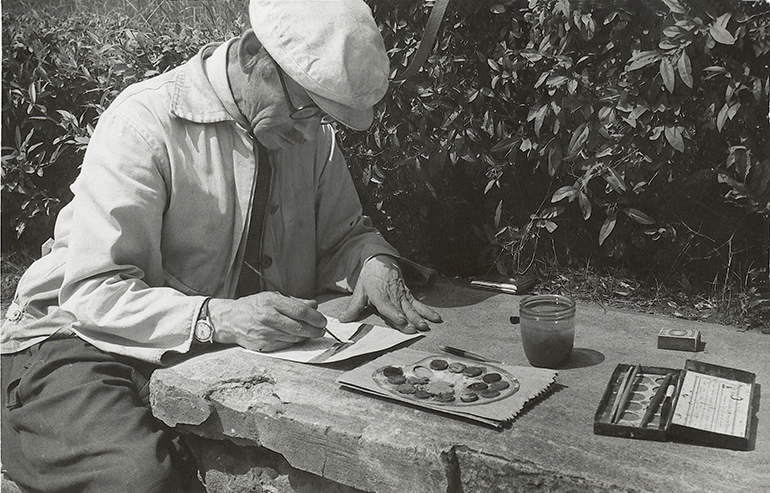

Nikifor Krynicki working in Krynica, reproduction: FoKa / Forum

Nikifor Krynicki working in Krynica, reproduction: FoKa / ForumThe same learning process is apparent when browsing through Nikifor's sketch-book of sacred architecture. Dating from a few years later, it is devoted to a topic the artist found particularly inspiring: the Greek Catholic church. Indeed, many of his works are landscapes with the outline of a church in the background (such as Cerkiew o zachodzie slonca / A Church at Sunset (1920s), Biskup przed cerkwia / A Bishop in Front of the Church (ca. 1930) and Cerkiew w miasteczku / A Small-Town Church (ca. 1962). Others are sketches of church interiors (Kapliczka / A Chapel (ca. 1930) and Ostatnia wieczerza / The Last Supper (undated), or hieratic images of saints (Swiety Mikolaj / Saint Nicholas (1920s) and Swiety na drodze / A Saint on the Road (pre-1956). But he used secular themes as well, including a number of Krynica landscapes (Krynica – Pijalnia / Krynica - The Pump Room (1930s), Niebieska Willa / A Blue Villa (1950–1955), Kościół w Krynicy / The Church in Krynica (pre-1962) and Willa "Zacheta" / Villa "Zacheta", Willa "Rusałeczka" / Villa "Rusałeczka" and Budynek Przedsiebiorstwa Ogrodniczego / The Building of the Gardening Company, all from 1940–1945). Cracow landscapes appear as well, although they are less numerous (Krakow – Kosciol Mariacki / Krakow – St Mary's Church (1964–1966)), along with Warsaw landscapes (Pejzaz miejski - Warszawa / A City Landscape – Warsaw (1965).

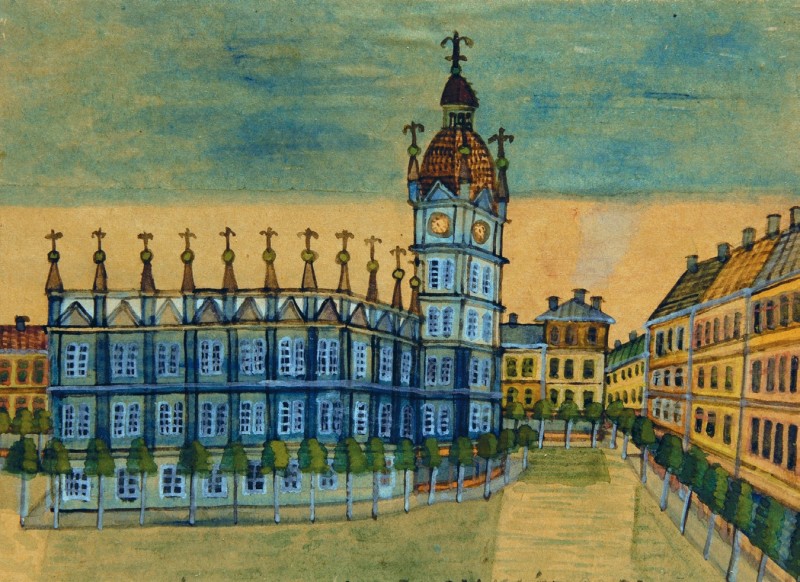

Nikifor also took an interest in architecture, as can be seen in pieces like Fragment architektury miejskiej / A View of Town Architecture (1930), although sometimes his creations were pure fantasy (Brama fantastyczna / A Fantastic Gate (undated). He drew interiors as well (U fryzjera / At the Barber's , U Krawca / At the Tailor's and Trafika / The Newsagent's, all from 1930s), and was particularly fascinated by railway stations and railway tracks winding through the hills (Tory kolejowe / Railway Tracks, Stacja Bihcz / Bihcz Station and Krajobraz z mostem kolejowym / Landscape with A Railway Bridge, 1930s). Mountain views also appear in his work (Drewniany domek na tle pól / A Wooden House in the Fields (1940–1945), Pejzaz gorski z wsia / A Mountain Landscape with a Village and Pejzaż z rzeką / A Landscape with a River (both pre-1956).

Nikifor Krynicki, Cracow, photo courtesy of The Ethnographic Museum in Kraków

Nikifor Krynicki, Cracow, photo courtesy of The Ethnographic Museum in KrakówWhen it came to people, Nikifor liked to portray acquaintances and passers-by (Na przechadzce / Taking a Walk (1920s) and Portret mezczyzny w plaszczu i z laska / A Portrait of a Man in a Coat with a Walking Stick (1950–1953), but even more, he liked to portray himself. His numerous self-portraits, painted in the 1930s, are extremely interesting. They show his self-consciousness and awareness of his position, as well as his vision of himself and his aspirations (he liked being photographed, too). He would depict himself absorbed in thought, sitting under the trees, dressed up, sitting by an easel, having a meal, raising his hand in a gesture of blessing or standing behind an altar (Nikifor w peruce / Nikifor Wearing a Wig, Nikifor nauczajacy / Nikifor Teaching). He is also shown in the niche of a church (Nikifor biskup / Nikifor the Bishop) or at the church door (Nikifor rozsylajacy uczniow / Nikifor Sending Out Disciples). Many of the works bear clumsy but legible inscriptions that read "Painter" or "A keepsake of Krynica".

Regardless of the theme, Nikifor's works are small, often not much larger than a sheet of paper from a copybook. Initially he would use any scraps of paper he was given – Austrian office forms, used school copybooks, chocolate wrappers, cigarette boxes or wrapping paper. In a thriftiness that stemmed from his poverty, he would often make double-sided pictures (Chrystus nauczający – Chrystus błogosławiący / Christ Teaching – Christ Blessing, Święta Barbara – Kapliczka / St Barbara – A Chapel and Święta Weronika – Chrystus w Świątyni / St Veronica – Christ in the Temple (ca. 1920).

Nikifor liked to paint with watercolours, sometimes combining them with tempera or oils. In his final years he also began using crayons. The strength of his work, however, stems from its ability to transcend all limitations. Even using a small format, he was able to produce monumental images through a central composition with a distinct, frontal view – on the axis of symmetry – of the vertical rectangle of a human shape, a building or a mountain. He would often frame his landscapes, scenes or portraits with ornamental borders (Święci na drodze / Saints on the Road (pre-1956)) and carefully outlined each element with a thin black line, filling it with vivid colours applied straight from the tube. His paints lost their raw quality as his intuitive and inspired approach produced rich nuances. He was able to achieve a fullness of colour and a full range of shades of each colour, and was able to use his palette to evoke moods – most often the mood of nostalgia.

Krystyna Feldman in Krzysztof Krauze movie My Nikifor, photo: Best Film

Krystyna Feldman in Krzysztof Krauze movie My Nikifor, photo: Best FilmExpert opinion is that the finest of Nikifor's tens of thousands of works are the ones he created in the 1920s and 1930s, by which time he had defined both his favourite themes and his sense of aesthetics. Extreme poverty meant that he had to give away many of his works or sell them for mere pennies. His talent was first recognized by the Ukrainian painter Roman Turyn, the first collector of Nikifor's watercolours, who acquired almost two hundred of them. While in Paris he showed them to friends of his, members of the Komitet Paryski (the Paris Committee, later abbreviated to "Capists"); they were impressed, and attempted to hold a solo exhibition in Paris of Nikifor's work. In the end they did not succeed, but they did manage to include some of his "little pictures" in a group exhibition of Lvov and École de Paris painters, organized in 1932 by the Ukrainian National Museum in Lvov. Jerzy Wolff, Nikifor's advocate and author of the first publication about him ("Arkady", 1938, no 3), wrote of the Capists' reaction to the Krynica artist's works:

My friend and I were first introduced to (Nikifor's) art in Paris a couple of years ago. This initial contact was ravishing. I still remember the moment when I first stood in front of these little watercolours in Jan Cybis's workshop, and I am still filled with awe. I was struck by the unusual maturity and [...] distinctiveness of these works. [...] Over the centuries countless pieces of canvas and board had been painted, yet these scraps of paper were unlike [...] anything I had ever seen. [...] These little pictures are as simple as nature, and their uniqueness lies solely in truly seeing reality through eyes that are different from everybody else's ... Like perfect pitch, Nikifor's perfect sensitivity to colour reflects [...] our own dreams of painting.

He added:

(Nikifor) always works in ranges, every picture of his including at least three colour combinations; these are very strange, but at the same time they are faultless. Their strangeness comes from his abstract approach to painting, yet this abstraction is in no way unreal. His world is always perfectly real. However, he finds it necessary to separate himself from the object so that he can create it through painting.