Did you have any worries before the journey?

I was afraid that the film wouldn't be universal. I imagined that our case was somehow different, and that we were unique. Thankfully that was not the case - we are ordinary people, with normal problems, enveloped in relations which involve many other people. After meetings with the public, I can see that in Father and Son, people find a truth about their own family.

Were you not afraid of accusations of cinematic patricide?

I knew that some would really like the film, others not at all. Everything depends on the private story of the viewer. The public is divided into two camps: women and young people support me as a son and a director, the slightly older viewers on the other hand, and men, take my father's side. This divide is understandable and clear, especially that in the film I clearly side more with my mother.

Your father and you have painful conversations, but you show a lot of affection towards each other…

…that's the nature of this feeling colloquially called love. Love is empathy and anger, the desire to be with each other and the will to be cut off from one another. It's a strange conglomeration of contradictory feelings.

You once said, that if there is something you don't understand, you like to make a film about it. What did you manage to understand from Father and Son?

That among others, being an adult meant that we could relinquish the search for our parent's acceptance, that we stop caring about what they think. Only then are the choices we make truly ours, as opposed to dictated by the approval or objection of the other. Maybe I'm only becoming an adult now? (laughter)

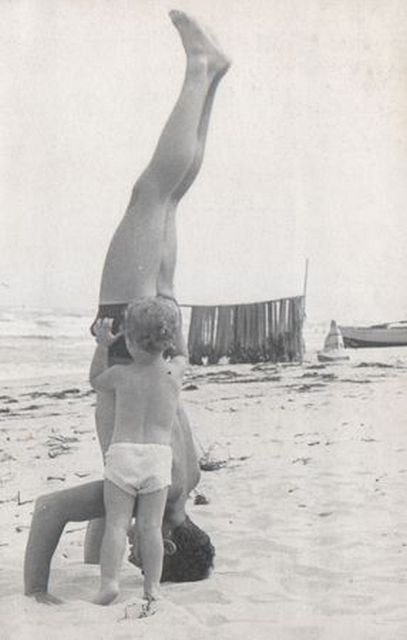

A still from Father and Son by Paweł Łoziński, photo: KFF.

A still from Father and Son by Paweł Łoziński, photo: KFF.Why did you make two separate films?

You should ask my father that. I don't know what made it impossible for him to sign his name under Father and Son. Maybe he felt a strong need to compete, and this was his way to say: "I'm also going to make a film, and it will be just mine". In any case - there are two films. My father took Father and Son, and based on it, he made his own documentary. Something shortened here, something added there, something censored. I have the impression, that in his version, my father put a sock in my mouth, and decided to make himself look a bit more beautiful.

The differences between the films are rather small…

Unfortunately. Father and Son on a Journey is very similar to my film when it comes to its construction. I think that 85 percent of the scenes are edited in the same way. That's a pity, had we known from the beginning that my father would have wanted to make his own version, we would have filmed differently. We would also have taken two different editors, and it would be possible that in the end we would have two very different documentaries. What we ended up with is a cinematic experiment of the "find the seven differences" sort. That's the job of a film critic, not a viewer.

You speak very little about the cinema. Why?

I wasn't making a film about a director, but about a father. I was really scared that if we start talking about our career and artistic rivalry, nothing will be universal anymore. I wanted my film to be about a random father and a random son. About a family, its disintegration, the onset of complicated roles.

When you look at the family as an entity, are you more of a Bergman or a Woody Allen?

Maybe there's no need to choose? One and the other, it depends on the mood. A family is an unsorted sea of topics. Very different topics. I think it's Tolstoy who wrote that all happy families are alike but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. There's a conflict in every family, something that remained unspoken, a silence, a taboo or dirt under the carpet. The interesting thing is to look in those places where we hide our unresolved issues.

Not easy to avoid exhibitionism…

I was very skeptical about putting a camera in my own home. I remembered all the discussions that came up when Marcin Koszałka's Such a Beautiful Son I Gave Birth To / Takiego pięknego syna urodziłam came out. I didn't think something terrible had happened, I was intrigued by what Marcin had done. But I believe that not everything can be told in a documentary, because some things are too painful and personal. That's when you need a film with a plot.

Still from Marcel Łoziński's Father and Son on a Journey, photo: KFF

Still from Marcel Łoziński's Father and Son on a Journey, photo: KFFIn one of the scenes your father speaks about himself as a Jewish father. Do you sometimes feel like a Jewish director?

When I was seven or eight, I found out that my parents and grandparents were Jews. That occurred in a way that is rather usual for these types of situations. I came home very happy and told my parents that on the playground there was a Jew and I had just beaten him up. They didn't have a choice, they had to say : "We have to tell you about a certain difficult truth, but there's nothing to worry about because a lot of famous people...(laughter)." That's a masterclass in selling bad news.

My parents survived the war in terrible conditions: father was in an orphanage, mother was deported to the East to Uzbekistan, where famine reigned and people lived in primitive conditions. They had a difficult start in life. We are built from history. In order to understand who I am, where my "issues" with life came from, I wanted to try to go back to what my parents went through.

It's hard not to look at your roots. It's a natural reflex. My brother, Mikołaj wrote his The Book / Książka because, as far as I think - he also had the need to understand who our parents, grandparents were and who he himself is. That's the reason I reached for the camera.

Your next film is supposed to be a story about your family.

I am making a film about divorce mediation, about the need to talk in the face of conflict. There are great emotions involved, which I always looked for in a documentary. I think, that a film like this, is also an occasion to create a collective portrait of us Poles today. The dramas that take place at the mediator's reflect our entire contemporary world. A divorce is a complicated affair: you have to part with the mortgage, divide the dog, set down exactly when the husband can see his child and where he can take him.

These conflicts involve religion. Among my protagonists there is a certain pair: the woman is highly religious, the husband is a struggling anti-Catholic. I have no idea what brought them together? They had a Church wedding. And even though she didn’t want to divorce, after a couple of meetings she understood that there was no putting back her relationship together. Like a lens, mediation concentrates the truth about people. Not only about these precise protagonists, but about all of us.

Author: Bartosz Staszczyszyn, November 2013. Translated by Mai Jones