Prefer listening to reading? Click the image below to listen to the Stories From The Eastern West podcast about Warsaw's infamous palace.

Stalin Had an Idea

Let’s dive deep into history. I was looking diligently, and for a long time, but I couldn’t find what I was searching for. Obviously, I found plenty of gifts; monarchs, princes and magnates had been exchanging precious presents since ancient times, but a gift given from the people of one nation to the people of another nation? This is simply unprecedented!

– Karol Małcużyński, Trybuna Ludu (People's Tribune), 23rd December, 1952.

This is how the official media outlet of the ruling Polish United Worker’s Party (PZPR) announced Joseph Stalin’s idea of building a skyscraper over 200 metres (650 feet) tall in the middle of Warsaw’s post-war ruins. How Stalin’s idea came into being is a story Warsaw will never forget...

One day, Józef Sigalin, architect-in-chief of Warsaw, received a classified telegram about the upcoming visit by Stalin’s aide, Viacheslav Molotov. The telegram confidentially informed Sigalin that the Soviet official was likely to come up with a ‘spontaneous’ offer of building a high-rise in Warsaw. There were also some instructions attached: don't go into details, take a positive position overall, and don't look confused. On the next day, during a visit, Viacheslav Molotov ‘spontaneously’ asked: “How would you like a high-rise building, just like one of ours, in Warsaw?” Sigalin answered, following his instructions: “Well, why not?” This is how it was decided to construct a 42-floor colossus in the middle of the city.

Leonard Sempoliński, 'The Palace of Culture and Science with ruins', 1956, photo: courtesy of the author's inheritors

Leonard Sempoliński, 'The Palace of Culture and Science with ruins', 1956, photo: courtesy of the author's inheritorsSoviet Design

Soon, Józef Sigalin, who also ran the Office for the Reconstruction of the Capital (Biuro Odbudowy Stolicy), was asked by the Prime Minister to work on plans and recommendations for the Soviet architects who were to carry out the whole process. The problem was that there was hardly any data about what the Soviets were planning to build. There were rumours that an exact copy of the University of Moscow was to be built, but the only model Polish architects were given were some photos of the aforementioned university from a two-year-old Soviet magazine. No scale, no technical data, no practical information. They quickly understood that their role in deciding the eventual shape of the ‘gift’ would be tangential. Indeed, when the Polish delegation of architects went to Moscow a few weeks later they found out that almost everything had already been decided:

- Obviously, the building was to be built in the Stalinist Gothic style

- Lev Rudnev, the architect of Moscow University, was to be its designer

- Construction was to be financed and carried out by the USSR.

- Materials from the USSR were to be used for the most part and Soviet builders would be hired

- The Polish government was to decide the exact spot in Warsaw where it was to be built as well as how the building was to be used

- Construction was set to start mid-1952 and was meant to last 2 and a half to 3 years

Jóżef Sigalin, presenting construction plans to president Bierut, photo: MHW

Jóżef Sigalin, presenting construction plans to president Bierut, photo: MHWIn the subsequent months, a wide delegation of Soviet officials came to Poland to gather the information they needed to start working on the actual project. They were invited to tour Poland and presented with typical Polish architecture so that the project could match with the overall Polish urban landscape. However, despite all these endeavours, the whole process of planning and constructing the palace was typically Soviet in the way it was carried out.

Architects decided that it would be set in the middle of a huge, 3.3 hectare (8.2 acres) square in the city centre. Even though Warsaw was at that time brutally devastated after World War II, this decision meant demolishing all the remnants of the pre-war 19th-century tenement houses, leaving them no chance for future reconstruction.

Preparatory works for the construction of the Palace, circa 1952, photo: Forum

Preparatory works for the construction of the Palace, circa 1952, photo: ForumIt was also Soviet in the way that ideology was mixed with technical and architectural aspects. The palace was given to Poles as a token of Soviet-Polish friendship and from the very beginning it was to be easily visible from every part of the city and to tower above all other Warsaw high-rises (the highest at that time was no more than 30% of the palace’s height). By the time it was decided how big it was going to be, there was still no precise idea about the intended use of it. Rarely does one build a high-rise without a practical purpose, and obviously there where many political and ideological purposes: showing off Soviet domination of this side of the Iron Curtain, the Soviet’s pretence of offering better help than the Marshall Plan, and finally a populist act of giving a palace to the people, an act clearly demonstrating the new order, where the working class is the one with privilege and respect.

Under Construction

There are two sides to every story, including that of the palace’s construction. The first is that construction was heavily disrupted by propaganda. Almost every step was finished earlier than planned, just to show how efficient Soviet workers were or to commemorate some Communist anniversary or festivity even as absurd as the Month of Massification of the Community for Soviet-Polish Friendship.

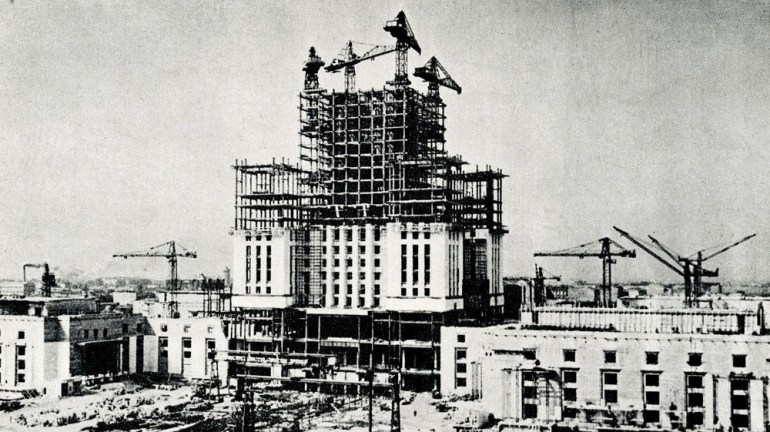

Constructoin fo the Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw, circa 1952, photo: FoKa/ Forum

Constructoin fo the Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw, circa 1952, photo: FoKa/ ForumWorkers and engineers, in addition to working several shifts in a row, were constantly filmed and interviewed, and they were obliged to participate in parades and meetings with scouts, students and other workers. The Polish Film Chronicle (fully subordinated to the Communist Party) filmed numerous episodes presenting the construction as a flawless process of perfect cooperation between Soviets and Poles, as a dreamt-of occasion for Poles to draw on the experience of Soviet engineers, and as the very last step to finally fend off the ‘imperialist threat’ – a propagandistic expression used for any kind of activity by Western civilization in Eastern Europe. In fact, the non-stop rush was one of the main factors that brought about the deaths of 16 Soviet workers and many more non-fatal accidents.

The other side is that the palace was built astonishingly quickly and still remains in very good condition today. Indeed, it was built mostly by 3,600 Soviet and some Polish workers supervised and trained by Soviet engineers. Moreover, some of the technical ideas used during the construction were truly innovative, and were used for many years during construction of other large-scale buildings in Poland.

Soviet workers on the Palace's construction site, Warsaw, circa 1952, photo: Forum

Soviet workers on the Palace's construction site, Warsaw, circa 1952, photo: ForumBecause the construction of the palace took place entirely during the Stalinist era, the period marked with the most severe terror and repression of the Communists’ political enemies, voices of moderate enthusiasm or dissatisfaction remained private and unspoken. Only visitors, like Gerard Philipe, a famous French actor, could be honest with their opinion on the palace. He said of it: 'It’s little but stylish.' Officially, Poles were delighted with the gift and couldn’t wait until its was finished.

20 floor-tall Palace of Culture and Science , 1952, Warsaw, photo: FoKa/ Forum

20 floor-tall Palace of Culture and Science , 1952, Warsaw, photo: FoKa/ ForumOn 21 July 1955, the ambassador of the Soviet Union and the Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of Poland signed the transfer deed and the construction of the Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science (Pałac Kultury i Nauki im. Józefa Stalina) was over. On the next day the Palace was opened for public.

50 Years of Controversy

The palace’s brutal mismatch with Warsaw’s architecture and its overwhelming dominance over the urban landscape of the recovering city made it the most controversial building in the history of Warsaw. Soon after Stalin’s death voices of criticism became audible. Some people perceived it as a sign of the Soviet occupation rather than the Soviet people’s generous gift. Others were convinced that resources used for its construction could have been better used for reconstruction of the razed Warsaw. Soon, the palace acquired ironic nicknames: Pekin (Polish for Beijing because the abbreviation of its full name in Polish is PKiN, but also a nickname for the biggest brothel in pre-war Warsaw) or Pajac (Polish for Clown, the words palace and clown sound almost the same in Polish).

Palace of Culture and Science by night, Warsaw, 2015, photo: Andrzej Bogacz / Forum

Palace of Culture and Science by night, Warsaw, 2015, photo: Andrzej Bogacz / ForumToday, the palace is no longer named after Joseph Stalin but ironically it has become one of the capital's most popular buildings and a symbol of the city. Despite the many groups that wanted to tear it down after the fall of Communism, despite several businessmen who wanted to buy it, despite Taiwanese architects who wanted to chop it into four parts and relocate them in other parts of Warsaw, the palace stands where it has always stood and is still visible from most parts of the city. It remains the tallest skyscraper in Poland.

It has become a multifunctional building. There is a multiplex cinema inside, a concert hall with a capacity of 3000, a university, two museums, four theatres, a few popular clubs and a huge swimming pool. The terrace on the 30th floor is one of the places most tourists visit during their stay in Warsaw.

Swimming pool inside the Palace of Culture and Science, photo: Mariusz Grzelak / Reporter / East News

Swimming pool inside the Palace of Culture and Science, photo: Mariusz Grzelak / Reporter / East NewsIn 2007, the Palace was put into the registry of objects of cultural heritage in Poland, thus was accepted by the Polish state as part of its cultural heritage. This decision, even if very controversial ideologically, only acknowledged what already was a fact – no matter what Varsovians think or wish, the Palace of Culture will remain here for years (ages?), reminding of Poland’s troubled history and remaining a one of a kind tourist attraction.

Author: Wojciech Oleksiak