Sławomir Mrożek's plays present straightforward situations, his characters' everyday actions revealing human behaviour in all its comic absurdity. The best-known plays written by Mrożek before his emigration to France in 1963 and later to Mexico are The Police, The Turkey, Karol and The Game. His most famous play, Tango, staged for the first time in 1965, is a biological, psychological observation of the creation of totalitarian mechanisms, and brought him international fame.

The Emigrants, Mrożek's second most-frequently staged play, was written while he was living abroad. It is a study of two different forms of exclusion, juxtaposing idealism with the solid common sense of a political immigrant who left his country for the sake of money. In the 1980s, with plays like The Ambassador and The Portrait, Mrożek continued his research into characters as if theatre were his laboratory, concentrating increasingly on matters of psychology while using them to demonstrate historical and political mechanisms.

In the 1990s Mrożek wrote three key plays: Love in Crimea about the fall of the Russian empire, The Beautiful Sight, presenting the Balkan War from the perspective of two carefree Europeans on a seaside holiday in one of the countries of the former Yugoslavia, and The Reverends, a humorous analysis of religious hypocrisy. These three plays provide a window on the last decade of the 20th century, a time of war, disintegration of values and systems based on genocide. Though these are very important subjects, Mrożek does not treat them directly. Instead, he twists them: War becomes an annoyance for tourists, the chaos of the last days of totalitarianism is irresistibly funny, the priests are sitcom characters seen through a distorted mirror. Mrożek's answer to contemporary reality is knowing laughter.

Sławomir Mrożek - Portrait of a Writer

Mrożek, among Poland's most internationally famous writers, was an uncommonly versatile artist, moving freely from one form of expression to another. As the literary critic Tadeusz Nyczek writes:

The thing that is often emphasized is the sheer scale of his creativity, which is unprecedented, almost inconceivable and hard to encompass. There are his drawings, to which he has remained faithful for perhaps the longest time; and his grotesque-philosophical prose, one of the most unique pinnacles of post-war literature, which includes not only stories but also two short and funny novels. Then there are his plays, his best-known achievements, as well as screenplays, two of which he directed himself. But there is also his journalism, made up of essays and feature articles of the highest quality. [...] His letters to Jan Błoński and his correspondence with Wojciech Skalmowski [...] are 'postal literature' of inestimable intellectual and artistic value. [...] His brilliance lies in a particular internal act of courage, the masterful gesture of a liberated artist, which says: look, even this I can do, I can sign with my own name both the most serious and the most trivial of things.

– Tango z Mrożkiem / Tango with Mrożek in the anthology on Mrożek Tango z samym sobą / Tango with Himself, 2009

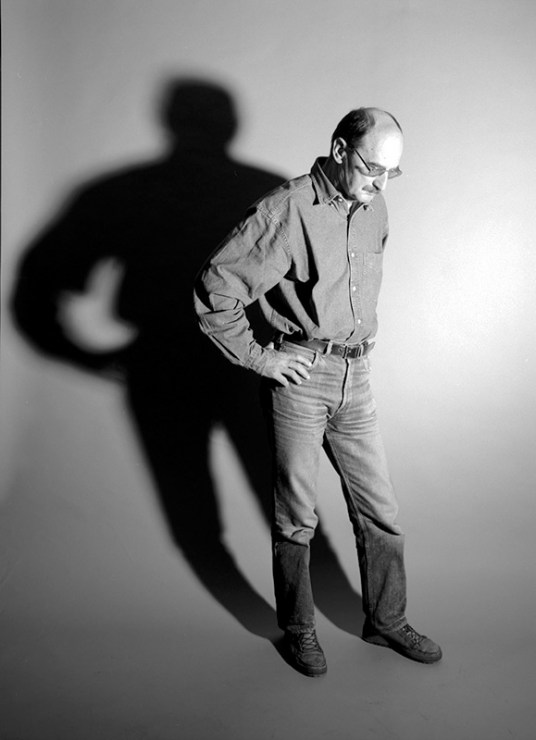

Sławomir Mrożek, Stockholm, October, 1992, Photo by Woody Ochnio / Forum

Sławomir Mrożek, Stockholm, October, 1992, Photo by Woody Ochnio / ForumHe was born in 1930 in Borzęcin, but his family moved to Kraków soon afterward, where Mrożek's father, Stanisław, held a position at the post office. After the war, which Mrożek spent in the countryside, the future playwright attended grammar school in Kraków and then enrolled at the university. He was not very happy with any of the three subjects he studied (architecture, Oriental studies, art history), and began his artistic career as a draughtsman and journalist. He began working as a draughtsman in 1950 and soon became popular for the satirical sketches he made for the magazines Przekrój and Szpilki. From 1950 to 1954 he worked at the editorial office of Dziennik Polski, writing articles in support of the "building of Socialism" that zealously conformed to the demands of ideologically correct journalism. This youthful fascination with communism passed quite quickly, his ideas changed radically, and Mrożek never denied his past. He wrote:

Being twenty years old, I was ready to accept any ideological proposition without checking it too carefully – the only thing that mattered was that it was revolutionary. [...] It was from among people like me that they once recruited for the Hitler Youth or the Komsomol [...]. Frustrated, errant and rebellious youths are present in every generation, but what they do with their rebelliousness depends only on circumstance.

– Baltazar. Autobiografia / Balthazar. An Autobiography, 2006

The young writer's journey from belief in the communist system to scepticism and eventual rejection of it gave him experience of the way social mechanisms operate. As the critic and literary historian Jan Błoński writes:

Stalinism often broke or at least derailed artists. Mrożek, paradoxically, was strengthened by it, because it revealed to him de visu the power of the stereotype, the imposed code and the interpersonal mould, which, by escalating and swelling, destroys itself in the end. […] In doing so, however, it often litters the society with bodies.

– Wszystkie sztuki Sławomira Mrożka / All the Plays by Sławomir Mrożek, 1995

According to Tadeusz Nyczek,

The four-fold salto mortale (the pre-war petit bourgeois) – rural stabilisation, the devastating war, the revolutionary inspiration of communism and finally the escape from the hell of naivety – all of this had a decisive influence on the nature of Mrożek's creativity. Feeling shattered himself, he decided to become a broken mirror for the fractured reality of socialism in Poland. This broken mirror began to reflect Polish life in its dozens of fragmented forms, in its ridiculous language, its topsy-turvy behaviour and the whole absurdity of living in a dustbin that propaganda defines as the joy of building a socialist homeland.

– Tango with Mrożek

The Progressive, and Mrożek's Absurd Tales

Mrożek mocks the stereotypes and absurdities of daily life in the Polish People's Republic in Postępowiec / The Progressive, the famous column that he wrote and illustrated for various periodicals from 1956 to 1960. The wit of The Progressive, as Błoński wrote in All the Plays by Sławomir Mrożek, is based on the unmasking of journalistic conceits like the informative telegram:

'From the scientific activities of the UNO: The spokesperson for research into the effects of work in agriculture and forestry has declared that - as heretofore - the use of professors to cut down forests does not have any influence on the quality of timber.'

Mrożek's satire also took the form of spoofs of introductions to social programmes:

'Towards a prophetic vision. Throughout the country there will be a collection of empty vodka bottles. These bottles will be used for the construction of glass houses, as has already been foreseen by Żeromski.'

The humour, surreal imagination and sense of the absurd that, in The Progressive, were used primarily to amuse the reader, began to take on a deeper and darker significance in Mrożek's writing. In his mature prose and plays, these qualities are used as tools for constructing a perceptive, often cruel analysis of social and existential issues. Kind-hearted mockery would, over time, be replaced by bitter, ambiguous irony.

1953 was the year of Mrożek's debut as a prose-fiction writer, with two collections of his satirical stories appearing: Opowiadania z Trzmielowej Góry / Tales from Bumblebee Mountain, published by Czytelnik in Warsaw, and Półpancerze praktyczne / Practical Half-Armour, published by Wydawnictwo Literackie in Kraków. As a creative writer, he was still trying to find his own voice. As Błoński reflects,

If it were not for the age of the author, I would say that the stories in Mrożek's early books take a fatherly tone in criticizing society's defects and vices, complete with a sensible excuse and a smile; they are rarely humiliating and are not generally frightening. To today's reader they seem quite simply... infantile! [...] Mrożek still hadn't torn his way through to reality... through the grotesqueness and the absurdity. [...] Only then, with the appearance of nonsense and death, could Mrożek's talent really shine [...].

Sławomir Mrożek, Cracow, 1960, photo by Wojciech Plewiński / Forum

Sławomir Mrożek, Cracow, 1960, photo by Wojciech Plewiński / ForumPółpancerze praktyczne is an amusing story about shop assistants in a department store wondering how to sell a rather peculiar item: "four hundred new pieces of half-armour, 16th-century model". The armour had been delivered to them by mistake, but that did not change the fact that "goods are goods and must be sold". After unsuccessful attempts to dispose of the half-armour, an old man turns up at the shop and pretends to be greatly interested in the goods. It is not hard to guess what happens next: Negotiations between the old man and the salesperson attract other buyers, and before long everyone in town wants to own "elegant half-armour". Soon the stock is selling like hot cakes.

In this simple story poking fun at the herd instinct, Mrożek juxtaposes old props (half-armour, 16th-century model) with the harsh reality of the People's Republic of Poland. This technique – which involves, as Błoński notes, seeing the "old" in the "new" and vice versa – was then used by Mrożek in the more sophisticated stories of the collections Słoń / The Elephant (1957) and Wesele w Atomicach / The Ugrupu Bird (1959). The critic notes,

When applied with rigid consistency, this literary device – which is, in essence, quite simple – creates a world that is completely schizophrenic, in which the word and the thing (the intellect and the act of living) have parted irrevocably.

Błoński cites a fragment of the story Wesele w Atomicach:

'That was the moment that they started to transform nature. That which was forested became both civilised and improved, while the desert was forested. The course of the river was altered so that it flowed in the opposite direction. The road to the church was moved a little further away, but in my yard there appeared a huge dam of significant economic importance, so that the doors did not close entirely and it was only with difficulty that you could leave the house'.

Opposing the old and the new while tragic-comically intertwining them is a characteristic of Mrożek's works. It appears most vividly in his play Tango (1964), in which the world-view of the avant-garde (represented, paradoxically, by the older generation) clashes with the conservatism of the young Artur.

The co-existence and conflict of different historical realities was always present in the linguistic tissue of Mrożek's writing. In the story Sjesta / Siesta from the book The Elephant, two men are conversing. One is a priest, the other introduces himself as a "maître de danse", and both, although figures from the 19th century, are participating in the construction of a new socialist homeland. This disparity is reflected in the story's language in which old-world conversation full of courtesies and rhetorical ornaments is peppered with primitive party jargon. Expressions such as "please allow me", "if Father would be so kind" and "please forgive my importunity" are mixed with ideological gibberish like "hostile propaganda will once again take its prey and will go to the masses whereas we above all have to be oriented towards the masses".

Błoński writes:

In reading Mrożek, the modernists laugh at tradition while the reactionaries laugh at the progressives. In the same way, Gombrowicz once shuffled the cards for Pimko and the Młodziak family [in the novel Ferdydruke]... However, Mrożek was undoubtedly more fascinated by the past – or perhaps he saw it more clearly? He noticed that you cannot mock it with impunity. This oscillation between mockery and nostalgia creates, along with the humour, a certain disquiet. [...] Backward traditionalism and the flaws of revolution, Polish lateness and bourgeois absurdity – the writer throws it all into one bag, as if to say that even if we can recognize how outdated our values are, we are incapable of creating new ones.

– All the Plays by Sławomir Mrożek

Sławomir Mrożek in Noir sur Blanc Publishing House in Warsaw, 1st of October 2009, photo by Rafał Guz / Fotorzepa / Forum

Sławomir Mrożek in Noir sur Blanc Publishing House in Warsaw, 1st of October 2009, photo by Rafał Guz / Fotorzepa / ForumMrożek, while mocking the hypocrisy and ossification of small-town customs, also viewed the countryside with tenderness and nostalgia. Perhaps this was because it was, after all, the world of his childhood, a world that had shaped him and that provided an endless source of creative inspiration. His early stories are set in the countryside, and later works such as Moniza Clavier (1967) and The Émigrés (1974) deal with the collision between a provincial protagonist and the so-called Great World.

Critics often emphasise that the language of Mrożek's prose and plays – stylized, rich in allusions and full of references to both "high" and "low" culture – owes a great deal to the writer's familiarity with local idioms, with rural people and the petit bourgeois and with a homey, colloquial version of the Polish language. The article Prowincja / The Provinces, from the series Małe listy / Small Letters, is worth mentioning here. In it, Mrożek analyses the artistic and metaphorical dimension of "provincialism", referring both to Fellini's film Amarcord and to his own roots:

'The longing for the Great World, so characteristic of the countryside, is a sort of a longing for transcendence. The joy of anyone who has managed to tear himself out of the provinces and plunge into the Great World is a mystical ecstasy, the ecstasy of one who has crossed (or thinks he has crossed) the enchanted and cursed boundaries of his own existence. An artist works exclusively through such models because he cannot do otherwise, so any artist who comes from the countryside has it easy. There, the limits on places, people and details, and their relative stability – because changes and exchanges are so slow as to give the impression of stability – enable observation, concentration and contemplation. [...]However, neither can an artist exist until he frees himself from the countryside'.

The countryside, depicted with nostalgia and with the ironic distance of one who has escaped from it, the aesthetics of parody and of the grotesque, and a blend of old and new that seems fantastic yet nonetheless offers a realistic picture of reality – these are facets of Mrożek's world that have been present in his work from the beginning. But there is more. Even in Mrożek's early prose there was a conflict between the delusions of the intellect and the ruthlessness of the body, between culture and nature. In Podanie / The Application, published in the collection Wesele w Atomicach, the narrator – an old man living in poverty and cared for by his son-in-law – writes a petition requesting authority over the world. The absurdity of this demand, made even more absurd by a host of ridiculous arguments, reveals the protagonist's complete mental and physical helplessness.

This is one of the most important themes in Mrożek's work: the dissonance between reality and human ambition and the constructions of the mind. The old man's ranting and his demand for authority over the world serve as a metaphor for a completely reasonable desire to embrace, control and overcome a hopeless situation – or to escape from it, even if it means escaping into the most bizarre fantasies.

Mrożek published his first novel, Maleńkie lato / A Tiny Summer in 1956, and in 1961 he published Ucieczka na południe / Escaping Southwards, his second and last. Both are satires of the Polish countryside. In A Tiny Summer there are certain didactic tendencies, but the writer manages to shed them in Escaping Southwards.

In 1958, the comedy The Police marked Mrożek's debut as a playwright. The play paints a universal portrait of a totalitarian state not one anchored in a specific time or place. In order to survive, the state depends on the existence of some sort of opposition. The play's absurdity comes from manipulating the notion of freedom, the appearance of which serves only to strengthen the police regime. It is hard not to recognize allusions to 1950s Poland in The Police, but the social mechanisms and the conduct of the characters caught up in them are just as comprehensible outside the Polish context.

In three one-act comedies from the early 1960s – Na pełnym morzu / At Sea, Karol and Strip-tease – Mrożek analyses the behaviour and choices of people in dangerous situations. The protagonists of At Sea are Mały, Średni and Gruby – Small, Medium and Fat – who are stuck on a raft without food, arguing about which of them should be eaten by the remaining two. This grotesque idle chatter, with which they try to outdo each other in debating who would be the "just" victim, only serves to delay the verdict, and it is obvious that the law of the strong is on Gruby's side and not on Mały's. In Karol, an optician is visited by a grandfather and his grandson, apathetic attackers who are looking for someone to shoot. In Strip-tease, two men in a mysterious prison try to free themselves either by pretending to be free (in the case of Man 1), or by struggling for real freedom (Man 2). Then a supernaturally large hand removes their clothes, baring them both literally and morally, before handcuffing the men and putting hoods over their heads.

Jan Błoński wrote that the one-act play (referring to Peter Szondi's Theory of Modern Drama) is especially suited to the scenario of entrapment, a common situation in Mrożęk's world. According to Błoński, another thing that works well in a one-act play is the pairing of a smart alec and a lout, a fundamental opposition within Mrożek's work:

All the characters have to do is to bear until death a situation that they not only did not create (which would have given it a tragic twist), but also about whose origins they know nothing. Had the optician ever hear of the hunt for Karol? Did the men know about the hand that roams the streets? What can they do now? They can either falsify reality, as the smart alecs do, or push on and do their own thing, like the louts do. But the deviousness of the smart alecs and the stupidity of the louts (who will lose in any case) evoke laughter. This is a dramatic form that favours both of Mrożek's arch-figures (because surely they are not archetypes). Being trapped means that they can – just like a dirty swarm of moths – spread out all of their misshapen peculiarities.

Mrożek's most noteworthy one-act play is The Emigrants, based on the confrontation between a smart alec named AA and a lout named XX.

The Turkey, Tango and Other Successes

Sławomir Mrożek, Tango, published by Noir Sur Blanc, cover

Sławomir Mrożek, Tango, published by Noir Sur Blanc, coverIn 1960 The Turkey appeared, "a melo-farce in two acts" in which Mrożek crushes the myth of romanticism. A collection of romantic characters are gathered at an inn "on the territory of the duchy". All are paralysed by total indolence, able to transform neither lofty ideals nor simple willpower into any real activity that could break through the ubiquitous hopelessness. But what is worse is that despite this hopelessness, it is still possible to survive:

'Poet: Oh, we have guaranteed upkeep at this inn. It may be modest, but it's guaranteed – it's enough to live on. There are not many hopes for the future, only a few. But it is warm, even though it smells a bit – but not too much. In any case we cannot escape from here even if we wanted to, because there is nowhere to go, the roads are bad and the wilderness all around is frightful. Of course, you could set about doing this or that, but what for? It won't change anything, it won't make anything better, it won't make anything worse or alter anything at all. In any case, there is still no answer to the principal question'.

Helplessness and universal apathy also pervade Zabawa / The Party (1962), in which three farmhands, hearing the sound of music, go looking for "the party". But when they finally get into the "club room" where the party is supposed to take place, all they find is silence and emptiness. Tadeusz Nyczek sees in this play a metaphor for post-war Poland, where hope was followed by bitter disenchantment with a new system promising a "better tomorrow". Jan Błoński, on the other hand, draws attention to the fact that the protagonists in The Party are different from the simpletons of earlier plays, because they want not only entertainment but also access to culture. However – and this is the catch – they are unaware aware of this need themselves:

Because the puzzle of shallowness and limitation stems not only from the conditions in which a person lives but also from within himself. [...] Who is preventing our threesome from enjoying themselves in moderation? [...] But the farmhands cannot articulate their needs, let alone identify any values at all capable of satisfying those needs. That is why they are ridiculous. But they do feel those needs, they want those values! This is a world of eternal frustration to which the lout has been condemned, but the moment he feels this frustration he begins to take on features that are more profoundly human! The conflict between this need and the possibility of satisfying it also takes on, if not an air of tragedy, then at least one of seriousness.

– All the Plays by Sławomir Mrożek

The farmhands in The Party longing for "higher values" do not suspect any distortion of culture. They are unaware of the pseudo-scientific hypocrisy of which The Emigrants' dim-witted XX accuses the intelligent AA.

1964 brought a breakthrough in Mrożek's career with the publication of Tango, the first of his plays to achieve worldwide recognition. The play immediately won the acclaim of theatre critics and audiences, and continues to be celebrated today. In terms of the accuracy of its social diagnoses, it ranks alongside Wyspiański's renowned and innovative play Wesele / The Wedding (1901). In the opinion of Tadeusz Nyczek, Tango is one of the three most important post-war plays in Poland, along with Tadeusz Różewicz's Kartoteka / The Card Index and Witold Gombrowicz's Ślub / The Marrigae, which had been Mrożek's inspiration.

The wedding ceremony Artur plans in Tango is supposed, as in Gombrowicz's play, to restore order in a world of shattered norms. "Nothing is important in itself, in fact it is nothing at all", says Artur to his fiancée, persuading her to marry him. "Everything is neutral. If we do not try to give things some character, we will drown in this dullness. We have to create meaning if it does not exist in nature".

The only structure to have survived in the world of Tango – which disintegrates before our very eyes – is the family, which is also a symbol for society. However, it is a family in which all the roles are reversed. The father, Stomil, is a parody of an avant-garde artist, as carefree as a child. Artur, his 25-year-old son, on the other hand, demands responsibility, respect for tradition and the observance of clearly defined rules. Faced with an absence of any hallowed values against which to rebel, Artur's only available form of protest is to demand those values. Thus his youthful rebellion takes on the paradoxical form of conservatism. Mrożek has used a family drama and the universal motif of the generation gap to reveal the rules governing social processes. In portraying this conflict between a father and son, as Tadeusz Nyczek writes,

Mrożek brilliantly captured the specific nature of a 20th-century family, in which conservative and progressive, positivist and anarchist behaviours are alternately repeated. But this is not the main strength of 'Tango' because this structure does not only apply to the 20th century. Mrożek's greatest observation was that the co-existence of these behaviours leads immediately to mutual assault, making oppositional coexistence impossible. The leftist anarchist Stomil 'assaults' both the conservative Uncle Eugeniusz and his sister, Grandma Eugenia, as well as his son, Artur, who is still unshaped by ideology. The response to this two-directional Gombrowiczian assault is a counterattack in which, united in common opposition, Artur and Eugeniusz 'assault' Stomil, before they are all assaulted in the end by the ideologically neutral Edek.

Edek is the essential Mrożek lout. Amoral, he always "knows what's what" and is driven by animal instincts, ready to use violence to achieve his own comfort and entertain himself. He is the incarnation of naked biology and ruthless nature, which will always triumph over culture. Edek's victory is the victory of nihilism. One can also read Tango, as Błoński claims, as a philosophical treatise on the history of freedom. According to this interpretation, the cause of Artur's defeat is his love for Ala – and his inability to understand that absolute freedom demands absolute solitude.

Krawiec / The Tailor was completed the same year, but it was so similar to Gombrowicz's Operetka / Operetta, which that writer had yet to complete, that Mrożek decided not to print his play; he would not publish it until 1977. This incident prompted him to write the article Uzupełnienia w sprawie Gombrowicza / Supplements to the Gombrowicz Affair, in which he presented his opinion on his most important literary antecedents, including Witkacy, Wyspiański and Fredro:

I started reading his [Gombrowicz's] books when I was in my twenties, and they made a significant impression on me. [...] During the next few years he was present in my mental life, first as a master and later as an opponent (in the sense that I was still under his spell, but I was questioning to myself the versatility of his theses and style). While I was writing 'The Tailor', I was still under his influence (though not only his, since I have always been simultaneously affected by many people and many things). The opposition of culture and of nature was obviously not of his invention; this is an idea I came up with myself, as everybody must always do. What did come from him, on the other hand, was the literary method of expressing and treating this opposition. [...] But in this case I ought to say that if Gombrowicz had not written 'The Marriage', I would not have written 'Tango', or at least not in the form in which I wrote it.

– Small Letters, 1982

Moniza Clavier, Vatzlav and The Emigrants

Mrożek left Poland in 1963. By that time he was already a well-known author in Poland and internationally, with work translated into German and French. (He remained abroad until 1996, living in Italy, the U.S., Paris and Germany, then in late 1989 he settled in Mexico.) In August 1968, he used his columns in the journal Kultura in Paris to protest against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces, and he applied for political asylum in France.

He often wrote about emigration and its associated quandaries in his correspondence with his friends, questioning what it actually meant to be "at home" or to be "foreign". As he proclaimed in one of his letters to Błoński:

How can I help it if my very organism is irritated by my 'our-ness'? Screw it. I feel better when I am not 'one of us', because then my external state moves closer to the truth, to my internal state. [...] Screw it when, in order to get in somewhere, someone comes up to me and says something like: 'Oh, here is our Mrożek'. That is why I left Kraków – so as not to be 'ours', public property, like the tower of St Mary's Church is 'ours'. Our-ness, class-ness, mate-ness – everything somehow gets stupidly mixed up in all of this, above all individual responsibility. [...] That is why, when I'm not 'ours' but rather foreign, I feel that the situation is psychologically clearer and I can rest. (Chiavari, October 19, 1963)

In The Emigrants (1974), Mrożek uses his experiences as a man from a poor Eastern European communist country trying to find his place in the Western world of prosperity. He also analysed East-West relations in the plays Vatzlav (1968), Ambasador / The Ambassador (1982), Letni dzień / A Summer's Day (1983) and Kontrakt / The Contract (1986), as well as in the story Moniza Clavier (1967).

In Moniza Clavier the narrator is a young Pole, a tourist from the countryside, who wanders around Venice with a cardboard suitcase full of kabanos sausages. By chance he catches the eye of a famous actress, and she invites him to a reception full of artists, snobs and rich dandies. Nobody knows the young Pole's real identity, not even the beautiful Moniza, who is enchanted by him. Lonely and filled with psychological complexes, he is unable to find himself in this exclusive demi-monde and tries to impress the company by reverting to the romantic stereotype of a hero from behind the Iron Curtain who lost his teeth fighting for freedom. When this masquerade causes Moniza's society friends to mistake him for a Russian, he eagerly exploits the misunderstanding and pretends to be a picturesque foreigner from the wild steppes. Finally the poor provincial man is unmasked by an unexpected encounter with a fellow countryman.

In this story, the author paints a masterful picture of the power that stereotypes had in shaping 1960s (and probably also contemporary) Polish attitudes toward what they imagined was a "better" Europe, as well as the ideas this Europe had about its eastern neighbours. But it is also a story about the emigrant's sensation of being lost. Like so many of Mrożek's protagonists, he dons a mask, gripped by fear and a feeling of inferiority, fighting for social acceptance and advancement. He plays out a hastily-devised role and seeks a safe haven in stereotypes.

Sławomir Mrożek, 1987, Photo by Wojciech Plewiński / Forum

Sławomir Mrożek, 1987, Photo by Wojciech Plewiński / ForumIn Vatzlav, a political dystopia, the expectations and hopes of a Slavic castaway collide with the unhappy reality of the island on which he finds himself, and the whole story is told through the convention of an Enlightenment-era philosophical tale.

Last is The Emigrants, a biting portrait of Poles in a foreign land and a universal study of the condition of exile. In an obscure basement, two flat-mates, the political émigré AA and the economic migrant XX, are talking to one another. The first dreams about one day writing a book about his life's work, while the other accumulates money, dreaming of one day returning to his village, cloaked in an aura of success, to build a house. Their dialogue begins to take the form of a duel, in which AA and XX unmask one another step by step. The smart alec pitilessly shatters the naïve illusions of the lout, revealing his stupidity, while the lout discovers the smart alec's secret: the hypocrisy and pseudo-intellectualism used to disguise his solitude.

AA: You have come to me like a bolt from the blue, like inspiration. [...] I, thanks to you, will finally write my masterpiece. Now you know why I need you.

XX: That's not why at all.

AA: Do you think I would sit here voluntarily in this – as you yourself said – shit, if I were not guided by such a great idea, such a mission?

XX: And I am telling you that that's not the reason.

AA: So why am I sitting here with you? [...]

XX: Because you want to talk.

[...]

AA: That's not true – I have a great idea, I... my work...

XX: Rubbish, your work. Do you think I don't see how you squirm when I get a letter from my family? You go into the corner and start reading a book upside down. I feel sorry for you. Because you don't get any letters.

Critics have emphasised that AA and XX are the most psychologically nuanced characters in Mrożek's work up to that point. The protagonists of his earlier stories and plays, moulded on social, literary and characterological stereotypes, were merely puppets manipulated by the author to achieve a comic effect. The character of Artur in Tango was also shaped differently. As Błoński pointed out, Artur may not yet be an individual "living person", but neither is he a stereotype; since his actions introduce an unpredictable element to the plot, he can be seen as a dynamic model of family and social behaviours. In The Emigrants, though, Mrożek draws multi-dimensional portraits of exiles. As for the confrontation between the smart alec and the lout, it is a metaphor of the duality that exists in every one of us. In Tango with Mrożek, Tadeusz Nyczek writes:

I tried many times to think of The Emigrants as a monodrama.These two roles seem to contrast completely. But in fact the intelligent, educated AA and the loutish XX, hungry for simple well-being, are after all the same person. Communication between them seems impossible, but in fact the existence of the one is impossible without the other. [...] Together, they make up the most penetrating metaphor for the essence of a Pole that I know of in all contemporary Polish literature, particularly since this one is dramatically doubled. I think this is also the fullest self-portrait of Mrożek himself, the man of the world from Borzęcin.

The Slaughterhouse

A year before The Emigrants, Mrożek had published Rzeźnia / The Slaughterhouse (1973), a radio play whose stage adaptation was directed by Jerzy Jarocki at the Teatr Dramatyczny in Warsaw in 1975. In The Slaughterhouse, the playwright writes about the condition and meaning of art, showing through a distorting mirror the conflict between tradition and the avant-garde, and between culture and nature. The protagonist of the radio play, a violinist, is an untalented mummy's boy who offers his youth to the spirit of Paganini in return for musical genius, willing to do anything to win back a flautist. But Paganini turns into a butcher, and the philharmonic becomes a slaughterhouse where a concert for two oxen, a battleaxe, a knife and an axe will take place. Mrożek mocks the Witkacy-like myth of the artist to whom the Mystery of Existence is revealed, as well as art that wants to compete with life in terms of "guts". Błoński writes about the play that,

Mrożek says quite clearly that he cannot believe in the metaphysics of art, but also that rolling around in meat and splashing passers-by with paint arouses within him reluctance and disgust. He asks for moderate art, as it were, but at the same time he admits, at least in The Slaughterhouse, that he can only call for moderation through mockery.

Błoński notes, however, that the action of the play takes place entirely in the imagination of the violinist, emphasising the author's own detachment from the events and arguments presented in the play. It is quite possible that the entire plot is just the creation of the mind of one individual, with whom the author does not personally identify. Therefore, The Slaughterhouse can be considered, like Gombrowicz's The Marriage, to be part of the trend toward what is called Ich-Dramaturgie, or "I" dramaturgy. Over time, the individual and his subjective world began to take on more importance in Mrożek's work.

In the Mill, My Good Sir

This shift can already be seen in the story We młynie, we młynie, mój dobry panie / In the Mill, in the Mill, My Good Sir (1967), a mysterious tale with a grotesque, dream-like plot. The story takes the form of a monologue of a man who "was a farmhand for a miller" and who is taking a critical look at his own past. His memories of people and events come back to him in the form of dead bodies borne by the river. The first drowned body is a moustachioed gentleman with a gold star, once a figure of great authority for the protagonist; one could even recognize Stalin in this dead "overlord".

Soon, the farmhand starts to fish out other corpses, including a friend from the army and a woman he once loved. One by one, he buries his old loves, friends and acquaintances – the whole of his past life. However, when his own corpse appears he cannot bury it like the others, since that would mean burying himself alive. In reclaiming himself from the past (even if only in the form of his own corpse), the protagonist rediscovers his autonomous "I", but the result is that he feels like a foreigner in the human world. So he takes a lonely journey along the riverside, letting the corpses drift in the current so as to keep an eye on them. The old-fashioned, anecdotal language used in this story serves a different function than in previous works. It is no longer used to poke fun at provinciality and backwardness, Błoński writes:

Before 'We młynie...', stylisation was usually a tool of parody in Mrożek's work. In 'We młynie...', however, old-fashioned language allows us to talk about the beginning and the essence of our own experience, which is based on that which is the most simple, the most elementary. It allows us to penetrate the core of the protagonist, harking back to primeval symbols: the water of time and the mill of events, a forest homestead (a symbol of safety), the journey of life that must be taken on foot, the town inn, the farmers' market and the church fair. The anachronism of the world presented to us and the stylisation of genre and language are no longer intended as parody to sweep away the relics of the past. They do not bring to mind a false or mystical 'I', but rather, on the contrary, the most authentic 'I' possible.

Increasing introspection is one dimension of Mrożek's creative evolution. But starting in the 1980s, the writer also began to take a more direct approach to political and ethical themes, abandoning masks, allusions and surrealistic metaphors. As an émigré, he always kept a careful eye on Polish affairs, as is visible in his play about Lech Wałęsa, for example. In Alfa / Alpha (published in 1984 in Paris), Wałęsa has noble intentions but is ultimately unsuccessful, as the author himself stated in a letter to Wojciech Skalmowski. After the introduction of martial law in Poland, productions of Alpha were banned, along with two of Mrożek's other plays, Vatzlav and The Ambassador (1982).

The Ambassador and Denunciations

The Ambassador is a play about the indomitable spirit, written in the vein of Zbigniew Herbert. The action takes place in a totalitarian state, in the embassy of a democratic country. The Ambassador is visited by the Plenipotentiary of the local government, who presents him with the gift of an enormous globe on which the continents have been left off, because "politically, they are not yet exactly as they should be". Some time later, the blue globe bursts open and out comes a man, an escapee from the globe factory, who asks for asylum from the embassy. When the Plenipotentiary demands that the escapee be handed over, the Ambassador refuses. But soon, he finds out that his democratic government, with which he has been unable to make contact for some time, has ceased to exist. However, the local authorities are willing to keep the embassy of the non-existent country because they need an enemy, even a fictitious one, against which they can unite a society saturated with propaganda. But the Ambassador has no intention of participating in this manipulative charade. In Błoński's view,

His decision to refuse to cooperate – a heroic decision – is from the beginning a disinterested act and, what is more, one devoid of practical consequences. It does not change anything and does not help anyone, except morally. [...] After a lengthy discussion with the Plenipotentiary, [the Ambassador] states that, in the face of total nihilism, only resistance to the point of sacrificing of one's life can offer evidence that 'all of this' is not just 'one great cosmic bluff'. It is this sacrifice, although motivated only by honour, which proves that man can rise above the order of nature, above a system based on naked power and necessity.

The Ambassador, left in complete solitude and abandoned both by his distant government and by the people closest to him, remains indomitable until the end. Nor does he lose his sense of responsibility for the man to whom he has granted asylum. This was the first time that such a protagonist – noble and invincible – appeared in Mrożek's work. Never before had the writer spoken so openly about the need for courage and solidarity in the face of violence.

However, this does not mean that he lost his contrary spirit in the 1980s. During martial law, Mrożek also wrote Donosy ["Denunciations"] such as this:

TO THE MINISTRY OF CULTURE

I report that we as volunteers has completed the action of fighting illiteracy in our district. The last illiterate was hiding in the bushes on Górka Piastowska but we has found him. He defended himself a bit but me brother-in-law whacked him with a stanchion and I whacked him one as well. So there are no more illiterates.

While fighting, we has found some glasses and a book in a foreign language entitled "Les Pensées". That means that he could not read in Polish.

In his right pocket, he had a membership card of the Union of Polish Men of Letters but his Union was disbanded long ago, which means that the membership card is invalid.

That is why we ask you to call off the investigation and offer us a reward as educational activists in the field.

Alphabetically yours,

Me and my brother-in-law

However, Mrożek's plays from this period take a more serious tone, as the author's bitter diagnosis of reality, only lightly hinted at before, finally appears un-camouflaged. The moral message no longer hides behind the screen of humour.

The Portrait

In Portret / The Portrait (1987) – a play filled with references to Adam Mickiewicz's acclaimed Dziady / Forefathers' Eve and Kordian, and to Gombrowicz and Miłosz – Mrożek comes to terms with his youthful fascination with communism. The play is about "Stalin's children", people whose lives have been destroyed either through blind obedience to the regime or in the destructive battle against dictatorship. The author places Bartodziej, a former informer, face to face with Anatol, a political prisoner who, after serving 15 years, has just been released from prison. In contrasting their fates, which appear at first to be completely different, Mrożek reveals the two protagonists' hidden similarity: Both are weak people without any real ideas in their lives. The dreaded tyrant was, for both of them, the only thing providing meaning to their existence, an incarnation of the Spirit of History.

On Foot

In Pieszo / On Foot (1980), a play written seven years earlier, Mrożek returns to his youth, or rather to his adolescence. The play takes place during a critical moment in Poland's history – the last days of the Second World War and the beginning of communism. A father and his 14-year-old son, in whom it is not difficult to recognize the writer's alter ego, are following the advancing front in search of the boy's sick mother. At an abandoned railway station, they meet several other wanderers: the eccentric thinker-artist Superiusz (a figure based on Witkacy) and the lady tormented by him, a lonely teacher, a devious female merchant and her pregnant daughter, the untrustworthy Lieutenant Zieliński and the Bruiser.

They all spend the night on the platform, waiting for a train and drinking moonshine from the merchant's supplies while a blind musician plays the violin. But when they finally hear the noise of approaching wheels, it turns out to be a sinister invisible ghost train that the teacher sums up in one word: transport. The exhausted wanderers fall asleep, with the exception of the terrified son and Superiusz. The latter takes his own life, as his prototype Witkacy had done in 1939, after Poland was invaded by Germany and the USSR.

When the protagonists of the play meet again in the epilogue, after the "liberation" of Poland by the Red Army, they appear in new roles and configurations. The father and son are the only ones not to succumb to the temptations of communism, but rebellious outburst are equally alien to them. All they want is to return home and live a normal, decent life. According to the father's simple motto, "A man should be honest and that's all".

On Foot is an example of epic drama whose epic nature appears, first of all, in the equal distance the author maintains between himself and the characters. But it is also visible in the lack of dramatic tension, since the characters' interactions are, in principle, random; it is not their conflicting opinions but the turmoil of history that decides their fates. The play's tension, as Jan Błoński remarks, is caused not by personal interactions but by the universal fear of death. Lastly, the play's epic nature is evident in its scenes of fantasy, which betray the presence of a concealed omnipotent narrator selecting certain episodes and presenting them to the public.

In the 1980s, On Foot was considered Mrożek's polemic against the falsified vision of Polish reality in the Andrzejewski story Ashes and Diamonds that had been made in a famous film by Andrzej Wajda. To this day, the play remains a perceptive panorama of Polish society around the end of the war and the imposition of the People's Republic of Poland. It is also a play about a world shattered by death, and about the phantoms that haunt the memory and the subconscious. But On Foot can also be interpreted, as it was by Tadeusz Nyczek, as the story of the young writer's maturation:

Although the association is a little risky, this work, one of Mrożek's most unusual, can be traced back to Dante. The father, Virgil, leads the son Dante, the future author, through the hell of war. There they meet souls tormented in various ways: the rural women, the soldier of the underground resistance army, the teacher, the artist and the philosopher. All are travelling through a wartime hell and share a common fate, and it is left to the son to observe this motley collection of characters, which is Poland in a nutshell. The son will one day mature and become one of them, an adult, but he will forever remember his experiences as an adolescent witness. He will be both a participant and an observer, divided within himself.

– Tango with Mrożek

Of the four plays Mrożek wrote in the 1990s, the most important is Miłość na Krymie / Love in Crimea (1993), in which the sentimental story is connected to a synthetic portrayal of the history of Russia spanning Tsarist, Bolshevik and post-Soviet times.

Personal Remarks

The last decade of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st represented a difficult time in Mrożek's life and work. In 1996 he returned from abroad to find Poland a completely different country from the one he had left. Six years earlier, he had undergone a serious operation after suffering an aneurysm of the aorta, then in 2002 he suffered a stroke, which led to aphasia. As part of his therapy to correct the memory loss caused by the illness, Mrożek produced an autobiography, Baltazar (2006). He also came out with Uwagi osobiste / Personal Remarks (2007), a collection of published feature articles with an introduction in which the author, "just in case, said farewell to the public".

Mrożek prepared a great surprise for his readers: At the end of 2010, Wydawnictwo Literackie published his diary, composed of two volumes and over 2,000 pages of notes written between 1962 and 1999. A volume of Mrożek's correspondence with Adam Tarn was also published, entitled Listy. 1963-1975 / Letters. 1963-1975 (2009).

In June 2008, Mrożek moved with his wife to Nice, France, where he died in August 2013.

Author: Krystyna Dąbrowska, September 2009.

English translation: Tadeusz Z. Wolański.