Almost completely destroyed in World War II, Warsaw’s Old Town was rebuilt under the architectural supervision of Prof. Jan Zachwatowicz. His recreation of the Old Town is widely considered a spectacular success, with a UNESCO certification to boot, even though it isn’t always entirely faithful to the pre-war original – educated improvements were introduced where possible, and many who remembered the original said it didn’t quite feel like the original, and was somehow off. As shown by the buildings discussed below, it seems the Old Town would become an omen for Warsaw, the city where reconstructions of the past have become a local tradition.

Rotunda

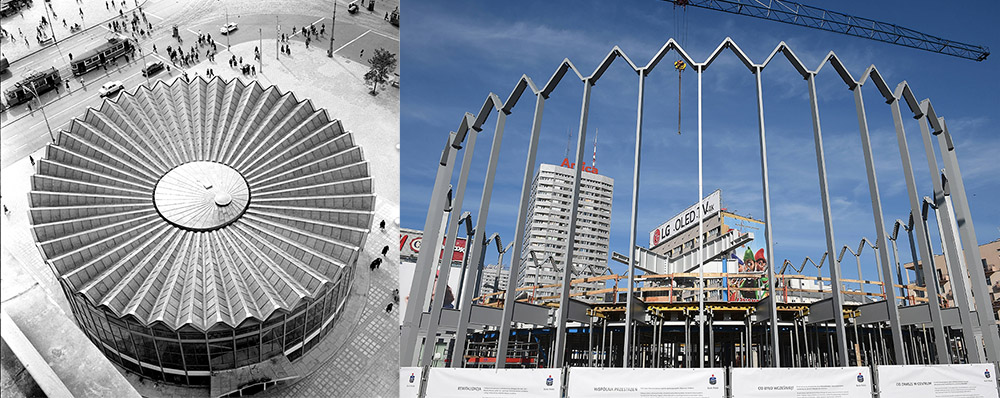

The Rotunda building, 1966, Warsaw, photo: Lucjan Fogiel/Forum. The construction of the new Rotunda in Warsaw, 2018, photo: Radek Pietruszka/PAP

The Rotunda building, 1966, Warsaw, photo: Lucjan Fogiel/Forum. The construction of the new Rotunda in Warsaw, 2018, photo: Radek Pietruszka/PAPFor many years the Rotunda, a 1966 bank building designed by Jerzy Jakubowicz, was among the most characteristic structures of the capital. Due to its intriguing modernist shape, the zig-zag line of the roof bringing to mind a Polish general’s braid, it was affectionately called ‘the general’s cap’. Located in one of the city centre’s busiest spots, the Roman Dmowski roundabout, it was much more than just a place for bank services – it served as an orientation point for tourists as well as a meeting point for locals. Meeting up in front of the Rotunda was a Warsaw staple.

Today the building is being reconstructed from the ground up (neither its steel framework nor the foundations were left intact) according to a design by the Gowin & Siuta architectural bureau. Even though the new Rotunda will closely mimic its original, some Varsovians see this as an act of heritage destruction, arguing that the unique modernist structure should’ve been preserved rather than re-created. Those who are in favour of the revamping argue that the building was in bad shape and required a lot of work anyhow and that it’ll also receive a valuable addition: a public area on the first floor, that will possibly feature a coffee house, information point or art gallery (though this hasn’t been finalised yet). The construction is planned to be through by the end of 2018 and it seems only then, after everybody has seen the effects, will it really transpire whether the decision to redo this Warsaw landmark was a sound one.

Jabłonowski Palace

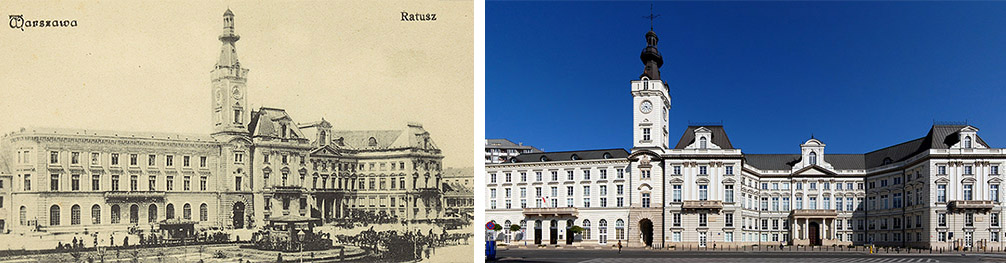

The Jabłonowski Palace, Warsaw, before the year 1913, photo: BP Polona. The Jabłonowski Palace in Warsaw’s Theatre Square, 2009, photo: Marcin Białek/wikimedia.org

The Jabłonowski Palace, Warsaw, before the year 1913, photo: BP Polona. The Jabłonowski Palace in Warsaw’s Theatre Square, 2009, photo: Marcin Białek/wikimedia.orgThe Jabłonowski Palace, prestigiously located vis-a-vis the National Theatre in Warsaw’s Theatre Square, is another bank building that’s been reconstructed, although its story is very different from that of the Rotunda. Originally raised toward the end of the 18th century for the aristocrat Antoni Barnaba Jabłonowski according to a design by Jakub Fontana and Dominik Merlini, the building was later adapted to serve as City Hall and given a neo-renaissance look. This was all destroyed during World War II and until the 1990s only the famous Monument to the Heroes of Warsaw 1939-1945 or The Warsaw Nike by Marian Konieczny, unveiled in 1964, stood in its place.

Eventually the monument was moved to a nearby location and the palace rebuilt in 1997 according to a design by Leszek Klajnert, in a form strongly resembling the pre-war one. But the semblance is noticeable only in the exterior – the interiors have modernised to best serve as office space. If you look closely from the outside, you’ll even see storey lines crossing the tall, old-school windows… Although some Varsovians disliked this approach, arguing that the result is a mere ‘simulacrum’, others appreciated the restoration of the historical outline of the square. The website Place Warszawy, which writes about the history and current condition of Warsaw’s squares, says of Jabłonowski Palace (and another Warsaw building designed by Klajnert to resemble historical architecture):

It’s not an attempt to deceive, you don’t have to believe that this is pre-war architecture – it’s plain to see that this is a game, a comedy of errors. (…) And that’s great! There’s a theatre here, nothing in this place should be as it seems at first glance.

Business with Heritage

The former tenement house in 1 Podwale Street, 2013, Warsaw, photo: Jacek Turczyk/PAP. The Business with Heritage office building raised in its place, 2016, Warsaw.

The former tenement house in 1 Podwale Street, 2013, Warsaw, photo: Jacek Turczyk/PAP. The Business with Heritage office building raised in its place, 2016, Warsaw.The idea to re-build a structure altering some if its features has been taken to the extreme by one of Warsaw’s most controversial architectural designs, the RKW Rhode Kellermann Wawrowsky bureau’s Business with Heritage. This office building was raised in 2015 in the historical Castle Square, where it has a prominent position with a direct view of the Royal Castle, once the seat of Polish kings. It took up the space of a parking lot and an existing tenement house that had been built in the 1980s to mimic classical architecture. The old building complimented the local urban landscape or Warsaw’s Old Town which itself is a reconstruction, as discussed above.

Even though the creators of Business with Heritage declared that their project will only ‘entail a reconstruction and adaptation of the already existing structure’ (as reported by the Archirama website) they eventually brought about a situation where ‘only a hollow shell remained that had been gobbled up by the office building’s construction’ as stated by the Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper. The resulting building has basically nothing in common with its original and introduces a polished style that may seem alien to an area striving to create a historical ambience. Many see this development as disappointing.

Those who appreciate Business with Heritage will argue that if everything around it is but a re-creation then why not have a re-creation that’s better, bigger, and more functional?

Hala Koszyki

The Koszyki Hall shortly before completion, 1908, image by R. Marcinkowski, taken from Atlas Dawnej Warszawy or The Atlas of Old Warsaw, photo: wikipedia.org. The Koszyki Hall in 2016, photo: Wojciech Kryński/Forum

The Koszyki Hall shortly before completion, 1908, image by R. Marcinkowski, taken from Atlas Dawnej Warszawy or The Atlas of Old Warsaw, photo: wikipedia.org. The Koszyki Hall in 2016, photo: Wojciech Kryński/ForumThe Art Nouveau Koszyki Market Hall designed by Juliusz Dzierżanowski and embellished with sculptures by Zygmunt Otto (e.g. of floral motifs and the Warsaw Mermaid) was erected in Koszykowa Street in 1908. It became a major source of foods for the local community but was destroyed in World War II. Rebuilt thereafter, it was declared a monument in the 1960s and continued to be an important shopping spot. In 2006 a reconstruction started, causing many concerns among architecture-conscious people as to how it will affect the building.

Due to troubles on the real-estate market, the renovation took far longer than expected and was completed as late as 2016. What appeared after a decade’s wait indeed resembles the original in shape but includes many elements that are new (most drastically the elegant window fronts in the courtyard and an underground parking lot). In an interview for the monthly Architektura & Biznes, the designers of the new Koszyki Hall, the JEMS Architekci bureau, call this approach a ‘natural, critical continuation’. They remind us that, due to Dzierżanowski’s vision not having been realised in full, the pre-war structure wasn’t as impressive as many people are inclined to believe, and also that the hall wasn’t rebuilt to the highest of standards after the war. Therefore, they say, sticking too closely to one of these ‘originals’ would’ve simply been misguided.

Some welcome the hall’s change (which also affected its profile: no more fish and vegetable stands, but instead bars and restaurants), while others frown upon it. But the new hall has undisputedly become a Warsaw hot spot with no shortage of visitors. They spend their time among certain preserved elements of the original construction like the tiles in the corridors and the original pre-war bricks. Most notably enjoyed are the side entrances with Otto’s sculptures: a bull’s head once symbolising that meat stands operated on the premises, and the Warsaw Mermaid, a sign that the hall used to be owned by city hall. In his book Korzenie Miasta (The City’s Roots) written towards the end of the 20th century, the journalist Jerzy Kasprzycki writes of the Koszyki’s embellishments:

The bull is beautiful, realistic, so appetising that it makes me want to kiss its velvet nostrils.

Elektrownia Powiśle

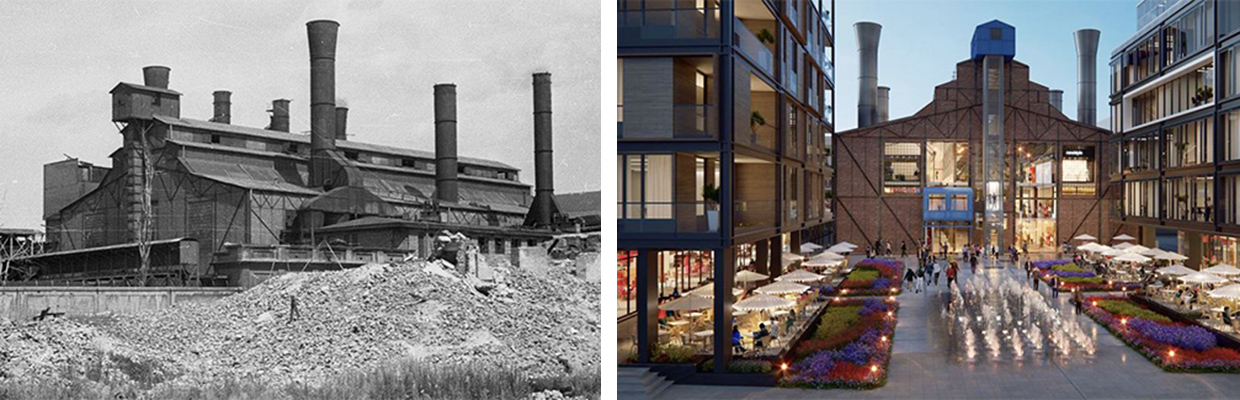

The Powiśle Power Plant in Warsaw. A visualisation of the reconstructed Powiśle Power Plant, photo: press materials

The Powiśle Power Plant in Warsaw. A visualisation of the reconstructed Powiśle Power Plant, photo: press materialsAn ongoing reconstruction sometimes compared to the Koszyki Market Hall is the one being done on the defunct power plant in Warsaw’s trendy Powiśle neighbourhood. Built in the early 20th century, the Powiśle Power Plant was damaged during World War II but some of the complex’s buildings miraculously managed to survive despite the heavy fighting that occurred on its grounds (as a stronghold of the Warsaw Uprising insurgents, it was subject to bombardment). After the war, the damaged plant was rebuilt and kept providing Warsaw with power until 2001 when it shut down. Three years later, it was declared a monument.

Last year, reconstruction commenced using a design by the APA Wojciechowski bureau. The vast post-industrial area (close to 28,000 square metres), favourably located near the River Vistula and a metro station, will be transformed into a multi-purpose hub with restaurants, coffee houses, bars, shops, boutiques, offices, apartments and a hotel. Some of this will be located in revitalised historical buildings and some in newly-built ones. An amazing turn of fate for a place that saw some of the most dramatic episodes in Warsaw’s history.

Lately, however, a picture of the reconstruction of the historical Boiler House No. 2 surfaced causing some concerns whether the extent of the work actually corresponds to the term ‘revitalisation’. In the picture you can see basically nothing but the original steel construction. There are no bricks, no walls. Some call this a mock-up of a monument in the making. Still, the developers declare that the reconstructed Boiler House will be as similar to its pre-war original as possible and that the revitalised complex will include many original elements like old floors and industrial equipment. The new plant is scheduled to be ready at the turn of 2019.

Kamienica Pawłowiczów

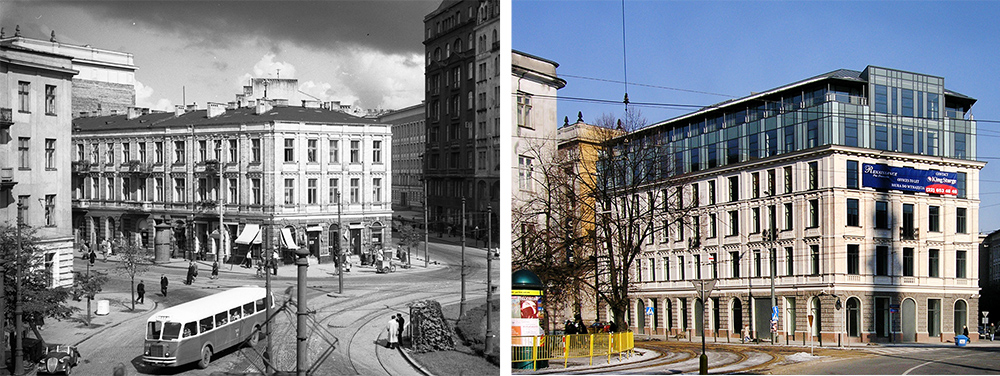

The Pawłowicz House in Plac Zbawiciela square, 1957, photo: Zbyszko Siemaszko/Forum. The Renaissance building, 2016, photo: Krzysztof Chojnacki/East News

The Pawłowicz House in Plac Zbawiciela square, 1957, photo: Zbyszko Siemaszko/Forum. The Renaissance building, 2016, photo: Krzysztof Chojnacki/East NewsTo fully understand why many Varsovians contest the extensive reconstruction of historical buildings one has to realise how heinously World War II affected their city: due to the conflict, around 85% of Warsaw’s buildings were destroyed. Those few buildings that actually survived are often cherished like relics. It’s unsurprising that the capital’s voices against making ‘mock-ups of monuments’ tend to be loud ones.

An example of a reconstruction that stirred a lot of controversy back when it was being done is the Renaissance office building completed in 2005. Raised in the Plac Zbawiciela square, a trendy downtown spot full of cafes, restaurants and traffic, the building stands in place of a tenement house called the Pawłowicz House (after the surname of its owners). Built toward the end of the 19th century and designed by Teofil Lembke, the ornate neo-renaissance building managed to partially survive the war. After being renovated, it stood in the square until the 2000s, when it underwent reconstruction. Here’s how the Warszawa 1939 website, devoted to the history of Warsaw’s architecture, describes it:

Under the pretext of construction work (adding new storeys, reshaping the interiors while retaining the exteriors) the house, amidst a scandal, was partially demolished in February 2002. In January 2003 it was demolished completely – only the front walls in Mokotowska Street and in the Square were left. In 2005 the reconstructed building was completed – the house gained a third storey, but over it two additional ones were built, with full-glass exteriors. Also the historical balconies, that had been preserved, were torn down.

It ought to be said, however, that the Renaissance building does a good job at mimicking historical architecture and doesn’t really seem alien to the square’s outline. Some see the design by Jean-Jacques Ory as a successful reinterpretation of tradition, one that harmonises with its surroundings.

CDT

The CDT Department Store, 1963, Warsaw, photo: Zbyszko Siemaszko/Forum. The reconstruction of CDT, a visualisation from 2017, photo: Immobel Poland

The CDT Department Store, 1963, Warsaw, photo: Zbyszko Siemaszko/Forum. The reconstruction of CDT, a visualisation from 2017, photo: Immobel PolandConcerns very similar to the ones presented above were (and still are) raised in the case of the almost ready reconstruction of CDT or the Central Department Store on the large thoroughfare that is Aleje Jerozolimskie. The building was completed in 1951 following a design by Zbigniew Ihnatowicz and Jerzy Romański and quickly gained a reputation as one of Warsaw’s most impressive examples of modernism. In her Culture.pl article, Anna Cymer writes the following about CDT:

The glass surface of the elevation, rounded corners, the undercut ground floor, the inclined parts of the roof, and later also the impressive neon on the façade: all these became identification marks of the CDT Department Store.

Corresponding nicely to its metropolitan surroundings, the downtown structure became one of the city’s favoured commercial spots. In the 1970s, it became a children’s toy store and that’s how it’s often remembered, giving the place an additional sentimental quality.

In 2014, reconstruction commenced according to a design by the bureaus AMC – Andrzej M. Chołdzyński and Rhode Kellermann Wawrowsky. As time has shown, it left only a handful of the original elements, namely those that make up the framework of the façade. The rest of the exterior is new, albeit faithfully and tastefully mimicking the original. As a result, from the outside the building looks like a better version of its somewhat run-down, old self. Still, some see this as unacceptable and call the new CDT an ‘empty egg shell’. Especially since the interiors were completely refashioned and will now provide not only commercial but also (plenty of) office space. Others argue that after the elegantly executed reconstruction (even the impressive neon that had embellished the façade until the 1970s has been recreated) the soon-to-be-opened CDT is bound to become a Warsaw showpiece.

Emilia

The former Emilia pavillion, 2012, photo: Krzysztof Miller/AG. A visualisation of the pavilion created for the Museum of Modern Art, photo: press materials

The former Emilia pavillion, 2012, photo: Krzysztof Miller/AG. A visualisation of the pavilion created for the Museum of Modern Art, photo: press materialsThe Emilia pavilion, built as a furniture salon in 1969 according to a design by Marian Kuźniar and Czesław Wegner, is another prominent example of Warsaw’s modernism that’s undergoing reconstruction. This case is unlike any of the earlier-described ones, however, as it involves the relocation (yes, relocation) of the entire building. If not for this drastic move, the pavilion would’ve perished – in 2015, a decision was made to build a skyscraper in its place in Emilii Plater Street.

Its glass exterior and reinforced concrete framework were carefully deconstructed (a rather fitting term given that the building housed the Museum of Modern Art for the last ten years, a haven for deconstructivism) in 2017 and are currently waiting to be rebuilt in the nearby Świętokrzyski Park. Many of the original elements that have been salvaged (such as parts of the eye-catching, trapezoid-wave roof) will be used in the process.

The website Bryla quotes Wojciech Kotecki, the architect in charge of the reconstruction, as saying:

The Emilia building was designed in the 1960s as a free-standing exhibition pavilion raised in a green area. In the 1990s, high-rises surrounded it very tightly. At that time, it lost its initial qualities and original surroundings. By locating Emilia at the edge of the Świętokrzyski Park, we give it a chance to function in the kind of space it was originally thought up for.

The new Emilia is meant to include a coffee house, exhibition areas and workshop spaces, as well as recreational spots for things like playing board games or holding dances. The presence of many plants on its premises is to become one of its trademarks, turning the place into a kind of culturally-animated orangery. If all goes well, its construction might even begin before the year passes. Seems like something worth waiting for.

What other Warsaw buildings will end up gaining a second life? Only time will tell, though there are petitions for certain famous old buildings to return, with many locals eager to see the past come alive again. In a city that suffered so much loss and was scarred by WWII, re-creating and revamping historical buildings is often an issue that engages emotions. But it generally seems that the here-described approach of ‘preservation meets modernisation’ is one that offers a sensible way to both respect tradition and go along with the times.

Author: Marek Kępa, March 2018