Grotowski made his directorial debut in 1958, with the 'Gods of Rain' production. In this performance he introduced his bold approach to text. Later in 1958, on the invitation of theatre critic and playwright Ludwik Flaszen, Grotowski moved to Opole where he became director of the Theatre of 13 Rows.

There he began to assemble a company of actors and artistic collaborators which would help him realize his unique vision. It was also there that he began to experiment with approaches to performance training which enabled him to shape the young actors initially allocated to his provincial theatre into the transformational artists they eventually became.

Curiously similar to Kantor’s choice, one of the early and better known stagings of his first theatre included Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus. The company also staged Shakuntala based on text by Kalidasa, Dziady / Forefathers’ Eve by Adam Mickiewicz, and Acropolis by Stanisław Wyspiański.

Acropolis

Although Grotowski’s name is not strongly associated with Poland's World War II history, the performance which is said to have best presented his concept of the Poor Theatre was an attempt at depicting the most grim of this history’s events. In Acropolis, Grotowski tried to represent the unrepresentable - the nightmare of Auschwitz.

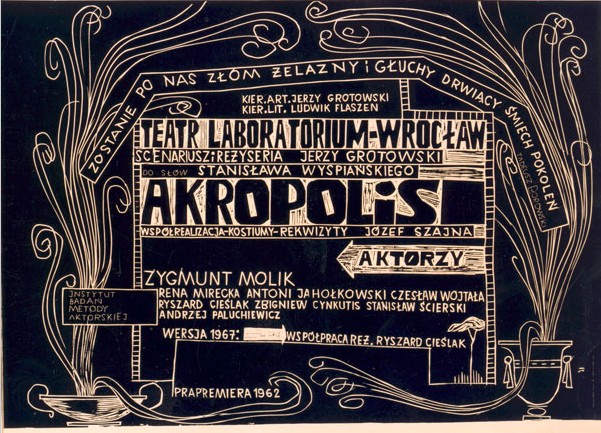

Poster for Akropolis, version V, courtesy of the Grotowski Institute

Poster for Akropolis, version V, courtesy of the Grotowski InstituteFor the production, Grotowski collaborated with legendary director and designer Józef Szajna. Acropolis premiered on the 10th of October 1962 and was based on the dramatised poem published by Stanisław Wyspiański in 1904. Wyspiańki’s work consisted of a prophetic drama which combined motifs from Polish history with Homeric and Biblical sequences, thus staging a summa of Europe’s Mediterranean cultural heritage. As its central theme, however, Acropolis evoked the idea of resurrection, both in the sense of redemption from death and oblivion, and that of a task to be faced by each man.

This axis of the play was moved by Grotowski into a concentration camp - he juxtaposed Europe’s great founding myths with the Holocaust, placing them under radical if not impossible scrutiny. In Grotowski’s vision, the actors built the symbolic space of a crematorium on stage, and their close proximity to the audience served the paradoxical purpose of creating radical distance between them and their viewers. The actors seemed to completely negate the presence of the audience, and the strange, hostile world they evoked is said to have depicted the unimaginable reality of the concentration camp. Acropolis is considered a masterpiece of 20th-century theatre across the world.

The ecstatic acting techniques

In working with the actors, Grotowski paid significant attention to voice resonators. Through various physical exercises and ways of working with the voice, Grotowski attempted to tap into the sources of ancient expression. Fascinated with the thoughts of Carl Jung, he sought out archetypes that would prove helpful in building roles and turn his actors' efforts into an act of sacrifice. The ecstatic acting techniques of the Laboratory Theatre were not aimed at achieving a state of trance, but rather on nurturing precise acting in a state of sharpened consciousness. The Constant Prince and Apocalypsis Cum Figuris were apogees of ecstatic acting, and also exemplified the concept of "poor theatre," about which Peter Brook wrote in The Empty Space, published around the same time–

In Poland there is a small company lead by a visionary, Jerzy Grotowski, that also has a sacred aim. The theatre, he believes, cannot be an end in itself; like dancing or music in certain dervish orders, the theatre is a vehicle, a means for self-study, a means for self-study, self-exploration, a possibility of salvation. The actor has himself as his field of work. [...] Seen this way, acting is a life's work - the actor is step-by-step extending his knowledge of himself through the painful, ever-changing circumstances of rehearsal and the tremendous punctuation points of performance. [...] Grotowski makes poverty an ideal; his actors have given up everything except their own bodies; they have the human instrument and limitless time - no wonder they feel the richest theatre in the world

Theatre of Sources

In the 1970s Jerzy Grotowski slowly began to abandon theatre and ceased staging productions entirely. He deepened his studies into Central Asian culture and schools of spirituality. In 1970 he took his third trip to the East, travelling to India. (Earlier, he had voyaged to Central Asia in 1956 and visited China in 1962.) He also travelled to Mexico, Haiti and elsewhere, searching for elements of technique in traditional ritual practices that could have a discernible effect on participants. One of the key collaborators in this phase of work include Włodzimierz Staniewski, subsequently founder of Gardzienice Theatre.

Grotowski made use of his international ties, and his relative freedom to travel allowed him to pursue this programme of cultural research in order to flee Poland following the imposition of martial law. He spent time in Haiti and in Rome, where he delivered a series of important lectures on the topic of theatre anthropology at the University of Rome La Sapienza in 1982 before seeking political asylum in the United States. His friends Andre and Mercedes Gregory helped Grotowski to settle in the US, where he taught at Columbia University for one year while attempting to find support for a new programme of research.

Paratheatre

The Paratheatrical phase of Grotowski’s work, an evolution of his search towards purity of encounter, lasted from 1973 till 1978. It was opened with the publication of Grotowski’s text titled Holiday, which outlined this new course. This period constituted an attempt to transcend the separation between performer and spectator. This division was to vanish in the new training/performance projects the artist began organizing in 1973. In the model of culture postulated by Grotowski, no one was a consumer, while everyone had the right to create. Subsequent endeavours, referred to as projects, were publicized and open to all those willing to participate. Participants from throughout the world travelled to Wrocław and to Brzezinka, near Oleśnica, where the projects were held. The actions sometimes went on for extended periods, and at times had the participants find themselves in barren natural environments, attempting to provoke in them a deconditioning of impulse. A telling account of the experience from the perspective of American theatre artist, Andre Gregory, is spoken about in the context of its time and American society in the film My Dinner with Andre, starring Gregory and Wallace Shawn.

Later on, Grotowski clarified that he quickly found this direction of research limiting, having realized that unstructured work frequently elicits banalities and cultural clichés from participants.

Objective Drama

The funding for further work in Manhattan was not obtained, and in 1983 Grotowski was invited to UC Irvine, where he began a course of work known as 'Objective Drama'. This phase was an investigation of the psychophysiological impact of selected songs and other performative elements derived from traditional cultures. It focused specifically on relatively simple techniques that could exert a discernible and predictable impact on the doer regardless of their belief structures or culture of origin. Ritual songs and related performative elements linked to Haitian and other African diaspora traditions became an especially fruitful tool of research.

Art as Vehicle

In 1986, Grotowski was invited by Roberto Bacci to shift the base of his work to Pontedera, Italy, where he was offered an opportunity to conduct long-term research on performance without the pressure of having to show results.

Grotowski characterized the focus of his attention in his final phase of research as "art as a vehicle," a term coined by Peter Brook. "It seems to me," Brook said, "that Grotowski is showing us something which existed in the past but has been forgotten over the centuries; that is that one of the vehicles which allows man to have access to another level of perception is to be found in the art of performance."

Although Grotowski died in 1999 after a prolonged illness, the research of Art as Vehicle continues at the Pontedera Workcenter, with Richards as Artistic Director and Biagini as Associate Director. Grotowski's will declared the two his "universal heirs," holders of copyright on the entirety of his textual output and intellectual property.

Konrad Swinarski

Konrad Swinarski

Konrad SwinarskiLived: 1926-1975

Known for: his fascination and collaboration with Bertold Brecht, visionary and innovative use of stage design, avant-gardist approach to text adaptation, providing a blend of the German politically engaged theatre and Polish traditions in the visual and literary arts, as well as inspiring Lupa, Warlikowski, Jarocki, Jarzyna and many more

Similiar to: now evocative of those he had first inspired, Polish theatre directors Lupa and Warlikowski

His life cut short by his abrupt death in a 1975 plane crash, the theatre, television, opera and film director Konrad Swinarski is mentioned here for the fruitful and exceptionally strong impact he had on future generations of theatre makers. Unlike the aforementioned greats of 20th century theatre, he did not leave behind a body of plays, art objects, or methods of working that stretched the boundaries of theatre to later step right out of them. Konrad Swinarski worked in the theatre. What he brought into it was his own unbending vision, led by the idea of what art ought to bring to the human experience.

The director was born in the south-west of Poland, in the region of Silesia. When both of his parents died, he moved to stay with relatives in the city of Katowice. It was there that he took up his artistic education, starting at the PWSSP state higher school of the visual arts. Swinarski then moved to the coast and continued his studies at the Department of Interior Design.

The First Steps: Visual Art and Strzeminski

When Swiniarski moved to continue his studies at the National Art Academy in Łódź, he encountered Władysław Strzemiński, one of Poland’s most famous artists of the early 20th century. Strzemiński was an art theoretician and a pioneer in the Constructivist movement. His Theory of Vision made a big impression on Swinarski, who joined the ST-53 artistic group and exhibited with them. Swinarski completed his studies at the Art Academy in Łódź, and also studied at film school for a brief period of time.

Meeting Bertold Brecht

In 1951, Swinarski took up his studies in Directing at the Warsaw Theatre Academy. There, he was guided by outstanding artists such as Leon Schiller, Bohdan Korzeniewski and Erwin Axer. The fascination that proved crucial to his career was seeing a play by Bertold Brecht, whose group Berliner Ensemble was touring in Warsaw. Swinarski obtained a scholarship and studied at the ensemble, playing the role of assistant to Brecht. After Brecht’s death, together with his other students, he staged Brecht’s Fear and Misery of the Third Reich.

During his period of fascination with Brecht, Swinarski was interested in the simple relationship between a man and the condition of society and the reduction of “good” and “evil” to the categories of wealth and poverty. He was captivated by a theatre that would not so much depict the world as it would try to change it. Swinarski believed the Brechtian aesthetic to be intricately bound with his political thought.

Swinarski worked with many theatre companies in Poland and across the world. He changed his repertoire, as well as the stages he directed on, and continually searched for new means of expression. When he came to judge the Brechtian worldview as dated, Swinarski also broke with his master’s aesthetic. But he continued to believe that artistic means are only there to express the stance that a director or actor has towards reality.

The Matured Style of a New Polish Romantic

Swinarski understood this purpose of theatre in an increasingly deep manner, and he searched for means of expression more apt to his own contemporary reality, and to the context found in Poland.

The developed Swinarski is known to have employed a great variety of solutions and ideas in his stagings. There were purely real elements, such as vegetables and a live hen, there was the naturalistic suggestion of paint meant to look like blood, and then, there were also elements of the fantastic, straight out of the land of fairy tales - with horned devils and winged angels. But Swinarski went further, not so much blurring the boundary between theatre and reality, as introducing reality and life into the theatre. In the words of theatre critic Treugutt, it seemed as if anything was possible:

live doves and dogs, real jumps from the theatre onto a real street, (…) children pretending to be cupid figures, and actors guarding the entrance doors to to the theatre space.

With all elements treated on an equal level, their reality, in effect, began to seem questionable. This how historian and theatre critic Marta Fik describes the way in which a very coherent and, indeed, visionary, world was created by the artist. The domain of doubt was the realm of Swinarski’s theatre, but it was also a doubt that reached to the heights of exaltation, and a passion and desire for knowledge of the world and the human being in it. Marta Fik also wrote:

In all of these performances, life triumphed over fiction. And, strangely enough, it didn’t result in the diminishing of any of the addressed problems. Quite the contrary (…) It also turned out that Romantic heroes who are treated like real figures made of flesh and blood do not lose any of their extraordinary character. But it is no longer a superhuman and ideal kind of nature, but rather one that is very human indeed.

Swinarski has been hailed a true romantic for the knot of contradictions he both impersonated and lived. Much like the romantics, he continually took on the theme of conflict between society and the individual, with echoes of the duality in morality and reality, and the juxtaposition of feelings and politics.

THE CONTINUATORS

Krystian Lupa

Lupa directing Ritter, Dene, Voss, photo: Marek Gradulski

Lupa directing Ritter, Dene, Voss, photo: Marek GradulskiBorn: 1943

Known for: an innovative approach to text, (very long) stagings of the prose by Thomas Bernhard, and authoring his own stage design

Inspired by: Kantor, Swinarski, and… Witkacy

Before turning his attention to theatre, Lupa was briefly a student at the Physics Department of Jagiellonian University in Krakow, and in 1969, he obtained a degree in graphic design. He also spent two years studying directing at the Łódź Film School. In 1973, he took up theatre direction at the State Higher School of Theatre in Kraków.

This path towards the theatre, starting from the visual arts and stopping by at the Film School, resembles that of Swinarski. Curiously enough, Lupa was Swinarski’s student and he has claimed that

the work of Swinarski and Kantor was a psychological event for me. Specifically, I have in mind their stagings of Wyzwolenie / Liberation and Umarła klasa / The Dead Class.

While a student, Lupa attended Swinarski’s classes on play analysis and served as his assistant on the production of Hamlet at the Stary Teatr (Old Theatre) in Krakow. Lupa has admitted that Swinarski taught him to explore the meaning of individual scenes and to work with actors. He was also fascinated by the work of Tadeusz Kantor and his view of the function of the actor. On the other hand, Carl Gustav Jung proved to be the most influential philosopher and thinker to Lupa:

"He is a master of the path - not only of truth - but a master of the path to the truth."

(Krystian Lupa for Notatnik Teatralny (Theatre Notebook), 1993).

Lupa made his professional theatre debut in 1976, with a production of Slawomir Mrozek's Slaughterhouse at the Juliusz Slowacki Theatre in Krakow. He has worked in theatres all over Poland as well as in Germany, Greece and Austria. But he has created some of his most remarkable productions at the Stary Theatre in Krakow. He began his work at this theatre by staging Powrót Odysa / The Return of Odysseus by Stanisław Wyspiański (1981), a play to which he would return in 1999, staging it once more at the Teatr Dramatyczny (Dramatic Theatre) in Warsaw. Lupa also took on Austrian literature for the first time while at this Krakow theatre. In creating his original production titled Miasto snu / City of Sleep (1985), Lupa drew inspiration from Alfred Kubin's novel Po tamtej stronie / The Other Side. Since 1985, he has directed plays based on the works of Alfred Kubin, Robert Musil and Rainer Maria Rilke, Hermann Broch, Werner Schwab and Thomas Bernhard, whose novel Das Kalkwerk he adapted for the stage in 1992.

Auslöschung based on the Thomas Bernhard, directed by Krystian Lupa

Auslöschung based on the Thomas Bernhard, directed by Krystian LupaPerformed at the Narodowy Stary Teatr, Das Kalkwerk ended up touring Europe and making it across the ocean as the first Polish play invited to New York's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts Festival in 2009. Though "Mr. Lupa’s aesthetic is one that will probably prove demanding even to local theatregoers with adventurous tastes" according to the New York Times review, "This is all-bran European theatre, requiring much chewing and devoid of artificial sweetening", his signature production left a strong impression on the American public.

His artistic relationship with Bernhard’s works which started in 1992, has proved to be an enduring one. So far, Lupa has adapted six works by the Austrian provocateur. He has staged the plays Immanuel Kant, Over All the Mountain Tops, Ritter, Dene, Voss, and the novels The Lime Works, Extinction, and Woodcutters. The latter play has also been presented to the Austrian public. A difficult task, as Bernhard’s books are read by Austrians themselves like pamphlets about Austrianness. But the Pole is an authority on Bernhard, and is even a chairman of the Austrian Thomas Bernhard private foundation.

Lupa and Bernhard appear to be a perfect match. Bernhard's writing concerns the human being and its relations with others. His work is influenced by the feeling of being abandoned and shows death as the ultimate essence of existence.

Over a period of more than two decades, Lupa has accustomed his audiences to an aesthetic that breaks all rules as he creates worlds that seems to go on forever, and gradually pull the spectator deeper and deeper inside. The director has also accustomed his followers to abrupt changes in the way he approaches theatre.

In 2008 he received the European Theatre Award the achievements of his career. Previous ETA winners include Harold Pinter, Robert Wilson and Pina Bausch.

Lupa's state of mind is a European one. His plays reflect the exhaustion of the Old Continent and all of its descents into decadence. Being a Pole, a German or an Austrian has no meaning in and of itself. What is important is the spiritual context in which we act and live, rather than any national, historical or political context. (...) European spirituality of the twentieth century is the most essential dimension of activity, the site of real struggle and conflict, a realm of strong tensions.

- Piotr Gruszczynski, Notatnik Teatralny

Lupa also teaches directing at the Ludwik Solski State Drama School in Krakow. His published writings on the theatre include Utopia and Its Inhabitants, along with Labyrinth and Spying, two volumes of his diaries.

Krzysztof Warlikowski

Krzysztof Warlikowski, photo: Agencja Forum

Krzysztof Warlikowski, photo: Agencja ForumBorn: 1962

Known for: revolutionary stage adaptations of contemporary texts, including the prose of J. M. Coetzee, an innovative take on Shakespeare’s drama, operatic productions across all of the Europe’s most significant stages

Inspired by: Swinarski, Lupa

From today’s perspective, it is clearly visible that the most outstanding student of Lupa is Krzysztof Warlikowski. The director earned his position very slowly. His first adaptations met with a cool reception. It was said that they were hermetic, overly aestheticized and unintelligible (incidentally, early adaptations by Lupa received the same critique). Today, Warlikowski is a mature, developed artist, recognized both in Poland and abroad (where he directs more often than in Poland).

After studying history, Romance languages and philosophy at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Warlikowski left for Paris in 1983, where he attended a seminar on Classical theatre at the École Pratique des Hautes Études and studied philosophy and French language and literature at the Sorbonne. In 1989 he returned to Poland and passed the entrance exams for the Theatre Directing Department of the State Higher School of Theatre in Kraków, where he studied under Krystian Lupa. Following his graduation, Warlikowski directed in theatres in Poland, in Kraków, Poznań, Toruń, Radom and Warsaw, and abroad, in Hamburg, Tel Aviv, Milan and Stuttgart. The director began to cooperate with the Teatr Rozmaitości in Warsaw, now known as TR Warszawa, in 1999. He staged seven performances there, and all were successful in Poland and abroad at international festivals. Warlikowski also directed companies in Zagreb, Bonn, Nice, Amsterdam, Hannover and Paris.

Warlikowski became known in the second half of the 1990s but the turning point was in 2001 when he directed Oczyszczeni (Cleansed) by Sarah Kane. The production was also one of the most important events in Polish theatre of that decade. It depicted the contemporary world as empty and devoid of God. It could be said that the testing and reconstruction of broken inter-human relations constituted the main axis of the play. The reconstruction being tragic and imperfect, the sexual union of the characters was something that took place through bloody experiments, with the final image of joined mutilated bodies.

African Tales According to Shakespeare, dir. Krzysztof Warlikowski

African Tales According to Shakespeare, dir. Krzysztof WarlikowskiWarlikowski avoids literalism and journalism – in his image of contemporary world and humankind he refers to the universalist way of thinking. What is important here is the experience of the director earned during work on classical and Shakespeare plays that he frequently drew on in the 1990s. Of his first experiences with theatre, the director has said:

In Krakow, I saw the productions of Konrad Swinarski, Jerzy Jarocki, Andrzej Wajda and Krystian Lupa. Abroad, in France, I did not happen upon any interesting theatre, and as a result I spent my evenings at the opera or ballet. What I saw there were hardly revolutionary productions, but they were undoubtedly beautiful and manifested a sense of style. I saw Baroque theatre productions at the Opéra Comique, operas at the Opéra-Garnier, and at the Odéon I saw the productions of Ingmar Bergman, Giorgio Strehler and other guest artists (...)

("Notatnik Teatralny" / "Theatre Notebook," 2003, no. 28-29)

Warlikowski also had an opportunity to meet Peter Brook, Ingmar Bergman and Giorgio Strehler personally by taking part in workshops they led. Brook ultimately asked the young director to work with him on an operatic production titled Impressions de Pelleas, based on Claude Debussy's Pelleas and Melisande (Buffes du Nord, Paris). Of his studies under Lupa, Warlikowski has said:

Everyone should meet someone like him as early as possible in their life. His mind has been shaped by a different set of readings and a different generational experience. We are linked, however, by the manner in which we seek to open up the theatre to many different issues.

("Notatnik Teatralny" / "Theatre Notebook," 2003, no. 28-29)

Some of Warlikowski’s most controversial and loud productions include his stage adaptations of Kotles and Sarah Kane, with the production of Cleansed a particular milestone in the director’s career. However, with time, a recurring and indispensable point of reference for his oeuvre is the Shakespearian body of plays. And Warlikowski explores these Renaissance pieces from his own contemporary perspective. Theatre critic Roman Pawłowski states:

(...) without restraint [Warlikowski] has introduced elements of contemporary reality onto the stage (...) However, the director's intrusions into the world of Renaissance comedy do not stop at dressing his heroes in jeans and sport coats. Warlikowski has performed fundamental reconstructions of the meanings of these plays, filtering them through contemporary thinking. His "Taming of the Shrew" became a story about breaking a woman's character and depriving her of her freedom. (...) He transformed "The Winter's Tale" from a fantastic fairy tale with dancing, pastoral scenes and singing into a bitter story about the decline and dismantling of a family.

("Notatnik Teatralny" / "Theatre Notebook," 2003, no. 28-29)

Warlikowski also stages operas.

Barbara Hannigan and Tom Randle in Berg's Lulu directed by Warlikowski at La Monnaie, photo: Bernd Uhlig / La Monnaie

Barbara Hannigan and Tom Randle in Berg's Lulu directed by Warlikowski at La Monnaie, photo: Bernd Uhlig / La Monnaie Opera is a prison - says the director. - The extent to which we can create an enclave of freedom within it is the most fundamental and most important problem. The director's task is thus to inject life into the structures imposed by the score and ossified conventions.

("Rzeczpospolita", 2004, no. 224)

Theatre can not show life directly. It is a metaphor. It does not have to name. It provokes, irritates and discusses the problem. It is not a theatre where one comes to have a nice time. The drama for our experts in Romanticism, Fredro or Gombrowicz. What meaning should it have? We have to wake up and start to touch the audience, like Swinarski did, let these people live the play like a Spielberg film. Make them remember it for days.

(Krzysztof Warlikowski, "Rzeczpospolita")

The Borderlands of Alternative Theatre

The alternative theatre, which played an important role in the 1970s and later, is less exposed today. The very name "alternative" is now revised and seems less relevant. The political situation which determined the position and constitution of the alternative movement has changed. The repertoire theatre has changed. The formal borders between the repertoire theatre and alternative movement are blurred, and thus it is perhaps more appropriate to talk about non-institutional theatre in economic and organizational terms, although not entirely so. Contrary to the American way, for exemple, in the contemporary democratic Poland, independent institutions also rely largely on state subsidies.

When trying to name and isolate what is commonly called alternative theatre, it is helpful to look at the continuing activity of several well-known groups (Teatr Ósmego Dnia and Akademia Ruchu). Less known or simply younger emerging groups, such as Porywacze Ciał, Biuro Podróży, Komuna Otwock, somehow also refer to this tradition.

A separate position in Polish theatrical life is held by Ośrodek Praktyk Teatralnych Gardzienice [Gardzienice Centre for Theatre Practices] under the management of Włodzimierz Staniewski. The group has been active since the mid-1970s and it has gained international fame and recognition. It very rarely prepares premieres. The last one was Electra, in 2004. The group’s performances are a way "back" or rather "toward the roots" of culture, from eastern European folk culture to medieval and ancient culture. The work of the group resembles archaeological activity: performances are preceded by thorough anthropological and ethnological research. The recent performances were an attempt to reconstruct ancient music and dance – two passions which give rise to Gardzienice productions. This archaeology, however, is transferred into a live, intensive theatre.

The position of the group is distinct also due to the number of theatrical teams which originate from it. The most important include: Studium Teatralne, Teatr Pieśń Kozła (Song of the Goat Theatre), Węgajty, and Chorea. And all of those troupes manifest a strong reference to the discoveries of Jerzy Grotowski. The founder and director of Studium Teatralne – Piotr Borowski, as well as that of Chorea – Tomasz Rodowicz – had collaborated with Jerzy Grotowski in the very beginnings of their artistic paths.