You can also hear about Rotblat's struggle against the very thing he helped create on our podcast Stories From The Eastern West:

The bombs are dropped

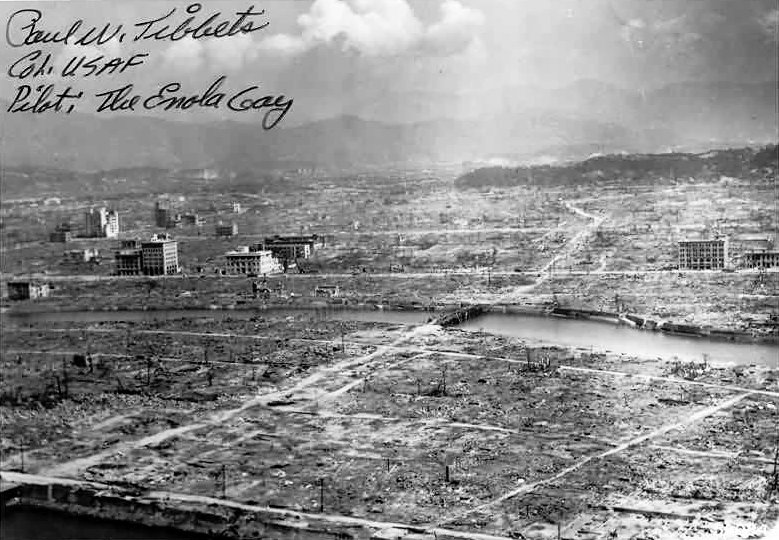

In early August, 1945, two Japanese cities were reduced to smouldering piles of rubble in a matter of minutes. Thousands of people lay dead among the ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and many more would die in the days to come from radiation. Both cities were nearly erased from the map.

The United States, after years of research and development, had succeeded in harnessing and weaponising the terrifying forces of nature. Scientists working in Los Alamos, New Mexico, had developed a revolutionary form of weaponry, one that had just been proven to be capable of destroying entire cities and civilisations.

Photo of Hiroshima after it was bombed, autographed by Enola Gay bomber pilot Paul Tibbets, photo: Wikipedia

Photo of Hiroshima after it was bombed, autographed by Enola Gay bomber pilot Paul Tibbets, photo: WikipediaThe so-called atomic bomb quickly brought about Japan’s surrender and the official end of the Second World War. The weapons used in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unequivocally the most powerful ever used, let alone created, in human history.

When the terrifying images of the ruined Japanese cities became publicly available, many were horrified by what they saw. How could mankind be capable of creating such destruction? Of wiping entire civilisations off the face of the earth?

A call to action

Hiroshima patients - burns due to atomic radiation of legs, photo: Wikipedia

Hiroshima patients - burns due to atomic radiation of legs, photo: WikipediaAmong those disturbed by what they saw was the Polish-born physicist Józef Rotblat. At first glance, Rotblat’s opposition to the bombs seems rather unlikely. He had actually worked on the Manhattan Project, the US-led undertaking to develop nuclear weapons, and contributed greatly to its development.

From a young age, Rotblat had believed science was a powerful tool that could serve humanity and save lives. He felt that this small group of scientists, and the government they were working for, had exploited science and betrayed the interests of mankind.

When the bombs were dropped on Japan, he was appalled by what he saw. He had lived through both world wars, but he had never seen destruction on this scale. When he first heard of the devastation, he was both heartbroken and terrified. Not only had these weapons killed hundreds of thousands of people, they had also, for the first time in history, created the possibility of nuclear war.

This was a terrifying prospect for Rotblat, but one he believed could be avoided.

So long as there is a risk of nuclear war, that risk is finite, and so long as that risk is finite, it can be reduced.

Shortly after the bombs were used, he decided to dedicate the rest of his life to anti-nuclear activism. He wanted to ensure these destructive weapons were never used again.

A life shaped by war

Józef (often referred to as Joseph) Rotblat was born into a Polish-Jewish family in 1908 in Warsaw, Poland. In his early years, his father owned several small and successful businesses, so his family was relatively prosperous. But the outbreak of the First World War completely reversed his family’s fortunes. His father’s businesses collapsed and they were rendered penniless.

The poverty he personally experienced and the cruelty he witnessed demonstrated to him the inherent senselessness of war.

I had a terrible experience, complete privation during the First World War. Hunger and cold and disease and witnessing death and so on. Cruel things were happening. At that time, I decided that I did not want to see any war once again.

Because of the penury in which they found themselves during the war, Rotblat’s parents could not afford to send him to a high school to receive formal education. Despite this, the passion he had developed for physics led him to take, and subsequently pass, the entrance exam for the Free University of Poland.

James Chadwick, photo: Wikipedia

James Chadwick, photo: WikipediaAfter earning his Master’s Degree from this university, he obtained his PhD in physics from the University of Warsaw. He travelled to France and the UK shortly after to study under the supervision of James Chadwick, who had won the Nobel Prize in 1935 for discovering the neutron. Soon after he began his studies with Chadwick, the Second World War broke out.

In the decades between the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland, the technological advancements made by the world’s military powers meant that the consequences of a renewed global conflict would be devastating. Nazi Germany’s Blitzkrieg warfare, and the ease with which they invaded Poland, was characteristic of this depressing trend.

For Józef Rotblat, the horrors of the war were all too real. When he first left Poland for England, he was unable to bring his wife due to a lack of money.

When he had earned enough, Rotblat travelled back to Poland to finally take his wife to England. But when he arrived, he found out she was too ill to travel. Once again, he was forced to leave her behind.

Just a few days after leaving, Germany invaded Poland. Unable to defend herself, she, along with so many others, perished in the Holocaust. Her death deeply scarred Rotblat.

We will never truly know whether the death of his wife served as an impetus for his activism, since Rotblat always refused to discuss this difficult period in his life. But it would be hard to argue that this tragic event did nothing to dramatically shape his worldview and inspire his pursuit of peace.

A lone conscientious objector

Manhattan Project meeting at Berkeley: Ernest O. Lawrence, Arthur H. Compton, Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Karl T. Compton, and Alfred L. Loomis, photo: Wikipedia

Manhattan Project meeting at Berkeley: Ernest O. Lawrence, Arthur H. Compton, Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Karl T. Compton, and Alfred L. Loomis, photo: WikipediaIn 1944, as the end of the war approached, Rotblat, through his connection with James Chadwick, joined the US-sponsored Manhattan Project. The project itself was initiated in 1942 in response to fears that Germany would attempt to build and use nuclear weapons.

Even though his wife had been killed by the Nazis, Rotblat always had reservations about the project and was far from enthusiastic. He was deeply fearful of the devastation that could result from the weapon they were developing.

So, I had to work out some rationale, and I gradually worked out this rationale of deterrence. But even then, I was not convinced that I should really work. So, this was a tumour which had been growing. Difficult to imagine this sort of torture, the mental torture of myself whether I should do something about it or not.

When it became apparent that Germany had abandoned its nuclear weapons programme, Rotblat, seeing little point in continuing, requested to be dismissed from the project. For him, the primary purpose of this project was to counter German nuclear developments – seeing that the Germans could no longer obtain such weapons, he believed continuing their work was senseless.

More importantly, when he finally realised the destructive capacity of the weapon he was designing, he decided he no longer wanted to be a part of something he believed to be completely unethical.

It became clearer gradually that the Germans are not going to make the bomb. The only reason really why I worked on the bomb was because of the fear of the Germans. This is the only reason. I would never have worked otherwise on this… My motivation for work on the bomb was becoming invalid.

Many officials at the project became suspicious of Rotblat when he announced his sudden departure. Some feared that he was secretly a Soviet-sympathiser and that he would disclose classified information about the Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union. This baseless paranoia continued for some time before he was finally allowed to leave the project and return to England.

In the end, he was the only scientist that abandoned the Manhattan Project before its completion. In a sense, he was the project’s only conscientious objector.

Shortly after his departure from the project, the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Rotblat’s worst fears had become a disturbing reality.

No more Dr. Strangeloves

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), photo: promo materials

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), photo: promo materials This is now a new world: a world full of danger. Shall we survive, now, with these new weapons now that they have been used? And so, I began to think, ‘How can we prevent a possible nuclear war?’

Rotblat believed that scientists of all disciplines have a moral obligation to consider the ethical ramifications of their experiments and research. Many of the atrocities committed in both world wars, specifically the detonation of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were, according to Rotblat, made possible because scientists failed to consider the repercussions of their research.

Furthermore, he believed that the continually-escalating arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union was perpetuated by those same scientists.

The disgraceful role played by a few scientists, caricatured as Dr. Strangeloves, in fuelling the arms race… they did great damage to the image of science.

The person to which he was referring, Dr. Strangelove, was the maniacal titular character in Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. An amalgamation of actual scientists, the caricature character demonstrated the devastating consequences of scientific irresponsibility.

Exposing the dangers of nuclear tests

Józef Rotblat receiving the Nobel Prize, 10/12/1995, photo: PAP

Józef Rotblat receiving the Nobel Prize, 10/12/1995, photo: PAPRotblat himself admired the part of the scientific community that possessed an unwavering dedication to saving rather than destroying life. He therefore began conducting research in the field of medical physics at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, where he remained for the entirety of his career.

During the 1950s, several countries began conducting above-ground nuclear tests at various locations throughout the world. While working at St. Bart’s, he became particularly interested in researching, and potentially exposing, the disastrous effects of nuclear fallout that came from these tests.

After investigating Castle Bravo, the largest nuclear test ever conducted by the United States, he found that the amount of contamination initially believed to be released was being severely underestimated. When his findings were published, it was also discovered that many people all over the world were unknowingly exposed to the deleterious effects of nuclear fallout.

His research on its effects was both ground-breaking and distressing. The findings he published sparked a public debate on the safety of these tests, which eventually culminated in the signing of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963. The treaty banned all nuclear tests conducted above-ground and underwater, playing a vital role in reducing the concentration of radioactive material in our atmosphere.

The Pugwash Conferences

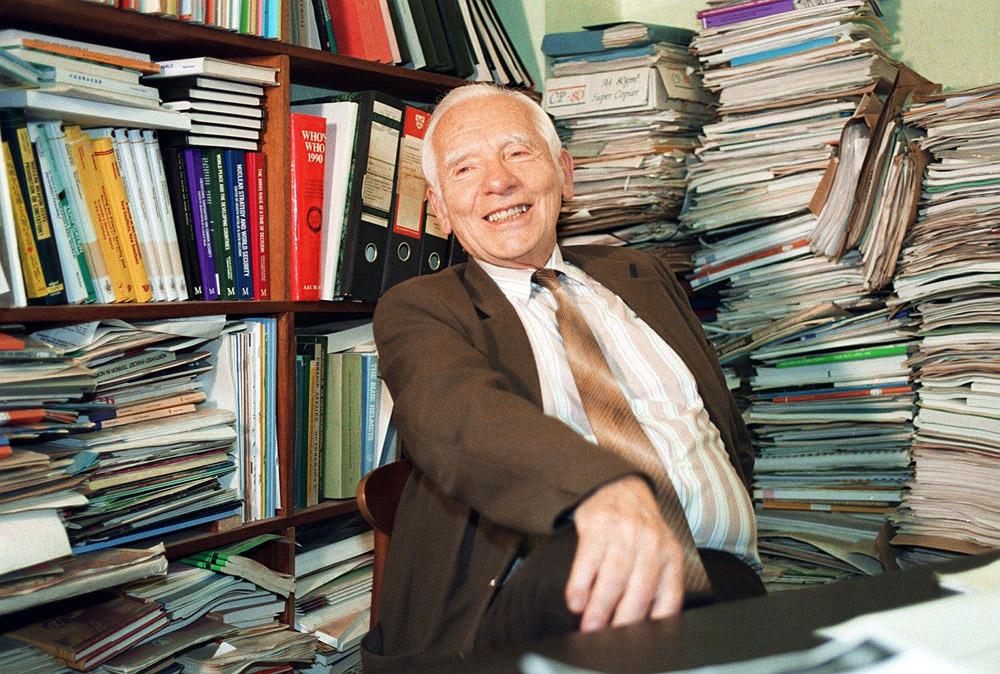

Nobel Peace Prize winner Joseph Rotblat pictured at his office at the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs in Central London, photo: PAP

Nobel Peace Prize winner Joseph Rotblat pictured at his office at the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs in Central London, photo: PAPIn 1955, Rotblat became one of the youngest signatories of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, a document that condemned the escalation of the global arms race and warned of the dangers of nuclear weapons.

The manifesto also called for the establishment of a conference that would bring together scientists and public figures to find solutions to a variety of international issues, particularly those concerning the usage and proliferation of nuclear weapons.

After its inception, the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs, as it was to be called, played a vital role in finding solutions to global conflict and addressing the problems associated with nuclear weapons. Rotblat helped to organise several of these influential conferences and continued to be involved with them until his death.

These conferences helped to provide the framework for important legislation addressing a variety of different weapons, including:

- The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (1963)

- The Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968)

- The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (1972)

- The Biological Weapons Convention (1972)

- The Chemical Weapons Convention (1993)

All the aforementioned treaties, in one way or another, have helped make the world a safer place through mutual disarmament. It was for his work with Pugwash that Rotblat received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995. In his speech, Rotblat described the objectives of Pugwash as follows:

What we are advocating in Pugwash, a war-free world, will be seen by many as a utopian dream. It is not utopian. There already exist in the world large regions, for example, the European Union, within which war is inconceivable. What is needed is to extend these to cover the world's major powers.

A Hippocratic Oath for scientists

Nobel Peace Prize winner Józef Rotblat talking to the media at his office at the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs in Central London, photo: PAP

Nobel Peace Prize winner Józef Rotblat talking to the media at his office at the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs in Central London, photo: PAPLater in life, Rotblat became particularly committed to the idea of a Hippocratic Oath for scientists. Rotblat believed that the ethical framework of the Hippocratic Oath had been of great use to the medical community and that the scientific community could benefit from something similar.

The oath, which would be taken by scientists from all disciplines, would reaffirm the scientific community’s commitment to pursuing research with noble and ethically-sound intentions. Rotblat proposed the following:

I promise to work for a better world, where science and technology are used in socially responsible ways. I will not use my education for any purpose intended to harm human beings or the environment. Throughout my career, I will consider the ethical implications of my work before I take action. While the demands placed upon me may be great, I sign this declaration because I recognise that individual responsibility is the first step on the path to peace.

As was shown in the rather extreme example of Dr. Strangelove, it was, and still is, possible for scientists to become reckless and irresponsible. The ethical framework proposed by Rotblat, though it remains but a proposition, demonstrated his commitment to ensuring that the aims of the scientific community would always be to the benefit rather than to the detriment of humanity.

Never forget your humanity

Battered religious figures stand watch on a hill above a tattered valley. Nagasaki, Japan. September 24, 1945, 6 weeks after the city was destroyed by the world's second atomic bomb attack, photo: Wikipedia

Battered religious figures stand watch on a hill above a tattered valley. Nagasaki, Japan. September 24, 1945, 6 weeks after the city was destroyed by the world's second atomic bomb attack, photo: WikipediaEven after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the spectre of nuclear conflict has not disappeared. Rotblat helped to reduce this threat during his lifetime, but he understood that much remains to be accomplished if we are to have a truly lasting peace.

In his Nobel Prize speech, Rotblat presented the global community with an alarming yet important ultimatum found in the Russell-Einstein Manifesto:

We appeal, as human beings, to human beings: remember your humanity and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open for a new paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.

Despite his dedication to promoting nuclear disarmament, Rotblat is an often-overlooked historical figure. Many people today, if asked about Rotblat, would likely be unaware of who he was or what he did, even though their very existence could arguably be attributed to his efforts.

Even if Rotblat’s name has faded into obscurity, as unfortunate as that may be, his message to the world remains as relevant as when it was spoken. His optimistic message of greater co-operation and mutual understanding may, to some, seem overly idealistic and lack grounding in reality.

Be that as it may, it remains, in every sense of the word, an ideal. It is not a solution to the problems that beset us nor does ignore the complicated realities we face. It is something we must strive for. It is something we must remain committed to, regardless of the obstacles and challenges that lie in our path.

Józef Rotblat, in all his years, never forgot his humanity. He saw mankind at its worst throughout his life, but his optimism and faith in humanity never wavered. If we are to honour this legacy of commitment and selflessness, we too must never forget our humanity.

Written by Michael Keller, May 2017

Sources: Manhattan Project Voices, OpenVault, Youtube, The Telegraph, The New York Times, Nobelprize.org