In the critical art they practiced in the 1990s, Polish artists explored the issue of corporality and its entanglement in power structures while simultaneously demonstrating interest in cultural practices that discipline. Artists focused their attention on the body seen as a realm of experimentation, a site affected by power structures, an object exposed to constant innovation, a space within which we define our subjectivity.

A number of artists initiated a kind of play with concepts of the body. They included Grzegorz Klaman, Katarzyna Kozyra, Zofia Kulik, Konrad Kuzyszyn, Zbigniew Libera, Dorota Nieznalska, Alicja Żebrowska, and Artur Żmijewski. In reassessing the visual sphere, these contemporary artists simultaneously reconsidered concepts like art, beauty and aesthetics. Thus, Piotr Piotrowski defined this art as knocking us out of automated modes of perception and thought.1

Critical Art - Concepts

The term "critical art" appeared in the late 1990s, first employed perhaps by Ryszard W. Kluszczyński.2 As imprecise as it is, the phrase seems best to describe the activities of Polish artists of the 1990s, whereas the media attention their art received, the controversies and incessant attacks it engendered, effectively revealed this phenomenon's critical force.

Critical art's tentative "critical edge" is noteworthy; the movement must not be understood as consisting of direct expressions of criticism. This art (to its own advantage) lacked anything of the sort. It was not explicit art, positioning itself within, rather than outside, the structures it criticized. Critical art of the 1990s essentially sought to produce critical descriptions of reality and to comment on contemporary life. It accomplished its critical work by revealing and divulging what is hardly obvious, subcutaneous, unclear, marginalized. We might quote Michel Foucault:

The aim of criticism is to lay bare silent messages, different kinds of habitual, indiscriminately accepted, unnoticed ways of thinking upon which the practices we accent are supported. [...] To engage in criticism is to employ difficult gestures in executing easy ones [emphasis: IK].3

This movement in Polish art certainly shared something with trends that appeared earlier and developed concurrently in the United States and Western Europe, including phenomena like "postmodern resistance," body art, or abject art. In describing the practices of Polish artists, some critics also described it as "body art" or "postmodern practice," while yet others denied these creative manifestations the status of art altogether.

Context

Ewa Partum, Exercises, 1972

Ewa Partum, Exercises, 1972The events of 1989 were the defining moment that placed Polish art in a political context. Art reacted to the political and cultural changes occurring in Poland at this time. Previously, art was perceived as universal, while the artist was seen as standing above society. Under Communism, art primarily operated outside of social reality. The legacy of Socialist Realism and the seemingly apolitical art that came immediately after (which paradoxically proved comfortable to those in power) produced an aversion to socially engaged art in any form among artists and resulted in a total absence of critical art. The art of this period altogether avoided social issues, which were seen as banal, unbefitting the concept of universal art. Though feminist intervention manifested itself a number of time in Polish art of the 1970s, the works of artists like Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Natalia LL, Ewa Partum, and Krystyna Piotrowska remained apart from the sphere of women's real problems, and their criticism of patriarchal culture failed to intersect with the social sphere.

The 1990s brought a change in attitudes toward art and in artists' stances. The new post-1989 social reality, with Poland entering a phase of accelerated capitalist development and consumer culture becoming the order of the day, affected the interest of artists. New threats, primarily emerging from the country's under-developed democracy, also appeared. Women's rights were restricted in this period, for example, through the introduction of a ban on abortion in 1993. Notably, the population seemed collectively to cease considering the concept of freedom, seemingly convinced that nothing remained to be done in this realm. Yet critical art continued to ask about freedom: Can we be free? What restrictions should there be on freedom? How do we currently understand this concept? What is artistic freedom? Art also identified newly appearing threats to our freedom (of expression, creativity, access to information, evaluation, etc.).

By revealing, dismantling our customs and habits, critical art elicited frequent controversy and heated discussion. There were instances of censorship and some artworks were destroyed. Opponents of contemporary art most often cited it as offensive to their religious beliefs. Works exploring Polish Catholicism and the influence of the Church on our reality, art tackling controversial subjects, revealing intolerance and the exclusion of Others, were seen as dangerous. Art thus became an important test of democracy. As Krzysztof Pomian writes,

Modern art, though obviously not exclusively, strongly reminds us that democracy requires differences - be they group, political, ideological, religious, or other - and disputes. Democracy's strength lies in its singular ability to take conflicts born of difference (that is, threats to collective coexistence) and to transform them into sources of cultural, social, and economic energy.4

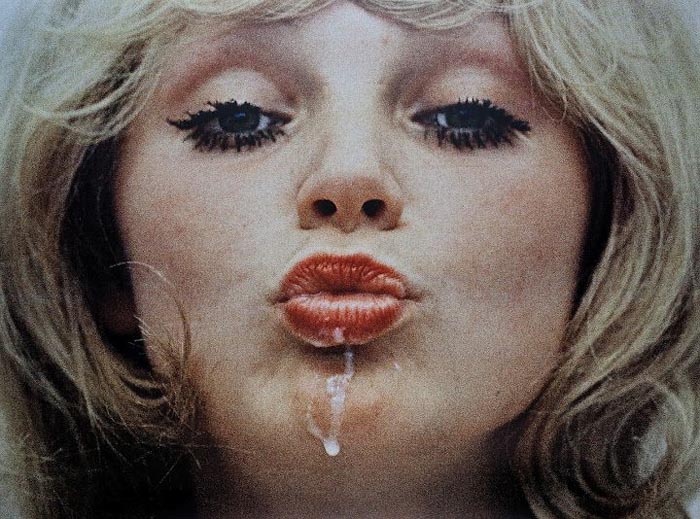

Natalia LL, Post - consumer Art, 1975 / photo: courtesy of the artist

Natalia LL, Post - consumer Art, 1975 / photo: courtesy of the artist Most importantly, critical art is not conducive to indifference and engenders discussion and the negotiation of viewpoints, which are pillars of the democratic system.

In spite of facing general opposition, Polish art of the 1990s was unusually clear in its expression and mature in its methods, making deep critical incisions into the layers of our culture. In time this art gained popularity and produced some true successes, especially on the international arena, as exemplified by the award Katarzyna Kozyra received for her Łaźnia II / Bathhouse II at the Venice Biennale in 1999.

The Body and Power

Critical art sought to analyze the mechanisms by which the body is incapacitated by contemporary culture. Artists began to employ formal means similar to those found in popular culture, began to simulate its mechanisms. Through their work they revealed the mechanisms by which the body is disciplined, shaped to match unachievable ideals, tamed and trained, embodied in terms of gender roles.

The body was not the only thing at issue in this art. It became the fundamental area of artistic discussion about human identity. Many artists, both male and female, rend gender identity problematic. The borderline states our physical existence began to be visible, liminal states like sexuality, illness and death, and thus art began to infringe upon contemporary taboos. Artists also questioned the division of identity into spiritual and physical parts and the division of the body into its surface and interior. They sowed man on the one and as an integrated unit, but on the other also as something subjected to the mechanisms of power. They demonstrated how what is defined as "universal" is a factor that excludes all non-standard forms of identity, and simultaneously how what is private, what passes as the most personal, is subjected to manipulation, is subject to the control of power.

The reasons why some artists, critics, and theoreticians demonstrated an interest in the issue of the body in the 1990s are complex. One could indicate the new manners of functioning of the body in consumer culture: thus the possibilities for manipulations to be carried out on the body became ever greater (like the improvement of bodily intervention techniques, transplantation, as well as the possibility of cloning humans). Cyberspace also began developing at a break-neck pace, further changing our perception of corporality. Also noteworthy were the popularity Michel Foucault's theories, the influence of Gilles Deleuze's theory, Jacques Lacan's psychoanalysis and feminist theory in most humanist realms and generally in the domain of contemporary culture.

The concept of power to which contemporary critical art directs our gaze shares much with that presented in the theories of French philosopher Michel Foucault, who wrote about micro-power, internalized power, power that manifests itself at the corporal level. 5 These theories demonstrate the existence of various types of power, like that, for instance, which is related strictly o knowledge, that restrictions dictated by centers of power are embedded within us, in a manner that prevents us from escaping these mechanisms.

Zofia Kulik - Deconstructing Power

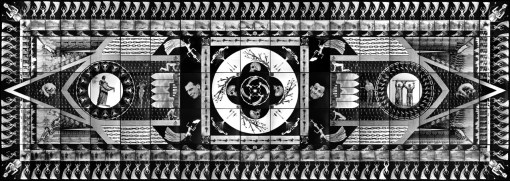

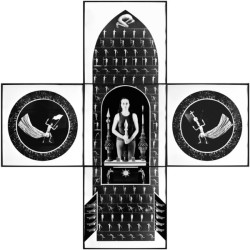

Zofia Kulik Wszystkie pociski są jednym pociskiem / All Shells are One Shell 1993, 304x855 cm, photo: courtesy of the artist

Zofia Kulik Wszystkie pociski są jednym pociskiem / All Shells are One Shell 1993, 304x855 cm, photo: courtesy of the artistFoucault's theories quite significantly influenced the work of Zofia Kulik (b. 1947) (including Gotyk Między-Narodowy / Inter-National Gothic, 1990; Wszystkie pociski są jednym pociskiem / All Shells are One Shell, 1993), in which a nude male body is inscribed into ornamental structures resembling mosaics, rugs, Gothic windows or altars. This art becomes a metaphor for subjecting the human to centers of power. The question regarding the limits of our enslavement is most important in Kulik's work. Is individual freedom still possible in a world that is so structured? Complete human incapacitation occurs within totalitarian systems, which the artist perceives as most threatening. These systems aim to exercise control over the entire human being - his or her body and consciousness (mind). They take control of to the extent that humans lose awareness of their dependency. Yet the danger resides not only in totalitarian systems, but comes with any form of power. In one of her statements, Zofia Kulik expressed her helplessness relative to the force to which she was subordinate, relative to, as she terms it, the "hammering." Escape from this predicament might be found in describing it, revealing the operative mechanisms of power, extracting its structures from the sphere of the invisible. This is precisely the kind of description that Kulik accomplishes through her ordered, decorative, patterned tabloids, through structures that organize human life. She simultaneously reveals the phallocentrism that is at once inscribed in them and simultaneously entirely neutralized. She often accomplishes this through subversive methods, as in the work Wszystko się zbiega w czasie i przestrzeni, aby się rozproszyć, aby się zbiec, aby się rozproszyć, no i tak dalej / Everything Converges in Time and Space, Only to Disperse, to Converge, and So On (1992). The work is dominated by the figure of a dressed woman standing directly opposite the beholder and gazing at him. In her hands she holds the metal fitting from the end of a banner pole. Closer to the center of the work, this image is surrounded by horizontal stripes composed of images of a nude man who strikes many different poses while holding a long, vertical object in his hands. Further toward the edges of this "altar" created by Kulik is an oval pattern that features the figure of the same man lifting his hands as if in a gesture of adoration or submission.

Zofia Kulik, Everything Converges in Time and Space, Only to Disperse, to Converge, and So On (1992), photo: courtesy of the artist

Zofia Kulik, Everything Converges in Time and Space, Only to Disperse, to Converge, and So On (1992), photo: courtesy of the artistThe woman in Everything Converges in Time and Space... retains the power of the gaze as well as the power of occupying a privileged space. All elements of this representation are subordinate to her. She appears in a space reserved for those who retain power, which under within the patriarchal order was occupied by the male observer, but which, as in the panopticon described by Michel Foucault, remained invisible. She renders this space visible. By assuming male attributes, the artist accomplishes a kind of symbolic "castration" of power, rendering the privileged place visible and demonstrating that power distributed according to gender divisions is a construct.

In Kulik's works, undressing deprives humans of their protective layer, reveals the illusiveness of gestures that denote strength and power in our culture. She demonstrates that adaptation to the system occurs at the corporal level. Undressing thus denotes rendering harmless, disarming, revealing the fragile nature of the symbols of power. This is the same as in the motif from the Ikonograficzny przewodnik / Iconographic Guide to the work titled Wszystkie pociski są jednym pociskiem / All Shells are One Shell: the artist took Lenin's pose from the statue by Alekseyev - a pose itself drawn from the Classical iconography of the speaker/orator, a pose connoting power - and juxtaposed with the same pose struck by fellow artist Zbigniew Libera, presented in the nude. When power disappears, all that remains are absurdity and the artificial themselves.

Kozyra - Excluded Bodies

Katarzyna Kozyra (b. 1963) also explored the problem of power in her works. Więzy krwi / Blood Ties (1995), Olimpia / Olympia (1996) and both Łaźnie / Bathhouses (1997 and 1999) expose the strategies of exclusion that pervade our culture, pointing to the exclusion of those who are ill, aged, disabled. The artist directs our attention to the issue of the visibility/invisibility of specific types of bodies and the inscription of the body in various constructs of power.

Katarzyna Kozyra, still from the video Bathhouse, photo: courtesy of the artist and the Zachęta Gallery

Katarzyna Kozyra, still from the video Bathhouse, photo: courtesy of the artist and the Zachęta GalleryIn Więzy krwi / Blood Ties (1995) Kozyra depicts women as the victims of acts of war. The nude bodies of the artist and her lame sister are inscribed in representations of a cross and a crescent - simultaneously symbols of Christianity and Islam, and of humanitarian assistance, Kozyra admits that the work was influenced by events in former Yugoslavia. The cross and crescent appear here as emblems of fratricidal fighting against a background of religious and ethnic conflicts. The cauliflower and cabbage heads, perhaps the most puzzling elements of these compositions, might be seen on the one hand as a reference to nature's fertility, with which womanhood has always been associated, and on the other as a reference to the fields of former Yugoslavia - places where the victims of mass/collective murder, but also sites where Muslim women were raped.

Kozyra's work demonstrates the enslavement of a human being, who from birth is inscribed in a given system. The figures in Blood Ties seem defenseless; they become victims incapable of escaping the places to which they were assigned, of extracting themselves from the system imposed on them.

Illness and old age are another important issue that Kozyra explores in her art. Olimpia / Olympia (1996), referencing Édouard Manet's well-known canvas from 1863, is composed of three photographs: one of the artist posing like the prostitute in Manet's painting, another of the artist lying in a hospital bed, a nurse and an IV on a stand at its side, and a nude old woman sitting in a chair. These images are accompanied by a video which in visual terms is most akin to the second photograph, presenting the artist undergoing a series of medical procedures while partaking of a substance intravenously.

The meanings of this work are related to the issue of visibility (of a specific type of body) and invisibility (bodies contrasting with the ideal). The artist forces us to think about why it so difficult to view frail and old bodies, why we assume that these images are taboo, that old age, ugliness, and illness should not be placed on display. Kozyra thus demonstrates how our unwillingness to look leads to striking given issues from our minds. The Olympia series also evokes the mortality of the body, revealing the illusiveness of our control over it.

Similar meanings are conveyed by the video installation Łaźnia I / Bathhouse I (1997). This work was composed of five monitors and one projection screen, upon which was shown a film which the artist recorded using a hidden camera at a bathhouse for women in Budapest. The monitors and screen were set up so as to surround the viewer. The filmed women, young, old, with bodies mostly differing from the ideal, circulate about the bathhouse, taking baths, washing themselves, recline inside a sauna, speak to each other, dry themselves with towels. They are unaware of being observed by an external eye. As a result, they neither pose nor care to strike poses in which they believe their bodies look best. Yet they also observe each other. We can, however, assume that their behavior would be entirely different if they knew they were being watched by a male observer. If they suddenly gained awareness of the hidden camera, their gazes would surely be as terrified as that of Zuzanna from Rembrandt's canvas (1647), shown toward the end of the film projection on the large screen in the midst of the monitors. In this painting, Zuzanna gazes resentfully at the observer, thereby drawing him in directly to the represented action, drawing links between the beholder and the aged individuals in the imagery. Her gaze is thus accusatory: even though the images of the women may be a source of anxiety or embarrassment, we gaze at them with interest. The beholder is unmasked, inscribed into the construct that is this work, and additionally becomes a potential victim of the artist's attack, a potential object of her observation/action.

Kozyra created Łaźnia II / Bathhouse II especially for the 1999 Venice Biennale. The work consisted of four screen set up to form an octagon (with the remaining four walls formed by the passages between the screens). The films projected on the screens, this time recorded in a men's bathhouse in Budapest, could be watched both by those inside and outside the geometrically shaped space. The work was accompanied by a video playback revealing, in very close detail, the manner in which the artist's body was made up to resemble a man's.

By entering the men's bathhouse in a "male" body subverted the established/obviousness of gender divisions organized based on biological difference. Biology was no longer a barrier for her, it was enough to rebuild the body in a manner allowing it to resemble externally the emblematic image of the opposite sex. The danger of the masquerade and the radical gesture consisting of transplanting a phallus to herself, demonstrated the "constructed nature" of the human body and gender difference. In this manner her gesture became socially threatening, subverting social divisions and turning power relations upside down.

Through the differing layouts of the women's and men's bathhouses, Kozyra revealed gender-related constructs, the equating of women with the private sphere and men with the public sphere, and the culturally imposed, variegated forms of behavior deriving from this. These two bathhouse worlds are different. In the case of the first, the bathhouse becomes a bathroom - a private place for completing ablutions and other bodily care processes. In the second instance, the bathhouse is a meeting place and a social club. All who enter are observed and gaze at each other with interest. In this manner Kozyra dismantled John Berger's hypothesis claiming that men observe and women put themselves on display.6 As it seems, women also observe each other while men can also be the observed.

In subsequent works Katarzyna Kozyra expanded her exploration and juggling of ambiguous roles, masks and genders, raising serious doubts about some of the most obvious lines of division (e.g. Ragazzi, 2001; Boys, 2002; Punishment and Crime, 2002).

Żebrowska: Constructs of Sexuality

Alicja Żebrowska, still from the video Primal Sin

Alicja Żebrowska, still from the video Primal SinFeminine sexuality, the manner in which it is defined and represented, are explored broadly in the works of Alicja Żebrowska (b. 1956), and especially in the installation Grzech Pierworodny / Primal Sin (1994) and the photograph that accompanies it titled Narodziny Barbie / Barbie's Birth.

The first version of Primal Sin, which was sub-captioned Domniemany Projekt Rzeczywistości Wirtualnej / An Assumed Virtual Reality Project was a video installation whose dominant element was a green apple. The first segment of the film focused on a girl eating an apple, and it was followed by scenes presenting the sexual act, with the imagery limited to demonstrating the sexual organs. In this work the artist equates a symbol of the first woman eating an apple with the sexual act, and extracts the act itself from the sphere of invisibility and inaudibility.

The second version of Primal Sin was a rebellion against the castigating words of God, uttered to the first woman, which denoted subordinating her to a man and burdening her with the pain of childbirth. The initial scenes of the film relate to the artist's childhood sexual experiences with a friend with whom she used to play. These experiences were accompanied by contradictory feeling: joy at the pleasure experienced and deriving from the process of exploration itself, and embarrassment and fear at the discovering/possibility of being discovered and unmasked this pleasure. From their youngest years, as they are brought up, girls receive messages that the sphere of sexuality is "embarrassing", "dirty". The fear Zebrowska explores is fear of the all-seeing eye of God, which in the film is nevertheless presented as blind: as a button surrounded by a woman's vulvar lips. Subsequent scenes of the film are limited to presenting a woman's vagina and the pleasures it experiences. The tool providing pleasure is not a male member, but an artificial penis or the woman's own fingers. These images are intertwined with scenes of mud-baths used in treating certain uterine conditions, which here evoke images of menstruation or a woman's water breaking prior to when she gives birth. All this prepared viewers for the most important sequences, which consisted of scenes of a simulation of a birth, where the newborn is replaced by a Barbie doll.

Żebrowska's works point to the power of the myths connected with female sexuality perceived as a sin and with contemporary beauty-focused myths embodied in the Barbie doll. The artist demonstrates that the sexuality of a woman operates in the social sphere as a taboo and just how ambivalent attitudes to this sexuality are. Women are shown as elevated, set on a pedestal, eliciting desire, yet their sexuality evokes fear and disgust. This does not cancel the desire to learn about this sexuality, except that this desire is demoted to a forbidden sphere, i.e. the domain of pornography. The image of female sexual organs has been relegated to this sphere defined as something unofficial, forbidden, dark, unclean.

In her work, the artist violates this system, introducing into the sphere of art something that is "obscene", something that was excluded from this sphere, and even though she employs almost pornographic methods, she also succeeds in dismantling that construct, as in this work the pleasure of watching is eliminated - quote the contrary, Żebrowska's images are disquieting, elicit fear, cause disgust. The result is a clash of various constructs of female sexuality: that of the fulfillment of male needs, that of something terrifying, eliciting fear, something sinful, but subject to control and the mechanisms of power, and also as an intimate experience of pleasure. This work violates a cultural taboo, encroaching upon a domain that has thus far been forbidden. Primal Sin acquires additional meanings when considered in the Polish context, within which female sexuality is often the object of political manipulation.

Żebrowska also utilizes other forms of gender that have been completely pushed out of repressed from the public sphere. In her photographs of the Onone. A World after the World series (1995-97), the artist produces a utopian world where the distinction between two genders does not exist. In this manner Żebrowska breaks the dualistic division of genders, seeking out transgressing bodies that weaken and subvert the binary opposition so deeply implanted in our culture. Instead of this, she offers freedom in the construction of one's body and gender

- what occurs is an implementation of one of the cybernetic utopias about the new perception of identity, where the old divisions disappear, the significance of the body is changed, and the body-machine acquires great significance.

Through her works Alicja Żebrowska highlights a certain policy of sexuality, the repressive nature of authority and its effects (including negative and terrifying images of female sexuality), she strives to reveal all that has been relegated to the spheres of silence and privacy, all that has acquired a negative taint in our social context.

In her art Żebrowska has also explored the problem of infirmity, frailty, defects. In the work titled Przypadki humanitarne / Humanitarian Cases (1994) she shows two girls: one with a disability, sitting in a wheelchair, dressed, the other, touched by no infirmity, standing behind the chair, nude. Through this work the artist highlighted the issue of what we are accustomed to in relation to our perceptions of a woman's body, the image of which serves as a source of pleasure for the beholder. Here we must deal with a juxtaposition of these habituations with a view of a frail, disabled body, a view that most often causes us to turn our gaze away.

Żmijewski: Frail Bodies

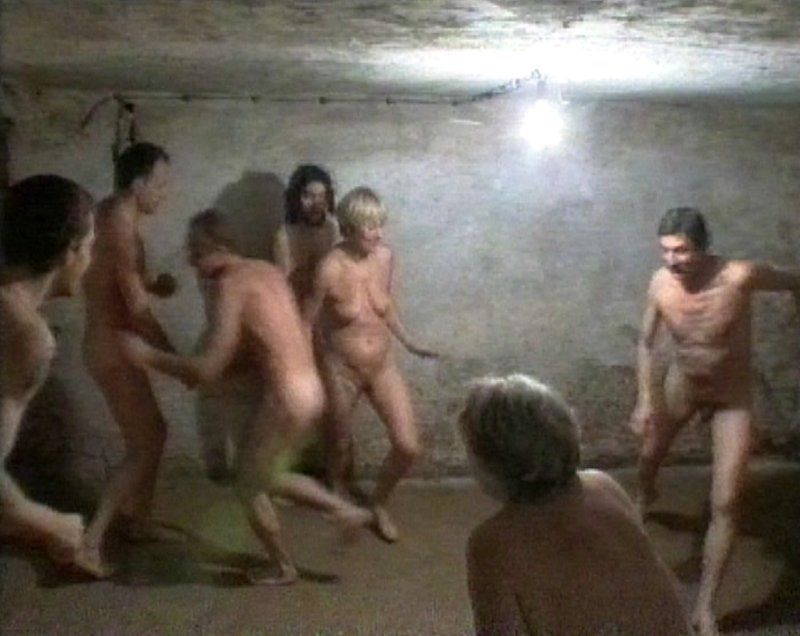

Artur Żmijewski, still from the video Tag, photo: courtesy of the Raster Gallery

Artur Żmijewski, still from the video Tag, photo: courtesy of the Raster GalleryThe issue of the body's mortality, its frailty, iniquity, illness, became one of the key issues of the art of the 1990s. It is likewise the chief issue explored in the works of Artur Żmijewski (b. 1966). The artist perceives art as a form of exploring reality, social relations, human relationships, the imprisonment of humans in conventions, dependency on various forms of authority/power. On principle, the artist moves about marginal, rejected areas. He seems interested in the human condition and the manner in which it functions under extreme circumstances, in situations of debasement or even coercion.

In his art he features "Others" - humans rejected and thrown out of the visible field. His video works feature individuals with disabilities, illnesses, handicapped children (Ogrod Botaniczny/ZOO / Botanical Garden/ZOO, 1997). These actors resist accepted norms, refuse to maintain the socially imposed distance between each other. The body becomes a tool for learning about and exploring another human being, just as it was in one of the artist's first works, entitled Powściągliwość i praca / Reticence and Labor (1995), or another, somewhat later work shown in the exhibition Ja i AIDS / Me and AIDS (the video work in question had the same title, 1996).

The problem of the physical limitations of the body is something Żmijewski returns to in his works several times. In his videos, he shows the dramatic struggle with the body that is partly disabled, afflicted by illness, dying. It is a struggle for life, as well as for functioning among one's dear ones and in society.

The best known work focusing on this subject matter was the series Oko za oko / Eye for an Eye (1998), consisting of a video and a number of photographs. In this work the artist produced a vision of positive symbiosis of unimpaired and impaired individuals, where the differences between these two categories become/are rendered fluid, illegible. In this manner creatures are created, where the difference between an unimpaired body and an excluded, "Other" body is blurred, and the division into what is normal and what is excluded by norms, what finds itself beyond the boundaries of the norm, ceases to be valid. Those with disabilities do not hide their impairments here. Yet only through learning about the "Other" may they be included in the whole. In his work, Żmijewski does not negate the impairment, including it instead in the closed realm of social relations. In this work, the "Other" ceases being that other, becoming instead a part of the whole, an irreplaceable element of the system and scheme.

Learning about the "Other" occurs through touch, physical contact. This is what occurs in the video work Sztuka kochania / The Art of Lovemaking (2001), which shows individuals in situations of demonstrating mutually to each other love, tenderness, warmth, devotion. What we see her are aged people, individuals afflicted with Parkinson's disease, and a Down syndrome couple. Corporal limitations (trembling hands, bodies ravaged by illness) must be overcome to enable touching a dear one, embracing them, kissing them. Żmijewski demonstrates how difficult thinking about corporal love can be where the aged, ill, or disabled are concerned. Their corporal limitations are also - and perhaps above all - a problem for those who behold their love.

Żmijewski also explores the toilsome struggle with the body in his work titled Na spacer / Going for a Walk (2001), which shows attempts at walking made by paralyzed men. With the help of a rehabilitator, the men gain the possibility of "walking". This walking, a common activity, causes the paralyzed men incredible pain, takes effort beyond the measure of their abilities. Bodily limitations seem impossible for overcome, and the effort made seems condemned to failure.

Żmijewski also seems to depict unavoidable failure in his film titled Karolina / Caroline (2002), which shows an 18-year-old girl who suffers from advanced stage osteoporosis. The girl incessantly suffers to the continuous sifting within her body of fragments of broken or crumbled bones. We observe her struggle against the pain, which exceeds our imagination. The artist depicts the act of dying in its most terrifying aspects: suffering, solitude, abandonment of all hopes of being cured.

"It is a shock that the possibility of defeat resides permanently within the body", the artist states in one of his interviews, positing this as one of the problems that occupies him.

However, the artist also seeks out those situations where corporal limitations can be overcome, where something occurs that seems contrary to logic and reason. This is demonstrated in Lekcja śpiewu / Singing Lesson (2001), where deaf and hearing impaired children for whom sound and music are fundamentally strange, not understandable, and therefore abstract. The artist thus forces us to consider the categories that we employ in thinking, demonstrating that these categories are hardly universal.

In his art Żmijewski also explores the issue of our memory of war; he seems to ask outright if the Holocaust can be imagined. In the film Berek / Tag (2000), nude people play the game known as "Tag" in dark interiors, probably cellars. The concluding title informs us that these scenes were recorded in a space that formerly served as a gas chamber in one of the extermination camps. Through this work the artist asks not so much what happened in the gas chambers, what the people awaiting death did inside them, but whether our imagination is capable of accommodation and bearing consideration of the topic.

In other works, this artist explores memory, asking about the extent to which past traumas persist within us, how they affect us. One of Żmijewski's most controversial pieces is 80064 (2004), a film which shows the artist persuading an elderly man, formerly a concentration camp prisoner, to have his prisoner's number, 80064, tattooed once more on his arm. The piece simultaneously proves to be about traumas that are inscribed on our bodies.

Nasz śpiewnik / Our Songbook (2003) is another piece that explores the concept of memory. For this work, Żmijewski asked elderly Jews of Polish origin living in Israel to try to recall and sing at least bits of Polish songs they knew when they were children.

The artist also seems to be interested in how human beings behave when forced into a humiliating situation, dragged through the mud, their freedom limited. KR WP / HG PA (2000) is a work that explores conventions that restrict our behavior. In this work the artist showed former members of the Polish Army Honor Guard who are drilled, present arms, sing marching songs. They perform some of these activities in the nude (or merely in army boots and caps). Żmijewski demonstrated how strong the mechanism is that virtually automatically associates nudity with shame, derision, humiliation, and thus demonstrated that the body is the site of the gravest enslavement, discipline, and simultaneously demonstrated the fragile nature of the meaning of force and power inscribed in the construct of manliness.

Kuzyszyn: The Human Condition

As if in conscious contradiction to non-reflective and shallow popular culture, contemporary artists also seek to explore the human condition as a concept and in its manifestations. Konrad Kuzyszyn (b. 1961) has made this the focus and core subject matter of his works. The artist's work known as Kondycja ludzka / The Human Condition is actually titled Exi(s)t (1989) and consists of photographs taken at the Collegium Anatomicum in Lodz, images in which preserved human corpses become an object of artistic analysis. The artist effectively accomplishes a "personalization" of his subjects, creating photographs that are not of corpses used for medical study, but that present the deceased individuals, capturing facial expressions, almost showing their feelings. The work's topic seems to be the problem of the death experience, as well as the functioning of is perceptions. In our culture we negate mortality, seek to strike images of it from our daily experience. As a result, photographs like those of the Exi(s)t series terrify us, forcing us to reflect on our own fear of death. This is a horrifyingly beautiful work. Yet it leaves us wondering if these bodies so completely appropriated by medical discourse, serving as they do scientific discovery, if they can possibly tell us anything about our existence, our lives, or rather - if we are capable of understanding what it is they convey.

In subsequent works from the Human Condition series, the artist depicts bodies whose boundaries dissolve, multiply in and of themselves, are multiplied by external factors. With body contours blurred or multiplied, several bodies seem to melt into a single entity. The works of Konrad Kuzyszyn are about crossing boundaries - boundaries between individuals, the boundaries of one's own body, and ultimately the boundaries of human existence. The human condition is presented as invariably entailing fear and terror. The figures Kuzyszyn presents evoke fear and anxiety; they most often appear curled up, stooping over - as if they feared their very own existence.

Klaman - The Body in the Context of Medicalization

Grzegorz Klaman, photo: Michał Szlaga/Reporter/East News

Grzegorz Klaman, photo: Michał Szlaga/Reporter/East NewsThe problem of power and its appropriation of the body, including the dead body, was also the subject of Grzegorz Klaman's (b. 1959) art, the beginnings of which date to the early 1980s. Klaman's oeuvre can be divided into several periods: from neo-Expressionist sculpture, through the concept known as "reverse archeology," which involved the artist discovering a space for himself on the Wyspa Spichrzów (Granary Island) in the port district of Gdansk, where in the mid 1980s the artist founded the "Wyspa" [Island] Gallery, to his wooden and sheet metal forms known as Monumenty / Monuments, followed by his installations incorporating human body parts, and finally his photographs of human corpses and embryos, to his discursive project in which the artist employs quotations from a number of Michel Foucault's books.

Emblematy / Emblems (1993), Katabasis (1993), Fundament / Foundation (1994), Anatomia polityczna ciał / The Political Anatomy of Bodies (1995) are objects formed of steel sheets constituting the casing for human body parts and organs conserved in formaldehyde, including a brain, liver, intestines, eye, ear, and the like. The artist is interested in the ways in which the dead body and its innards are customarily portrayed, and in our attitude to human remains. His photographs depict details of bodies, the faces of the deceased and human embryos (Biblioteki / Libraries, 1999, and Anatrophy, 1999). The artist above all directs our attention to the body's appropriation by medicine, science and symbolic systems.

Emblematy / Emblems (1993), one of Klaman's most important works of the 1990s, is worth closer examination. This installation takes the form of a steel object that is quadrangle the interior of which is accessed through a rectangular entrance. Inside, opposite the entrance, stands a container shaped like an elongated rectangle containing preserved intestines, on the wall to the right there is a container shaped like the arm of a swastika containing a preserved liver, on the left a cross-shaped container containing a preserved brain. In the darkened interior, the containers with the preserved organs are illuminated by halogen lamps. The large form of raw sheet metal strongly contrasts with the organs inside the containers.

The human organs in Emblems, imprisoned in forms referencing various cultural orders, testify to the control of the body that has been taken by symbolic orders: by culture, science, medical knowledge. These organs are displayed, becoming the objects of gazing - a kind of show. They resemble teaching aids used at medical academies. There is a religious reference as well, as they also resemble religious relics. Klaman creates a kind of temple, where gazing at the body becomes a kind of access to some secret. To see these relics, one must enter the metal form. The darkness and silence inside favor concentration and contemplation. This is a temple of knowledge. Klaman references methods related to the taking control of the body by centers of power/knowledge. He describes how the body operates in these domains. In his art he strives to reflect the symbolic structures of power over the body, to deconstruct said structures.

Nieznalska - Training in Masculinity

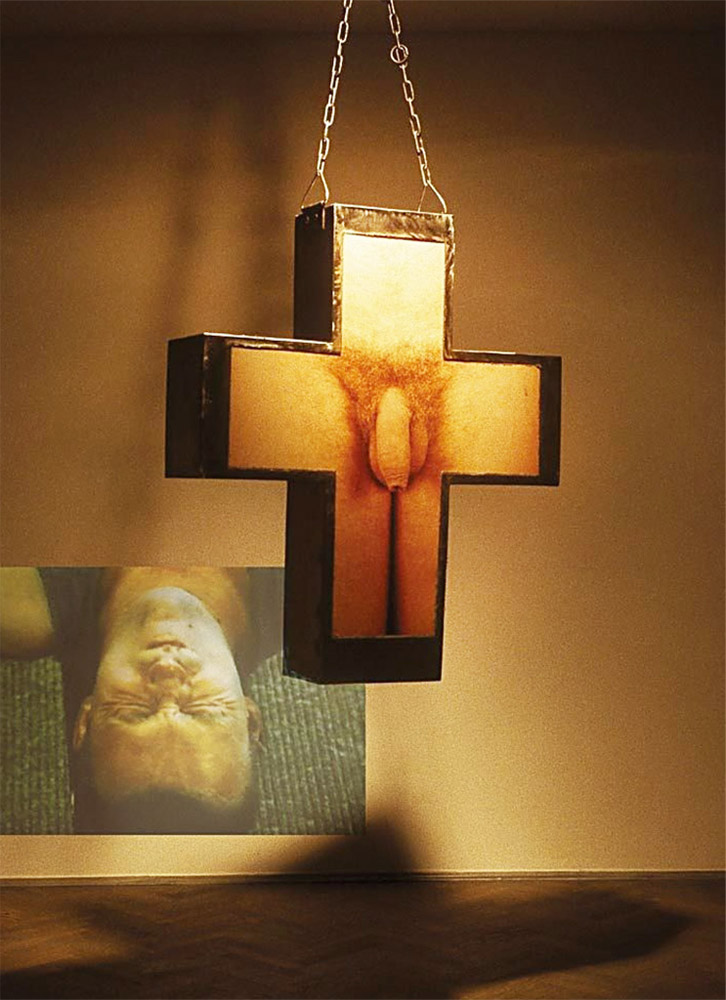

Dorota Nieznalska, The Passion, 2001, installation, steel, color photograph, video with no sound, 45 min., 104 x 92 cm, photo: courtesy of the artist

Dorota Nieznalska, The Passion, 2001, installation, steel, color photograph, video with no sound, 45 min., 104 x 92 cm, photo: courtesy of the artist

The use of critical methods is also evident in the work of the younger artist Dorota Nieznalska (b. 1973), one of Grzegorz Klaman's students.

Among others, the artist explores the topic of relations between the victim and the perpetrator, their mutual, emotional dependence, she speaks of the links between the victim and the perpetrator [Untitled (Suka / Bitch), 1999], and of the mark which the perpetrator makes on the mind if the victim (Modus Operandi, 1998).

The thing described in her later works becomes a singular kind of manhood. Potencja / Potency (2001) is a photograph that depicts a young man flexing his muscles, demonstrating a fist that symbolizes his strength. This ideal, as Nieznalska demonstrates, elicits both admiration and fear. This emotional ambivalence also appears in the installation Wszechmoc: rodzaj męski / Omnipotence: Masculine (2000-2001), which depicts a fitness room where people undergo training in manhood (symbolized by the phallic endings of the grips on exercise equipment). The sound-track for the installation, recorded by the artist at a fitness center for men, consisted of sounds of huffing, groans, cursing, and have clear sexual connotations. The artist also references these links between aggression and sexuality in the intense red lighting that illuminated the installation as a whole.

Nieznalska's best known work is the video installation Pasja / The Passion (2001), above all because of the scandal that accompanied the display of this work, and the charging of the artist with the crime of offending religious feelings and the as yet unresolved court case. This work related to the dual meaning of the term "passion", which can be understood as a process of suffering or as devotion to something as a result of having a "passion for it". The installation was accompanied by a video depicting a man training with weights in a fitness room. In this work Nieznalska focused on the problem of "manhood" (from whence the incorporation of an image of male genitalia), which must be trained, exercised, for reigning models to be met. Men who subject themselves to weight training simultaneously subject their bodies to torture, doing this with devotion/passion, often enduring a not so insignificant measure of suffering in the process. Additionally, the combination in the work of a cross and a fitness room points to a clash of religious values and consumer culture. Religion begins to answer to the laws that govern consumer culture (the "hunt" for consumers/worshippers transpires according to similar principles), while religion itself and its attributes begin to be used in consumer culture (e.g. in advertising). This work demonstrates that consumer culture is becoming the new "religion" the temples of which might include fitness centers.

In her works, Nieznalska focuses her attention on manliness, describing it through contradictory significations - as something fascinating on the one hand, and as a source of anxiety and fear on the other. The artist depicts relations based on violence and aggression. That is why her works are saturated with variegated, ambivalent meanings: at once criticism, fear and admiration of manliness.

Art and Religion (Jacek Markiewicz, Katarzyna Górna, Robert Rumas)

Robert Rumas, Hot - water bottles, 1994, Gdańsk, the Wyspa Gallery, photo: www.robertrumas.pl

Robert Rumas, Hot - water bottles, 1994, Gdańsk, the Wyspa Gallery, photo: www.robertrumas.plSome critical artists began exploring subject matter lying in the domain of religion. In choosing religious topics, they turned our attention to areas of our life (both private and public) impacted both directly and indirectly by the Catholic Church and religion itself.

This subject matter was most strongly highlighted by the exhibition "Irreligia. Morfologia nie-sacrum w sztuce polskiej / Irreligion: The Morphology of the Non-Sacred in Polish Art" (Brussels, October 2001 - January 2002), which showed the problematic significance of religion in Polish society and art. It was at this time that the concept of "Irreligion" gained popularity, a term imbued with various, often inwardly contradictory meanings. Translated literally from Latin, the term denotes "godlessness," yet it also relates to unorthodox attitudes or various forms of transgression. Irreligion indicates a liminal, marginal space, something that still relates to the religious realm but also ventures beyond it, something that plays out in the space between sacrum and profanum, effectively linking these spheres.

Works pointing to this domain "in between" included Madonna by Katarzyna Górna (b. 1968) and the photographs of Jacek Markiewicz (b. 1964), presenting a series of prison tattoos (2001), several of which had religious themes. The work of both Górna and Markiewicz emphasized corporality - a sphere that religions generally treat as impure or inferior; the works seemed to speak against the negative tainting of corporality, while Górna additionally explored the issue of religions' negating of female physiology. In her photographs from the Madonna series (1991-2001), Górna highlighted all things corporal - focusing on a trickle of blood descending down the inside of a young girl's leg, but also by depicting the young, beautiful, sensual body of a girl who adopts sits in the pose of the Madonna and child, and finally, in the third image, Górna references the convention of the Pieta - showing us a body at the threshold of old age, a body doubtlessly aged by multiple births, breast feeding, lack of time to take care of herself. The artist indicates that she was inspired to create these works by the contradictions that reign in our reality: the idealization of women and their comparison to the figure of the Virgin Mary on the one hand, and their objectification and instrumental treatment on the other.

Artists seem to ask questions about "applied Catholicism," which is characterized by superficiality and an emphasis on gestures and symbols. In particular Robert Rumas (b. 1966) explores this issue in his art. In works like Dedykacje / Dedications (1992), Termofory / Hot-water bottles (1994), 300 słoików / 300 Jars (1994), and Holy Mother (1994) the artist uses devotional items as his raw material, almost invariably packaging them, enclosing them in objects like jars or aquariums These works reference the banal nature of devotional items, cheap, kitsch objects that some Catholics treat with incredible veneration. In these works Rumas criticizes the superficial nature of Polish Catholicism, which consists in assigning the greatest significance to external manifestations and symbols. In Termofory, exhibited in 1994 in the city center of Gdansk, the artist showed plastic, water-filled bags containing plaster votive figurines of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. This work was destroyed within minutes of being installed in the main pedestrian area of the city. The destruction was the work of passers-by, who ruptured the bags, removed the figures and then took them to the office of the Gdansk diocese. These people acted under the conviction that the work was blasphemous and that the figurines could only be "saved" by returning them to their rightful place (a church). This action on the part of an anonymous crowd revealed the power of devotional/votive items, the authority religious symbols hold in the minds of people. A similar act of destruction occurred in Belgium while the Irreligion exhibition was on view.

Libera - Consumer Training

Zbigniew Libera, Intimate Rituals, photo: courtesy of the Raster Gallery

Zbigniew Libera, Intimate Rituals, photo: courtesy of the Raster GalleryI have chosen to discuss the art of Zbigniew Libera (b. 1959) at the end, because at least part of this artist's output seems to delineate new areas of interest characteristic of the art that appeared in Poland after the year 2000. It should be noted that many of Libera's works were decidedly ahead of their time, for which reason this discussion will also cover pieces which the artist produced in the 1980s.

One of them is the video Obrzędy intymne / Intimate Rituals, dating from 1984 (but first shown in 1986), recording the activities involved in caring for an ailing, dying person, specifically the artist's grandmother. We see her incessantly in one place - her bed. The illness that has touched her requires her to be cared for at all times - she must be fed, changed, bathed. We become voyeurs of some of the cruelest aspects of our existence - old age, illness and dying. Libera shows us the gradually expiring woman in her environment. In the case of this work, death is not relegated to the medical domain, rather, it belongs to the private sphere and transpires in silence. It is the kind of death that is not generally spoken of. It is something that is simultaneously shameful, embarrassing, painful, and terrifying. And the artist renders all this visible.

Libera was also the artist to grant shape to the issue of consumer culture. In the 1970s and even in the 1980s in Poland, products characteristic of consumer culture were associated with affluence, scarcely available luxury, with the freedom to buy and choose [Ciotka Kena / Ken's Aunt (1995)]. Consumer culture is characterized by an insatiable need to make use/take advantage of available goods and pleasures. Thus the power that is concealed in this system is so difficult to define and delineate, for it is based on that desire for pleasure. As Libera demonstrates in his art, omnipresent consumerism affects all aspects of life, shapes them, influences the perception and definition of our identity.

One of the artist's best known and most controversial works is Lego. Obóz koncentracyjny / Lego - Concentration Camp (1996), in which the artist pointed out the commercialization of the Holocaust, the fact of it being turned into a "source of entertainment". The artist seems to have combined contradictory concepts that might seem impossible to reconcile: the reality of concentration camps (a reality that many contend cannot be represented, is unimaginable) with the reality of children's toys (thus, a world associated with innocence and safety). Can we possibly imagine children playing with these toys? It seems probable, as our culture seems to have admitted and now offers many toys and games that involve or explore violence. Children often play what seems most drastic, and exhibit no inhibitions at the prospect of utilizing reality in play. Plastic machine guns, popular films and games about wars cause an indifference to death and war. In these works the artist revealed the practice of taming violence that takes place in our culture and our culture's arrogance relative to other cultures or distant, historical events, including those that are appropriated by popular culture (for example, gadgets being replicas of artefacts on view at a museum of Medieval torture). The work points to a consumer culture where everything is sellable, even some truly horrific and tragic events. In addition, Lego - Concentration Camp poses questions about our memory of the Holocaust, what is this unimaginable event to young people, for whom it is already the distant past, to people who increasingly live in a virtual world. In this form - as Lego blocks - can the Holocaust become something closer, more palpable, can it prompt them to think and reflect?

Zbigniew Libera, Lego. Concentration Camp, 1996, photo: the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

Zbigniew Libera, Lego. Concentration Camp, 1996, photo: the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw In other works Libera notes the process of our adaptation to culture, and even points to hidden "training" mechanisms. In the 1987 video titled Jak tresuje się dziewczynki / How Girls are Trained the artist demonstrated how traits considered desirable for representatives of a given gender are embodied. Training methods, the process of learning feminine appearance, are presented here as something unusually attractive to a five-year-old girl. Her body becomes a realm of controlling womanliness, imposing from early childhood standards of discipline related to her physical appearance. The girl seeks to be attractive at all costs since she knows that she is evaluated through her appearance, she knows the recognition she can receive if her body will match current models of "womanliness."

In his art Libera demonstrates how the construction of gender difference is imposed by a culture in which women and men appear to be insufficiently differentiated. As a result, this difference needs to be underlined, overwrought. Women should adapt to the contemporary model of ideal beauty - by adorning their body, incessantly controlling its state, and by removing any of "manliness" (for instance, the removal of body hair, an act referred to in the work Możesz ogolić dzidziusia / Shave Your Baby, 1996). Men, on the other hand, should eliminate from their appearance all sign of "femininity," strive to achieve the ideal strong, muscular body (Body Master dla dzieci od lat pięciu / Body Master for Children Under Age 5, 1995), while ht most important element in this body becomes the equivalent of the power-denoting, Lacanian Phallus, i.e. the penis (Universal Penis Expander, 1995). Gender difference and the body itself appear to be culturally constructed. Strictly related to this, of course, is the problem of a market that renders available an entire range of products connected precisely with underlining that difference, which is something Libera accents in his works. He focuses on toys that seem innocent but convey to us knowledge of the world and are essential to our socialization. The artist points to a hidden kind of violence embodied in popular toys like Barbie dolls or Lego blocks. He reveals the mechanisms by which toys accustom us to violence, and points out the messages contained within them pertaining to the stereotypical division of gender roles. In Eroica (1997) Libera also points out the erotic dimension of games played by children.

Zbigniew Libera, Positives, photo: courtesy of the Raster Gallery

Zbigniew Libera, Positives, photo: courtesy of the Raster GalleryIn one of his newest works titled Pozytywy / Positives (2004), the artist references our memory and the manner in which it is affected by images of war, catastrophes, human tragedies. Libera has here used the multiple meanings of terms related to photographic technique: negatives and positives. If there is a negative image - a dark image, in a symbolic sense: one that is terrifying in its expression, then there must also be its analogue - a color positive, that in a symbolic sense is joyful and carefree. For this series the artist selected famous photographs documenting the horror of war, destruction, carnage. We have seen most of these images elsewhere, in the pages of history textbooks, in newspapers, in World Press Photo exhibitions. In restaging these images to closely resemble the original, the artist introduced subtle modifications to render the images he created positive in their expression. In the photograph referencing an image from a World War II era concentration camp, the "Mieszkańcy" / "Inhabitants" smile, are generally joyful and content. As in the original, they wear the striped prisoner uniforms, but these are pajama stripes. Barbed wire has been replaced with rope, yet the sinister dimension of the original is not entirely eradicated, for we are unable to forget the "negatives" in our minds. The laughing, nude girl in the photograph titled Nepal evokes the terrified child from the photograph known as Napalm. The image of tragedy emerges from behind that figure - though it emerges solely in our imagination - becomes its inseparable shadow. Libera demonstrates something relatively surprising: we have in some sense become accustomed to images of tragedies and catastrophes. The Positives series encourage us to reconsider their ominous meaning. Libera's works tell us of the seductive power of images: even of the darkest, most evil images, or perhaps above all of those. These works are about use, exploitation. Images of death and catastrophes become visually attractive material, because their drastic nature proves capable of drawing our attention. What results here is a kind of visual cannibalism. This art seeks to unmask the mass media and its excessive concentration on images of the bedraggled body.

Art after 2000

Julita Wójcik, Peeling potatoes performance, the Zachęta Gallery, 2001, photo: Jacek Niegoda

Julita Wójcik, Peeling potatoes performance, the Zachęta Gallery, 2001, photo: Jacek NiegodaPolish art soon after the year 2000 manifested a turn toward the iconosphere of popular culture. An entire range of artists (including Zbigniew Libera, Mariola Przyjemska, Joanna Rajkowska, Anna Baumgart, Robert Rumas) immersed themselves in the issue of this culture. New phenomena, consisting of light, pleasant and banal art, also appeared on the art scene around the year 2000. Primarily, this consisted of the paintings, referencing the popular iconosphere, of artist members of the no longer existent group Ładnie [Prettily], artists like Rafał Bujnowski and Marcin Maciejowski. The artists employ the same methods as those used in popular culture, commenting on reality, indicating the changes occurring within it. There were also those who initiated activities directing viewers' attention toward the ephemeral, exploiting the problem of events occurring (I have in mind the activities of Cezary Bodzianowski and Paweł Althamer, whose art exceeds the phenomena under discussion, which is why they are not covered in this discussion).

Art began increasingly to simulate popular culture, changing in terms of its form, (with younger artists more willingly employing painting as their chosen means), and in terms of the weight of the problems it explored (reflected in such terms as "new banality" or "pop banal," used in reference to the works of the Ładnie [Prettily] group). Lines were blurred between art and consumer culture, art surrendered entirely to the stylistics of popular culture, was seduced by its charming poetic. The impression is generated that there was a complete appropriation of art by pop culture. However, these artists proceeded to analyze the language (visual) that affects our perception of the world and the relations transpiring within it. They turned their attention toward collective imagination shaped by the contemporary visual sphere: movies, ads, television news, advertising leaflets. It might seem as if these paintings neither conceal nor reveal anything. And yet they shift focus to seemingly insignificant and unessential elements of pop culture's visual language. They demonstrate how the structures of this language produce our common (incoherent) image of reality, how the communiqués appearing in this sphere shape our imagination. Artwork that references pop culture aesthetics, ads, illustrated magazines, emphatically demonstrates how this sphere shapes both our reality and our perceptions thereof.

The critical blade was also dulled in art referencing feminism. The change that occurred there could be described as a shift to a post-feminist position. The art of Julita Wójcik (b. 1971) seems most characteristic here. It incorporates the everyday that is positioned culturally as the opposite extreme of high art. Weeding the garden, knitting, peeling potatoes or onions are the subjects of the artist's actions. Wojcik plays with the stereotypical perception of femininity womanhood: for it was the task of women to "beautify" reality, which the artist does by, for example, panting flowers in some urban space of her choosing. All these typically female activities are used and transformed into what is amusing, pleasant and carefree. It is the kind of play of a young girl who does subversive things: like a true homemaker she peels potatoes (2001), and additionally does so in an exhibition space of the Zachęta National Modern Art Gallery. This action, apart from the irony embodied in it, acquired a critical dimension, even a feminist one. For it can be linked with the issue of the transgressing nature of the woman-artist, who as late as the 19th century, in order to become an artist, ad to deny the definition of "femininity," for creativity was the domain of men.

Elements of irony are also present in the work of Elżbieta Jabłońska (b. 1970), who during her openings prepares exquisite feasts, acts as a server, serves her guests. The artist plays with stereotypes according to which a woman should above all feed others (as a mother, wife, hostess, housewife) while having to watch her weight. This is a sarcastic commentary to the communiqués which women receive popular culture. In the work Gry domowe / Indoor Games (2002) the artist dons a Superman costume to become "Supermom", sitting with her son Antek on her lap in the middle of her realm - the kitchen. Although in a Superman costume, Jabłońska and her son adopt the pose of the Madonna and Child, sarcastically indicating how many contradictory threads of identification are imposed on expectations relative to mothers.

These artists' stances burst with ambiguities. Their works can be identified as third-wave, sarcastic feminism.

Toward History

Piotr Uklański, The Nazis, 2000 and Dance Floor 1996, installations view, Courtesy of the Zacheta Gallery

Piotr Uklański, The Nazis, 2000 and Dance Floor 1996, installations view, Courtesy of the Zacheta GalleryInterest in history, increasingly present in art after the year 2000, seems to be that which opposes the banal. This interest is often accompanied by exploration into how history is co-created by popular culture, how this culture impacts how we think about history (as demonstrated already in Libera's work titled Lego. Obóz koncentracyjny / Lego - Concentration Camp). We can speak of interest in issues of the second world war, the Holocaust (including Artur Żmijewski's previously mentioned works); Polish-German relations (e.g. Wspomnienia z miasta L. / Memories from the City of L., Monika Kowalska, Grzegorz Kowalski, Zbigniew Sejwa, 2004) and Polish-Jewish relations, but also noticeable was an appearance of interest in modern history: sometimes of the Polish People's Republic, social revolts aimed at achieving freedom. This interest in historical facts seems incidental to questions about history itself, about how it is constructed, used, employed; history also mixes with fiction; how it operates in our imagination.

A relatively strong contrast can be noticed between this art and that which dominated the Polish art scene in the 1990s (excluding Libera's Lego - Concentration Camp, which clearly presaged these interests). Critical art focused on exploring the entanglement of the individual, on corporal experience, on the issue of the Other or omnipresent power (as understood by Michel Foucault). At the turn of the 1990s and 2000s one could have had the impression that this art lost its radical edge, that its critical blade was clearly dulled. Artists like Zbigniew Libera, Artur Żmijewski or Katarzyna Kozyra did not cease to experiment, and exploration of reality continued to appear in their art and in the simulations it incorporated. They abandoned analyzing the situation of the individual subject (and his/her individual problems like illness, disability, gender-related issues) in favor of more general exploration related to the issues of imagination (Libera's Pozytywy / Positives), dreams (Kozyra's Kiedy marzenia stają się rzeczywistością / When Dreams Become Reality), memory and national identity (including Artur Żmijewski's Nasz śpiewnik / Our Songbook). We might of course consider if contemporary art is a break with the stances of the 1990s or if it constitutes their continuation? If in the 1990s we had to deal with analysis of the situation of the Other (a sick, terminally ill or disabled person), then now we can also speak of the exploitation of the issues of Otherness, but clearly in the plural (e.g. Jews, Germans). Artists have turned their attention toward collective concepts (collective imagination and memory), and began to appear question about what is shared, about memory, history, its structuring and its contemporary significance.

One of the problems that art poses relates to the question regarding the extent to which history is also constructed by popular culture, the extent to which fiction mixes with reality and the extent to which history itself becomes simulation. This problem was broached directly by Piotr Uklański (b. 1968) in is exhibition titled Naziści / The Nazis (2000), presented at the Zacheta Gallery. The artist collected film stills of Nazis as presented in various feature films. These stills were portraits of a kind. By focusing attention on images the artist effectively demonstrates to us their power. The Nazis as known from popular culture images are strong men, handsome, possessing clear, regular facial features. Their images have an unusual power, they seduce us and draw our gaze. They simultaneously reproduce the discourse of strength and power. If we were born after the war, if we do not look through archival war images, we do not in fact know what real Nazis looked like. Or rather, we do know, but this knowledge is something we garner above all from popular culture. It is from it that emerges the image of the Nazi as we commonly perceive him - the criminal, beast, emotionless human, demented, while simultaneously, in a visual sense, a handsome and seductive man. In selecting these images, Uklanski wised to force viewers to think about the extent to which popular culture repeats certain clichés, for instance those about a strong and healthy body - clichés which the III Reich also propagated.

Zbigniew Libera's and Dariusz Foks' Co robi łączniczka / What a Courier Does (2005/6) explored a similar problem - the blending of truth and fiction, the influence of popular culture on history. The exhibition was accompanied by a booklet consisting of sixty-three chapters of poetic prose and of photographs selected and transformed by Libera. Into the scenery of the Warsaw Uprising, the artists inserted photos of film stars, beautiful actresses of past years. This work juxtaposed the tragic nature of war with the beauty of the actresses in their alluring poses. This work also touches upon the problem of history and how it is shaped, the exploitation of history by ideology, instead of posing questions about historical truth. In addition, the story of World War II, of the Warsaw Uprising, is something we know less from documents and more from their fictionalized versions. Thus, the project above all asks about what we believe in, or also why let ourselves be seduced? Libera has stated that the work is about permeation. He speaks of blending images and contexts that seemingly do not match, but of a kind of blending that is already encoded in our imagination. What remains within it are traces of images and films about wars, where tragedy blends with eroticism, and death blends with sex. As a work, Co robi łączniczka / What a Courier Does is primarily about "seduction" and about the dissolution of the boundaries between reality (history) and fiction (culture).

Given this flight into fiction and simulation, given the distortion of our imagination, in their search for truth artists began asking about the place, or more precisely about the memory inked to given places, about the "scars of history" and about the "ghosts of the past".

Mirosław Bałka, Bambi, 2003, still from video-installation, Winterreise

Mirosław Bałka, Bambi, 2003, still from video-installation, WinterreiseThis art attempts to settle accounts with history while simultaneously tackling the problem of "how to create art after the Holocaust". This is the subject of, among others, the art of Mirosław Bałka. In the video Winterreise (2003) the artist poses questions about the place memory and the meaning of traces of the Holocaust. The work consists of three films: Staw / Pond, Bambi 1 and Bambi 2, which Bałka shot during a winter excursion to Brzezinka / Birkenau. The films depict the pond into which the ashes of cremated Holocaust victims were discarded, and deer wandering in the vicinity, approaching the barbed wire fence surrounding the camp. The opening at the Starmach Gallery featured a performance in the courtyard of Schubert's songs from the "Winterreise" series which explore man's solitude. Bałka has stated that he wanted to juxtapose these worlds, explore the meaning the human individual relative to the experience of the Holocaust. Through this film Bałka talks about the Holocaust indirectly, evoking merely a fragment of the landscape of a former concentration camp. What we see primarily are images of nature. It is worth citing Frank Ankersmit here from his essay "Remembering the Holocaust: Mourning and Melancholy." The historian cites the Dutch poet Armando, who presented the Holocaust not by referring to the crimes committed in the camps, but by blaming the landscape, the trees surrounding the KZs and the land, which were witnesses of the cruelty and which in and of themselves in a certain way became partners in the crime. One might ask if Balka also faults the landscape, nature, the deer that approach the barbed wire fence. Rather, he seems to demonstrate the "unmoving" nature of the landscape relative to the traces of the crime it bears (the pond and fence). Just as with Ankersmit's proposed interpretation of Armand's poetry, what we have here is indication combined with metonymy that is the opposite of metaphor:

Metonymy favors ordinary closeness, respecting all the unforeseeable accidents of our memory and as such is a decisive opposite of proud, metaphorical appropriation of reality.7

Elżbieta Janicka's works from the Miejsce nieparzyste / Odd Places series are also about the impossibility of representing the Holocaust (2006). These photographs (their status as such is indicated by frames evoking the perforation of photographic films with the photo number, ISO number, etc.) are captioned with the names of paces that were the site of extermination camps. Yet these images are empty, white, ones upon which we find nothing represented, for Janicka photographed the air above what were once extermination camps. Memory of place, in turn, is explored by Rafał Jakubowicz in his project Pływalnia / Swimming Pool (4.04.2003, Poznań). This consisted of a projection on the facade of a former synagogue in Poznań, which the Nazis converted into an indoor swimming pool and which remains a pool to this day. The projection consisted of the Hebrew word meaning "swimming pool." At their core, these works most strongly seem to be about absence, about the deletion of dramatic facts from our imagination. This art points to what has been repressed and forgotten, and psychoanalytic theories contend that repression shapes our personality, character, affects the manner in which we handle current problems. Uncured trauma casts its shadow over our entire life. And it is for this reason that this art becomes a kind of therapy.

Against this background of historical disputes, art is an important voice in the discussion regarding the nature of history. It observes our reality and history from altogether different perspectives, offering a way of working through trauma, even of scratching open the wounds of history and thus initiating a kind of therapy. This view of history that appears in art, differing entirely from that of the dominant political discourses, might also contribute to engendering a different view of history inclined toward understanding, co-sensibility, joint suffering. And it is this inclination toward broadening the potential of emotion, increasing sensitivity through art, revealing what is concealed, is exactly what links art that exploits the issue of history with the critical art that preceded it.

Author: Izabela Kowalczyk, November 2006.

Notes:

1. "Wytrącić z automatyzmu myślenia" ["Disrupting Automatic Modes of Thinking"] (An interview with Professor Piotr Piotrowski by Maciej Mazurek), [in:] "Znak," December (12) 1998, pp. 146-160.

2. Cf. Ryszard W. Kluszczyński, "Artyści pod pręgierz, krytycy sztuki do kliniki psychiatrycznej, czyli najnowsze dyskusje wokół sztuki krytycznej w Polsce" ["Artists to the Stocks, Art Critics to the Psychiatry Clinic, or Recent Discussions or Critical Art in Poland"], [in:] "EXIT. Nowa sztuka w Polsce," no. 4 (40), 1999, pp. 2074-2081.

3. After Zygmunt Bauman, "O znaczeniu sztuki i sztuce znaczenia" ["On the Significance of Art and the Art of Signifying"], in: "Awangarda w perspektywie postmodernizmu" ["The Avant-Garde from a Postmodern Perspective"], ed. Grzegorz Dziamski, Poznań, 1996, p. 137.

4. Krzysztof Pomian, "Sztuka nowoczesna i demokracja" ["Modern Art and Democracy"], manuscript provided by the author, published in: "Kultura współczesna," no. 2 (40), 2004, pp. 35-43.

5. Michel Foucault, "Nadzorować i karać. Narodziny więzienia" ["Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison"], trans. T. Komendant (Warszawa: Aletheia Foundation, 1998).

6. John Berger, "Ways of Seeing" (London: 1972); John Berger, "Sposoby widzenia", trans. M. Bryl, (Poznan: Dom Wydawniczy REBIS, 1997).

7. Frank Ankersmit, "Pamięć Holocaustu: żałoba i melancholia / Remembering the Holocaust: Mourning and Melancholy, [in:] "Narracja, reprezentacja, doświadczenie. Studia z teorii historiografii [Narration, Representation, Experience - Studies in the Theory of Historiography"], ed. Ewa Domańska (Kraków: Universitas, 2004), p. 406.

For more on critical art by the same author see her two books: "Ciało i władza. Polska sztuka krytyczna lat 90." ["The Body and Power - Polish Critical Art of the 1990s"], (Warsaw: Sic!, 2002) and "Niebezpieczne związki sztuki z ciałem" ["The Dangerous Liaisons of Art and the Body"], (Poznań: Galeria Miejska Arsenał, 2002).