Works dedicated to Polish and Ukrainian war often feature the motif of an almost ritual offering of innocent youngsters sent into carnage. This is the case in the short book by Juliusz German dedicated to a brave ten-year-old boy O Janku, Co Walczył we Lwowie (About Janek, Who Fought in Lviv) or in the poem by Henryk Zbierzchowski ‘O Antosiu Petrykiewiczu’ (About Antoni Petrykiewicz), about a thirteen-year-old who was lethally wounded on Lviv’s Executioner’s Hill, the youngest ever cavalier of the War Order of Virtuti Militari.

In memory of the little soldier

who saved Lviv

for Poland’s glory

Helena Zakrzewska in her short story Lulu from a 1919 book of short stories entitled Dzieci Lwowa (Children of Lviv) presented war as seen from the perspective of a child. The main character is from a well-to-do and loving family, but the events of 1914 put a stop to his idyllic life. His father becomes a soldier and his mother is killed by the Kozaks: ‘she went to God to pray for father’.

Lulu wanders about homeless and hungry: a poor peasant family who takes him in, sells him to a Russian soldier who misses his children while in the trenches, and wants to raise him to be a Muscovite soldier. Lulu gets used to life on the front, spends time building fences from sticks and bombarding them with pine cones. However, the war deprives him of yet another guardian. Afraid of ‘the Austrians, who eat children’, he hides in the forest, then in a convent, and later he joins a gang of war orphans, to finally find his father during a triumphant parade of Polish soldiers in town.

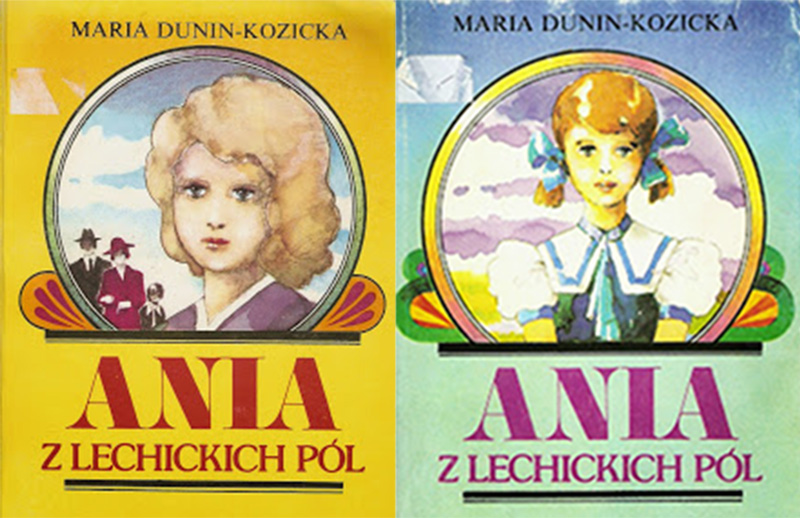

Ania z Lechickich Pól (Ania of the Polish Fields) by Maria Dunin-Kozicka, rep. Dagmara Smolna

The Eastern borderland conflicts are also depicted in books for girls. The Ukrainian rebellion and the October Revolution had an impact on Ania z Lechickich Pól (Ania of the Polish Fields) by Maria Dunin-Kozicka. This three volume saga for girls (Childhood, Youth and Ania’s Love) was regarded as a Polish response to Anne of Green Gables.

The Polish Anne was a paragon of feminine virtues – beautiful (of course with fair hair and blue eyes), kind to other people and clever. However, the description of political and social background is what makes the book different from typical novels for school girls. In the following fragment, revolutionary turmoil is confronted with the myth of civilising the gentry in the East.

The rural community, tempted by a programme which promised to change to ‘all, all, all’ into prosperity and happiness, was very willing to listen to the political preaching. The attitude towards the gentry was changed fiercely, however, like in a distorting mirror. The most civilised establishments of ‘the rulers’ were destroyed. (…) People destroyed a brick hut housing ‘a little bank’ established by Mr Alfred for peasants in order to fight with the Jewish usury.

All of the above mentioned themes were highlighted in the 1922 book Białe Róże: Powieść dla Młodzieży z Czasów Inwazji Bolszewickiej (White Roses: A Novel for Youth from the Time of the Bolshevik Invasion) by Helena Zakrzewska. Other than telling the story of the main characters, the book describes the ethos of the scouts’ and the gentry.

Two siblings – Janek and Wandzia, are orphans raised by their aunts. They were raised as patriots and, when Poland faces a communist invasion, they are happy to do something for their homeland. Wandzia helps out as a courier, Janek, as a scout helps as a telegraph operator. The younger and more carefree (albeit no less brave and courageous) Janek treats the whole ordeal like an adventure at summer camp.

This will be a wonderful journey! (…) Do you remember us playing all day when we were small? I would travel far for the crusades, and you, brave lady, would take a ribbon from your French braid and attach it to my helmet. Now we will really do what we once just pretended.