Joanna Malinowska’s interest in anthropology has been visible in a variety of her works created since she graduated from university. The artist takes on a scientific-artistic approach during the preparation process that she likes to call ‘field research’. She perceives her actions as a unique method of work, and sometimes even as an independent performative process, as a result of which, ideas for her next pieces crystalize. An example of this, is her piece In Practice (2003-2011) a compilation of short clips documenting the process of doing housework in exchange for private lessons or lectures (in one case, for music lessons). Most clips were made in response to an advertisement in The New York Review of Books in October 2002: ‘A responsible, trustworthy woman, who enjoys daily housework and will undertake any chores or similar duties, in exchange for academic lectures (especially in philosophy)’. Each clip presents Malinowska working on a prearranged task, while the lectures that she received as a reward for a job well done play in the background.

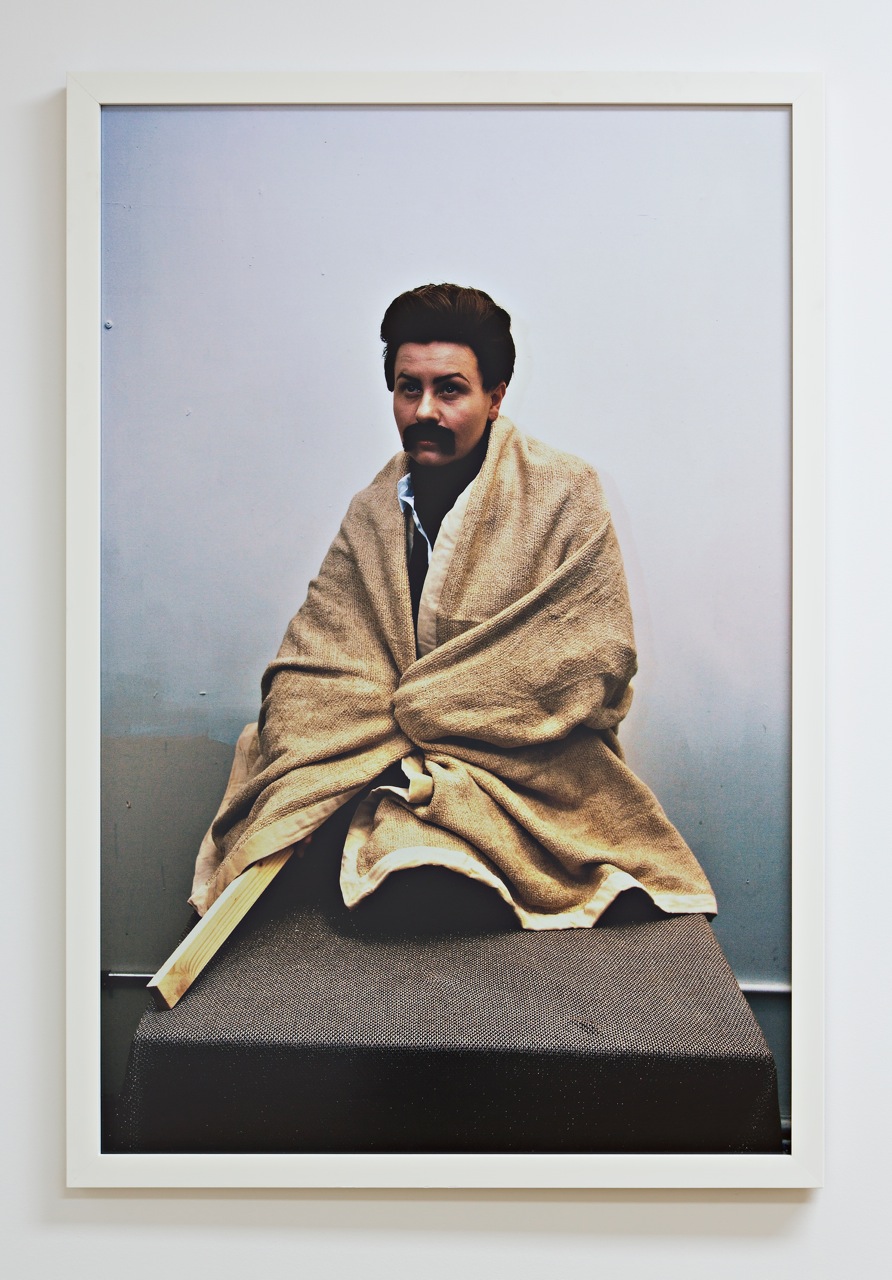

Joanna Malinowska, Self-Portrait as Franz Boas Posing as a Kwakiutl Indian Demonstrating the Draping of a Blanket for the Group Exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution in 1896, 2007, photo: courtesy of the artist

Joanna Malinowska, Self-Portrait as Franz Boas Posing as a Kwakiutl Indian Demonstrating the Draping of a Blanket for the Group Exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution in 1896, 2007, photo: courtesy of the artistIn such projects as Self-Portrait as Franz Boas Posing as a Kwakiutl Indian Demonstrating the Draping of a Blanket for the Group Exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution in 1896 (2007), the anthropological ‘method’ is a given, in terms of both the topic and the meaning of the piece. The photograph presents the artist dressed up as Franz Boas. It is a reproduction of a document in the Smithsonian’s archives in Washington which presents the American anthropologist and linguist Franz Boas. He was a pioneer of the concept of life group and individual displays, commonly known as dioramas, that are shown at museum exhibitions and World Fairs.

The piece is a humorous, yet critical glance at anthropology. By posing as Boas, Malinowska presents the anthropologist as ‘a scientific or museum subject’ in a similar way to how Boas’ imitations of members of the Indian Kwiakiutl community objectify their culture for the purpose of a museum exhibit. By copying the father of anthropology very literally, the artist aims to emphasize that the methods of presenting ‘new findings about other cultures’ are anachronistic.

Malinowska is particularly interested in the relationship between so-called primitive cultures and avant garde from the beginning of the 20th century. Her sculpture From the Canyons to the Stars that was prepared for the Whitney Biennale in New York in 2012 was made of faux walrus and mammoth tusks. It resembles Marcel Duchamp’s iconic Bottle Rack from 1914.

Joanna Malinowska, From the Canyons to the Stars, 2012,photo: courtesy of the artist and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Joanna Malinowska, From the Canyons to the Stars, 2012,photo: courtesy of the artist and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New YorkMalinowska’s newest tapestries (made of feathers) entitled Ursus maritimus (2015) and Ursus arctos (2015) draw inspiration both from Jean Arp’s artwork and Amazon tribes. Avant-garde artists from the beginning of the 20th century were exceptionally keen on looking to primitive art and folk poetics for inspiration. References to a viewpoint, not yet been touched by modern civilization is a kind of retreat to the ‘source’ of culture. While creating the previously mentioned works, Malinowska pondered what would happen if the appropriation process of indigenous works by avant-garde artists were to be reversed – for example, Hop Indians or Inuits were to use elements of Dadaism or early abstract artists’ works in their culture.

A distinct motif present in Malinowska’s art is the concept of cosmology, understood as a system of multiple contexts and references. In Search of Primordial Matter (2010), a sculpture of a washing machine that has a wide variety of content and is constantly in motion, was a reference to the Large Hadron Collider, the largest and most powerful particle collider, built by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) near Geneva. The list of ingredients placed inside includes 15 ounces of dirt from Chichen Itza, ‘a handful of nothing’ (collected in the dark after a performance by Zbigniew Warpechowski in 1973), ‘Cartesian doubt’, a dead hare passionate about art and a book entitled The Sexual Life of Savages by Bronisław Malinowski. ‘The cosmos’, encapsulated in a familiar object from everyday life, draws the audiences’ attention to the metaphysical, metaphorical and tangible references that are of interest and importance to Malinowska, as a person and as an artist.

Another example of this direction in her work is On the Revolution of Heavenly Spheres (video, 2009) or Boli (sculpture, 2009). The video presents a group of drunk male friends, each a part of the Polish diaspora living in the United States. Each has been assigned a different planet of the Solar System. The video takes places on a basketball court in Brooklyn and the men spin in circles around their own axis and around orbits that have been marked. The orbits surround a static woman, who is playing on a piano and who sets the rhythm of the drunken dance of the celestial bodies, that are also physical bodies. Malinowska’s cosmological pursuit draws attention mainly to the fact, that the Polish Diaspora is one of the possible constellations in the culturally, ethnically and religiously diverse United States.

Joanna Malinowska, Boli, 2009 (facing a replica of Malevich’s Black Square) with a mammoth tusk piercing its body, 2009, photo: courtesy of the CANADA gallery, New York

Joanna Malinowska, Boli, 2009 (facing a replica of Malevich’s Black Square) with a mammoth tusk piercing its body, 2009, photo: courtesy of the CANADA gallery, New YorkThe first version of Boli (facing a replica of Malevich’s Black Square) with a mammoth tusk piercing its body from 2009 was presented at the artist’s solo exhibition, at the CANADA gallery in New York. It is made of wood, plaster, clay, scraps of Spinoza's Ethics, Evo Morales’ sweater (the president of Bolivia) and 1 litre of water from the Bering Strait. Malinowska’s Boli is similar to a traditional object of significance to the Bamana culture in West Mali of the same name, but usually much smaller. The zoomorphic form suggests some sort of stock animal, although it is not clear which. Traditional bolis represent the Bamanan cosmos and are responsible for keeping balance in the universe. They are most often held in a special location by village elders. They are usually made of soil, blood, manure, nuts and other materials that are associated with demonic rituals. Just like with traditional bolis, its whole is more than just the sum of its parts.

Malinowska devoted herself to art, although she considered becoming a cultural anthropologist.

Eventually, I decided that what made me interested in anthropology was not so much the research that aspires to scientific objectivity, but rather the sense of relativity to a cosmic order of one’s own culture in comparison to other possible systems.

– the artist said.

A very prominent conceptual motif in Malinowska’s art is music.

Nova Benway in Ignorance, in four acts argues that "the artist often uses music – as a form of art that can both present and express the inexplicable in her work"’. In Benway’s opinion, ‘Malinowska often makes use of music in big projects, that explore the nature of knowing and also show how our perception of human knowledge, on one side undermines the attempt to understand the world and on the other hand, underlies it.

‘String Quintet for 2 Violas, 2 Cellos and a Corpse’ (2008) is a piece the artist commissioned from composer Masami Tomihisa. One of the guidelines for the piece (that revolves around death) was to use a human corpse or a body disguised as such as a musical instrument. Another musical piece that explored the nature of knowing is In Search of the Miraculous.