Before World War II: modesty and sumptuousness

In a separate article we have briefly discussed the potential of Polish cuisine, which was limited by the outbreak of World War II and then nearly completely disrupted by communism. Surprising as it sounds, before the war Poland was rich in numerous fancy ingredients, either home-grown or imported. Crayfish were so abundant that anyone, regardless of social status, could afford them. Fresh oysters, anchovies, parmesan, and chestnuts were available in delicatessen, but the truth is that many Poles weren’t able to afford goods of that sort. Some had to rely on cheap ingredients available on the market or on what they grew themselves. Authors of pre-war culinary books often focused on providing recipes for classy and nourishing yet inexpensive meals; needless to say—most Poles, especially those living in villages, lived a modest life. It’s also important to note that people respected food much more in those days than they do now—nothing could be wasted. Pre-war cookbooks also offered thrifty tips and diet advice. Authors even suggested menus which ranged from “modest” to “sumptuous”, which were even arranged according to seasonally available ingredients (which were less expensive, fresh and thus also healthier).

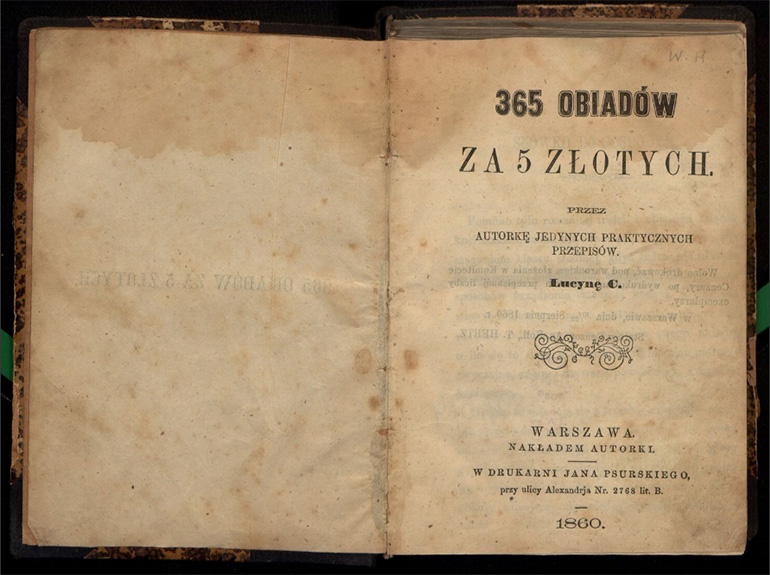

365 obiadów za 5 złotych (365 Dinners for 5 Złotys) by Lucyna Ćwierczakiewiczowa, 1860 edition, photo: Polona / www.polona.pl

365 obiadów za 5 złotych (365 Dinners for 5 Złotys) by Lucyna Ćwierczakiewiczowa, 1860 edition, photo: Polona / www.polona.plIn 1860 Lucyna Ćwierczakiewiczowa published 365 obiadów za 5 złotych (365 Dinners for 5 Złotys). The 1897 edition of the book included a recipe for a “veal-head soup which imitates turtle-soup”. And this word, imitation, will unfortunately be crucial for the following generations which had to substitute ingredients to imitate the classic meals they remembered from the past. Although turtle meat (especially canned) was available in some shops, it was likely that lots of people couldn’t afford it. Therefore Ćwierczakiewiczowa instructed on how to substitute turtle meat with popular and less expensive veal; its head in fact. Nothing was wasted, or rather, nothing but the eyeballs and the skin on the inside of the ears.

Authors tried to beef up regular, cheap ingredients as well. In Marya Śleżańska’s Co dziś na obiad (What’s for Dinner Today) there are 25 potato-related recipes and 12 dedicated to cabbage. In Marya Ochorowicz-Monatowa’s Uniwersalna Książka Kucharska (Universal Culinary Book) there are 53 ideas for cooking potatoes and 22 recipes for cabbage.

World War II: potatoes and “spit-soup”

However difficult it is to find the positives in the horror that was WWII, the creativity of Poles in terms of cooking is worth acknowledging.

Although people who inhabited Warsaw at the time recall that numerous yards had been developed into vegetable patches, living outside of Warsaw and big cities in general certainly made things a bit easier in terms of organising food supplies. Nonetheless, most housekeepers were forced to reduce their use of the most valuable ingredients, and to experiment to create “classic” meals from completely different ingredients or from lesser amounts. Maria Karpowiczowa, who spent the war outside of Warsaw, collected and rewrote dozens of recipes for meals that one was able to cook during the war, and gave it to her daughter-in-law as a gift. Próbowane i dobre (Tried and Tasty) was published in 2002 by the author’s great-granddaughter. Karpowiczowa’s recipes include “wartime doughnuts”, “Halszka’s peasant scrambled eggs for times of war”, “wartime drop scones” and instructions on how to make sufficient amounts of sour cream (to be served with blueberry dumplings) out of milk, sugar and potato flour. As she said, “the kids indulge themselves, because they can cover the dumplings with a copious amount [of the cream].”

Maria Karpowiczowa also recommended making “wartime sponge-cake” with potato purée to save on precious flour. Another example: “everyone’s favourite bean cake”, which required no flour at all:

400 grams of beans (weighed after cooking and drying)

6 eggs

6 tablespoons of sugar

A pinch of baking powder

Almond oil

Cook the beans, but not too much, dry (on a pan in an oven) and mince it (…). Beat the yolks with sugar, mix with beans, add baking powder (…) and the almond oil (…) and whipped egg whites. Bake in a moderately hot oven.

(Maria Karpowiczowa, Próbowane i dobre)

Preparation of bean cake in present times, photo: Culture.pl

Preparation of bean cake in present times, photo: Culture.plBut the one that touched my heart the most, and which is perhaps also a good example of the reality at the time, was this recipe: Korże wojenne p. Czechny / Wartime biscuits of Ms Czechna (it’s relevant to point out that those biscuits are traditionally made with poppy seeds).

You take wholemeal flour and instead of sour milk, [use] water with a spoonful of vinegar, salted and mixed with baking soda (1 teaspoon). Even without the poppy seeds, not to mention the egg. (…) fine for quick use, excellent substitute for bread when you can’t buy it with ration stamps.

(Maria Karpowiczowa, Próbowane i dobre)

The book includes numerous recipes based on potatoes, which along with yellow turnips, were probably the most common vegetable found and eaten across the occupied country.

In general, people would pick and eat whatever they could find. When there was no tea, they used linden flowers. When all they had was stale bread, they made cutlets out of it (I recently found a recipe for such cutlets on a fancy vegetarian blog under “culinary recycling” headline). They substituted sugar (sucrose) with saccharine (which was illegal before the war!).

A truck of the pre-war Warsaw-based berwery Haberbusch i Schiele, photo: National Digital Archives

A truck of the pre-war Warsaw-based berwery Haberbusch i Schiele, photo: National Digital ArchivesDuring the uprising in 1944, the situation in Warsaw became even more difficult; although the insurgents had stockpiled food supplies earlier on, these soon turned out insufficient. Although at times the insurgents were pushed to choosing extreme solutions like eating horsemeat, sometimes even dogs or cats, they often managed to seize large food warehouses. Once, they got hold of a warehouse full of tomato paste, and the menu teemed with tomato soup or pasta with tomato sauce. The insurgents also seized a warehouse of Warsaw-based brewery Haberbusch i Schiele, where they found copious amounts of sugar and barley. Barley was basis for one of uprising’s most popular soups, called zupka pluj (spit-soup), which owed its name to the fact that the cereal wasn’t husked, and its consumers had to spit the husks out while they ate.

Communism: creativity at its finest

When it comes to the period of communism in Poland, one has to keep in mind that life in a village differed from life in a city. Different periods of time had their ups and downs: in the late 40s and early 50s the nation strived to rebuild its economy, also in terms of agriculture. Even later on, things used to change from day to day. A lot depended on social hierarchy as well—the top party activists had plenty of anything they wished for. The others simply had to cope with what was available to them. Empty shelves and long queues were an intrinsic part of the Polish People’s Republic, especially in the 80s.

People selling meat on the street near Polna market, photo: East News

People selling meat on the street near Polna market, photo: East NewsThe official propaganda explained that starchy food was healthier than meat; the truth is that the authorities tried to make up for the regular shortages of meat (and other ingredients) and to root out society’s gourmet instincts. Food was portrayed merely as fuel. Nonetheless, society managed to organise meat, other than luncheon meat, on its own. In spite of agriculture collectivisation, some small, family-run farms still operated. Friends, relatives and the more accidental consumers (grapevine being the key word) would (illegally) buy meat and other products from farm owners.

However, meat served in restaurants and bars wasn’t to be trusted either; a classic steak tartare is made of finely chopped, high-quality sirloin. But due to a lack of particular types of meat at the time, tartare would be prepared from chopped pork dyed with beetroot juice.

How else did people deal with these constant shortages? Well, some would pickle Mirabelle plums, which grew wild—these were called “Polish olives”. Others made cutlets out of mortadela (which wasn’t even close to the Italian mortadella sausage) cut into thick slices, then crumbed and fried.

Making of mortadela cutlets: mortadela slices, an egg, some flour and bread crumbs, photo: Culture.pl

Making of mortadela cutlets: mortadela slices, an egg, some flour and bread crumbs, photo: Culture.plI even found a recipe for mayonnaise made of powdered milk and a recipe for home-made champagne.

1 litre of whey

10 grams of yeast

2 tablespoons of sugar

20-50 grams of raisins

if possible, lemon or orange zest

Indeed it wasn’t easy to get ones hands on an orange in any time of the year other than Christmas.

Mix yeast with sugar, cover with whey, put in a warm place. After around 12 hours pour it to tightly sealable bottles (…) add a few raisins and some zest to each (…). Store in a cold place, drink after 2-3 days.

(Błażej Brzostek, PRL na widelcu)

Some of my family members also recall the Kuchnia Chińska (Chinese Cuisine) book written by Katarzyna Pospieszyńska. The book advised on how to cook Chinese meals without original ingredients. Some tips supposedly included using Maggi stock diluted with water instead of soy sauce or celeriac and kohlrabi instead of bamboo shoots.

Many people claim that there was a certain difficulty in obtaining real coffee; it is true, if you don’t consider instant coffee as “real”. The authorities imported some coffee from Brazil, however, its price (out of touch with reality) and instructions regarding the amount of coffee that cafés were supposed to use (60 grams per 1 litre of water) made coffee an object of true desire. The ladies who worked in the coffee shops often made coffee with even less than the instructions required, and thus managed to keep some for themselves. They would often hide it in a jar and take it home. Some say that roasted grain beverages (grain coffee in the Polish People’s Republic was made of roasted barley, rye, chicory and beetroot, and had nothing to do with coffee) were “invented” to substitute for inaccessible real coffee, but recipes for home-made grain coffee were already being printed in pre-war culinary books. Regardless of the truth—in comparison to real coffee, there was plenty of mass-produced grain coffee around.

Now and then: a few words from Adam Chrząstowski

Adam Chrząstkowski, photo: Flesz

Adam Chrząstkowski, photo: FleszWhen I was researching this article, I decided to contact Adam Chrząstowski, one of the most esteemed Polish chefs, who was the Chief Culinary Consultant during the Polish Presidency of the European Union in 2011. He was the head chef and co-owner of the successful and celebrated restaurant Ancora in Kraków. The restaurant has been awarded by Michelin for 6 years in a row. In 2014 Chrząstowski left Ancora and opened Ed Red, a steak house, which after receiving a "fork and spoon" Michelin designation, made its debut in the 2015 Michelin Red Guide. Adam Chrząstowski guided me through the realities from his professional point of view.

ADW: What kind of culinary experiments from the time of communism do you remember?

Adam Chrząstowski: We must divide all that happened into two groups. One was creative indeed; in gastronomy and in households people invented ersatzes, substitutes of what was a standard before the war, so, for example, the infamous chicken a la tripe, was a creative use of poultry pelt (…)—this soup theoretically tasted like tripe. Or the tripe-like soup made of oyster mushrooms, which resemble tripe when chopped.

Due to the common lack of meat, at least of its better types or parts, people sought for substitutes. It’s not that bad if someone cooked pork with wine, juniper and herbs and called it venison, as it was associated with the forest, wilderness. It was worse if meals were an evident fraud, like tartare, supposedly made of sirloin.

It was an interesting phenomenon that at some point in the PRL, those ersatzes and substitutes displaced their prototypes, those standard classics. The nowadays standard kotlet schabowy (breaded pork cutlets) is an absolute substitute for the classic Viennese schnitzel. The nomenclature often exhibits examples of meals that, due to numerous reasons, evolved from a standard or classic dish. Take the classic kompot for example—in Poland it functions as a sweetened fruit brew—something that we drink. But the starting point for this drink was the French compote, where whole pieces of fruit are braised in a little amount of water—water makes the sauce—but the whole purpose of compote is the fruits.

That has shed more light on my culinary knowledge indeed. But the truth is I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t enjoy a glass of kompot! So I asked whether the ersatz cuisine generated other surprisingly good effects.

AC: It depends on the perspective. If someone tried to take a shortcut and only wanted to obtain acceptably tender meat, they started to add marinates, softeners, which completely changed the basic flavours of those meals, and in consequence, people tended to forget the taste of a real roast. In fact, there were situations where the whole point was to marinate the meat to completely change its flavour. We can even take a piece of wood and marinate it so it tastes how we want.

I had the pleasure of visiting Chrząstowski’s Ed Red in Kraków. The restaurant bases its dishes on fresh, local ingredients. Each meal has its own individual twist. I wondered whether the difficulties of communism affected his preferences in terms of cooking.

AC: I was lucky; in the 70s, when my peers indulged on canned ham and “Pepsi Cola”, I partly grew up in Kurpie and Góry Świętokrzyskie. During the holidays I would catch partridges, fish, crayfish, various things I was able to spot. My uncle hunted for venison—I knew what to do with it. They were able to be self-sufficient. People had orchards, animal husbandries.

But in the 90s, when the Bristol Hotel reopened in Poland, we had a visit from foreign, western chefs. They said, “we have to treat you like tabula rasa”. Many of us had to extirpate communist habits and learn how to cook all over again.

I also wanted to know what culinary creativity in Poland is like nowadays, if it’s just about proving that Polish cuisine is more than bigos and pierogi. From the perspective of Adam Chrząstowski, and myself, contemporary Polish cuisine at its finest results from appreciation of our local goods.

AC: To me, it’s knowing that there are plenty of exquisite Polish products; Poland is, in comparison to other European countries, not as industrialised. There are many products that significantly differ from the products of other countries.

When I acted as the Chief Culinary Consultant during the Polish Presidency of the European Union, and I trained chefs to cook “in Polish”, I took a Polish guinea fowl to Brussels. We baked a Polish guinea fowl in one oven with a guinea fowl bought on the local market [of Brussels]. No one believed these were the same birds, as they tasted completely different.

We have products not only tastier, but ones that tell a lot about Poland’s character. One can easily create own ideas. Let’s play with it, let’s joyfully compose meals for our guests, in the best way that we can.

Chrząstowski confirms the words of 19th-century author Lucyna Ćwierczakiewiczowa, who concluded in the preface to 18th edition of 365 obiadów za pięć złotych:

I believe it’s important to add that freshness and choice of fine supplies is the first rule of fine cuisine, because nothing good can be made from poor items.

As a nation we might have struggled to savour the best of what Poland has to offer, but now that we no longer look at the west with jealousy and access to food is not restricted by anything, when shop shelves bend under the weight of goods, it’s time to play around, mix and match local Polish ingredients, perhaps look back at our roots, and simply—enjoy Polish cuisine all over again.