The year 2017 will mark the 20th anniversary of Bester’s adventure with Klezmer music – playing concerts in Kraków and around the world. In 2000, his band, the Cracow Klezmer Band, published their first album for the Tzadik record label based in New York and run by John Zorn, an avant-garde and jazz music legend. Bester’s band is the only Polish band which has continuously worked with the most important Jewish music record label. They have released 8 albums under the label. Jarosław Bester says:

I asked myself: How would Klezmer sound, if there had been no Holocaust? Jewish music would live on, but in what form? I wanted to create something modeled on the tango nuevo by Astor Piazzolla, something new, but at the same time connecting the past and the present.

Filip Lech: We meet right after the opening of an exhibition about Jewish phonography. What was your first encounter with Jewish music?

Jarosław Bester: I was lucky, because in the mid-1990s I managed to find, with the help of my friends, pre-war recordings of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras, legendary clarinet players. I came into contact with really genuine Jewish music. I say really genuine because it was not disturbed or altered by the war. It didn’t carry those emotions.

Were there any famous Klezmer accordionists? I must admit that I don’t know of any...

Me neither, but that’s probably because the accordion is a very young instrument. In pre-war recordings, one can hear the dulcimer, which is a harmonic instrument just like the accordion. I’ve heard a few recordings with an accordion, but they are very rare. Anyway, these were old recordings, the descriptions only mentioned the names of the stars, not the other musicians.

What about contemporary accordionists?

It’s hard to be impartial when talking about musicians playing on the same instrument that I’ve played since I was a child. I’ve always associated accordions in Poland with cheap wedding instruments, a squeaky Weltmeister. They called it an Ikarus or a kaloryfer (Polish for ‘radiator’ – editor’s note). It was usually played by a pianist, who didn’t even know the proper technique. It’s not just there to pump air, as many think.

Nowadays much has changed, there are many new accordion pieces: from avant-garde to folk and jazz. It’s much more prevalent and accepted.

Jarosław Bester, photo: courtesy of the musician

Jarosław Bester, photo: courtesy of the musicianHow did you begin to learn about Jewish culture?

It was a number of things at once. In Kraków, at the beginning of the 1990s, there was the Jewish Culture Festival, and there was a slow revival of Kazimierz (Jewish district of Kraków – editor’s note), in the sense that new restaurants or exhibitions were opening, that were supposed to bring to mind pre-war Jewish life. There were no actual Jews there at the time – it was sort of folksy. But, at that time, just after the fall of communism, it was giving way to something new and interesting. It stimulated the imaginations of many artists, including my own.

Kazimierz used to be a place, where one could easily be attacked with a brick in a dark alley. But then, all of a sudden, you could walk into the district, see all of the formerly Jewish townhouses (although still, it was better to sightsee during the day). And then there was the Jewish Culture Festival – I remember going to my first cantor concert at the Tempel synagogue. I had never heard cantors singing live before, it was incredibly inspiriting. There were American musicians and Poles attempting their first tries at interpreting Jewish music (it wasn’t Klezmer yet, but rather sung poetry).

Step by step, I got more acquainted with a world that had previously been completely unknown to me – until 1996 I was only working with classical music: from accordion transcriptions of Bach to contemporary music, generally pieces which were pretty hard to swallow for an average listener.

You have won many prizes, the first one as early as 1987, at age 11.

Yes, it was during the Festival of Russian and Soviet Music (editor’s translation), I won second prize. This kind of event was common at the time, especially in the region I am from. I used to live in Nowa Huta, I attended the Mieczysław Karłowicz Music School, which was directly subject to the Lenin Ironworks in Nowa Huta. My performance was rather spectacular, the festival wasn’t divided into any categories: elementary school students, high school students and choirs all competed in the same contest. Fate wanted me to win second place. I played one of the children’s suites by Vladimir Merkushin and a transcription of the Flight of the Bumblebee by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

How did the Cracow Klezmer Band come to be?

By accident, like everything does. I was already interested in Klezmer music at the time, when the owner of the Ariel restaurant (now known as Klezmer Hois) where ‘so-called’ Klezmer music was played, asked me if I would be interested in starting a band. He already had a lead singer in mind – the band was only supposed to accompany her. We started playing pieces of Jewish poetry, not very well for that matter. The singer wasn’t really any good, but she fit in well with the ambiance of the pub. I always had great ambitions, sometimes too great, I assumed I had to be doing something extraordinary – I didn’t want to form yet another boring band. We ended up only working with the singer for a few months.

Around the same time, I won one of the most important accordion competitions held in Wrocław (the Polish Accordion Competition). I won first prize for the best concert performance with an orchestra and received prize money. I paid for our first demo recording with that money – an album which I called An Evening in Kazimierz (editor’s translation), with traditional instrumental Klezmer pieces. The cassette was never actually published, it was only distributed during our concerts in Kazimierz.

Later, we started to working with Beata Czarnecka, a singer from the famous Piwnica pod Baranami. Our programme, Zol Zayn – it was also sung poetry, but well done, and with entirely new orchestration, which I wrote. It really opened my mind, I realised that new arrangements wouldn’t lead us anywhere and that I wanted to write something new.

You’re originally from Kraków, a city which was once teeming with Jewish life. Don't you have any earlier memories of Jewish culture?

In Nowa Huta there were no Jews, people didn’t even have a notion of Jewish culture. We didn’t know who Jews were then, who they are today. Some thought a Jew was someone cunning, someone, who stole. But those were only isolated incidents. To be honest, I don’t remember any positive or negative opinions about Jews from my childhood.

But even then, many years later, when we were starting my band, Jewish music was still very much isolated. When I was still at the Music Academy, a handful of students would sing Hava Nagila when I passed.

Jewish music was around for many generations. Didn’t you want to explore places, where some of that culture somehow survived, for example, Zakarpacie?

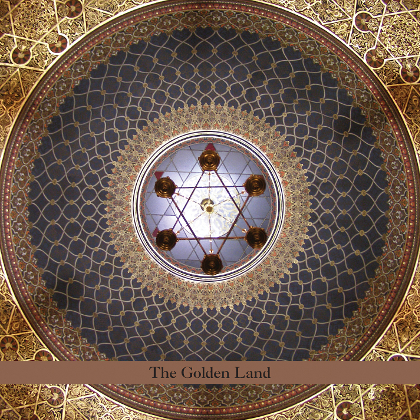

In 2004, while in Los Angeles, I was given an old collection of songs by Mordechaj Gebirtig, originally published in 1935. It was an interesting experience for me because I learned about the legendary Kraków-born poet while in the United States. I knew he was an important figure in the world of music and poetry, but nothing more. It’s a valuable relic for me, I used it when working on The Golden Land album (Tzadik, 2013), which features instrumental renditions of Gebirtig’s works.

At some point, my band started to drift away from Klezmer music, it actually happened quite rapidly. Our first album De Profundis (Tzadik, 2000) still has the Klezmer ‘vibe’, however, the following ones show us from completely different angles. I’ll explain why: when playing Klezmer music, I felt like a poorly polished rock, a reproducer, who is blindly exploring tradition – because honestly, who could teach me? Who could tell me all about it? I had to learn through trial and error.

I asked myself: How would Klezmer sound if there had been no Holocaust? Jewish music would be live on, but in what form? I wanted to create something modelled on the tango nuevo by Astor Piazzolla, something new, but at the same time connecting the past and the present.

Before recording your album at Tzadik, were you familiar with their music?

Back then John Zorn was already a legend in Poland, but we never actually heard his music. I was more interested in traditional, 'Klezmatic' sound. I had no idea that my music in a way overlapped with Zorn’s productions.

What did the production of your first album at Tzadik look like? It was the year 2000, how did you produce albums in the States back then?

We did all of the recordings in Poland, but the songs were mastered in the States. It was a big deal, to release an album there, especially for a band, that was known only by a few in Poland (before the release, we won first prize at the New Tradition Festival – Polish Radio’s folk festival). I can’t say that the Polish music world was electrified by it. Some reviewers took it upon themselves to publicise our achievement, others were silent, thinking of it as pure coincidence... The end of the 1990s and the turn of the 21st century in Poland was the time of the biggest interest in Zorn, and for many, it came as a shock.

Did you have a chance to actually spend time with John Zorn? What was your relationship like?

We got along very well. I know that he can be very rough on reporters, but he is friendly with musicians. He gave me a complete collection of scores from his cycle Masada. Book of Angels, packed in a beautiful gold box. I am one of the few artists, who received his hand-written compositions.

For me, Zorn is the father of contemporary Jewish avant-garde. He has created a family of musicians from around the world: both Jewish and not, who compose music on a similar level. After concerts, we would meet in a restaurant and would always sit at the same table. Joey Baron, Dave Douglas, John Zorn and other legends didn’t sit separately. He really valued the family atmosphere, there were no divisions.

Zorn is practically a father to you – did you find any other ‘musician-teachers’?

It all started in Kraków, the Jewish Culture Festival took us under their wing. Every year we presented our new material at the Festival. We met other musicians there that had worked with Zorn, for example, Frank London. Later, in Paris, we had the opportunity to play with Don Byron, a great clarinet player (we later recorded a piece together).

For a few years, we travelled to the States often, sometimes even 3-4 times a year. We would be in constant contact with musicians from Zorn’s circle. We would go to the iconic Tonic club (in business from 1988 to 2007 in Lower East Side –editor’s annotation), which held improvised concerts and participated in the spontaneous music making. We gradually bonded with that world. The culmination was the Masada Marathon, organised by Zorn in Milan, where we were the only band from Europe.

Zorn’s musicians stand out because they listen. Not only make music - and that’s crucial. For a humble accordionist from Poland, it was a big deal to play as equals with multiple album musicians. It was scary and stressful but was wonderful experience – to feel an energy which I hadn’t previously known.