Agnieszka Sural: Do you speak Polish?

Anna Bella Geiger: When people ask me if I speak some Polish, I have to say that I don’t. Probably because my mother learned Portuguese very quickly. My parents spoke in Polish when they did not want me and my sister to understand what they were saying. I only knew that these were familiar sounds. I had never been to Poland before, but when I hear someone talking, I know if it’s Polish. Usually my parents spoke in Yiddish, which I still understand well. As immigrants, step-by-step, they spoke more and more in Portuguese.

AS: Where were your parents from?

ABG: My father was born in Łódź and my mother in Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski, where they both lived with their families and got married. My father’s name was Waldman. And Juwen was the original name of my mother. In 1922, he immigrated to Rio de Janeiro, the capital of Brazil at this time. And after him, came my mother. A cousin and a brother of my mother also came to live in Rio de Janeiro. But all the rest of the family stayed in Poland, they were not able to come.

In Poland, my father was a leather craftsman producing women’s handbags. He belonged to a socialist bund for workers. When he came to Rio de Janeiro, he brought a case full of those handbags. Several have been well preserved. I always loved them. They are still very fashionable, in the Art Déco style. I exhibited them in my first exhibition in Poland – organised in April 2017 by Paulina Ołowska and the Pamoja Razem Foundation, in Kraków.

When my father came to Rio, he worked in various leather factories. One day he had the idea to learn how to cut and sew women’s clothes. He was a good craftsman, like an artist. In 1945 he opened a store for women fashion, haute couture dresses. He sewed very sophisticated clothes. The store was called Ninon Modas. Modas means fashions. He and my mother kept this store for almost 30 years. He closed it in the 1970s, when there was a new urban plan for Rio and construction of the subway took over the area. Most of the old houses around were torn down. The house where we lived too. My father kept working at our new home

Father Leather Handbag by Anna Bella Geiger, photo: courtesy of the artist

Father Leather Handbag by Anna Bella Geiger, photo: courtesy of the artistAS: Have you cultivated Polish tradition at home?

ABG: When I was a child, my mother used to cook our food. So I knew that it was Polish recipes like the smashed potatoes, borscht, beets, kasza, kreplechs, horseradish, mushrooms in soup – that once in a while my grandmother used to send to us as well as kasza. It wasn’t easy to find kasza in Rio at that time! My father liked to cut some folding objects out of paper and he also used cans like miniature toboggan sleds, and large flowered paper mandalas. He also made large paper covers for lampshades. This is very Polish, I imagine.

When Paulina Ołowska invited me to put on a performance during the third edition of her Mycorial Theatre project, which took place in 2016 at the Pivô Institute in São Paulo, my Polish roots were still unknown to her. After the project, she sent me Polish dried mushrooms. I cried so much when I opened the package. Mushrooms were the last thing we got by mail from Poland, in 1939, sent by my dear grandmother. After that we lost all contact with them, including with my younger aunts.

AS: Do you feel Polish?

ABG: In part, yes. But no more than Brazilian. Our first home in Rio, where we lived for 20 years, from when I was born, was a large two-storey house located in an area where many poor family of immigrants from Portugal, Italy, and Germany lived, including the black population of Rio. And we were Jewish from the low middle class. We used to get along very well with our neighbours. There were also a few Polish families who had immigrated from Ostrowiec, but they lived far away, in the favelas of the suburbs. My way of dealing with this mélange of people of such diverse origins, since I was a child, gave to me in some sense, a large feeling of tolerance towards others. I studied at the Lycée Français of Rio de Janeiro, where I could notice differences in behaviour in the French students.

View from Anna Bella Geiger's exhibition What Was Inside That Leather Case? in Kraków, April-May 2017

View from Anna Bella Geiger's exhibition What Was Inside That Leather Case? in Kraków, April-May 2017AS: Your art teacher also came from Poland.

ABG: I started to learn art with a Jewish Polish-German teacher when I was 15. Her name was Fayga Ostrower (her maiden name was Krakowska), and she was born in Łódź. She was a war refugee. She didn’t know Polish because her family left Poland very early to live in Germany, much before fleeing to Brazil in the 1930s. So she spoke German. In 1949, her brother married my older sister.

Ostrower became one of the greatest Brazilian artists. In 1958 she sent her abstract woodcuts for the Venice Biennale competition and she won the most important prize. A Polish-Jewish woman wins the International Prize for Brazil at the 29th biennale in Venice! I studied in her studio for four years. Then I went to the university and I studied philosophy, linguistics, and Anglo-Germanic languages.

Fayga’s work at that time was turning from the figurative Expressionism into Abstraction. She discussed art with a socialist ideology. She took it on her way. One day she said to me: ‘Let‘s go to paint and draw the people living in the favelas, up on the hills’. It was in her neighbourhood. We went there and we drew mainly women working and their children. ‘Do not copy, try to feel these women with their children. Depict them with dignity’. I accompanied her work while she was developing her own abstraction. It wasn’t so hard for me to forget the figurative, but for her – yes. She had to fight against others in the artistic Brazilian academic scene of art to become an abstractionist. So this was my school – for me as an artist and as a teacher too.

In 1968, I was invited to teach at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio. I also had a small atelier at home, and a printing press that I still use. I started to teach drawing and metal engraving. Some classes started with ten people and ended with two. I was very exigent and I still am. I never liked to teach technique in itself. I am more interested in the conceptual analysis of the works. Now, I have been teaching once a year at the Higher Insitute for Fine Arts in Ghent, Antwerp, and in the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage in Rio. I have already given lectures in the School of Beaux Arts in Beijing, China, at the MoMA NY, at the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art, Paris, among other international institutions.

Untitled by Anna Bella Geiger, 1964, photo: courtesy of the artist

Untitled by Anna Bella Geiger, 1964, photo: courtesy of the artistAS: Why didn’t you come to Poland before?

ABG: Travel to Europe was and still is very expensive. My works were not considered art at that time (the 1950 and 60s) within a more commercial art market that existed here. And also in part due to our terribly political years of dictatorship. I have a large family, a husband and my four children to support, and also my parents. It was my duty to take care of them, when they were alive. From the 1960s on I could in some way start to live off my work, especially from the etchings and as an illustrator. But to survive is not to afford a plane ticket. Also, for the diverse circumstances I had been invited during all these years and up to now to other countries in Europe.

Then, I started to receive some prizes abroad, like in 1963 when I went to Havana in Cuba. I got the award from the Casa de las Américas for my abstract etching. I was invited to go there and receive it from the hands of Fidel Castro. I was afraid because I had never travelled by aeroplane before. In the 1950s, when I went to New York, I did it by ship. Then, in 1969, I came for two months to Europe as I’d received the International Prize from the MoMA RJ. I went to France, Holland, and England to see galleries and museums.

There was a famous Brazilian art critic, Mário Pedrosa, who loved Poland and also Prof. Walter Zanini, the director of the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo, who used to travel to Poland and to former Yugoslavia. He organised exchanges between artists from Eastern Europe and Brazil. I met these people in 1980 when I took part at the 39th Venice Biennale. It was my second visit to Europe.

Brasil Little Boys & Girls by Anna Bella Geiger, 1975, photo: courtesy of the artist

Brasil Little Boys & Girls by Anna Bella Geiger, 1975, photo: courtesy of the artistAS: The military regime that ruled Brazil from 1964 until 1985 was a difficult period for the Brazilian art scene. There were severe political repressions against artists. Did the dictatorship affect your art?

ABG: Besides being an artist, I always took part in political discussions in Brazil. The discussions were not about the politics of the state but the politics of art and the system of art in itself. The main changes occurred in my work. From the early 1950s to the middle of the 1960s, I worked as an abstract artist, mostly on drawings and engravings, and some oil paintings. Then, as a turning point, I was deeply inspired by the human body and its organic forms. For four years I worked mostly on images based on the functioning of our organs like brain, heart, liver, and throat.

For a living, I illustrated books, children’s books, dictionaries, and book jackets. One of the first works I did was an encyclopaedia of geography. It influenced me. I always liked historical maps. And, as a child, I always asked my sister to show me the map of Poland and the city of my mother. My husband, Pedro, is a geographer.

Cartography is a political instrument and I try to explore among other things the ideological possibilities of the maps. A critic wrote that my use of the geopolitical is ‘geopoetic’. In the 1970s I did some conceptual works, using postcards, Xerox copies, and photography as media. I also made artist’s books and I was the first artist to start to use video in art in Brazil in 1974.

AS: Did you ask yourself where you could go as an artist in that political situation?

ABG: In the beginning of the 1970s I felt such disenchantment and unhappiness. Looking from now I can tell that the crisis was also about my own doubt and discussion on: what does art mean? What does an object of art mean? Its nature? Its function? I had these questions. My feelings at that time were very uncomfortable. When you are not interested any more in using paper, ink, etching, canvas, any support of art, and you don’t care anymore about it. I didn’t feel as if I was abandoning it, but also I didn’t find any motif to continue doing what I did before.

I reflected on it only with myself, I was quite alone. Then I met other artists more like me. As a teacher I felt a great responsibility towards my students, to whom I had to transmit my understanding of the situation, if I only could express it… At that time, in 1975, I met Joseph Beuys and we made a video together.

Still, the very beginning of the 1970s was the most difficult moment. Why was I ‘abandoning’ the use of paper that I loved so much? What was happening? I knew etching, painting, and drawing so well! I stopped ‘working’ for a while and read more about anthropology, tribal behaviours, the origin of Man, etc. In the early 1970s the Earth, terra, the land – became for me the only authentic support for art. I took my students to a deserted forest with a lagoon, not far from Rio. I invited my friend, photographer Thomas Lewinsohn, to record in pictures, transparencies, whatever we were doing or working on, using tools proper for digging, excavating, as rakes, forks, etc. He accompanied me for three months during my experiments. I still have the results on slides. And they became an exhibition occupying the whole Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro. I called it an environment and entitled it CIRCUMAMBULATIO.

In 1969, my husband was invited to teach at Columbia University in New York. He writes about Marxism and geography. We moved with our family. This trip was important for me and for the children too. I took my works with me and I met Dore Ashton, the main critic at that time writing about abstract artists. But I had to come back to Brazil before my husband because it wasn’t easy to live with four children in New York.

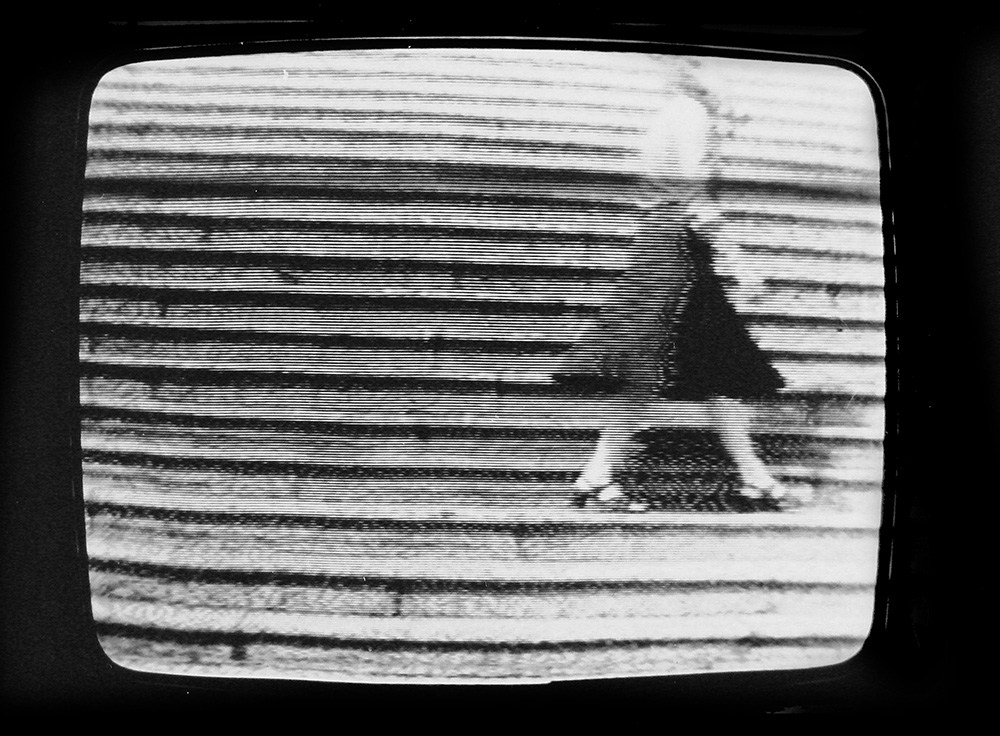

Still from Passagens I by Anna Bella Geiger, 1974, 13 min, P&B câmera J. T. Azulay, photo: courtesy of the artist

Still from Passagens I by Anna Bella Geiger, 1974, 13 min, P&B câmera J. T. Azulay, photo: courtesy of the artistAS: The military regime made you boycott the 10th São Paulo Biennale too, in 1969.

ABG: The most difficult moment was in 1968. The military dictatorship decreed the very repressive Institutional Act no. 5, suspending political and civil rights. For artists like me – who had been taking part in the International São Paulo Biennale since the beginning of the 1960s – it was hard to receive and edit, with a decree distinguishing what is forbidden and what is allowed in art. It said it was forbidden to send works on political or pornographic issues. Intellectuals and artists that stood against the government and its law were persecuted. We, some visual artists from Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, met in secret at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio. We decided then to boycott the biennale and all other art institutions. Our names weren’t written in any document, but we were committed to it. We informed as we could artists from abroad and explained our situation to them. They supported us and didn’t apply to take part in the biennale. It was an international protest – it gained solidarity from Europe and the USA. But it was terrible not to take part in the biennale.

In 1968, there was the second edition of the Arts Biennale in Salvador, Bahia. I showed my works there and got the prize. But this biennale closed two days after opening. Some of our artworks were considered subversive and were confiscated. I showed there some of my works of the visceral phase – parts of the body.

AS: Why was it terrible not to take part in the biennale?

ABG: Because, for us, it was the only window to the world. The boycott lasted 22 years. The biennale reopened in 1981 but the regime had not yet ended. We, the artists who kept up to the end, compromised the boycott. Let’s say that ‘we shot ourselves in the foot’. But what could we do? For more than 20 years we were surrounded by the most terrible desertification of information. In 1974, I started to make videos. One of the first, Statement in Portrait, is a political statement. In this video I say that some artists – but I don’t say exclusively about dictatorship – some of us are going to change the situation. Surprisingly, it wasn’t censored. There were different degrees of prohibition.

In 1975, I created several little books entitled History and Geography of Brazil. I exhibited them in one of the galleries in São Paulo. Someone must have told the police to go and see the exhibition, because I received there a couple of strange people who asked me what these books meant. I improvised and I said that I liked to imitated children’s books and their writing.

AS: What was the real meaning?

ABG: One of the little books I called Admissão (1975-77). Admission is when children pass from primary to secondary school. They take a test. I took a prepared geography exam, erased and transformed some of the questions and answers into our political context of that time. It is to love or to cry about. This book is a little tragic.

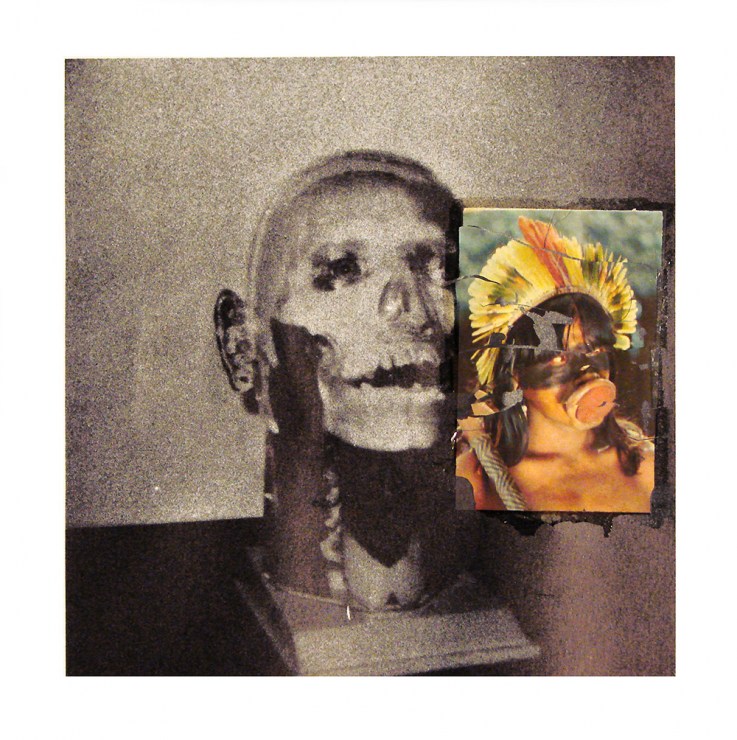

Photo from the series Native Brazil / Alien Brazil by Anna Bella Geiger, 1976-1977, photo: courtesy of the artist

Photo from the series Native Brazil / Alien Brazil by Anna Bella Geiger, 1976-1977, photo: courtesy of the artistAS: After the exhibition of your works in Kraków, Native Brazil / Alien Brazil went to the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Your first ever piece in a Polish collection!

ABG: It was a gift by the Razem Pamoja Foundation. I am very pleased with that donation. I did this work in 1977, during the dictatorship, when I saw some postcards of Brazilian natives in beautiful, utopian scenes being sold in newsstands. The images were not false, but not true either. On the back of the postcards, the image subtitle credited them as native Brazilians. Anthropologically, it was correct. But I asked myself: where are the others? The Caucasian Brazilians like myself, the mulattoes, the caboclos, the mamelucos? In Brazil there are all sorts of mixed ethnicities. I guess that the idea of the regime was to show that they were protecting our natives, that the military regime was preserving our Indians. So, I started to make cultural analogies using other kind of photos as postcards. At that time, some critics of art criticised these work of mine as nonsense. By now, 41 years later, this series of 18 postcards is more and more understood. Now they belong to the main museums and private collections in Europe and America.

In the series Native Brazil / Alien Brazil, there are nine pairs of pictures comparing Brazilian indigenous men and women with me and my family. Originally, there were 20 pairs! I previously censored them myself. For example, I didn’t include one of the works where indigenous are watching a military parade on television and myself watching indigenous’ men dancing on a TV programme. It was too dangerous to include it at that time. On the reverse of each postcard I printed a phrase saying that I am not trying to be or to make believe that I want to be like the Indians, or to be able to imitate them. I wrote: ‘… with my lack of skill as a primitive man.’ I wanted to say that at that specific political moment they had no rights as citizens as well as us, all the ‘other Brazilians’. In the 1970s the Indians were still very marginalised. Now, we can notice that their situation, with special programmes for health assistance, schools, has improved a little bit, respecting more their own identities. It is changing for the better.

Interview conducted in Kraków, 27 April 2017