Lebenstein studied painting at Warsaw's Academy of Fine Arts (1948-54) under Artur Nacht-Samborski. He debuted in the period that preceded the post-1956 "thaw", during the "Against War, Against Fascism" Polish National Exhibition of Young Visual Arts at Warsaw's Arsenal (1955), showing a series of modest, nostalgic landscapes depicting the lackluster suburbs of Warsaw (Stary Rembertów / Old Rembertów, 1955). Both their subject (everyday reality) and their language reflected the artist's fascination with the art of Utrillo. Within Poland, however, they constituted a distinct, independent creative style. Recognizing this, the exhibition jury awarded the artist a prize.

Standing figure / Figura stojaca 1955; oil on canvas; 110x58 cm; courtesy of aTAK Gallery |  Hieratic figure / Figura hieratyczna, 1956; oil on canvas; courtesy of aTAK Gallery |

At this same the artist also created a series of largely unknown and uncomplicated gouaches of modest interiors (Skrzypek / The Fiddler, c. 1955). The simplified, symbol-like human figures inhabiting them announced the artist's future tendency towards deformation. In 1956 Lebenstein linked up with the independent, alternative (as we would say today) Teatr na Tarczyńskiej / Tarczyńska Street Theatre, run by writer Miron Białoszewski in his Warsaw apartment. The group was more a circle of friends than a drama troupe in the real sense of the term. Core members included the poet and his friends, above all Ludmila Murawska and Ludwik Hering. Lebenstein had his first solo exhibition on Tarczyńska, for which he created his Figury kreślone / Drafted Figures, which were followed by Figury hieratyczne / Hieratic Figures and finally by his Figury osiowe / Axial Figures. These compositions (drawn and painted) depicted vertically oriented, highly simplified human figures. The figures were centrally located on the canvas, most often female, and in the drawings resembled insect-like creatures (Figure dans un interieur, 1956). His precise, detailed, even "anatomical" drawings shared something with the art of Wols, while their pictorial values (the near autonomy he granted to material, the richness of tones in his usually narrow and seemingly unimpressive color range) placed them on par with works created at the same time by Polish artists Zbigniew Tymoszewski and Rajmund Ziemski.

The originality of this highly personal figural art formula saturated with existential fears drew the recognition of French critics, who awarded Lebenstein the Grand Prix at the First International Biennale of Young Artists in Paris in 1959. The painter immediately settled in France, though he would remain on the sidelines of the Parisian artistic melting pot. He developed a stronger link to the Polish émigré community (those at the Paris-based Instytut Literacki / Literary Institute and "Kultura" / "Culture" magazine, as well as the editors and writers of "Zeszyty Literackie" / "Literary Notebooks") than to the European or global art worlds, though his work interested such influential authors as Jean Cassou, Raymond Cogniat, Mary McCarthy, and Michel Ragon. In spite of his success, Lebenstein always felt he was an artist apart and independent. Neither did this change in 1971, when Lebenstein accepted French citizenship after residing in the country for many years.

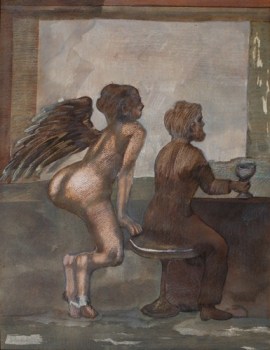

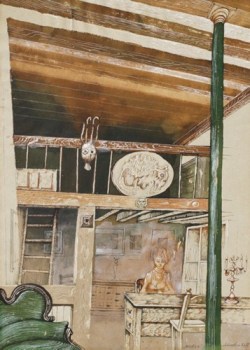

Au comptoire 1975; pastel, gouache, paper; 65x50 cm; courtesy of aTAK Gallery |  Atelier pastel, gouache, paper, 69x49 cm; courtesy of aTAK Gallery |

The artist's imagination was most strongly inspired by the great texts of world culture. He believed that the road to modernity lead through a processing of tradition. As he himself said, the cellars of the Louvre, filled with relics of the ancient Sumerian and Babylonian civilizations, fascinated him. He was stimulated by the mythologies of ancient civilizations like Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, and Greece, as he was by the Bible. This was the impulse for consistent production of works reflecting an apocalyptic vision of the world. His own "Zoology Lesson" - a personal myth about the derivation and animalistic nature of humans (Leçon de zoologie, 1972) - occupied a central place in his art. In particular, Lebenstein emphasized the biological and physiological foundations of human sensuality. A reader of cultural archetypes, he focused mainly on erotic aspects and themes (reflected in the motifs of the Great Mother and the Great Vamp) and on the concept of Thanatos, manifested in the "Isle of the Dead" motif (Lebenstein dedicated his exhibition at the Théatre National de l'Odéon in Paris to, among others, Arnold Böcklin, creator of a well-known painting of the same title). He caricatured "human fauna", creating strange creatures barely recognizable as being of "human derivation" (Carnet intime series, 1960-65). These pre-evolutionary representatives of archaic tribes were evidently subject to the pressures of untamed desires and appeared above all in Lebenstein's work after 1960 (Bottom I, Inassouvissement, both 1969).

At around the same time he created a series of paintings that portrayed "prehistoric" animals (Créatures abominables series, 1960-65) and imagined "vertebrates" (Deux vertébrés, 1966). This rich, baroque bestiary served as a bank of models from which he drew direct inspiration for subsequent works. Carefully and arduously formed, his compositions of this time seem almost sculpted in wrinkled, dough-like layers of paint, and radiant with an exceptional richness of subtle pictorial effects. Lebenstein would soon abandon this extraordinary noble material in favor of a stylization that also characterized his gouaches and temperas of the 1970s and 80s (between 1976 and 1989 the painter used no oils). These are distinguished above all by fine, often manneristic, curving lines (Animals' Sweety Bar, 1976; Asile, 1989). The works, no longer possessing the textures of his earlier oil paintings, are worthy of note for their unsettled atmosphere and tension inherent in complicated, erotic "dangerous liaisons".

In contrast to many 20th century artists, who shied away from narration in their paintings, drawings, and prints, Lebenstein not only tended towards anecdote, but was also an illustrator of literary works. His achievements in this sphere include a series of outstanding illustrations - to George Orwell's "Animal Farm" (1974), the "Book of Job" (1979), the "Apocalypse" (1983), and the "Book of Genesis" (1995). The artist also produced illustrations for a number of short stories by his friend Gustaw Herling-Grudziński. Furthermore, Lebenstein designed a stained-glass window with scenes of the Apocalypse for a Palotine chapel in Paris (1970) and dabbled in scenery design.

Before 1981 the artist had only one exhibition in Poland (1977), subsequent to which he donated a large selection of works to the National Museum in Wroclaw. During Martial Law his works were presented at exhibitions organized under the independent cultural movement, primarily with the support of the Catholic Church. In 1976 Lebenstein was granted an award by the New York-based Alfred Jurzykowski Foundation, and in 1987 he received the independent Jan Cybis Prize. He had to wait another eleven years to experience official Polish state recognition, receiving the Great Cross and Star of the Order of the Restoration of Poland from the President of Poland and an official state prize from the Minister of Culture and Art. The largest official exhibition of Lebenstein's oeuvre in Poland (a retrospective) was held in 1992, very late in the artist's career, at Warsaw's Zachęta Gallery; extensive information about his oeuvre is contained in the catalogue to that exhibit. The artist's creative path and achievements were finally summed up in an exhibition titled "Etapy / Stages", presented in Paris and a number of Polish cities in the year preceding the painter's death.

Author: Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak, Art History Institute of the Catholic University of Lublin, Faculty of Art Theory and the History of Artistic Doctrines, December 2001.

See also: Exhibition Jan Lebenstein. Demons - April-November 2005.