Interwar period, 1918-1939

Pictorialism: Wilno, Lwów and Other Art Photography Centres

Although Wilno had a nineteenth century tradition of studio photography, it was only around 1908 that Jan Bułhak, later called "father of Polish photography", created works called fotografiki (Bułhak's term), inspired by the ideas of the painter Ferdynand Ruszczyc. These works can be considered art photography, both from a theoretical and artistic perspective. His books include Fotografika (Photography), Estetyka swiatła (The Aesthetics of Light) and Fotografia ojczysta (Photography of the Homeland). He was an excellent portraitist, and also recorded a place's architectural and spiritual climate, first in Wilno (1912-1919) and then in the 1920s and 1930s throughout Poland. He was especially sensitive to the contrast of light and shadow, working within the concept of photographic Impressionism, and consciously strove to approximate abstraction in his photographs. His ideal was "fotografia ojczysta" (photography of the homeland) which would promote national values. Thus, Bułhak combined the patriotic function of nineteenth century photography with the aesthetic postulates of the Parisian Photo Club, to which Benedykt Tyszkiewicz belonged. The Polish Photo Club, founded in 1930, was a private artistic organisation which brought together the leading Polish photographers. Bułhak, a member of this club, was also a lecturer at the Art Photography Section in the Department of Fine Arts of Stefan Batory University in Wilno during the years 1919-1939. He was a very influential figure in the world of Polish photography, even after the Second World War. Among those active in the Wilno Photo Club, founded in 1927, were Wojciech Buyko, Edmund and Bolesława Zdanowski, Kazimierz Lelewicz, Jan Kurusza-Worobiew, the theorist and publicist Father Piotr Śledziewski, Maria Panasewicz, Aleksander Zakrzewski, Napoleon Nałęcz-Moszczyński and, in Krzemieniec, Henryk Hermanowicz. That same year, the First International Photography Salon took place in Warsaw. In 1931, the Wileński Almanach Fotograficzny (Wilno Photographic Alamanac) was published based on exhibitions that had taken place from 1927 to 1930.

Jan Bułhak, "Gobelin letni (Wilno)", fotografia, 1930, fot. Arkadiusz Podstawka, dzięki uprzejmości Muzeum Narodowego we Wrocławiu

Jan Bułhak, "Gobelin letni (Wilno)", fotografia, 1930, fot. Arkadiusz Podstawka, dzięki uprzejmości Muzeum Narodowego we WrocławiuLwów was the second most important centre of Polish pictorialism. There was a strong tradition of studio photography in the city, which developed in opposition to pictorialism as a craft and documentary form. Lwów pictorialists found their inspiration in the works of famous Austrians, including Hans Watzek and Hugo Henenberg, and had institutional support in the form of the Lwów Polytechnic, where Mikolasch lectured at the Photography Section, and the University of Lwów, where Świtkowski taught. Other important artists of this group, who were all members of the Lwów Photographic Society (Lwówskie Towarzystwo Fotograficzne) included the chemist Witold Romer (who in 1936 invented the new technique for separating tones called "photographic isohelia"), associated with the Lwów Polytechnic, where he was director of the Photography Institute (1932-1939). He was also connected with the Atlas Book Dealers (1925-1939), publishers of photographic postcards by well-known Polish art photographers such as Jan Alojzy Neuman in the 1930s, which combined the isohelia technique with a modernist approach. In addition, they also published the works of Janina Mierzęcka. Franciszek Groer, whose interest in photography began before 1910, also belonged to this group. Of lesser importance were the photographic centres of Poznań, Warsaw and Kraków.

Representatives of the Poznan centre included Tadeusz Cyprian, active since 1913, who was a lawyer by profession. He first began as an expert of the Hucul region and a Symbolist, who in the 1930s allowed the use of small image cameras in art photography. He was the author of the book Fotografia: Technika i Technologia, which was reprinted many times. Another Poznan photographer was Bolesław Gardulski, formerly of Kraków, a portraitist and landscapist, who used the gum bichromate technique. Tadeusz Wański, known for his Romantic, nostalgic landscapes, was recognised after the Second World War as the best representative of Bułhak's legacy. Warsaw's Marian and Witold Dederko invented a new technique, called "photonite" (fotonit), which involves reworking the original photograph with inks and paints and then re-photographing the original, giving an expressionistic effect. Julian Mioduszewski was a portraitist and recorder of quotidian life, whose portraits included those of Włodzimierz Kirchner and Klemens Składanek. The former independence activist Edmund Osterloff, who lived in the Radom area, was also associated with this group. The Kraków photography scene was represented by members of the Polish Photo Club, Władysław Bogacki and Józef Kuczyński, whose studio photography reflected the tradition of Rzewuski, Józef Sebald and Szubert.

In the 1930s, using high quality techniques, pictorialists took photographs of street scenes ever more frequently, including depictions of workers, which just a few years earlier would have been impossible for programmatic reasons. Bulhak himself also took up modernist themes in the 1930s, as did Romer, for example, which were photographed in a very harsh way. Thus, pictorialism approximated, or rather adopted, some of the ideas that typified the "new photography", which it had rejected just a few years earlier.

It is worth nothing that Polish pictorialists maintained many contacts abroad, made possible by their participation in international photographic salons all over the world. Cyprian was a correspondent for the yearbook Photograms of the Year in Great Britain, while in Poland, the journals Fotograf / The Photographer and Miesięcznik Fotograficzny / The Photography Monthly were being published.

The Avantgarde and Modernism

Władysław Strzemiński, one of Kazimierz Malewicz's star pupils, was an important figure in the development of photography and avant-garde film during the interwar period. Interested in Unism, a Polish school of painting, and in subordinating creativity to utilitarianism, he did not see in photography a new, autonomous centre of avant-garde art, only insofar as it served the needs of graphic design. Other than the occasional exhibition, there was no real attempt made to keep in touch with the European artists involved in photography and avant-garde film.

Avant-garde photography was being done by artists in other fields, but Polish pictorialists and representatives of the classical avantgarde were completely isolated from each other. At first, the emphasis was on Constructivism, and later on Surrealism, though usually only dealt with in a superficial way. Photography was a modern weapon in the struggle for a new art, but also a form of political agitation, most often through photo montage.

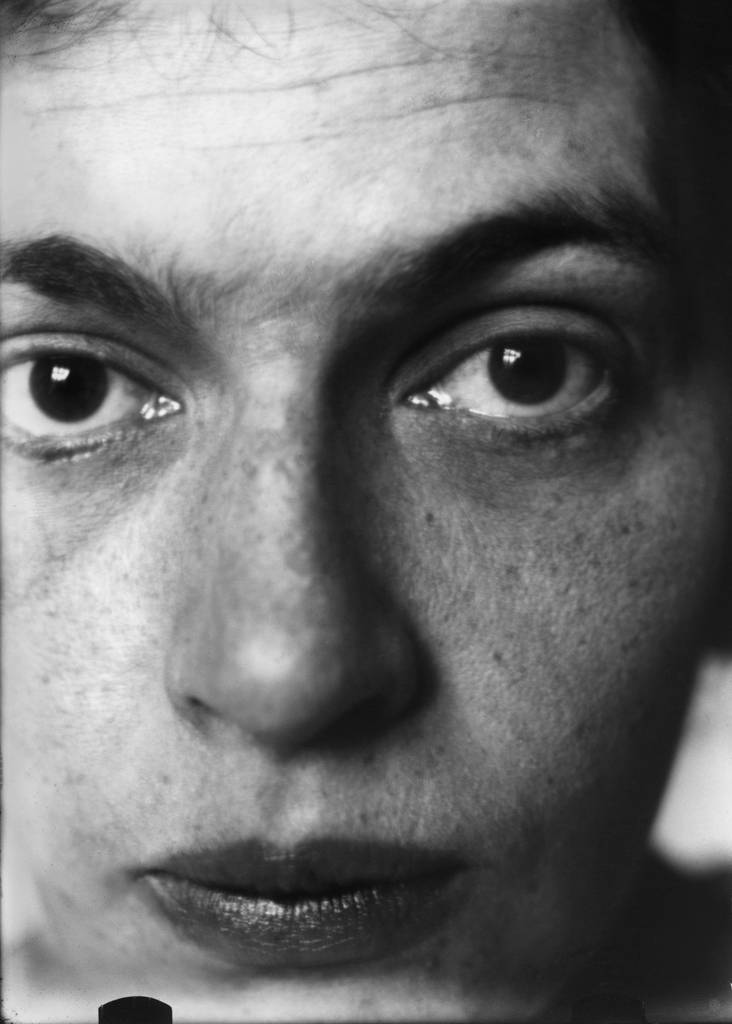

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, "Jadwiga

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, "Jadwiga

Witkiewiczowa", 1923, photo from the collection

of Ewa Franczak and Stefan Okołowicz,

The Wilanów Palace MuseumThe work of Witkacy (Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz) occupies a unique place in modernist photography. For this outstanding art theorist, playwright and unfulfilled painter, photography was a multi-functional instrument that allowed the artist to come to know one's own identity and personality better-or mask it. He abandoned landscape and pictorial photography for deeply psychological expressionist portraits and auto-portraits, and staged para-Dadaist scenes. His most valuable "close-ups" photographs were taken during the years 1912-1919.

Among those who created Constructivist, leftist-oriented photo montages, heralding a modern, optimistic civilisation, were Mieczysław Szczuka and Teresa Żarnowerówna of the Blok group and Mieczysław Berman, who in the 1930s found inspiration in works by the former Dadaist, John Heatfield. Mieczysław Choynowski and Władysław Daszewski's photo montages also fall into this group of activities. Kazimierz Podsadecki and Janusz Maria Brzeski were at first were linked to the Kraków group Zwrotnica, and then to Strzemiński's group; the work of these two men, who were also active in graphic design, had a more commercial slant to it, and was influenced by the grotesque and even caricature. Their photo montages (photo collages) were unique. In 1932, they founded the Polish Avant-Garde Film Studio in Kraków, but it was only Brzeski who was interested in the modernist possibilities that photography opened up, from its uses in the press, to "new photography" shots, and photograms (photographs without negatives), including negative photo montage, and experimental film. (No copies have been preserved of Brzeski's 1933 film Beton (Cement)). They had an anti-mechanical attitude, criticising the latest trends in Western and American civilisation in a dadaistically constructivist fashion, taking into account the role of eroticism, which can be seen as an ironic interpretation of the psychoanalytical theories of Sigmund Freud popular at the time.

The painter Karol Hiller belonged to the lodZ group "a.r.", and developed his own technique, "heliographics", in the 1920s. This technique, which he believed to be a new graphic technique and not ordinary photography, was a variation of the rarely-used graphics technique cliché verre, similar to that employed by Bruno Schulz. Hiller based his works on small drawings reminiscent of a film strip in several other conventions, ranging from organic abstraction, which can be seen as a precursor to the material painting of the 1950s, to the constructivist influences of the Bauhaus school, which in the late 1930s took the place of catastrophism and even that of new classicism of religious iconography. Thus, he is an example of a modern artist who was not tied to just one convention and technique, but rather one expressing doubt regarding the postulates voiced by proponents of the avantgarde, reflecting the mood of the art world not only in Poland, but in Europe as a whole in the late 1930s.

Stefan and Franciszka Themerson, in addition to their literary interests, made surrealistic photo montages and abstract photograms for seven experimental films, including Europa (1932), which has not survived. Photographic materials were combined with motion film footage. In the 1920s and 1930s, the European avantgarde, including Polish artists, began to experiment in photography and film. Themerson was also the editor of the journal f.a. (Film artystyczny / Artistic Film).

Among the most interesting accomplishments of this period include the photography of Aleksadner Krzywobłocki, a member of the Lwów "artes" group, which had been active since the late 1920s, first in Constructivism, then in a variously-but most often superficially-interpreted super-realism (for example the photo collages of Margit Sielska and Jerzy Janisch). In Krzywobłocki's photographs one can see serious and original signs of his interest in Surrealism - from psychological portraits with mirrors, to dream-like visions (S.O.S., 1929) to games like photo performances, sometimes using theatrical props. As a result, he is, just like Witkacy, a precursor of the "staged photography" of the 1980's and 1990's. It should be noted that "new photography" virtually did not exist in Poland, where few artists were aware of the possibilities presented by modernist photography, including the "straight" variety. Writer and photographer Antoni Wieczorek, specialising in industrial and mountain themes, was one of the few supporters of the new trends.

Documentary photography

The pictorialists did not consider documentary photography to be art. This kind of photography was done from the late 1920s on with small cameras, such as the Leica. Sharp-image lenses were used. In Poland, however, for various reasons this kind of photography did not develop as it did in Germany or Czechoslovakia. In Poland, documentary photography took two forms. The first was geared toward the press at that time, for high-circulation publications. It presented political events in their social context (Jan Ryś and Henryk Śmigacz of "Kurier Warszawski" / "Warsaw Courier"). The second was not intended for mass audiences, but rather existed only as part of a photographer’s oeuvre. Aleksander Minorski's photographs from the 1930s documenting the life of Warsaw's poor were an exception to this. Roman Vishniak of Warsaw took portraits of Polish Jews in the late 1930s; Mojżesz Worobieczyk did the same in Wilno. Stefan Kielsznia's photographs of Jewish shop display windows in Lublin's Old Town, done as a document for the historical preservation official, complement Worobieczyk and Vishniak's photographs. Kielsznia's photographs are the most varied in terms of photographic material used. In addition, there was also the series titled Kazimierz nad Wisłą by the well known Warsaw portrait photographer Benedykt Dorys. The series was displayed for the first time in the 1960s. The studio photographer Józef Szymańczyk took photographs of the Polish Kresy - former Eastern lands of Poland before 1939 - from the Kosów Poleski region in the spirit of Bułhak's "photographs of the homeland" program; in addition, he also took photographs documenting poverty. Tadeusz Rydet took interesting photo-journalism shots of the Polish army in the 1930s.

The most important show of documentary photography with leftist leanings was the First Workers' Photographic Exhibition, organised in Lwów in 1936. There, harbingers of social photography were visible, as well as of the socialist-realist photography of the early 1950s (such as the work of E. Zdanowski and Władysław Bednarczuk).

Communist Period (1945-1989)

Time of expectation (1945 -1948)

The period of the Second World War caused uncounted losses to Polish culture, including photography. The most important Polish war photographers were J. Ryś and H. Śmigacz, who recorded the September 1939 campaign in the capital, and the photographers of the Warsaw Uprising - Tadeusz Bukowski, Sylwester Braun and Eugeniusz Lokajski, who took the famous shot of the wedding of a man and woman who were both fighting in the Warsaw Uprising.

After the war, there was hope that a democratic state and its organisational structures would be renewed. In 1946, the National Museum in Warsaw held an exhibition of Bułhak's photographs titled Ruiny Warszawy / The Ruins of Warsaw. In 1947, at the initiative of Bułhak and Leonard Sempoliński, the Polish Union of Art Photographers (Polski Związek Artystów Fotografów) was founded, in 1952 renamed the Union of Polish Photographic Artists (Związek Polskich Artystów Fotografików), which continues to exist today. It continued in the tradition of the Polish Photo-Club in terms of its concept of art photography, though it was adapted to the reality of life in a socialist state, whose political directives affected photography as well.

On the one hand, pictorialism was continued (Bułhak, Mierzecka, Wański), which was adopted quickly to the needs of state propaganda in the form of socialist realism. On the other hand, the photographic avantgarde experienced a renaissance. The painter Zbigniew Dłubak was the most important artist in this field until late 1981, using both photography and painting equally in his work. He inspired an exhibition titled Modern Polish Art Photography (1948), in which the following photographers, in addition to Bułhak himself, took part: the prewar pictorialist, Edward Hartwig, Sempoliński and Fortunata Obrąpalska. Except for Bułhak, all had participated in the Modern Art Exhibition in Kraków in late 1948 and early 1949. It was the first interdisciplinary show in Poland at which photography tending toward Surrealism and abstraction received equal treatment.

Socialist Realism (1948 - ca. 1955)

Although any experimentation in artistic work was forbidden, including in the field of photography, photography held a very important place in the framework of "socialist culture". In Świat Fotografii / The World of Photography and then in Fotografia / Photography (edited from 1953 to 1972 by Dłubak), there were discussions of what "socialist realist photography" should be. Within socialist realism, there were three trends: classical, pictorial and documentary, which were represented, for example, by Hermanowicz, Hartwig, Obrąpalska and Jerzy Strumiński.

The Avantgarde in Photography, late 1950's - 1981

In the late 1950's, an informal group was formed whose members included Zdzisław Beksiński (who was also an abstract painter), Jerzy Lewczyński and Bronisław Schlabs (also a fabric painter). They experimented in various ways, alluding to the work of the interwar avantgarde. Of these, Beksiński's works were the most innovative: reminiscent of interwar Surrealism, he used amateur photographs and destroyed negatives in them. He created untitled series of a proto-Conceptualist and Expressionist nature, anticipating artistic trends such as photo-performance and body-art. Lewczyński worked in a similar mode, concentrating since the 1960s on a multifaceted use of "found photography", creating a program over the years that was later called "photographic archaeology". Schlabs, on the other hand, believed that future art would be of an abstract nature, which is why almost all of his work was a mix of photography, graphics and painting. This informal group's most important show was a closed exhibition at the Gliwice Photographic Society in 1959, titled Anti-Photography. Dłubak challenged their views and approach to photography, arguing that photography must be based in the principles of the medium, which are connected with the qualities of photographic materials. He expressed these ideas in a series titled Egzystencje / Existences, (1959-1966), whose form approximated Nowa Rzeczowość / New Practicality.

The Kraków Group was also active in the late 1950s. Marek Piasecki's miniatures reflected the legacy of expressive abstract painting; he also created Surrealistic compositions with dolls. Except for his Genesis series from the late 1960s that was in a religious (albeit experimental) vein, Andrzej Pawłowski always emphasised the fundamental importance of light as that which constructs a biological image as the reflection of the fragmentary of its body and the developing principle of the photogram as a study of the structure of form.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, Edward Hartwig developed a special graphics-like style that was part pictorial, part modern, as can be seen in the album Fotografika / Photography. Hartwig's concept influenced many other Polish photographers, particularly in the field of landscape photography.

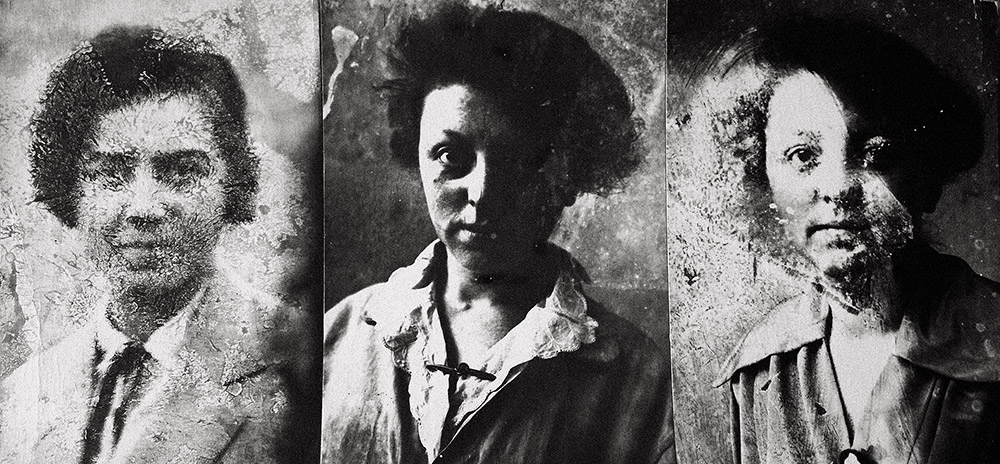

Jerzy Lewczyński, "Tryptyk znaleziony na strychu", 1971, from the collection of the Museum in Gliwice

Jerzy Lewczyński, "Tryptyk znaleziony na strychu", 1971, from the collection of the Museum in GliwiceIn the 1960s, the avantgarde weakened as photojournalism and press photography developed, influenced by the international success of Edward Steichen's exhibition, The Family of Man, which was shown in Warsaw in 1959. The Zero 61 group in Toruń mixed various ideas of modernity, interpreted as an experiment, with pictorialism, all the way to Symbolist painting. This group included Czesław Kuchta, Jerzy Wardak, Józef Robakowski, Andrzej Różycki, Antoni Mikołajczyk and Wojciech Bruszewski. Their road from art photography to increasingly progressive concepts was a long one, and toward the end of the group's existence they experimented with a mix of Dadaism and pop-art. The exhibits at their untitled exhibition in an old blacksmith shop in 1969, for example, were slated to be destroyed afterwards.

A breakthrough in Polish photography came between the years 1968, when the Exhibition of Subjective Photography took place, and 1971, the year of the exhibition titled Photographers' Quest / Fotografowie poszukujący, when many artists, under the influence of pop-art and the general dematerialisation of art, moved to photomedia in the fields of experimental film, photography and video.

In the 1970s, analytical photography, called "photomedialism", was the dominant mode. The Łódź group Warsztat Formy Filmowej (Film Form Workshop) (1971-79), which included former members of the group Zero 61, was active in this field (Robakowski, Bruszewski, Różycki and Mikołajczyk), as well as new members (Ryszard Waśko, Paweł Kwiek and Zbigniew Bruszewski). They conducted various structural experiments that studied the nature of photography as a medium, and its formal possibitilies in terms of its relationship to other avant-garde forms such as performance art. At the same time, they revealed the limits of ideas stemming from film and photography concepts and Conceptualism, which was the foundation for the most significant para-scientific analyses. Wroclaw was another photomedialism centre, home to the Permafo group (1970-1980), to which Dłubak belonged, as well as Andrzej and Natalia Lachowicz, who later used the pseudonym Natalia LL. She created her most important works in the 1970s, shifting over to feminist art, then drew closer to Existentialism, with religious subtexts, in the 1980s. In the late 1970s, the Seminarium Foto-Medium-Art also was active in a Wrocław gallery by that same name, with the encouragement of the photography theorist and critic Jerzy Olek.

Also active at that time was the Warsaw Seminar (Seminarium Warszawskie), which included Dłubak's students from the Łódź Academy of Fine Arts. The Seminar's theoretical underpinnings, which for it were more important than their practical application, brought it close to a concept of Postmodernism having its roots in late Structuralism.

The imposition of martial law brought an end to Polish photomedialism, whose last significant show was in Łódź, titled Construction in Process / Konstrukcja w procesie (1981). In 1980 and 1981, Constructivism, Minimal art, Conceptualism and photo-performance, which had all been advocated by the Polish neo-avantgarde, were subjected to serious questioning, and even attacked in Dadaist performances by the Łódź Kaliska group, founded in 1979. This group's members included Marek Janiak, Andrzej Kwietniewski, Adam Rzepecki, Andrzej Świetlik and Makary (Andrzej Wielogórski).

Other artists active during the 1970s significant from the analytical point of view included Janusz Bąkowski (whose works were quasi-mathematical and systematic), Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, who cast doubt on photographic realism; the poetic Andrzej Dłużniewski, who linked Conceptualism with the reductionism of Leszek Brogowski, an art historian, critic and artist (Idiomy series), Ireneusz Pierzgalski (spatial arrangements with slide projections); Grzegorz Kowalski (body art). Some-the exceptions-were already questioning mass media's credibility (Zygmunt Rytka and Zdzisław Sosnowski). Mariusz Hermanowicz was at the fringe of the neo-avantgarde. In his original, sarcastically ironic works, Hermanowicz commented on the grey reality of everyday life in communist Poland; later, he continued his work abroad. Martial law brought about the closure of many galleries, and many photographers and other artists who used photographic techniques in their work emigrated at this time.

Documentary Photography and Photojournalism, 1950s - 1981

In 1951, the weekly Świat / World was founded, whose contributors included Wiesław Prażuch, Jan Kosidowski, Władysław Sławny and Konstanty Jarochowski. Swiat was published until 1969, and was based on the experiences of the Magnum group, founded in 1947, and also on those of French photography of that same period, which at that time was focusing on humanistic photo reporting. Another important publication was the monthly Polska / Poland, notable also because it was among the first publications to publish colour photographs. Polska's contributors included Tadeusz Rolke and the portraitists Marek Holzman and Eustachy Kossakowski. Photography also played an important role in Przekrój, one of Poland's most popular cultural titles, whose contributors included Wojciech Plewiński, as well as Kultura, which published Aleksander Jałosiński's work. Adam Bujak's works documenting religious life are unusual for a number of reasons. He worked as a photographer from the 1960s to the present, drawing on the "homeland photography" and landscape concepts of the Kielce Landscape School (Kielecka Szkola Krajobrazu), to which Paweł Pierściński belonged. Other photographers were also influential in this school, including Hartwig. The tradition of bold photo reporting was taken up later by the student weekly ITD (And So On), whose contributors included Sławek (Bogusław) Biegański.

The photographers associated with these publications, and also with Razem / Together and Perspektywy / Perspectives, were of course functioning in the context of a socialist system, but were critical of Edward Gierek's "propaganda of success". Krzysztof Paweł was one of the leading photo reporters of the 1980s. In 1980, the work that had been done up to that points in this photographic genre was summed up in Bielsko-Biala at a large event made up of eight separate exhibitions titled Polish Sociological Photography Review.

The exhibitions organised after the strikes and the registration of the Solidarity trade union in 1980 were very popular with all levels of society. The works of Witold Górka, Stanisław Markowski and B. Biegański were shown. The dramatic photographs taken by Bogusław Nieznalski during martial law are particularly striking. Krzysztof Gierałtowski, who was working for ITD, distinguished himself as the best portraitist of the 1970s and 1980s, and he has continued to work in this genre. His portraits, expressionist and pictorial in style, have captured the luminaries of Polish cultural life on film in a very unusual way.

A series done by Zofia Rydet in the 1970s and 1980s was also very important, not only in terms of the concept of "sociological photography", but also for Polish photography as a whole. This sociological record presented the face of Polish society, just as August Sander had done in Germany during the first decades of the twentieth century. Rydet was particularly sensitive to the image of religious Polish villages, often wretchedly poor. In the late 1970s, Krzysztof Pruszkowski's work was a cross between documentary photography and more progressive trends. In the 1980s and 1990s, this photographer developed the visual concept of "photosynthesis", a multiple exposure technique that creates a graphics-like effect.

Zofia Rydet, "Zapowiedź jutra / Preview of tomorrow", 1959, photo by courtesy of Asymetria Gallery

Zofia Rydet, "Zapowiedź jutra / Preview of tomorrow", 1959, photo by courtesy of Asymetria GalleryThe 1980s, Martial Law and Its Consequences for Photography

After the shock of martial law, imposed on 13 December 1981, Polish culture went underground. After 1984, cultural life gradually revived. In 1989, a new period began following the elections, the formation of Tadeusz Mazowiecki's government and the lifting of censorship. This period was characterised by the departure from socialist centralism and a move to a liberal state. Connected with this was the collapse in 1991 of the Federation of Amateur Photographic Societies and the artistic marginalisation of ZPAF, which was particularly apparent over the next ten years.

The first movement to take up the struggle against the state that imposed martial law was "at the Church's side" - ironically called "art in the vestibule". This movement, as the name suggests, organised exhibitions in the churches of major cities throughout Poland. Photography and photographers played an important role in these exhibitions, and included Mariusz (Andrzej) Wieczorkowski (one of Poland's most intriguing photographers who at that time was still unknown), Paweł Kwiek, Zofia Rydet, Erazm Ciołek and Anna Beata Bohdziewicz. Since the 1980s, Bohdziewicz has kept a Fotodziennik (Photojournal) - a record of events private and public that has been shown at many exhibitions both in Poland and abroad.

Another, smaller underground movement called Kultura Zrzuty (Collective Culture) developed with neo-avantgarde origins primarily in Łódź. At first, this group continued the photomedia tradition, adding to it certain Dadaist forms. In addition to the group Łódź Kaliska, other artists who were active in this movement included J. Robakowski, Z. Rytka and Grzegorz Zygier. In addition, young intermedia artists like Jerzy Truszkowski and Zbigniew Libera were also involved. A. Rozycki and P. Kwiek already at that time were in search of the sphere of the sacrum, although they were active in a milieu in which nihilistic artistic views were dominant. Beginning in the early 1980s, there was one more movement called "elementary photography", which built on the experiences of Conceptualism (Jerzy Olek) and the Czechoslovak and American Modernist traditions (Andrzej J. Lech, Bogdan Konopka, Wojciech Zawadzki), and which was the equivalent of "visualism" in German photography (Andreas Müller-Pohle). There were many interesting photographers connected with the trend called "staged photography" that was gaining force in the 1990s. These included Janusz Leśniak, Mikołaj Smoczyński and Grzegorz Przyborek.

Zofia Kulik, "Ja, maki i żart/Zofia Kulik, "I, poppies and joke" (from the series Mandala) B&W photography, consisting of repeatedly irradiated prints, 50 x 50 cm, edition: 2/1, 1992, photo by Zofia Kulik, Copywright Zofia Kulik and the National Museum in Gdańsk

Zofia Kulik, "Ja, maki i żart/Zofia Kulik, "I, poppies and joke" (from the series Mandala) B&W photography, consisting of repeatedly irradiated prints, 50 x 50 cm, edition: 2/1, 1992, photo by Zofia Kulik, Copywright Zofia Kulik and the National Museum in GdańskIn addition to these dominant trends of the late 1980s, there was also the very original feminist work of Zofia Kulik, which was a kind of settling of accounts with the communist past and her own personal life. Marek Gardulski and Wojciech Prażmowski's work in a novel way built on the concept of family photography, anonymous and destroyed, which had already been seen in Lewczyński's work from the 1960s. Also worth noting is Tomasz Tomaszewski's multifaceted documentation, in colour photography, of the last Polish Jews, titled Ostatni (The Last Ones); Tomaszewski has also worked for National Geographic. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, there were also exhibitions of Ryszard Horowitz's work in Poland. These revealed the issues related to digital photography and Postmodernism in art, very important problems from both the technological and theoretical perspectives.