Isaac Bashevis Singer once compared him to a hybrid of Proust and Kafka. Bruno Schulz stands out today – over seven decades after his death in the Drohobycz ghetto – as a particularly singular artistic figure. Having inspired writers like Danilo Kis, Cynthia Ozick and Jonathan Safran Foer, as well as filmmakers like the Quay brothers and Guy Maddin, it seems obvious that Schulz’s art will live on through hundreds of adaptations on film or on paper.

A contemporary of Gombrowicz and Witkacy, terse Schulz published only two diminutive volumes of prose during his lifetime. The Street of Crocodiles (published in 1934 under the title Cinnamon Shops) and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937) received mixed reactions from Polish critics. Throughout the whole interwar period, Schulz remained a marginal figure in Polish literature and arts. His outstanding series of disturbing drawings meant as illustrations for Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs was published many years after his death as The Book of Idolatry. The novel he is rumored to have been completing at the time of his death, the surprisingly influential work The Messiah, may actually never have existed at all. The manuscript of the novel hasn't been seen since World War Two and was probably unfinished.

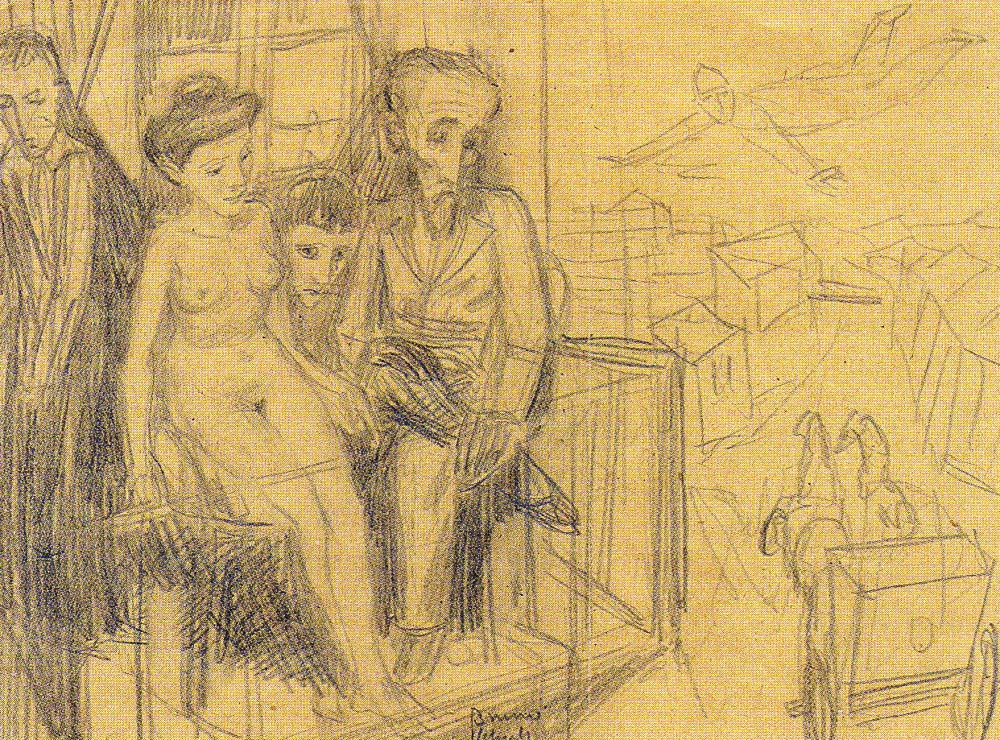

Spotkanie (The Meeting) - the only surviving oil painting by Bruno Schulz

Spotkanie (The Meeting) - the only surviving oil painting by Bruno SchulzAnimating Schulz

The Quay Brothers came across Schulz and the Polish writer rapidly became one of their most prominent literary influences . Their Street of Crocodiles is an early example of the brothers' long-lasting interest in Polish culture.

It is the first film the brothers shot using 35mm tape. Rather than being a faithful adaptation of one single story, it mixes several Schulzian motifs from while introducing different ideas of their own. Terry Gilliam considered this film one of the ten best animations in the world. And Schulz – along with Kafka, Robert Walser and Felisberto Hernández – remained one of the brothers' main sources of inspiration. For some time, there has been talk of a Quays Brothers feature based on Schulz's other book Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, which was adapted by Wojciech Jerzy Has over 40 years ago.

Adapting the sanatorium

Still frame from J.W. Has's Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hour-glass. Pictured: Jan Nowicki, photo: Polfilm / East News

Still frame from J.W. Has's Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hour-glass. Pictured: Jan Nowicki, photo: Polfilm / East NewsAlong with his

Manuscript Found in Saragossa, the

Hourglass Sanatorium by

Jerzy Wojciech Has is among the most famous Polish films ever made. Sanatorium is also considered one of the most successful adaptations of a literary work – Has found a way to render Schulz’s poetic prose into the language of film. Like in the Quay brothers' film, Sanatorium blends several stories by Schulz centered around a father and son traveling down the dead alley of time. The film won the Jury Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival.

Writers in search of The Messiah

In terms of books that no one has ever read, or even seen, The Messiah is probably a strong contender for most popular. Meant to be Schulz’s magnum opus, he had reputedly been working on it on and off since 1934. The manuscript – along with countless illustrations – disappeared during the war. Jerzy Ficowski, an indefatiguable Schulz scholar and discoverer of many lost manuscripts, believed The Messiah would eventually surface – possibly in some Russian archive. In the 1990s, Ficowski was approached by a Swedish diplomat who told him about a Russian contact – someone who thought he saw several Schulz's manuscripts in a KGB file. However the diplomat died soon after...

A drawing entitled The Messiah Over A Town (Mesjasz nad miasteczkiem). Could this have been an illustration for the lost novel?

A drawing entitled The Messiah Over A Town (Mesjasz nad miasteczkiem). Could this have been an illustration for the lost novel?Schulz's legendary Messiah has become an inspration for several novels, one of them being Philip Roth's The Prague Orgy. This short novella published for the first time in 1985 had Roth's alter ego Nathan Zuckerman go to Communist Prague in order to seek out the unpublished manuscript of a martyred Jewish writer, Sisovsky. Although Sissovsky wrote in Yiddish, his character clearly resembles Schulz, a shy high-school teacher killed by a Gestapo officer. In the depiction of his death, Roth includes the unmistakable line: ‘He shot my Jew; so I shot his’, a reference to the circumstances of Schulz's death.

Two years after The Prague Orgy, another American writer, Cynthia Ozick, took up the same Schulzian motif. In The Messiah of Stockholm, we follow a Swedish book critic, and a refugee from war-torn Poland who claims to be the son of the Polish genius Bruno Schulz. He is obsessed with his father's legacy, most notably the lost manuscript of The Messiah

Schulz appears also in yet another novel written in the 1980s. In See Under: Love by the Israeli author David Grossman, we follow a young boy called Momik, the son of Holocaust survivors, who later in life starts to believe he is the vessel for new prose by Bruno Schulz.

Bruno Schulz and his books appear also in Roberto Bolaño's Distant Star and Salman Rushdie's The Moor’s Last Sigh.

Dead Class

In Poland, Schulz made his way into theatre through Tadeusz Kantor. The Dead Class from 1975 is considered one of the most important plays made in Poland after WW2 was inspired by the story Emeryt. It includes characters taken from Schulz, like the servant girl Adela.

One of the most successful plays inspired by Bruno Schulz was the 1992 experimental production by Theatre de Complicite. The piece conceived and directed by Simon McBurney was based on The Street of Crocodiles – it included a highly complex interweaving of image, movement, text, puppetry, object manipulation, as well as both naturalistic and stylised performance, all underscored by music from Alfred Schnittke and Vladimir Martynov.

Die cutting Schulz

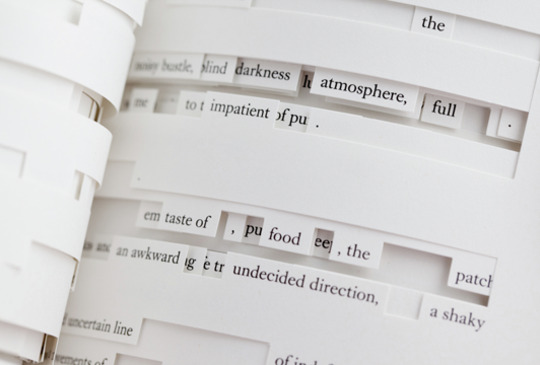

Jonathan Safran Foer's The Tree of Codes

Jonathan Safran Foer's The Tree of CodesThe Street of Crocodiles also inspired one of the strangest books of our times – or is it rather an art object? Making The Tree of Codes (2010), Jonathan Safran Foer used an existing excerpt of Bruno Schulz's book – a text he considers his 'favourite book of all time' – and literally cut out the majority of the words (you can follow this method in the transformation of the title) . He carved out a completely different narrative from what was left of Schulz's text. Here, he describes the idea behind his concept and his appreciation for the original:

If you were going to eat a food you love would you prefer that the plate be overflowing with it rather than there would be a tiny little piece in the center. I would. And his book is overflowing with things that I love.

And in fact the reading material in The Tree of Codes is scanty.

Inside the head of Bruno Schulz

Cover for the English edition of Biller's novel

Cover for the English edition of Biller's novel In the 2013 German fantastical novella Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz, writer Maxim Biller has Schulz meet Thomas Mann in a pre-war Drohobycz – or perhaps only his Doppelgänger. In Biller's book, Schulz talks about this strange visit in a letter to the great German writer. Biller draws heavily on Schulz's illustrations – for him the sadomasochistic imagery found in Schulz's graphic output may be seen as a sign of the fiasco of the assimilation policy, pointing to the real relationship with the dominant culture, with Thomas Mann as a symbol of the dominant Kulturnation.

Schulz did indeed write letters to the German writer, whose book Joseph and His Brothers he had very much admired. Those letters, like The Messiah, remain lost – they may still be at the Thomas Mann Archive in Zürich.

Schulz in voice bubbles

Cover of Woynarowski's Dead Season

Cover of Woynarowski's Dead SeasonThe difficult, lush, almost baroque style of Bruno Schulz has also inspired comic book authors. One of the first to pull Schulz into that medium was German author Dieter Jüdt, who in 1995 adapted one of Schulz's short stories Heimsuchung. One of the most recent attempts, and quite different for that sake, came from the Polish visual artist Jakub Woynarowski. In his experimental Dead Season (2014), the artist took excerpts from twelve works by Schulz but, as noted by comic book critic Łukasz Chmielewski, he refrained from illustrating Schulz's prose. Instead he used the excerpts 'to construct his own story about decay, evanescence, and a closed, looped cycle of life and death, as well as the loneliness of an individual facing cardinal and inevitable processes.' The book, closer to a graphic novel than a comic book, caused much stir among Schulz afficionados, gleaning mixed opinions on the comic book scene.

The Sanatorium under the Klezmer Sign

And how about Schulz in music? While it is one thing for a writer to be adapted in written form (and much of modern cinema draws from literature), Schulz is one of the very few authors to have inspired contemporary musicians, like The Cracow Klezmer Band with music by John Zorn.

Author: Mikołaj Gliński, 19 November 2013, ed. 11/2016