Białystok and the surrounding region has a fascinating cultural history. It’s easy to see how its complicated ethnic relations impacted Ludwik Zamenhof’s family and pushed him towards the idea of an international language. Unlike a multitude of other artificial languages proposed across the 19th and early 20th century, Esperanto stemmed from first-hand experience of the cultural, linguistic and ethnic reality of human diversity. This reality was hardly imaginable in any other European location.

The Tower of Białystok

A family legend, propagated by Zamenhof himself, links the earliest glimpses of the concept of Esperanto with the complex linguistic and ethnic relations of his hometown. As the story goes, the 10-year-old Ludwik wrote a drama entitled The Tower of Babel, or a Białystok Tragedy in Five Acts. In the precocious boy’s story, the biblical tower materialised in the form of Białystok’s town hall, while the square around it, bustling with different languages and dialects, became an illustration of the biblical story about the confusion of tongues.

Seen from this perspective, Białystok may just seem a typical fixture of the multicultural landscape of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with its eastern provinces and towns inhabited by people of many different ethnicities. And yet, the history of the town offers many surprising elements.

Borderland Białystok

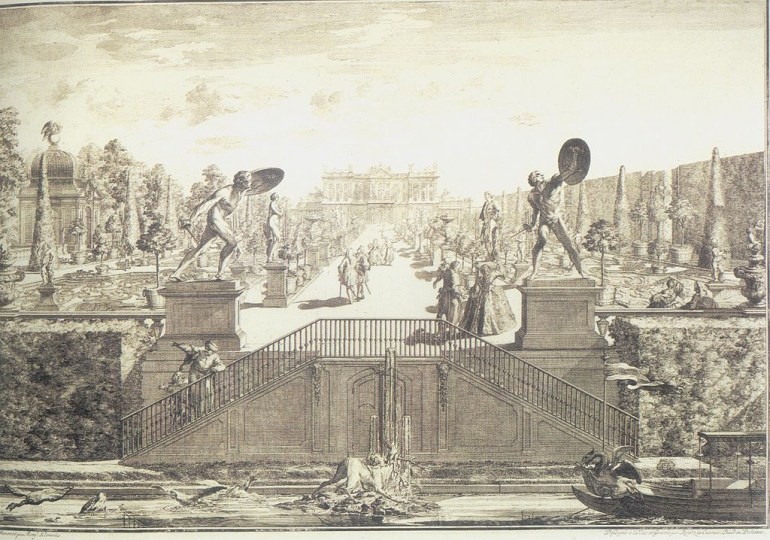

Palace of the Branicki family was for many centuries the central venue of Białystok; art by Pierre Ricaud de Tirregaille; Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Palace of the Branicki family was for many centuries the central venue of Białystok; art by Pierre Ricaud de Tirregaille; Photo: Wikimedia CommonsLudwik Lejzer Zamenhof was born in Białystok into a Jewish family with strong Russian cultural ties. His father had a bureaucratic post in the Russian administration as a censor of Hebrew books, but it was his other profession, as a language teacher, that came with a fascination he was able to pass on to his son.

Before Ludwik’s birth in 1859, the family had lived in Białystok for only two years. Prior to that, his parents lived in Tykocin, and before then in Suwałki, where Ludwik’s father Mordekhai (Marek) was born in 1837, which remains the earliest attested place of origin for the Zamenhof family.

When Ludwik was born, Białystok was a town of close to 14,000 people incorporating many cultures, languages and religions. The 1857 census shows that Białystok’s population was 69% Jewish, 22% Catholic (mostly Poles), 5% Protestant (Germans) and 4% Orthodox (Russians).

This ethnic composition reflected two things. On the one hand it showed the earlier, borderland character of the town and region, inhabited by diverse local ethnicities, like Ruthenians (Belarusians), Mazovians (Poles), but also Tatars. On the other, it reflected some newer developments typical of the modern era, like the settlement of Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a process particularly intense in the state’s eastern provinces following the expulsion of Jews from Western Europe in the late 15th century.

Last but not least, the 19th-century demographics of Białystok were rooted in the recent historical developments connected to the so-called Partitions of Poland. In the late 18th century, the partitions had erased Poland from the map of Europe, effectively putting Białystok under foreign administration.

Meanwhile, in Prussia...

This can be seen in the 5% German component in the ethnic make-up of the town which can be particularly interesting and revealing, as it points towards an often downplayed chapter in the history of the town and the whole region.

Following the third partition of Poland in 1795, the area was incorporated into Prussia, with Białystok becoming the capital of the New East Prussia province. This period, though admittedly short (it lasted only 12 years), had not only left a mark on the ethnic composition of the town, but it also literally inscribed itself into the history of the Zamenhof family.

According to new research by Zbigniew Romaniuk, it was precisely around this time between 1803-1807 that one of Ludwik’s ancestors, Wolf (Zeev), was officially given the last name Zamenhof. This was part of the administrative procedure undertaken by the Prussian authorities in regard to Jews in a region where they had rarely ever used surnames. Romaniuk suggests that the original form of the surname Samenhof should be linked with rural origins of the Zamenhofs (the German word Samen means ‘seed’), who probably at this time traded grain for living.

German settlement in Białystok continued after the Napoleonic wars, and was also crucial for the development of the textile industry for which the town would soon become famous. In the late 19th century, Białystok was to become the third biggest centre for textile production in Europe (after Moscow and Łódź), earning the title of the 'Manchester of the North' (that would be Eastern North). This partly explains why both Marek and Ludwik knew German very well – Ludwik considered it one of the three languages he felt comfortable speaking.

Meanwhile, in Russia...

Ulica Zielona, the street in Białystok where Zamenhof was born, renamed in his honour after his death, 1918-1927; Source: NAC

Ulica Zielona, the street in Białystok where Zamenhof was born, renamed in his honour after his death, 1918-1927; Source: NACIn 1807, following the treaty of Tilsit, Białystok was incorporated into the Russian Empire. This triggered a massive inflow of new Orthodox inhabitants into the town. While Russian was now the official language of administration, German remained popular among the industrialists. Meanwhile, the folk in the streets of Białystok stuck to Yiddish and Polish.

This Babel-like town became the backdrop of Zamenhof’s early life. It was here that he attended the prestigious Białystok middle school where he began to learn Russian, the language that would go on to become his most beloved. In the future, he would even often identify as a Russian Jew, although this is admittedly a complicated issue.

It was also here in Białystok while still in school that he developed an early version of his international language, a draft of which was reportedly destroyed by his father.

Poland returns

International Congress of Esperanto, Białystok 1927, present on the photograph, among others, are: Feliks Zamenhof, Lidia Zamenhof, Pál Balkányi, Helmi Dresen, Teo Jung; Photo: Wikipedia

International Congress of Esperanto, Białystok 1927, present on the photograph, among others, are: Feliks Zamenhof, Lidia Zamenhof, Pál Balkányi, Helmi Dresen, Teo Jung; Photo: WikipediaAs it turned out, it would be another fifteen years before the first Esperanto handbook appeared in print. This happened in 1887 in the much different urban environment of Warsaw, the city where Zamenhof would eventually spend the majority of his life and where he died in April 1917. The partitions crumbled with the end of World War I just a year and a half later, and Poland, the place Zamenhof had spent virtually his whole life, appeared back on the political map of Europe, with his hometown Białystok within its borders. Of course, the multicultural Białystok from his youth would cease to exist some twenty years later with the advent of World War II and the Holocaust.

Still, it was the everyday reality of an Eastern European town lost in a borderland Babel-like area of mixed cultures, languages and religions that was the key inspiration behind the idea of an international language, an idea that is still trending and inspiring people today.

Author: Mikołaj Gliński, 14 April 2017