Although he trained as a painter, Robert Rumas soon changed this medium for other media, especially installations. He usually deals with the problem of contemporary identity of Polish society, based on a traditionally strong role of religion and the Catholic Church and other elements of contemporary Polish mythology. Common themes in his works are social manipulation tactics,reli starting with his work in the public space (beyond the boundaries of galleries and museums), creating artistic events and observing the public's reaction to them.

In the years 1987-1991 he studied at the Faculty of Painting, National Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk, where he studied under prof. Witosław Czerwonka, among others. He was an exhibition curator with Galeria Wyspa in Gdańsk (1988-1990), the National Gallery of Art in Sopot (1993-1995), the Baltic-Sea Cultural Centre in Gdańsk (1996-2001) as well as the Łaźnia Contemporary Art Centre in Gdańsk (2000-2003). In recent years, he also cooperated with the Toruń Centre for Contemporary Art. The artist also created the "Antyciała" exhibition at the Contemporary Art Centre in Warsaw in 1995. He lives and works in Gdańsk.

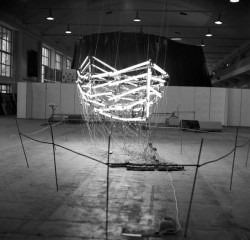

Wszyscy dla jednej, jedna dla wszystkich / All for One, One for All, 1989, object (800 x 200 x 200 cm, 120 neon lamps, electric installation, wood, tar, cotton yare)

Wszyscy dla jednej, jedna dla wszystkich / All for One, One for All, 1989, object (800 x 200 x 200 cm, 120 neon lamps, electric installation, wood, tar, cotton yare)In his early work at the end of the 1980s, there is a visible connection between his painting and expressionist aesthetic characteristic of this period (Ręka / Hand, 1988). He also used a variety of materials, such as wood, neon tubes and ropes (Wszyscy dla jednej, jedna dla wszystkich / All for one, one for all, 1989). During this period, the artist also created monumental building-like structures, which progressively grew with new features. The best example of this was a huge installation at the National Gallery of Art in Sopot in 1993 – Wątki / Plots. Rumas built a 50-metre platform, on which he placed three water-filled pools. Each had a different theme: a glass bottle floating with a digital image of a goldfish, a harpist playing, while the third included a glowing, plastic statue of the Virgin Mary.

For the 1994 exhibition Europa, Europa, Rumas built four objects (Helicopter X 4) referring to the characteristic cone-shaped domes of the Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle in Bonn, on the roof of which it was set. Each of the cone structures, contained a steel turbine which rotated and let out tones of varying pitch.

Over time, Rumas's work dealt increasingly with social topics. The purpose of his art became the disclosure of the socio-political reality:

I feel closer is my vision of a republic of citizens, than a republic of artists. Artists should be primarily a citizen. And if he wants, a citizen, could be an artist - he once told an interviewer.

Rumas's most notorious works involve religious motifs. They attacked the religious kitsch and superficial Catholicism, thus criticizing elements of a unified Polish identity. The artist's artistic activity therefore became a "vector of minority forces", a voice fighting for a place for the Other in a society dominated by Catholics. Although his work was compared with the work of Serrano, Koons and Hirst, the artist usually rejects the influence. His work cannot be considered in isolation from the context in which they arose.

In his installation work, Rumas often used religious motifs: statues of Virgin Mary and Christ – in aquariums, combining two elements that could be found in middle-class homes at the time, fish enthusiasts and objects of religious affiliation. In Dedykacje I, II, III (1992), he placed a white and coloured figure of Christ in two aquariums. A third, in the middle, contained shells. Jerzy Truszkowski wrote that:

Submerging them in water affects their biological beauty, bringing to mind female genitalia - the same way you can never penetrate to the interior of a shell.

Religious icons and shells featured prominently in his work. In one, Weki / Preserving jars (1991-2004), he put an image of the virgin Mary with shells. The artist told interviewer Ryszard Ziarkiewicz that "In principle, the shells are a synonym for the Madonna", although "Not sexual organs, but empty ones, which are incapable of giving new life."

The same work also included another religious motif, not immediately synonymous with religion in Poland: communion wafers. The artist told Magazyn Sztuki in 2005 that although he is not a religious man, he purchased such wafers – traditionally used in Catholic masses to represent to body of Christ – to give to guests at his house. "It's just normal, with tea", Rumas said, "like Franciscan food."

At the Gesty / Gestures exhibition in Kraków in 1993, two aquariums contained figures of Mary and Christ as well as two large-format photographs of a man and a woman in underwear imitating the gestures of the religious icons.

Yet another project in 1995 saw him painting three statues of the Virgin Mary in three shades of beige with attached neon halos. The 12 Cykli Księżyca / 12 Moon cycles (2000) contains calendar pictures of half-naked women with paint reminiscent of the robes worn by the Virgin Mary. Here. Rumas seemed to imply that the church is similar to show-business, especially in a new, free-market reality.

Other works by Rumas have a more subtle religious undertone. In a series of six colour photographs Demosutra (1994/2004), the artist photographed hands against a blue sky background perform various gestures, often of prayer.

Unsurprisingly, Rumas's art and religious references were very controversial in the catholic Poland of the late 1990s. The artist held an interview in Magazyn Sztuki in 1995 that his own upbringing had an significance on his art:

It has a significance because I was of course brought up in a Catholic family. It is hard to say that it was an orthodox family, but on the other hand it can be supposed that it had the characteristics of a model Catholic family. In any case it still does in my father's case. Whereas with eroticism there were always problems. All my problems were linked with eroticism. Everything was associated with the fear of revealing my own needs and instincts. We didn't talk about this at home. My parents covered my eyes during erotic scenes in films. On the other hand, it subconsciously gnawed at me, I was frightened of it. I was really afraid of my own self, of my own needs.

Art critic Sebastian Cichocki wrote that the image of the Madonna is omnipresent in Poland, yet despite this Robert Rumas constantly and stubbornly uses the plaster statues of Madonna without any fear. "He does it with a zest of a sensitive heretic, researcher of the new ecstatic manifestation of the beauty and dazzling kitsch hunter." Cichocki concludes that "Rumas's Madonnas are treated brutally."

Unsurprisingly, Rumas's art and religious references were very controversial in the catholic Poland of the late 1990s. The artist held an interview in Magazyn Sztuki in 1995 that h