Nine years later than Pierre Schaeffer's experimental studio in Paris, six years later than Cologne's Studio für elektronische Musik and two years after Milan's Studio di Fonologia Musicale, the Polish Radio Experimental Studio began operating in 1957. The fourth European experimentally-oriented radio unit spurred on an era of electroacoustic music in Poland. Until then, the only signs of the upcoming current were found in the film and theatre scores of Andrzej Markowski and Włodzimierz Kotoński.

For 28 years, the studio was headed by its founder, the musicologist, sound engineer, animator of musical life and later president of the Association of Polish Composers Józef Patkowski. Composer Ryszard Szeremeta managed it between 1985 and 1998, followed by Krzysztof Szlifirski between 1998 and 2004, who was also responsible for the technical concept of the studio. In March 2004, the Experimental Studio was incorporated by Channel 2 of the Polish Radio and its role is carried on by Marek Zwyrzykowski.

The Beginning: Study For One Cymbal Stroke and Microstructures

The proverbial "strike of the cymbals" which opened a new chapter in the history of music in Poland was Włodzimierz Kotoński's Etiuda na jedno uderzenie w talerz (Study for One Cymbal Stroke) from 1959. It was the first piece composed at the Experimental Studio and was the soundtrack to the surreal animated film Albo rybka...(Or the Fish) by Hanna Bielińska and Włodzimierz Haupe. The visual atmosphere is aurally mirrored by a strike of a medium sized stick on Turkish cymbals. The film score was then developed into the first autonomous Polish piece of music on tape.

Włodzimierz Kotoński, source: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne

Włodzimierz Kotoński, source: Polskie Wydawnictwo MuzyczneThe technological process employed for the creation of the piece connects two different composition techniques: serialism and musique concrète. The former was authored by Arnold Schönberg, who in his pieces formulated and used dodecaphony. The idea was picked up and further developed in the concept of total serialism by Anton Webern.

The Austrian composer posited a schematic organization of pitch, rhythm, dynamics, tempo, tone and articulation. An entirely new manner of composing music was put forward by Pierre Schaeffer in the mid-20th century. His pieces utilised all surrounding sounds: set and encountered matter usually considered as noise and murmur - recorded, processed, and sorted according to the assumptions of a given piece. The French artist brought concrete, palpable sound events which are recognised from the first hearing into the sphere of musical art. Magnetic tape, editing techniques, the search for new sounds and expression turned Schaeffer's "noises" into experimental music. The form was called 'concrete' by contrast to music that was first concocted in the head of a composer and then transcribed into a score.

Introducing the first performance of Schaeffer's Concert de bruits on the French National Radio on October 5th, 1948, the radio host quoted the man of the hour:

Let's open our ears, equipped with precise instruments for enlarging, speeding up, slowing down, unlike the eyes, which require a microscope. […] It turns out to be impossible to strip sounds of their dramatic nature, of their capacity to create moods and symbolic meanings. No effort can impose on them an abstract quality.

But musical tradition kept having a strong hold on the innovators. The first compositions of the Experimental Studio of the Polish Radio were published in the form of scores. Włodzimierz Kotoński's Study For One Cymbal Stroke was among the pieces brought out by the publishing house Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne.

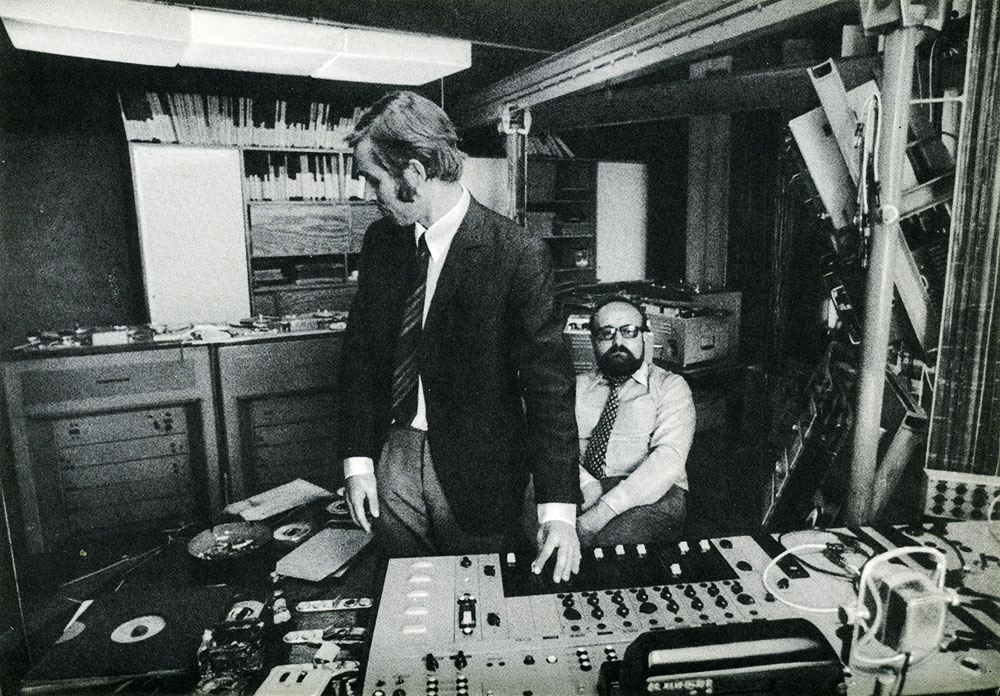

Krzysztof Penderecki and Eugeniusz Rudnik at the Experimental Studio of the Polish Radio, April 1972, photograph from Ludwik Erhardt's book "Spotkania z Krzysztofem Pendereckim" (Meetings with Penderecki)

Krzysztof Penderecki and Eugeniusz Rudnik at the Experimental Studio of the Polish Radio, April 1972, photograph from Ludwik Erhardt's book "Spotkania z Krzysztofem Pendereckim" (Meetings with Penderecki)Filters were employed to convert the sound of the cymbals into six bands of different widths and then transposed into eleven heights. The technique was carried out in a strict manner, making use of scales. One had eleven scales and sorted the samples according to length, another had the same number of scales and was dynamic and yet another had six scales and differentiated articulations.

Traditional sound matter was torn away from its instrumental source. What was left, however, were elements of composition written on the staff in the form of a score.

Whether the innovators were planning on going through with their ideas differently is unknown. If that were the case, it would mean that they felt the need to leave space for interpretation. The plan to create new sound versions of those historical scores is coming to fruition.

Microstructures from 1963, Włodzimierz Kotoński showed a similar approach to composition. Unlike Study For One Cymbal Stroke, Microstructures was devoid of illustrative substance. The piece was built from recorded sounds of strokes on glass, wood and metal objects cut into very short centimetre long fragments containing an attack and a part of the reverb. These particles, the micro ingredients of a sound puzzle, were then mixed and randomly put together in slightly longer sections. The sequence was copied, sometimes shortened and assembled together into loops of irregular lengths.

Four to eight pieces were later matched together into one layer, thus creating a "micro structure", a type of "sound cloud" (as the composer called it), vibrating on the inside, dynamic, containing from a dozen or so to several dozen occurrences per second. Much like in the earlier Study ..., the structures were also transported into different heights. It was through tests and trials that they found their place in the over five minute long piece. Ergo, all the complicated compositional procedures underwent a largely spontaneous auditory judgement.

There are subtle technological differences between the making of Study... and Microstructures. For the former, elements of a highly accurate and rather traditional dodecaphony technique (which made use of traditional instruments) were used. The method of the latter meant avoiding any type of sorting the material, resorting to spontaneous creation instead, though analogies to writing on staves can still be made.

There was an aleotoric element to it. In the case of composition for tape this "controlled" aleotorism or chance required the pre-selection of sound structures at a certain stage of their sorting. Another possibility was to base the creative process on trial and error which promoted the search for emotions, moods and messages in the abstract sound form. Microstructures did just that.

Made of noises: Dobrowolski's Passacaglia

Andrzej Dobrowolski, author of two flagship compositions of the Experimental Studio: Muzyka na taśmę magnetofonową i obój solo (Music for Magnetic Tape and Solo Oboe) from 1965 and Muzyka na taśmę magnetofonową i fortepian solo (Music for Magnetic Tape and Solo Piano) from 1971, also composed Passacaglia which shows the extent to which traditions were still entrenched in the composition techniques of the pioneers of electroacoustic music.

Passacaglia is a musical form with a recurring melody in which the bass repeats the same harmonic pattern throughout the piece. The rest of the composition is an assembly of variations of that thematic structure. Andrzej Dobrowolski attempted to build an exact Baroque structure from bruitist materials which were different kinds of noises.

The piece derived from the score to a play by Maria Konopnicka called Szkice z przeszłości (Sketches from the Past) performed in a theatre in Białystok in 1960. Its starting point was five drum noises which were recast into a collection of forty quasi-percussive occurrences which could not longer be associated with their initial instrumental nature. The samples were given different rhythms, they were placed on an frequency axis and transposed by changing the speed of the tape for example.

Andrzej Dobrowolski's Passacaglia is subtitled "for forty out of five", a reference to the five initial drum noises from which forty sound objects were derived from.

Electronic psalm: Penderecki's Psalmus 1961

Electroacoustic music differs from traditional instrumental and vocal pieces but also espouses their creative process in its own. Krzysztof Penderecki's Psalmus 1961 is a perfect example thereof.

Krzysztof Penderecki in Dębica, 1969, photo: Wojciech Plewiński / ForumAmong the composer's best known pieces are Psalms of David for mixed choir, string instruments and percussion (1958), Strophes for soprano, voice (reciting) and ten instruments (1959) and Dimensions of Time and Silence for mixed choir of 40 voices, strings and percussion (1959-60). Some of his pieces were purely instrumental (Threnody and Anaklasis) but the vocal element, which would later become the dominating element of the oratorical works, was already strong. Psalmus 1961, the only autonomous and non-illustrative piece also had a clearly noticeable vocal element. Earlier, the Experimental Studio developed the composer's film scores and in time he created the three minute long Ekecheiria which was played at the opening of the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich.

Psalmus 1961 arose from spoken or sung vowels and consonants of different length and intensity. With a rich selection of sounds, the composer used a drafted score as a type of ideogram. Much like Kotoński's Microstructures which would appear two years later, the definitive piece resulted from spontaneous disposition of the sound material, a process of sorting of the edited, transposed, and filtered material.

Two things can be said of the work. On the one hand it is an expression of the composer's interest in the new media, on the other, it reveals his attachment to tradition. The title - Psalmus 1961 - indicated the contemporary technological context in the centuries-long tradition of psalms in music. Another idea that Penderecki relocated into instrumental music was the underlining of clusters in the score.

One of two sources: Dobrowolski's Music for Tape No 1

When it comes to the first works of Włodzimierz Kotoński, Andrzej Dobrowolski and Krzysztof Penderecki, the starting materials were homogeneous – a set of strikes of a medium sized stick on Turkish cymbals (Włodzimierz Kotoński's Study For One Cymbal Stroke), sounds of strikes on glass, wood and metal objects (Włodzimierz Kotoński's Microstructures), five percussion sounds (Andrzej Dobrowolski's Passacaglia), sung or spoken vocal sounds (Krzysztof Penderecki's Psalmus 1961).

Other compositions created in the Experimental Studio came to life on starting material of varying sources. Andrzej Dobrowolski's Music for Tape No. 1 is a good example. It had four sources: the sound of electronic generators, piano chords, sung sounds and resonating piano strings.

What was felt since the very beginnings of electroacoustic music was the need to cut back on the amount of audio material. In Music for Magnetic Tape and Oboe Solo from 1965, Andrzej Dobrowolski did exactly that. Not all the oboe sounds were made by playing it. What was also used was the beating of tabs and unconventional blowing. It was the wood and metal from which the oboe is built and the acoustic effects that brought musical value. The solo layer was the domain of the classic-sounding oboe.

Combining the oboe and tape, and the piano and tape later on (the aforementioned Music for Magnetic Tape and Solo Piano from 1971) with the use of virtuoso tenures for both pieces is but another expression of constant references to tradition - the concepts of performing in concert in this case. In Andrzej Dobrowolski's piece, the oboe can be active and explicit but also lyrical and pastoral as its nature dictates.

It's perhaps no coincidence that poly-sounds started to be introduced to the oboe technique at more or less the same time. This attempt to overcome the erstwhile perception about its possibilities was undertaken by Witold Szalonek in Four Monologues for Solo Oboe from 1966. Dobrowolski's actions were different. For Music for Magnetic tape and Solo Oboe he juxtaposed the layer of tape with the classically played oboe.

Towards radio documentary: Rudnik's Collage

From the beginning, the Experimental Studio of the Polish Radio sought to introduce composers to technology through so-called "guides". This is where the engineer Eugeniusz Rudnik and the sound director Bohdan Mazurek came into play. The former started working for the Experimental Studio in 1957, the latter in 1962 and they both began dabbing with their own compositions early on.

Eugeniusz Rudnik, still from "15 Corners of the World", photo: Ula Klimek / UNSOUND'12 / www.15corners.com

Eugeniusz Rudnik, still from "15 Corners of the World", photo: Ula Klimek / UNSOUND'12 / www.15corners.comEugeniusz Rudnik was not educated in the art of classical composition and thus saw the wide spectrum of possibilities offered by the technology of the Experimental Studio. One of his first works was Collage from 1965. The composition was based on the electric hum of the amplifier of a Telefunk lamp console. He commented on the project in a radio show,

It's the overblown music of the apparatus on which I performed all those precise, squeaky clean, sterile sounds. If you open the muffler a little wider, the console starts to whirr and tremble. There's a pulse, there's the subconscious gurgling of the blood in the arteries and veins which we don't hear on a daily basis. You have to close the human in an insulated room to make him hear himself. I recorded that soul, that pulse, that filth, that misfortune of the engineers and called it my work. I gave it a title and said: this is Eugeniusz Rudnik's composition. It can be classified to the great big branch of bruitism, the music of buzzing sounds, rotten materials, music made from non-precious sounds.

That was not the sole component of the composition. What becomes recognisable are characteristic mid-60s radio broadcasts: dance music and a statement by a blasé civil servant expressing the country's concern about the economic situation. Eugeniusz Rudnik used those elements creatively and critically towards the regime.

Schaeffer's Assemblage

Even the most avant-garde composers still yearned for the possibility to interpret music through instruments. Bogusław Schaeffer's Assemblage (joining, filling, mixing in French) brought together edited and sorted previously recorded pieces on the violin, the piano played by the artist himself. And so, instrumental sounds found a lasting place at the Experimental Studio. Assemblage is an anti-thesis of Electronic Symphony, created at the same time. What contrasts the two pieces is the role of the sound engineer. Schaeffer comments,

Bogusław Schaeffer, photo: Eugeniusz Helbert / Forum

Bogusław Schaeffer, photo: Eugeniusz Helbert / Forum In the Symphony, the sound material shaped by the sound engineer is not fully a reflection of the way of thinking of the microformal composer. Therefore during the act of composition and creating of the Symphony, I came up with the idea to create its anti-thesis - music created entirely by the composer, put together from elements which give only him information about how he is shaping music by himself in all the registers.

Assemblage was recorded with a special editing technique from a couple dozen of only slightly deformed, violin and piano "emotiographs." The sound is therefore authentic: this is how the composer plays, feels and understands his music (this refers in particular to the rhythmic articulatory sphere and the so-called aesthetic of instrumental sound). But to give the whole a formal consistency, in the last phase of composing, the artist used a stereo without processing the material. In opposition to the Symphony, Assemblage remains an authentic instrumental composition. This is how, through natural sounds, composer's emotions were introduced into electroacoustic music.

Almost every piece that saw the light of day in the early years of the Experimental Studio of the Polish Radio marked a new chapter in the history of technology and aesthetics. New and divergent paths which would take shape years later in different songs were being laid down.

Author: Marek Zwyrzykowski, translator Mai Jones 04/07/2014

Marek Zwyrzykowski, photo: Wojciech Kusiński / Polskie RadioMarek Zwyrzykowski is a journalist and musicologist who graduated from the University of Warsaw in 1977. He has been cooperating with Musical Editorial Board of the Polish Radio since 1978. Since the 2004 merger of the Experimental Studio with Channel Two Polish Radio, he heads the production of electroacoustic music production.

He is the author of musical auditions and dozens of interviews (with Krzysztof Penderecki, Wojciech Kilar, Andrzej Wajda, Jan Krenz, Antoni Wit, James MacMillan). His radio work has a focus on electroacoustic music and since 1990 he has been broadcasting the programme Hortus musicus - hortus electronicus on Channel Two Polish Radio.

He has been awarded with the Hungarian Radio award for the radio show Béla Bartók - sketch for a portrait (1981) and the Polish Radio award for a radio series on Karol Szymanowski (1982). In 2013 he received the Polish Radio Golden Microphone.