Here are a few indicators to help orient yourselves across more than a millennium of Polish architecture.

1. Egyptians have pyramids, Romans have the Colosseum, and the British have Stonehenge. So, what are the oldest monuments in Poland?

2. Santi Gucci, Tylman van Gameren, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Rainer Mahlamäki – were Polish buildings ever built by Poles?

3. Buildings and politics – Polish architecture of the 20th century gains independence twice

4. The Mazovian hexahedron, the gentry manor and a modernist cube – the homes of Poles

5. Warsaw is the administrative capital of Poland, Kraków is its tourist capital, but there is also a city which is the capital of Polish architecture.

6. Almost any architect can design a building, but the real skill lies in urban planning

7. Rationalism is boring! We want something wild!

8. Poland in the European Union is like one big construction site

Egyptians have pyramids, Romans have the Colosseum, and the British have Stonehenge. So, what are the oldest monuments in Poland?

According to historians, the beginnings of the Polish state date back to the 10th century AD. The state began forming after the union of two neighbouring tribes – the Wiślanie (Vistulans), who dwelled in the area of modern-day Kraków, and the Polanie, who lived to their north-west, around present-day Poznań. These are the regions which have preserved remains of the oldest Polish buildings. They are mainly shrines. This is due to the fact that homes were made of wood and clay, which did not survive the test of time, while churches were raised in stone.

Wawel Royal Castle (right) and the Cathedral (left) in Kraków, photo: CC

Wawel Royal Castle (right) and the Cathedral (left) in Kraków, photo: CC The Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków preserves fragments of a church from the second half of the 10th century. Relics of religious constructions can also be found in Poznań and Gniezno. The oldest buildings that have been preserved in their entirety were raised in the 12th century. The Church of St. Prokop, a stone rotunda construction built in the Roman style was raised in around 1160 in Strzelno. It is composed of a tower shaped like a horseshoe, and is also the only Roman shrine in the world with a rectangular presbytery.

The three-nave collegiate church in Tum, photo: Mrksmlk, CC

The three-nave collegiate church in Tum, photo: Mrksmlk, CCAn exquisite treasure of the Polish Middle Ages was raised in the same epoch, in the Mazovian town of Tuma near Łęczyca. A stone three-nave collegiate with two towers, decorated with sculptures (including a 12th century portico, still preserved today), with a simple, even raw, character. Built with basic geometric forms, it resembles a fortress. All of this is due to the fact that when large-scale buildings were raised in Poland at the time, German masons were employed. This resulted in an import of the style that was popular among Poland's western neighbours.

Many of the architectural monuments from the Roman and Gothic periods preserved to this day were once part of monasteries. The first orders to settle in Poland in the 10th century were the Benedictine and the Cistercian monks. Benedictine abbeys in Tyniec, Mogilno, and Łysa Góra, and Cistercian abbeys in Jędrzejów, Koprzywnica, Wąchock, and Sulejów underwent subsequent architectural modifications and expansions. However, hints of the ancient, medieval walls can still be observed in them.

Santi Gucci, Tylman van Gameren, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Rainer Mahlamäki – were Polish buildings ever built by Poles?

In the 21st century, it comes as no wonder that significant buildings for public use are designed after an international competition selects a winning project from the many proposals submitted by architects from across the entire globe. Thus, Dutch architects build in the Middle East, the English – in China, and Americans in Spain. Thanks to these processes and the competition procedure, Poland also boasts an array of excellent buildings designed by non-Polish architects.

One of the most interesting recent architectural works in Warsaw, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, was designed by the studio of Finnish architect Rainer Mahlamäki. The light glass chest of its exterior form, which perfectly fits the modernist surroundings, embraces a wavy, expressive interior.

Museum of the History of Polish Jews, main entrance, photo: Wojciech Krynsk

Museum of the History of Polish Jews, main entrance, photo: Wojciech KrynskThe Austrian Riegler Riewe Architekten team proposed hiding the Silesian Museum underground, allowing for a good exposition of the historic structures of the Katowice coal mine.

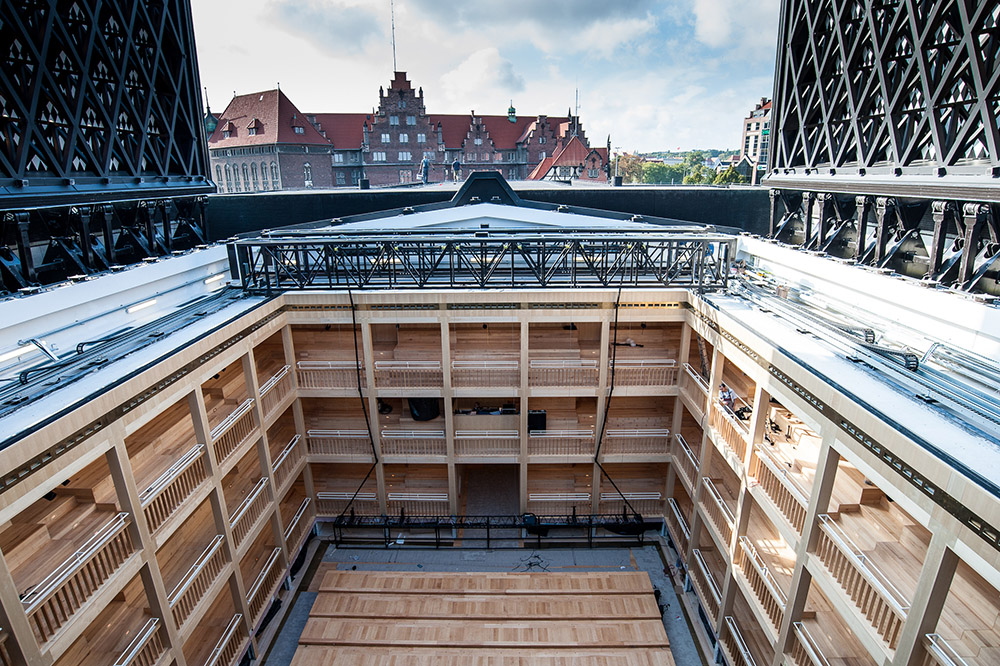

In 2007, the Italian duo Claudio Nardi and Leonard Maria Proli won the contest for a design which placed the Kraków Museum of Contemporary Art within the former Schindler Factory. The Italian-Spanish Estudio Barozzi Veiga studio created a visionary "iceberg" – the shooting white form of the the new Szczecin Philharmonic's headquarters. Another Italian, Renato Rizzi also recently designed the Shakespearian Theatre in Gdańsk, enclosed within a black brick windowless "box", and equipped with an retractable roof. The theatre was officially opened in 2014.

A view onto the scene of the Shakespearian Theatre in Gdańsk through the building's open roof, photo: Dawid Linkowski

A view onto the scene of the Shakespearian Theatre in Gdańsk through the building's open roof, photo: Dawid LinkowskiBut foreign architects began working on Polish territory many centuries ago. In the Middle Ages, they travelled to Poland as they were employed in constructing important monuments for which Poles lacked expertise. Later on, kings and princes brought over architects from countries considered as the most culturally developed. This is how the Florentine Santi Gucci made it to the Royal Castle of Wawel in the mid-16th century. He authored a couple of mannerist masterpieces. Using light and easily-formed limestone, the Italian sculpted decorative and expressive tombstones, filled with extravagant detail. In 1574-5, he carved the Wawel graves of King Zygmunt August and Queen Anna Jagiellonka. In 1595, he made the tombstone for Stefan Batory, and in 1586 – the memorials for Barbara and Andrzej Firlej in the church in Janowiec. At the same time, Santi Gucci also designed many buildings. The castles in Książ Wielki and Baranów Sandomierski in the south-west of Poland are true gems of the mannerist style. They playfully trick the perception, filled with architectural surprises, and yet they are elegant and full of style.

In the second half of the 17th century, the Dutchman Tylman van Gameren often worked for Polish aristocrats. Although he was a representative of the baroque, his works are temperate and elegant. Toned-down forms typical of van Gameren were given to palaces in Warsaw – the Krasiński family Palace and the Gniński-Ostrogski Palace – residences in Nieborów and Białystok, as well as St. Anna’s Church in Kraków and the convents Church of St. Bernardine and Church of the Holy Sacrament in Warsaw.

Krasiński Palace in Warsaw, view from the gardens, photo: CC

Krasiński Palace in Warsaw, view from the gardens, photo: CCBecause of its tumultuous history and the geographical location between two empires, the borders of Poland were moved numerous times. Thus, present day Polish cities have many works by Dutch and German architects. A souvenir of the past political and economic significance of Gdańsk are the works of Willen van den Blocke, and his son, Abraham van den Blocke. 17th-century Dutch architects and sculptors also worked in Gdańsk during the construction of the Wyżynna (Highland) and Złota (Golden) Gates, the Manor of Artus, the Fountain of Neptune, the Wielka Zbrojownia (Great Armory), as well as numerous tombstones and epitaphs.

Great Armory building in Gdańsk, a view from the Mariacka Towerk, photo: CC

Great Armory building in Gdańsk, a view from the Mariacka Towerk, photo: CCKamieniec Ząbkowicki in Lower Silesia, Kórnik, Antonin, and Buk – all of these are sites which have preserved the works of an important 19th-century classicist, Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Another Silesian city, Wrocław, is home to the Centennial Hall recently made a UNESCO World Heritage site, and designed by Max Berg in the early 20th century. Wrocław is also home to WUWA, an experimental modernist housing area, the work of German modernists, whose research would influence European house-building of the subsequent decades.

Centennial Hall (Hala Stulecia) in Wrocław, photo: Marek Skorupski / Forum

Centennial Hall (Hala Stulecia) in Wrocław, photo: Marek Skorupski / ForumBuildings and politics – 20th-century Polish architecture wins independence twice

In the 20th century, Poland regained its independence twice. The first time was in 1918, following 124 years of existence under the partitions. The second came in 1989, when the communist regime was successfully overthrown without any bloodshed. Both of these events were extraordinarily important and also impacted the development of architecture.

The two decades of the interwar period 1918-1939 proved to be an unprecedented time of blossoming artistic life. The regained independence influenced architects, some of whom began to design elegant and stylish venues for public use, which were to also become symbols of power for the reborn state (some of these architects include Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, Marian Lalewicz and Bohdan Pniewski).