Written originally in French by Polish aristocrat Jan Potocki, the piece has consistently fascinated and perplexed both readers and scholars. The latter have variously labeled the book as romance, fantasy, or gothic horror ‒ which undoubtedly reflects the highly original and innovative character of the book, written in the beginning of the 19th century. Some have gone as far as to call Potocki a Post-Modern author avant la lettre.

While recent sensational archival finds may have helped to shed new light on the circumstances under which the book was created, the Manuscript remains as controversial as ever, all the more so since one potential explanation of its intricacies entails a journey into the realm of the Kabbalah.

Uładówka, Christmas Eve 1815

Giambattista Lampi, "Jan Potocki with the pyramides", 1804, oil on canvas, Łańcut Museum, fot. East News

Giambattista Lampi, "Jan Potocki with the pyramides", 1804, oil on canvas, Łańcut Museum, fot. East NewsPotocki's death is shrouded in mystery but one thing is certain: on December 24 1815 Count Jan Potocki commited suicide in his Uładówka residence (in modern-day Ukraine). According to legend, he shot himself with a silver knob taken from the handle of a sugar-bowl, which he had been polishing for the past several weeks ‒ possibly in a fit of prolonged melancholia. Later speculation connected the silver bullet with rumors that the count had been a werewolf.

More reasonably, others have tried to see in Potocki's last act a deliberately gory spectacle meant as a lesson in practical philosophy for his long-time friend Stanisław Chołoniewski, who was one of the first persons to see the count's body. Chołoniewski was Potocki's neighbour, a kind of intellectual disciple, with whom Potocki had engaged in an enduring philosophical dispute.

On the fatal day Potocki invited Chołoniewski to join him later at his residence. When Chołoniewski arrived at his mentor's manor he found his host lying on the bed, his face disfigured by the gunshot. In a memorable account of those macabre circumstances, Chołoniewski noted that Potocki's brain had splattered the walls and the floor. ’One of us slipped on Potocki's brain,’ recalled the priest, who had come to the palace with a friend.

Did Potocki try to lure his young friend into this gory show? Was he sending a message? And if so, what was it? But before we shed light on that gruesome day, we have to take a look at the fascinating story behind the making of Potocki's magnum opus and its various manuscripts ‒ a story which is just as obscure and labyrinthine as the Manuscript itself.

The Manuscript found in Poznań

The cover of the new Polish edition of the Manuscript based on the archival finds of Rosset & Triaire

The cover of the new Polish edition of the Manuscript based on the archival finds of Rosset & TriaireDuring his lifetime Potocki never published the Manuscript in its entirety. For some reasons he felt enticed to publish his opus magnum in fragments, a fact which resulted in a confusion that prevails to this day. The fragments which he did publish in Saint-Petersburg and Paris certainly raised interest and spawned several plagiarised publications during the count's life ‒ another confusing element. As a result, when Potocki died in 1815 there existed no authoritative final version of his book – instead there were many apocryphal copies and imitations which circulated around Europe.

For reasons that remain obscure, the Potocki family was not immediately interested in popularising the work and legacy of the count upon his death. As a result, the work was not published until 1847 – some 30 years after the count's suicide ‒ when a Polish translation made from an autographed version came out in Leipzig. Unfortunately, almost immediately after the publication the original French manuscript disappeared.

As a result, the Polish translation is now the Manuscript as we know it, becoming the source of many other versions and translations, including, ironically, the popular French version of 1989 ‒ the last part of which was translated from a German translation of this Polish translation! The Manuscript was already a patchwork running on a legend, but nevertheless it had few serious readers.

This chaos could have lasted longer if not for the sensational find made by two French scholars researching Potocki in Polish libraries at the turn of the last century. In 2002, at the Poznań's National Archive François Rosset and Dominique Triaire found an unknown version of the Manuscript dated with watermarks. From this they were able to conclude that there were in fact two authentic versions of the book which they called version de 1804 and version de 1810.

The two versions differed largely as they reflected the fluctuating philosophical concept of the work in Potocki's mind. It was these two versions, Rosset and Triare claimed, that were then manipulated and conflated by Chojecki in his 1847 translation, which since then has become what we know as The Manuscript Found in Saragossa.

Since the publication of Rosset's and Triaire's book in 2005, their hypothesis has become almost universally accepted by Potocki researchers since it explains many controversies and establishes new ground for interpreting the text. For one, the new Polish translation (the first one since 1847!) published in 2015 by Anna Wasilewska follows closely the findings of Triaire and Rosset. However not everyone is convinced.

The Manuscript and the Kabballah

Among those not convinced of the existence of the two versions, there is Michał Otorowski, a Potocki scholar who has devoted most of his research to tracing the inherent intricacies of Potocki's literary maze, as well as its ramifications and potential cross-pollinations in the works of other writers of cognate spirit (those who also wrote about conspiracy theories, secret organizations and messianism). From the various articles and books Otorowski published about the Manuscript one could almost infer that he considers the book a sacred masterpiece of arcane knowledge. But, more importantly, Otorowski also claims to have found the key to this elusive knowledge. This key is the Kabbalah. Or to be more precise, the Lurianic Kabbalah, a messianic system of Jewish thought created by Isaac Luria during the 16th century.

Unlike many other scholars Otorowski believes that The Manuscript Found in Saragossa is not just an Enlightenment romance encapsulating a series of anecdotes told in a mise-en-abîme or frame narrative (as it is also sometimes called). The author of Jan Potocki: Koniec i początek (author’s translation, Jan Potocki: The End and the Beginning) claims that Potocki's work is in essence an initiate text in which the protagonist Alfons van Worden sets out on a spiritual journey that tests and challenges his knowledge about the world and contributes to his ultimate transformation.

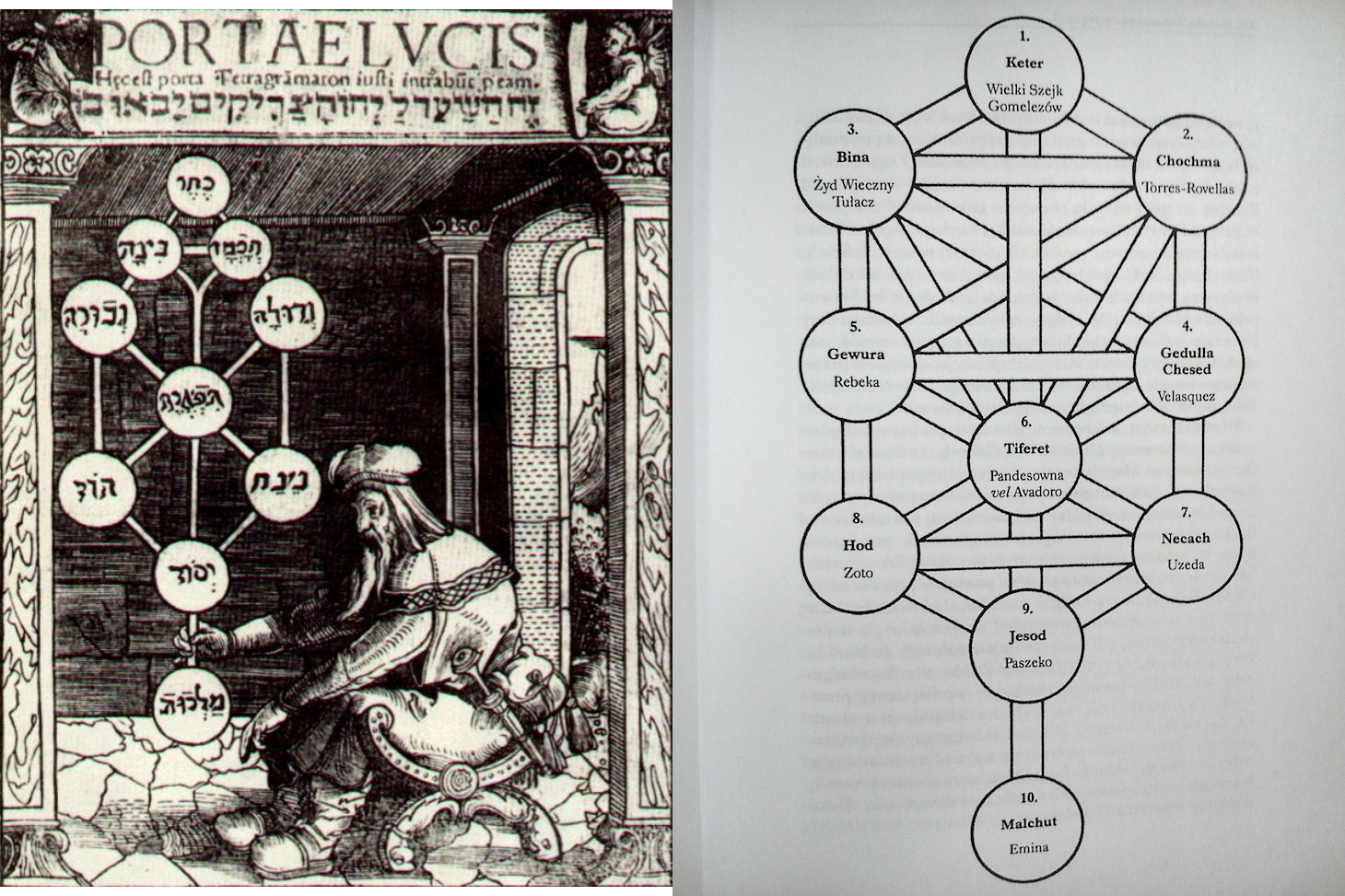

The path which he takes is defined by the ten narrators (present in the canonical Chojecki translation from 1847) which according to Otorowski represent the ten sephirot of the Kabbalah. (In the Jewish kabbalistic tradition the sephirot are usually defined as the representation of God's attributes and the principle of Creation.)

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life - the diagram on the right shows the relation between the ten sephirot and ten narrators of the Manuscript Found in Saragossa (1847 version); Source: Michał Otorowski, Jan Potocki: Koniec i początek (2008)

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life - the diagram on the right shows the relation between the ten sephirot and ten narrators of the Manuscript Found in Saragossa (1847 version); Source: Michał Otorowski, Jan Potocki: Koniec i początek (2008)Thus, the quest of Van Worden becomes, in Otorowski's view, the ascending path up the Kabbalistic Tree of Life: from the lowest 10th sephira of Kingdom (Malchut / regnum), represented in the book by princess Emina, to the highest sephira of the Crown (Keter/Corona) ‒ personified in the text by the Sheikh Gomelez. The specific relations between the narratives and a loose composition of the work itself (again we're talking about the 1847 version) is, according to Otorowski, best explained not by the mise-en-abîme or frame tale structure, but by the 22 channels which connect the sephirot in Kabbalistic tradition.

On a larger plane, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa as read by Otorowski is a tale (or manual) of the potential mending of the world ‒ its rectification, as the Kabbalistic term tikkun is often translated. Only in Potocki's esoteric teaching, this will be done not by the Messiah or the Chosen People but by all of mankind.

In this respect, Otorowski speaks consistently not of the 1804 and 1810 versions , but rather the esoteric and the exoteric version of the text. Obviously among these two only the former retains a Kabbalistic core, while the exoteric version of 1810 results from an intellectual crisis and possibly reflects the change in Potocki's scientific approach to ancient chronology ‒ the count's main field of scholarly interests (an issue certainly too complex to discuss at length). Luckily ’Potocki managed to salvage from that personal and intellectual crisis a masterpiece ‒ a masterpiece on which he had worked incredibly long, and which he almost ruined completely,’ concludes Otorowski. And he means the Chojecki version of 1847.

The Death of the Cabbalist?

A still from the movie The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, starring Zbigniew Cybulski., photo: Polfilm / East News

A still from the movie The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, starring Zbigniew Cybulski., photo: Polfilm / East NewsAmong the multitude of questions that could be naturally be asked at this point, one stands out. Namely, why would Potocki have developed an interest in Kabbalah? Naturally as an aristocrat and scientist, he could have followed any fancy he liked ‒ he had all the resources and curiosity needed for that. However, one geographic trace may be particularly interesting.

Potocki spent his early years in a remote area of Ukraine. This region also happens to be the scene of a massive expansion of Jewish Messianic movements in 17th and 18th centuries, all embedded in the Kabbalah tradition of Zohar. For one, this was the area that engendered the figure of Jacob Frank, a reformer of Judaism and possibly a charlatan, born in 1726 in Korolivka in Podolia.

Korolivka is not far from Uładówka, where the estate of the Potocki family was located. It was there that Potocki spent his childhood and where he –stayed as an adult whenever he was not traveling. Uładówka was also the haven to which Potocki ‒ suffering from poor health and melancholia (as depression was called at the time)‒ retired in 1812. And where he committed suicide three years later.

Which brings us to his suicide once again. Was Potocki trying to say something with his death? Was he trying to teach Chołoniewski one last lesson? One he would never forget. According to Michał Otorowski this question must be asked in the larger context of the philosophical discussion between Potocki and Joseph de Maistre, a conservative Catholic thinker with whom Potocki became acquainted in Saint-Petersburg and with whom he corresponded until almost the end of his life. The debate between the two writers centered around issues of theosophy and the authority of the Catholic Church (a reflection which can be seen in the Manuscript, where de Maistre hides under the mask of the Theologist whereas Potocki is the Naturalist).

Like de Maistre, Chołoniewski was a proponent of absolute Catholic authority. What message could Potocki‒ a liberal agnostic and materialist ‒ have wanted to address to the young cleric? Was he, as Otorowski suggests tentatively, trying to cure his young friend from the fear of death? If that was the case, he chose a rather brutal solution – and the shock therapy didn't work. Chołoniewski became a priest and proponent of Catholic orthodoxy.

But, as the Polish scholar suggests, there's another reason why we will never learn the real motives behind the macabre events in Uładówka. This is because the most important element of the lesson proposed by Potocki may have been simply overlooked. Chołoniewski recounted that upon entering the room of the dead man, one could see on the count's desk some papers and books, but no sign of a last will or any other kind of document that could explain what had just happened. But he also remembered a rather small piece of paper left in a conspicuous place; on it one could see ’several caricatures of wild fantasy, sketched recently with a skillful hand.’ Were these drawings Potocki’s last message to the world?

Author: Mikołaj Gliński, 23 December 2015

Bibliography: Michał Otorowski "Jan Potocki: Koniec i początek" (2008), Michał Otorowski "Archipelag Potockiego" (2010)