He was the chronicler and designer of the Polish national identity. Ashes and Diamonds defined the way of thinking about the immediate post-war years, and in A Generation Wajda was the first to deal with the tragic fate of the generation of Columbuses – poets who were born right after World War I and entered adulthood at the outbreak of World War II, which tragically marked their youth. In Lotna he created one of the cruellest depictions of Polish Romanticism, Man of Marble squared accounts with the communist regime in Poland, and in Man of Iron Wajda set out to grasp the turmoil of the Solidarity movement as it unfolded.

Here is a selection of the most important historical films by Andrzej Wajda.

The Ashes (1965) – Napoleon and Polish myths

As Wajda said in an interview,

’I decided to make a film adaptation of the work of Żeromski and not Sienkewicz, because I am not interested in literature of national reconciliation, literature that is trying to reconcile everybody with everybody.

The Ashes, the last picture of the Polish Film School movement, did indeed spark a national discussion in which writers, historians and journalists debated the essence of patriotism.

As the director reminisced years later:

The healthy patriotism of Sienkiewicz was considered exemplary at the time. It didn't help to explain that the criticised scenes, situations and dialogues are taken from the novel by Żeromski and not Sienkewicz. Nobody intended to check that. Mieczysław Moczar [editor’s note: a highly prominent figure in the communist regime, Minister of the Interior between 1964 and 1968] and his people wanted to divide our society as quickly as possible, and the worst case scenario was to split the artistic elite into two groups: revisionists and true patriots. This is how I became a revisionist, and it hindered the making of my films.

World War II

Lotna (1959) – September 1939

The titular Lotna is an Arabian mare given to a Polish army rotmistrz [editor’s note: commissioned cavalry officer] by the administrator of a magnate’s stud. In the film, the horse becomes a symbol of the old world’s death. Numerous references to classics of Polish painting, especially Artur Grottger, allude to the Polish Romantic tradition.

Lotna became notable in the history of cinema thanks to a scene in which cavalry charges a unit of German tanks, an image in which Wajda gloomily portrayed the warped Polish understanding of heroism. The symbolic white horse would return both in Wajda’s later films (the steed falling into a precipice in The Ashes, or The Birch Wood) and in the works of other directors, such as Jerzy Skolimowski’s Essential Killing.

Katyń (2007) – 17th September 1939

Still from Andrzej Wajda's "Katyn", photo by Fabryka Obrazu / East News

Still from Andrzej Wajda's "Katyn", photo by Fabryka Obrazu / East NewsWajda didn’t direct many films as personal as Katyń.

It was a story about my mother. My mother was a victim of the lie about Katyń, and my father was a victim of the Katyń massacre. In the first film about it, it was hard not to show both of these perspectives - as Wajda told Tadeusz Lubelski in an interview for Kino magazine.

The story about prisoners of war, officers of the Polish army executed in the woods near Smoleńsk by the Soviet NKVD secret police agency, was told by the widows waiting for the return of their loved ones. Katyń closed the 'panorama of Polish fate', as the director himself put it, and in 2008 was shortlisted for the Oscar for best foreign language film.

Korczak (1990) – 1936-1942

In 1968 Aleksander Ford began working on a film about Janusz Korczak. However, the anti-Semitic campaign of March 1968 forced Ford to leave Poland, and his film fell through (it was only in 1974 that Ford made You are Free, Dr. Korczak in West Germany). Wajda witnessed these events, and considered the hasty dismantlement of the sets for the film as one of the most shameful events of his life.

Years later, Wajda decided to make his own picture about the life and death of Korczak. The screenplay was written by Agnieszka Holland, and Wojciech Pszoniak played the protagonist.

However, the film never gained international popularity, mostly due to the accusations of anti-Semitism and historic inaccuracy made by Danielle Heyman, a critic for Le Monde. Although these allegations were completely absurd to Wajda, the film is considered controversial.

The Warsaw Uprising

Canal (1956)

Wajda was the first film director to attempt to tell the story of the Warsaw Uprising. When he was shooting in 1956, the inhabitants of Warsaw gave the director hints – where exactly the insurrection’s fights took place, which drains were used to escape to the sewers… The audience expected a heroic story about noble patriots ready to sacrifice their lives for freedom.

Wajda told a story about the war stripping people of dignity, and about the tragedy of young people becoming victims of history. Even though the contemporary political head of national cinematography was sceptical about the project, in 1957 Canal was awarded at the Cannes Film Festival. As the director wrote years later:

The Special Jury Award protected my film from Polish critics and audiences. It was hard to be surprised at the latter group’s reaction – most of them were members of the uprising or families that lost their loved ones in Warsaw. This film couldn’t have satisfied them. They have already licked their wounds, mourned their loved ones, and now wanted to see their moral and spiritual victory, and not death in the sewers.

Ashes and Diamonds (1958) – May 1945

The most important picture in the history of Polish cinema and one of the works that defined the thinking about Polish post-war history, the film adaptation of Ashes and Diamonds made the novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski immortal. Wajda made its action more tense and rejected its political politeness as much possible. The senselessness of killing and uncertainty regarding what tomorrow brings, being faithful to an oath and hungry for hope, cooperation with the new authorities and the necessity of fighting for freedom – on the one day in which the story of Maciek Chełmicki unfolds, the Polish past meets the Polish future. The excellent cinematography by Jerzy Wójcik and the legendary acting of Zbigniew Cybulski and Adam Pawlikowski contributed to Wajda’s film becoming the most crucial work of the Polish Film School movement.

The Solidarity movement, disappointment with socialism

Man of Marble (1976) – 1952-1970

Before Wajda started shooting Man of Marble, he had spent 14 years convincing the policy-makers that his film wouldn't be a critique of the communist state. It is hard to tell how he did it. His film is one of the most painful depictions of the communist regime in the history of cinema. The authorities wanted to prevent the film from being presented at any foreign festival, but thanks to its French distributor the film was shown outside the competition at Cannes Film Festival, where it gained the appreciation of both the audience and the critics.

Man of Iron (1981) – 1968-1980

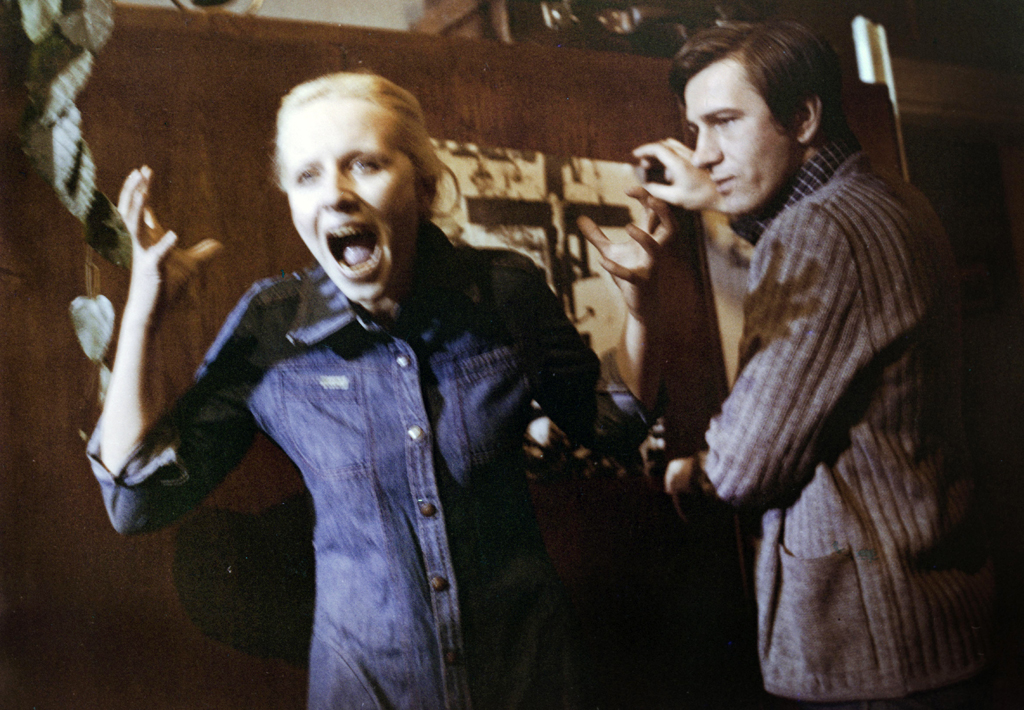

Still from the film Man of Iron picturing Krystyna Janda and Jerzy Radziwiłowicz, photo: National Film Archive / www.fototeka.fn.org.pl

Still from the film Man of Iron picturing Krystyna Janda and Jerzy Radziwiłowicz, photo: National Film Archive / www.fototeka.fn.org.plThe impulse that started the making of Man of Iron were the strikes in Gdańsk Shipyard. When Wajda visited the place during the turmoil, one of the workers said: ‘Please, make a film about us’. As the director reminisced years after, ‘I have never made a film to order, but this plea was simply impossible to ignore’. The screenplay by Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski was written in six days, and even though shooting began in January 1981 it was as soon as in June of the same year that it was presented to the striking workers. The film was awarded the Golden Palm at the Cannes Film Festival, which didn’t prevent the media of the regime in Poland and the Soviet Union from calling it a ‘piece of political propaganda seeking to strengthen the authority of the reactionary union’, as the Moscow-based Iskusstwo Kino wrote.

Danton (1982) – Paris 1790, that is Gdańsk 1980

This drama by Stanisława Przybyszewska gives an account of the 18th-century French Revolution. While getting ready to adapt it for cinema at the end of 1981, Wajda invited Gerard Depardieu to Warsaw to acquaint him with the people behind the Solidarity movement:

I wanted Depardieu to see the face of the revolution – incredibly tired, with wide open eyes that suddenly fall asleep and dream a dream that will never come true … There were no words or no director who would be able to make a better introduction to my new film, Danton, than what Gerard could see and experience personally.

The film that was considered inaccurate in France because of the way it depicted the relationship between Danton and Robespierre was interpreted in Poland as a commentary on the banning of the Solidarity trade union in December 1981.

Man of Hope (2013) – 1980-1989

Wajda commented on the last part of the trilogy, Man of Hope, in an interview for Kino monthly:

It is going to be a film about her – about the marble woman, the iron woman, the steel woman, to put it briefly – about a woman who is able to resolve the conflict of her situation: she’s able to both fulfil her home duties while supporting her husband who is participating in big politics, in the grand events that he’s facing.

Man of Hope is a story about politics storming into the life of an ordinary Polish family.

Sources: Wajda.pl, Filmpolski.pl, "Historia niebyła kina PRL" Tadeusz Lubelski, Kraków 2012; "Wajda", Tadeusz Lubelski, Wrocław 2006; "Kino i reszta świata" Andrzej Wajda, Kraków 2000; "Wajda mówi o sobie : wywiady i teksty" Andrzej Wajda, Kraków 2000; "Wajda. Przewodnik Krytyki Politycznej", Warszawa 2012. ed.: Bartosz Staszczyszyn September 2013