John Paul II

Pope John Paul II can boldly be called the number one Polish saint. The vast majority of Poles adore him and are proud of him. In many Polish households, you can find his photographs, books and even CDs. Yes, CDs. As it turns out the Pope loved to sing and released two albums. This extraordinary man, who was made a saint by the Catholic Church in 2014, was more than just a philosopher, theologian and spiritual leader. Born Karol Wojtyła in Wadowice, Poland, as a young man the Pope wrote poetry, acted in theatre, spoke a whopping nine languages fluently and loved to swim and hike. This is far from a full list of his interests and hobbies.

John Paul II was also an unbelievably generous man, able to forgive even the most terrible sins. On 13th May 1981 a member of a far-right Turkish faction ‘Grey Wolves’ Mehmet Ali Agca attempted to assassinate him. The Turk shot the Pontiff in the stomach and was detained immediately afterwards. Two years later Karol Wojtyła visited the man in jail. ‘I spoke to him as a brother, whom I have pardoned. He deserves my complete trust.’ – the Polish pope said afterwards and asked the court to pardon him. In 2008, the man who attacked the pope converted to Catholicism. The story of Ali Agca was told by reporter Witold Szabłowski in his collection of essays on Turkey, The Assassin from Apricot City.

In Poland, the cult of the Polish pope is unusually strong. In practically every big city there is a street, square or alley named after him. Tourist companies lead tours ‘in the footsteps of John Paul II’. Those who believe that Poles only adore the pope simply because he is their fellow countryman are mistaken. Pope John Paul II played a key role in the fight against the communist regime. On 2nd June 1979, during his first pilgrimage to Poland as pope, John Paul II celebrated mass in Pilsudski Square in the centre of Warsaw. During the mass, he spoke the words that millions of Poles took as support and a call to action: ‘Let your Spirit descend and renew the face of the earth. Of this land!’. A year later, the Solidarity movement was born and went on to liberate Poland from under communist oppression. Karol Wojtyła’s words were one of the first slogans of the legendary organisation.

Pope John Paul II was proclaimed a saint of the Catholic Church on April 27, 2014.

Maximilian Kolbe

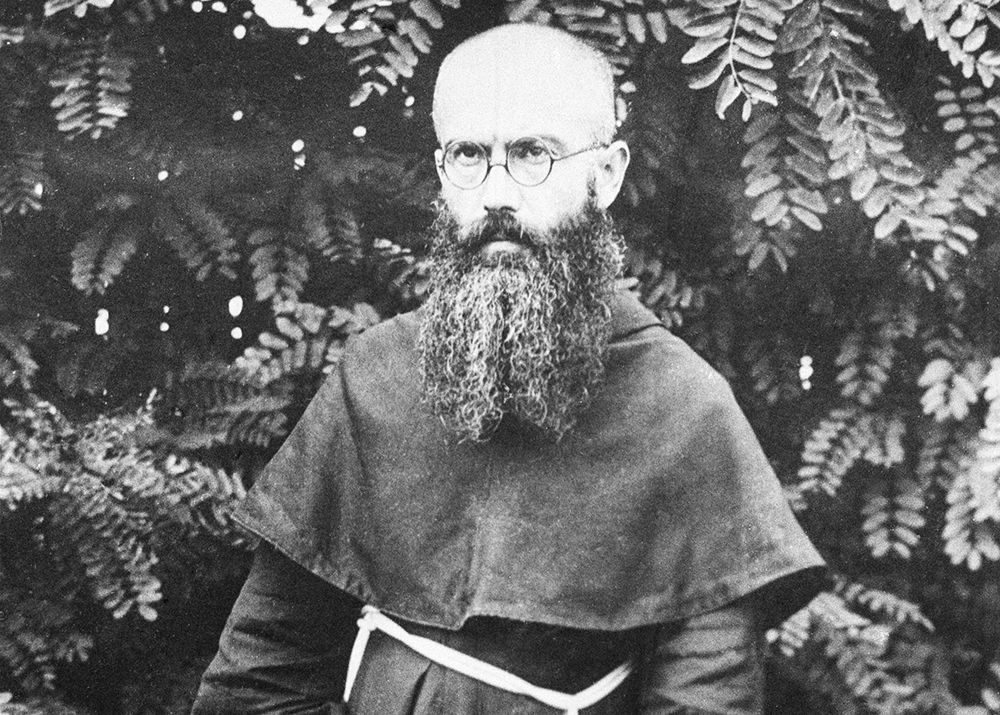

Maximilian Kolbe, photo: Laski Diffusion / East News

Maximilian Kolbe, photo: Laski Diffusion / East NewsFebruary 1941. The Gestapo arrested the Catholic Franciscan priest Maximilian Kolbe. At first, the Third Reich police officers placed him in the Pawiak prison, and then transferred him to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. The priest, who was once fond of mathematics, physics and even filed a patent for an apparatus that enabled space flight in 1915, never returned from Auschwitz. In June, the guards learned that some of the prisoners had successfully escaped. The camp commander Karl Fritzsch immediately sent a search team after the fugitives and all of the remaining prisoners, including Maximilian Kolbe, were brought into the courtyard of the barracks. They were not fed. The food that the prisoners were expecting was demonstratively thrown in a ditch. The next day, the guards forced the prisoners to stand under the scorching sun, beat them and continued to starve them. Because the search for the fugitives was unsuccessful, Fritzsch, who was famous for his cruelty, decided to put ten prisoners in a bunker to starve to death. One of those chosen was a sergeant of an infantry regiment named Franciszek Gajowniczek. ‘I’ll really never see my wife and children again? What will happen to them?’ – the man burst into tears. Maximilian Kolbe stepped forward. The priest offered his life in place of Franciszek’s. Fritzsch accepted the trade.

After two weeks, the Nazis decided to clear the bunker where the prisoners were left to die. They killed Kolbe and three other men who were still alive by administering carbolic acid injections. The jailer Bruno Bargovek later recalled:

When I opened the green door, Kolbe was already dead, but it seemed to me that he was alive. He was still sitting leaning against the wall. His face was lit up with an unusual light. His eyes were wide open and fixed on one point. It was like he was enveloped in joy. I will never forget him.

In 1982, the Catholic Church canonised Maximilian Kolbe. The honorary guest of the solemn ceremony was Franciszek Gajowniczek, the man the priest gave his life for. The sergeant, who Kolbe saved, lived a long life and passed away at the age of 93.

In the Catholic Church, Saint Maximilian is considered the patron saint of political prisoners, journalists, and prisoners.

Saint Wojciech

Saint Wojciech, patron saint of Poland. Replica of the painting: Dagmara Smolna

Saint Wojciech, patron saint of Poland. Replica of the painting: Dagmara SmolnaSaint Wojciech is not only one of the most well-known saints in Poland, but he is also revered in other countries. He was born in 955 in the Czech Republic, was bishop of Prague and visited Hungary and Poland. By origin Wojciech (in the church he is also called Saint Vojtech or Adalbert) belonged to a noble Czech family known as the Slavinks. He was gravely ill in his childhood. His parents, fearing for the life of their child, vowed to God that if their son recovered they would do everything so that he would become a priest. At 15 they sent the youth to study in a monastery. It was a perfect fit for Wojciech: he loved to teach, help people and was well educated. He found his place in the church.

Some of our readers may remember how on the eve of the year 2000 many predicted the end of the world. The situation was no different on the eve of the year 1000. Bands of charlatans who offered salvation and healing in exchange for money cropped up in various countries. Wojciech wanted to crack down on this practice. Not far from the Christian country of Poland sat pagan Prussia, and in 997, Wojciech decided to travel there to tell the local inhabitants about Christ and warn them about idolatry. He arrived in a ship given to him by the Polish king Bolesław Chrobry I. The locals met the stranger hostilely. If Wojciech’s biography by Benedictine monk Canaparius is to be believed, the priest was attacked by a pagan priest whose brother was killed at the hands of the Poles. The Prussians brutally murdered Wojciech.

There are several legends about what happened after the death of the martyr. It is well known that King Bolesław commanded his subordinates to buy back Wojciech’s ashes. According to one version, they paid the same weight in silver as the missionary’s body; to another – the same weight in gold as his head; to a third – they did not have to pay at all, because the ashes became weightless and the frightened Prussians gave them away as a gift. Then the Czech bishop allegedly decided to take the relics back from the Poles. After opening the lid of the sarcophagus everyone was overcome by a blissful state. What happened later is the stuff of legends. What we do know is that Wojciech is one of the most revered saints and one of the three main patron saints of Poland.

Faustyna Kowalska

Faustyna Kowalska, photo: SBM archive

Faustyna Kowalska, photo: SBM archiveThe next time you stop by any church, take a careful look at the walls. An unusual icon of Jesus inscribed with the words ‘Jesus, I trust in you‘ hangs in many Catholic churches around the globe. On the canvas, Christ is in white clothing, pointing with his left hand at his heart, from which two beams emanate – white and red. This image of Jesus was seen repeatedly in visions by Polish nun Faustyna Kowalska, who lived at the beginning of the last century. According to Sister Faustyna, during the visions God would speak with her, instruct her, encourage her and even dictate prayers. It is worth noting that the church always treat priests, monks or simply believers, who talk about supernatural experiences such as meetings with God with great caution. The experience of the Polish nun was no exception: Kowalska’s mentors were afraid that she had simply lost her mind. In 1933, Sister Faustyna was sent to a psychiatrist, yet the doctor, Helena Maciejewska, concluded that the woman was in perfect mental health.

Faustyna recorded her experiences, thoughts and everyday occurrences. Kowalska’s Diary is a masterpiece of mysticism, published in many of the world’s languages. It is worth reading how beautifully Sister Faustyna writes about her feelings: ‘I found my purpose at the moment when my spirit is submerged in You, the single object of my love. Everything else is nothing in comparison to You. Suffering, obstacles, humiliation, failure, suspicions, whatever stands in my way – these are splinters that only serve to inflame my love.’

Albert Chmielowski

Albert Chmielowski, photo: Museum of Independence collection / East News

Albert Chmielowski, photo: Museum of Independence collection / East NewsAlbert Chmielowski was born to a rich aristocratic family in 1845 in the Russian partition of Poland. The family wanted their son to receive a good education, they hoped he would become engaged in the agricultural industry and would eventually maintain the family estate. These plans, however, were completely changed by the January Uprising of 1863-1864. The seventeen-year-old Chmielowski, like many other Poles, was dissatisfied with the rule of Russia over the Polish lands. He joined the rebels, was wounded and lost a leg. Fearing persecution, the young man moved to Paris and decided that he wanted to be an artist. He painted, received his education in Munich and Warsaw and became friends with other artists such as Aleksander Gierymski and the father of Witkacy, Stanisław Witkiewicz.

Albert Chmielowski left behind about one hundred works: watercolours, drawings and oil paintings. The artist painted, women, children and sunsets, but it was a sacred theme that changed his life. While working on Ecce Homo, which depicts Jesus in a crown of thorns shortly before his crucifixion, the artist decided to serve God. At the age of 35 he entered a monastery and began to help alcoholics, the poor and the homeless. The man from a wealthy family left his bohemian lifestyle and began creating shelters for those without a roof over their heads in Kraków, Lviv and Zakopane.

The amazing story of Albert Chmielowski so moved the young Karol Wojtyła that in 1949 he wrote a play about the artist-monk and in 1989, as Pope John Paul II, he made Albert Chmielowski a saint. Eight years later, famous Polish director Krzysztof Zanussi made the film Our God’s Brother, based on the eponymous work of Karol Wojtyła.

Saint Jadwiga

Portrait of Saint Hedwig, photo: National Museum of Poland

Portrait of Saint Hedwig, photo: National Museum of PolandSome call Saint Jadwiga ’Queen,’ as she was the queen of Poland from 1834. The manners, traditions and limits of acceptability then were very different from what is considered acceptable now. Jadwiga became the queen of Poland at age 11. When she was 12, she married the Lithuanian prince Jagiełło. Her life was very short – she died in childbirth at age 25. Over the years of her reign the girl became famous for her kindness and generosity. Jadwiga knew four languages: Polish, Hungarian, French and Latin. She was well-versed in music and the fine arts. She became the first monarch of Poland to order a translation of parts of the Bible into the Polish language. Jadwiga donated money to the construction of churches, hospitals and dormitories for students. The Catholic Church canonised her in 1997, yet the cult of Jadwiga began in the 15th century, immediately after her death: people worshiped her, as a sign of gratitude to the saint they brought chains, rings and other jewellery to churches and hung them on the walls and created icons with her image. Saint Jadwiga is known as the patron saint of Poland.

Jerzy Popiełuszko

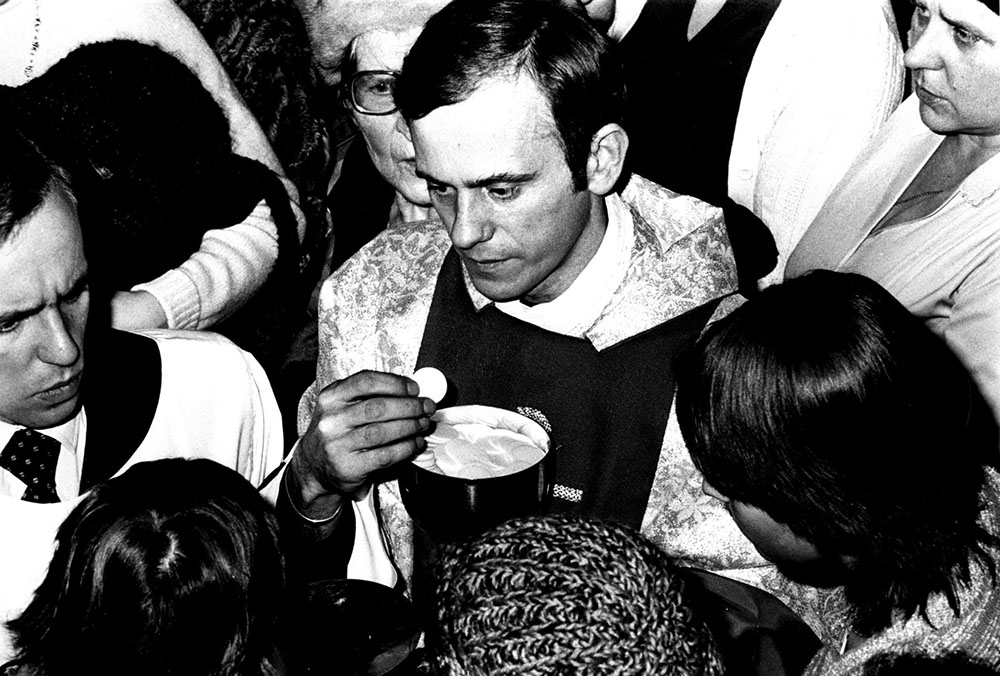

Jerzy Popiełuszko, photo: Erazm Ciołek / Forum

Jerzy Popiełuszko, photo: Erazm Ciołek / ForumWhen writing about Polish saints, one cannot leave out priest Jerzy Popiełuszko. Though officially the Catholic Church has not canonised him yet, in the minds of many Poles he is already a saint. Father Jerzy was an opponent of the communist regime: his sermons were broadcast on Radio Free Europe. Intelligence agents, of course, never took their eyes off him. At first, they tried to make the priest a secret agent – this is evidenced by documents of the security services of the communist regime in Poland, which became accessible after Poland regained its independence. When the priest refused to cooperate, the security services had him followed. Interestingly, some of these tails were also priests. Interrogations, charges of anti-government activities, provocations – the life of Father Jerzy was replete with such events after he became the chaplain of the Solidarity movement. He was accused of ‘abusing the themes of freedom and conscience’ in his sermons. During searches, security agents planted grenades, bullets and explosives on Popiełuszko and then claimed they ‘found’ them in his possession. The security agents would be accompanied by journalists, or more accurately propagandists, who wrote about the incidents, making Popiełuszko out to be a terrible threat to the communist regime. The mainstream media called Father Jerzy’s masses ‘sessions of hatred’. Despite this, thousands of Poles supported the priest and listened to his speeches.

Popiełuszko’s story ends in tragedy. On 19th October 1984, employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the People’s Republic of Poland detained the priest when he was returning to Warsaw. He was beaten, thrown into the trunk of a car and brutally murdered. This was an order from the top: the authorities understood that the only thing that could stop this person was death.

Crowds of outraged Poles came to the funeral of Solidarity’s chaplain. The farewell was more like a demonstration than a burial. The grave of the moral and spiritual leader of the Poles, Jerzy Popiełuszko, is located in Warsaw, in the courtyard of the Church of St. Stanisław Kostka.

Saint Stanisław

Saint Stanisław of Kraków on the painting from XVI, photo: wikipedia/lic. GNU

Saint Stanisław of Kraków on the painting from XVI, photo: wikipedia/lic. GNUThere are several Saint Stanisławs that are particularly venerated in Poland: a Kraków bishop who lived in the 11th century, a Polish Jesuit who died from malaria at age 18 and Stanisław Papczyński, the founder of the first Polish religious order for men, the Marian Fathers. From a historical point of view, the first of these deserves special attention. Stanisław Szczepanowski was a descendent of a noble family and bishop of Kraków (Kraków was the capital of Poland at that time). In those days, the church depended on the state so strongly that only the highest authorities could appoint a person to such a lofty post in the church hierarchy. The decision that Stanisław would be bishop, most likely came from the king of Poland himself, Bolesław II the Bold. Much indicates that the bishop was a reckless person. He was not afraid of his patron-monarch and would openly argue with him. The conflicts led to the king first to order Stanisław’s ear, nose and fingers to be cut off, yet his subordinates refused to carry out the order. Therefore, the king killed the bishop himself with a sword – Gallus Anonymus recorded these events in his chronicles. What brought about this violence? Many different versions of the story exist. According to one of them – Stanisław was a traitor; to another - the bishop paid the price for standing up for women who cheated on their husbands; to a third – the king deprived the priest of his life for excessively criticising him in his sermons. This is far from the entire list of hypotheses. Stanisław was canonised in 1253. The story of the saint inspired the creator of the Polish school of historical painting Jan Matejko to paint the picture ‘The Slaying of St. Stanisław’.

Originally written in Russian, 12 Apr 2017; translated by KA, 16 May 2017