Polish Jazz is approaching its 100th anniversary. What makes the history of Polish Jazz so unique is its role in the quest for democracy and political freedom during the communist period and its being deeply rooted in Polish traditional culture. In the 20th century, jazz was in the avant-garde of democratic processes in Poland and was strongly linked with all genres of art that struggled for artistic independence. The difficult circumstances of the communist period and the need to redefine its position after the political transformation left no space for stagnation.

To start your adventure with Polish jazz, choose your profile:

I have a day off and I want to know it all

I am a jazz archaeologist; I want to look for the footprints of the first Polish jazzman

I love those who make use of music to rebel against evil powers

I have all the recent ECM releases on my shelf. Only spacious, open, lyrical jazz interests me

Is there a Polish incarnation of John Coltrane?

I love James Dean, but I’d also like to meet somebody who got over his turbulent youth years and successfully continued his artistic career

Hard bop is my religion, and Jazz Messengers are my prophets

I waste no time listening to those who never cooperated with Miles

Jazz is OK but I prefer the Sex Pistols. Is there anything in between?

The history of Polish Jazz is great, but how about the 21st century?

Before World War II

Immediately after World War I, the New American Music - jazz - began its European expansion, sweeping the continent from west to east, and from north to south. In 1923, the first Polish jazz band was founded; it was called The Karasiński & Kataszek Jazz - Tango Orchestra and became Warsaw's most popular dance orchestra, playing in popular nightclubs and revue theatres. In 1934-1935, they even toured Europe and the Middle East.

Other popular bands of that era include Lofka Ilgowski Orchestra heavily influenced by Benny Goodman's style, and The Petersburski & Gold Orchestra, with leaders Jerzy Petersburski (piano), and Arthur Gold (violin). During the rest of "the 1920's Jazz Decade", The Petersburski & Gold Orchestra established itself as the most popular dance orchestra in Warsaw, performing at its most fashionable restaurant "Adria".

All of them, besides regular concerts, often worked for the film industry, contributing to countless films produced in Poland during the 1920s and 1930s. Poland's first record label - Syrena Records (created in 1904) started documenting the first recordings of Polish jazz.

The boom of the professional jazz movement in Poland in the early 30s was due, most of all, to the fact that when, after 1933, fascists came to power in neighbouring Germany, many musicians of Jewish provenance left. They came to Poland. Consequently, the receptive and resource-hungry Polish Jazz society was strengthened by Ady Rosner's trumpet, Erwin Woheller's saxophone and Arkady Flato's swing band.

Trumpeter Ady Rosner soon became the best and the most popular Jazz musician in Poland. He formed a swing orchestra with Polish musicians, enchanting audiences and gaining wide recognition among critics. The orchestra's vocalist Ludwig Lampel was hailed by the critics as 'a sensational singer of European jazz'. Rosner's bands not only achieved national recognition but also an international reputation, touring extensively throughout Latvia, Denmark, Hungary, the Netherlands, and France, where he recorded three albums for the French division of Columbia Records. Later on, after escaping the Nazi / Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, Rosner emigrated to Russia where he went through series of unbelievable "alternative lives": from being the highest paid musician in all Russia to a gulag prisoner, to (after Stalin's death) the driving force in Soviet Jazz. Rosner left Russia in 1973 and died in Berlin, Germany in 1976. Ady Rosner's input to the beginnings of Polish (and Russian) jazz is unquestioned and unparalleled by any other musician of that time. Most of the bands of that era played many different styles of dance music, and so did Rosner, but what distinguished his band was his mastery and focus on swing. During his time in Poland, Ady Rosner gained the name of "the King of Jazz Virtuosos". One Polish critic wrote: 'Ady Rosner - Jazz sensation!', and in the British publication Melody Maker, the president of 'Sweet and Hot Club of Brussels', called him 'The Polish Armstrong!'.

Ady Rosner and his swing orchestra, photo: CC

Ady Rosner and his swing orchestra, photo: CC

After WWII: the Catacomb period

Consequently, like the rest of Eastern and Central Europe, Poland fell under the dominance of Stalinist Russia - and the Soviets certainly did not dig swing! Only certain musical forms were allowed to flourish, particularly those with folk rhythm, without syncopation. One tempo was prescribed for everybody and army marching bands rose in importance.

In Stalinist Poland, jazz music was banned along with modern art, decent toilet paper and the right to travel abroad. Ruled with the 'iron fist', the cultural policy of the government excluded all forms of modern art, demanding from the artists to follow the mantra of 'socialist realism'.

Thankfully not everybody dug Stalin and toed the party line. Young people in Poland with no taste for Russian recipes or Soviet music and political doctrines, but longing for freedom, rediscovered jazz. Banned and sometimes even persecuted, jazz went underground, or, as was said, into 'the catacombs'. Jazz could only be played at private homes and private parties. Since the late 1940s in Poland, jazz, although not officially existing, in fact, had embraced the spirit of independence, nonconformity and cosmopolitanism.

One band came to dominate the hidden landscape of the Polish jazz scene. The name of this group was Melomani (The Music Aficionados). The ensemble was established in 1947 from among the hippest cats of the day, including 'The Founding Fathers of Polish Jazz': Jerzy 'Duduś'" Matuszkiewicz (leader, saxophones, and clarinet), Andrzej Trzaskowski (piano), and Krzysztof Komeda (piano).

Many of them were students of the Łódź Film School, famous for establishing one of the leading European film movements and commonly referred to as the "Polish Film School". Musicians of Melomani hung out at the Łódź YMCA, one of the few existing oases for nonconformists and independent thinkers in the Poland of the late 1940s. Having been separated from the development of Western jazz and without any jazz recordings or publications, Melomani played the sort of music that they thought was jazz, such as Jelly Roll Morton and W.C. Handy. Critic Elliott Simon said it the best:

Melomani played a series of standards with enthusiasm exceeded only by their fans' obvious adoration...it is however, the historical circumstance - when jazz was a high energy outlet for the creativity of a culturally repressed society.

Melomani, photo. Witold Sobociński's archive

Melomani, photo. Witold Sobociński's archiveOf course, there was no jazz music on the Polish radio, no jazz records in the stores, no books and no sheet music for sale. However, there was the will, the enthusiasm and the Voice of America. Instead of listening to reports about the success of the Soviet Union at achieving heaven on earth, jazz fans and aspiring jazz musicians tuned their Soviet-made radios to DJ Willis Conover's programmes. For Polish jazz devotees of the late 40s and early 50s in Poland, Willis Conover was a musical messiah. Conover's programmes allowed access to the desired alternative: the right stuff and the real thing. His contribution to Polish jazz would never be forgotten.

The ‘thaw’ – 1950s and 1960s

Despite the political obstacles of the 1960s, cultural and intellectual life in Poland continued to thrive throughout this and the following decades. Not surprisingly, in the 1960s, Polish jazz became one of the most important elements of cultural revival. Growing from its infancy into maturity, it became more diverse, more sophisticated and more stylish. During the 1960s, Polish jazz evolved into three basic styles: Dixieland (traditional), straight-ahead (mainstream), and avant-garde (free).

The increased interest in jazz also blossomed into a growing acceptance of more demanding styles. It is difficult to clearly mark the distinction between mainstream and avant-garde jazz in the Polish jazz of the 1960s and 1970s; too many musicians walked the fine line between the two. Perhaps the best approach to analyse modern jazz in Poland is to focus on its leading figures.

Krzysztof Komeda

Krzysztof Komeda, photo: Marek Karewicz / from the Kordegarda Gallery

Krzysztof Komeda, photo: Marek Karewicz / from the Kordegarda GalleryThe most important artist of the 1960s and in the whole history of Polish jazz was Krzysztof Komeda (real name Krzysztof Trzciński). He was born on April 27, 1931, in Poznań and started playing piano at the age of seven, but the war ruined any chance of him becoming a concert pianist.

He studied medicine at Poznań and chose to be a laryngologist. He picked his childhood alias "Komeda" for his artistic alter-ego - in 1950s Poland it was not possible for a reputable M.D. to play "the decadent music of the West" - jazz. He was one of the founders of legendary band Melomani; his professional jazz pianist career started at the 1st Sopot Jazz Festival in 1956 with Janusz Grzewiński's Dixieland band and his own Sextet. He continued his jazz career in Poland and Scandinavia for the next 12 years with his own bands (Combo, Trio, Quartet, Quintet, Sextet), which dominated the modern Polish jazz scene.

Komeda's role in Polish jazz cannot be explained in just a few sentences. Words like: genius, composer, visionary, collaborator and leader cannot fully describe him. How could this talented but not by any means virtuoso pianist with a medical degree make such a great impact on Polish jazz? How could all of the musicians who played with him emphasise what an overwhelming impact his music and his personality made on them? Komeda's long time collaborator Tomasz Stańko commented:

Komeda was a very quiet man. At rehearsals he told us nothing, nothing. He would give us a score and we would play and the silence was very strong and intense. He wouldn't say if we were right or wrong in our approach. He'd just smile. He was such a strong force, the music was so original and he always gave me plenty of space for self-expression and interpretation... He showed me how simplicity is vital, how to play the essential. He showed different approaches, using different harmonies, asymmetry, many details. I was very lucky that I started out with him...

His unique sound has to a lesser extent to do with conventional jazz-style timing, but rather with Slavic lyricism, 19th-century Polish romantic music tradition, and a variable treatment of time during the course of his compositions. He is widely credited as being one of the founding fathers of the uniquely European style of jazz composition.

During his life, Komeda released only one album, Astigmatic (Polskie Nagrania – Muza Recording Label), which the Penguin Guide to Jazz called "Simply - Essential!". A new release with more influence on Polish jazz has yet to be recorded. Another field where Komeda excelled and achieved world class status was his work for motion pictures; he wrote music for over 40 films, including such Polish cinematic classics as Andrzej Wajda's Innocent Sorcerers. He also collaborated with other Polish directors: Jerzy Passendorfer, Jerzy Skolimowski, Janusz Morgenstern, Jerzy Hoffman, Leonard Buczkowski, Janusz Nasfeter, and renowned Danish film director Henning Carlsen. Especially important was his very fruitful collaboration with director Roman Polański that included the soundtracks to Two Men and a Wardrobe, Cul-de-Sac, Knife in the Water, Fearless Vampire Killers and Rosemary's Baby.

Krzysztof Komeda, photo: Marek Karewicz / archive of the Kordegarda Gallery

Krzysztof Komeda, photo: Marek Karewicz / archive of the Kordegarda GalleryIn December 1968 in Los Angeles, when working on Rosemary's Baby, Komeda had a mysterious accident which led to his death due to brain damage. Decades have passed after Komeda's tragically early death at the age of 38, but despite the passing of time, his music is still alive, inspiring new artists and conquering new hordes of listeners. Countless Polish jazz musicians have been exploring the legacy of Komeda and his songbook, with Tomasz Stańko and Leszek Możdżer being the most famous torchbearers.

Tomasz Stańko

Tomasz Stańko, photo: Marek Dusza

Tomasz Stańko, photo: Marek DuszaIn 1962, 20-year-old trumpet player Tomasz Stańko and pianist Adam Makowicz created the Jazz Darings, later described by jazz critic J. E. Berndt as the 'first European free jazz combo'. Stańko was a graduate of the Kraków Academy of Music, when, in 1963, he received an invitation from Krzysztof Komeda to join his band. Their collaboration lasted until Komeda's tragic death. Komeda's music had a significant impact on the young Stańko, who admitted:

The lyricism, the feeling of playing only what's essential, the approach to structure, to asymmetry, many harmonic details. I was so lucky that I started out with him.

In 1968, Zbigniew Seifert joined the newly formed Stańko Quintet, soon switched from alto sax to electric violin, and the next chapter of European jazz history began. Beside Stańko and Seifert, the line-up of the quintet included Janusz Muniak on the saxophone and flute, Jan Gonciarczyk / Bronisław Suchanek on the bass and Janusz Stefański on the drums. The quintet made three records: Music for K (1970), Jazz Message from Poland (1972) and Purple Sun (1973) but the albums could not compare to the magic of the quintet's life performances. Stańko Quintet disbanded in 1973, at the peak of its creative potential and after achieving a cult-like following in Europe. Always interested in musical progression, Stańko went through a period of fascinating collaborations with artists including Alex Schlippenbach Globe Unity Orchestra, Krzysztof Penderecki, Don Cherry, Stu Martin, Dave Holland, Garry Peacock, and Jan Garbarek. He also experimented with electronics and electro-acoustic sounds, as well with the concept of concerts of solo trumpet at places as unusual as the Taj Mahal in India. His most important work of the 1970s may have been with Finnish drummer Edward Vesala. Their series of albums, which included Balladyna and TWET, defined new directions for improvised music in the next decades.

In the beginning of the 1980s, Stanko entered a short-lived partnership with inFormation, a trio lead by McCoy Tyner, which proved very important for Stańko's career. The trio influenced pianist Sławomir Kulpowicz, one of the most innovative bass players in Europe - Vitold Rek, and the legendary drummer Czesław "Mały" Bartkowski. As a quartet, they recorded two albums in Poland in early 1980s: A i J and Music 81, capturing the period of political turmoil and social oppression - martial law. Stańko's cooperation with inFormation is a fascinating document of artistic freedom, independence and creativity; musically leaping forward to another of Stańko's quartets from the beginning of the 21st Century (Marcin Wasilewski, Michał Miśkiewicz, Sławomir Kurkiewicz). Stańko was also briefly part of Cecil Taylor's big band in 1984. Shortly afterwards, he formed another ensemble, Freelectronic, and experimented with post-Miles musical concepts on albums Lady Gone, Chameleon and C.O.C.X. Always inspired by writers like William Faulkner, William S. Burroughs, and James Joyce who were famous for their "improvised narration"; Stańko spent part of the 80s exploring the legacy of Polish writer Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy), with whom he shared an interest in the influence of narcotics in the process of artistic creation. His 'Witkacy period' awarded his fans with album Peyotl - Witkacy. Commenting later on his use of drugs, Stańko concluded:

As Jimi Hendrix once said: 'Drugs are for adolescents'. Perhaps it took me a while, but I am not a kid any more.

The beginning of the 1990s brought a final articulation of the mature Stańko's style. His first album of the new decade was Bluish, released by Krzysztof Popek's label Power Bros. Following this breakthrough album, Stańko re-established an alliance with ECM Records, which had issued some of Stańko's most acclaimed works, including Matka Joanna; Leosia, which featured pianist Bobo Stenson; Litania - a tribute to Komeda; a cross-continental ensemble featured on From the Green Hill, and series of albums with Marcin Wasilewski (piano), Sławomir Kurkiewicz (bass), and Michał Miśkiewicz (drums) that received uniform acclaim among critics and Jazz fans worldwide. In 2002, after votes from 21 distinguished European jazz critics, he received the very first European Jazz Award, which is intended to honour the most outstanding European jazz musicians. To date, Stańko is collaborating closely with ECM records and releases high-quality albums with various bands composed of the most talented young musicians from Scandinavia and the USA.

Zbigniew Seifert

Zbigniew Seifert, Warsaw, 1970s, photo: Marek A. Karewicz / FORUM

Zbigniew Seifert, Warsaw, 1970s, photo: Marek A. Karewicz / FORUM Starting his brilliant career in the late 1960s, Stańko Quartet alumni Zbigniew Seifert quickly became a leading European jazz voice and the first violist capable of "transcending" the spirit of Coltrane's music. Born on June 6th, 1946, he began studying violin at the age of six and ten years later also took up the saxophone. He studied violin at the University of Kraków, while also playing alto in his Jazz group. The music of John Coltrane proved to be a strong influence throughout Seifert's career. As Scott Yanow observed:

Zbigniew Seifert was to the violin what John Coltrane was to the saxophone.

From an early age, and later on as a member of Stańko's Quintet, (1969-1973), he made a name for himself in Europe. As a leader, Seifert (who was affectionately known as Zbiggy) performed music that ranged from free Jazz to fusion. During his short life, he was thankfully able to collaborate with some of the brightest stars of both American and European Jazz, including Hans Koller, Joachim Kuhn, Billy Hart, Michael Brecker, John Scofield, Eddie Gomez, Charlie Mariano, Jack DeJohnette, and the band Oregon, with whom he recorded the masterpiece album Violin. In the mid-to-late-seventies, Seifert recorded a series of albums as a leader that established him as one of the most unique voices in jazz and one of the most sophisticated improvisers on the violin. Tragically, his promising American and world career abruptly ended with his death to leukaemia in 1979.

Zbigniew Namysłowski

Zbigniew Namysłowski at the Jazz Jamboree in 1966, photo: Tadeusz Wackier / FORUM

Zbigniew Namysłowski at the Jazz Jamboree in 1966, photo: Tadeusz Wackier / FORUMWillis Conover said this about Zbigniew Namysłowski:

When I first visited Poland, I was quite unprepared to hear Polish musicians at so high a level. Namysłowski was clearly the best. International voting has proved that audiences in Europe recognize the best Polish musician as among the best anywhere in the world. He honours 3 traditions, of Jazz, of Polish, of himself. Anyone who misses Namysłowski is missing a unique source of creativity in 20th century. Namysłowski is a giant!

Namysłowski is a master of many instruments. From the age of four he played piano, he mastered cello at twelve, then studied music theory in Warsaw. He initially (the 1950s) played trombone in Polish Dixieland, and in the 1960s, he took up the alto saxophone and ventured into modern jazz, joining Andrzej Trzaskowski's hard bop group the Jazz Wreckers. In 1963 he formed his first quartet, with whom he recorded ground-breaking album Lola for England's Decca label. Namysłowski cites John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Wayne Shorter, and Joe Henderson as his favourite musicians but also draws inspiration from other sources, including blues, rock, and traditional Polish, Balkan, and Indian music. Namysłowski is also a very successful composer, including genres outside of jazz and encompassing anything from the Polish version of funk to sophisticated pop music. In the field of composition, Namysłowski has created his own unique and easily recognizable language: the harmonic language, the swing that goes beyond the scale of musical transcription, the jazz tradition, and his always present appreciation of Polish musical folklore. Besides being a ground-breaking visionary of Polish jazz, his role in Polish jazz could be compared to the impact of Art Blakely's Jazz Messengers on jazz history - he become a distinguished mentor of young musicians. Even today, Namysłowski remains himself and is always refining his own musical language. To quote Maestro Namysłowski himself:

To be successful, it is no longer enough to play Horace Silver themes. One shouldn't play material borrowed from records (...) I founded my own quartet and created my music to play what I want to and how I want to.

Adam Makowicz

Adam Makowicz, photo: Jan Bebel / FORUM

Adam Makowicz, photo: Jan Bebel / FORUMAdam Makowicz is another of the real geniuses of Polish jazz. His brilliant carrier spans decades and until today, he always amazes jazz fans with his virtuosity and swing. An alumnus of a variety of styles, including both electric and acoustic configurations; since 1974 Makowicz has been performing mainly as a soloist. He is a virtuoso pianist, with his own personal style, both in his own compositions and in piano interpretations of works of other composers. His style is a combination of the American tradition originated by Tatum and George Gershwin, with elements of European music referring to the romantic tradition. Today, Makowicz is devoting more and more time to his own interpretations of classical standards written by composers such as Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and George Gershwin. His recitals are addressed to a large extent to audiences of philharmonics. The musician himself currently describes his music as 'closer to classical music than to jazz'. This trend incorporates his compositions written for piano and for small bands. As Jim Fuselli once wrote about Makowicz in The Wall Street Journal:

Adam Makowicz has been praised by Benny Goodman, compared with Art Tatum, Erroll Garner and Teddy Wilson, honored by jazz publications and toasted all over Europe as a genius. Mr. Makowicz's fiery style, firm chording, and rapid, Tatumesque right hand phrasing make him more than deserving of the accolades he has received.

Michał Urbaniak

Michał Urbaniak, photo: Eugeniusz Helbert / FORUM

Michał Urbaniak, photo: Eugeniusz Helbert / FORUMIn the 1970s and 1980s, Michał Urbaniak was probably the best internationally known Polish jazz musician. A prodigy of various Komeda's bands and leader on his own from the late 1960s, his worldwide career began in 1973, when Columbia published his ground-breaking album. Since then, his passion has been continuing with varying fortune. But throughout the years of his artistic calling, all the elements of his ingenious personality were always there: straight-ahead expression, paired with Slavic ingenuousness, musical eclecticism, contemporary articulation and the influence of Polish folk music - all flawlessly incorporated into the vocabulary of American jazz. From 1975 to 1989, Urbaniak was the leader of Michal Urbaniak Fusion, a renowned band which played at the best concert halls and clubs all over the US (Village Vanguard, Village Gate, Carnegie Hall, New York Jazz Festival, Newport, Washington). At that time, he had a chance to play with the biggest jazz legends of all-time, such as George Benson, Lenny White, Wayne Shorter, Marcus Miller, Billy Cobham, Joe Zawinul, Ron Carter, Stéphane Grappelli and Miles Davis. Playing with Miles at that time meant more than winning any prestigious award. Davis is reported to have said on this occasion:

Get me this f***ing Polish fiddler, he's got the sound!

The beginning of the 1990s was the culminating point of his career: his name was mentioned numerous times in various categories of important jazz surveys, including of the prestigious "Down Beat". In his compositions, Urbaniak has always attempted to integrate the latest trends of world jazz with elements of his own personal style. He brings together the original, easily recognisable sound of his instrument with current musical conventions. In his continued pursuit for new inspirations and new sounds, Michał Urbaniak is probably as close to Miles Davis' spirit as any Polish Jazz artist could be.

Yass: the jazz, the filth and the fury

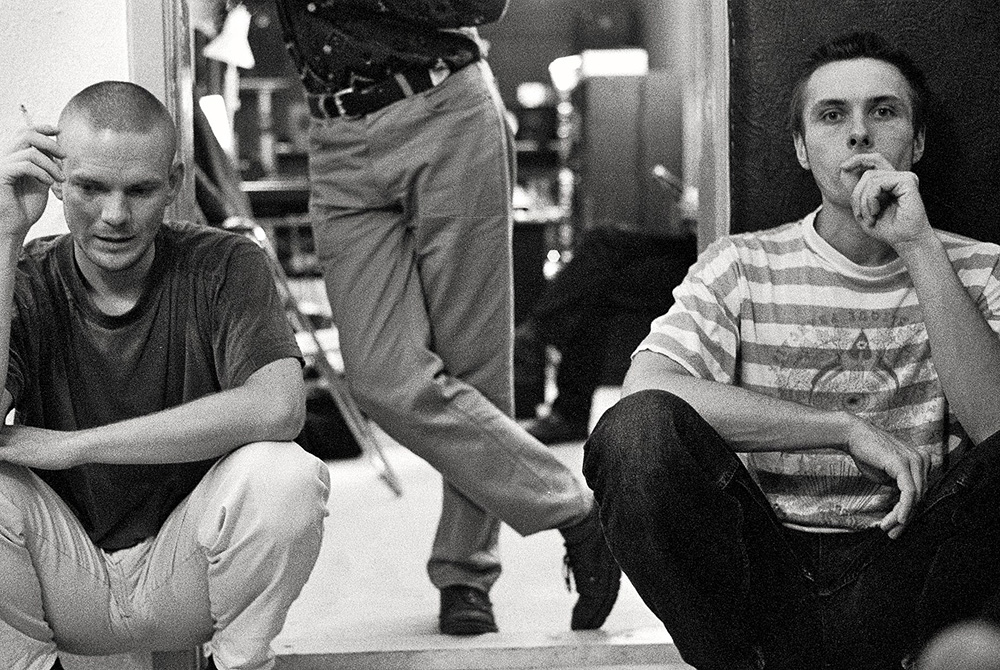

Yass movement protagonists, photo: Krzysztof Szymanowski, courtesy of the author

Yass movement protagonists, photo: Krzysztof Szymanowski, courtesy of the authorThe 1990s saw the birth of a musical trend that wanted nothing less than to turn the established order of things to ash by the most drastic of means. This new trend was called yass. The recipe for artistic revolutions is built upon the critique of ancien régimes and the tossing of old masters off their pedestals. Yet, Yass took up this battle on an entirely different scale, rebelling against everything: the authorities, a slovenly society, the media, the consumerism of the early capitalist period, the canon, the lack of colour, language and even the weather.

10 names to know in contemporary Polish jazz

The Polish jazz of A.D. 2014 offers two generation of outstanding musicians. On one side, there are venerable masters, already acclaimed and widely known and recognised. On the other side, there is a huge group of creative youngsters, often graduates of the best jazz departments in the world. This abundance of talent would require a separate article to be written about. What might, however, give you waypoints for a further journey is this list of 10 outstanding Polish jazz masters:

(in alphabetical order)

- Lado ABC - Warsaw-based music label founded in 2004 by a community of musicians. The most creative conglomerate of personalities in improvised music nowadays.

- Marcin Masecki - pianist, composer and producer whose style oscillates between jazz, classical and experimental music. Once you see him, you'll never confuse him with anybody else.

- Mikrokolektyw - a duet that continues to explore the boundaries of jazz, post-jazz and free improvisation and records for ultimately celebrated Delmark Records.

- Leszek Możdżer - pianist, composer and arranger, considered the greatest revelation of the Polish jazz of the last decade.

- Maciej Obara - young prophet of the jazz saxophone. A true virtuoso with heart and soul!

- Włodzimierz Pawlik - most recent Polish Grammy Music Award winner. A recognised pianist, composer, arranger and educator.

- Pink Freud - jazz/punk/avant-garde band that will make you dance and shout even if you are a calm person.

- Tomasz Stańko - jazz trumpeter and composer, one of Europe's most original jazz musicians and most recognisable Polish jazz musician.

- Dominik Wania - a tranding pianist, student of Danilo Perez, extremely creative and skilled. Member of all-star Noise Trio.

- Marcin Wasilewski Trio - a trio recognised for their unique talent in blending tradition with conte a porary sound. Ex-bandmates of Tomasz Stańko.

Source: Most parts are taken from Cezary Lerski's article 'Polish Jazz - Freedom at last'; editing, comments, foreword, listener's profile and last two paragraphs written by Wojciech Oleksiak on 30 Jun 2014.