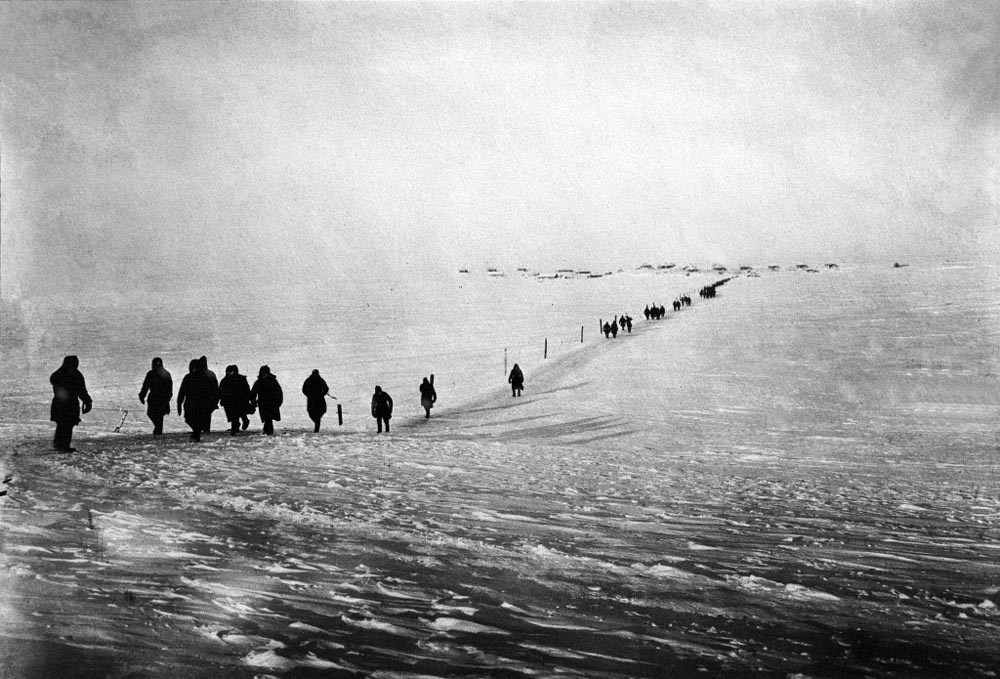

1. Poles deported to Siberia

Poles mass deportations to USSR. Photo: IPN

Poles mass deportations to USSR. Photo: IPN The travel took over two weeks (…). We stopped twice and they asked us to take snow and melt it and drink it.

Julian Mamos’ memory is of the mass deportation of Polish citizens to the Soviet Union that mainly took place between 1940 and 1941, after the Soviet Union seized half of Poland's territory in September 1939, in cahoots with the German Nazi invasion of Poland. The action was precisely prepared and performed by the infamous NKWD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs) and eventually resulted in the deportation of around 330-400 thousand of Poles.

People were given 15 minutes to pack their belongings, before they were loaded into train carriages (normally used to transport cattle or goods, not people). After a journey lasting over two weeks, they were ordered to disembark in the middle of Siberia and forced to work in the Soviet work camps. A considerable percentage of deported people died from hunger, exhaustion, frost and various diseases.

2. Unexpected freedom

Photograph from the album Gulag by Tomasz Kizny, photo: courtesy of IPN

Photograph from the album Gulag by Tomasz Kizny, photo: courtesy of IPN Two years in Siberia… yes. Later we got this act that we can go wherever we want.

When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, Stalin was forced to seek allies on the other side of the conflict. As a part of his dealings with the Allied Forces, he signed the Sikorski-Majski Agreement. According to its provisions, exiled Polish soldiers were released from their Soviet prison camps and allowed to reunite under General Władysław Anders who was forming the Polish II Corps. The army was created on the territory of the Soviet Union but due to endless sabotages from the Soviet administration, it quickly evacuated through Iran, Iraq and Syria to Palestine where it went under British command.

Some civilian ‘prisoners’ were lucky enough to join the army caravan, while others just like Justyna Szromek and her family were forced to try to go back to Poland on their own. They were given freedom but no means or help in returning home.

3. Nowhere to go at the end of the war

Anders' Army, AKA the Polish II Corps in Italy, February 1945. Photo: Reprodukcja FoKa/Forum

Anders' Army, AKA the Polish II Corps in Italy, February 1945. Photo: Reprodukcja FoKa/Forum When the war was over and there was a parade in London, there were no Poles…

The Polish II Corps finally made it to Europe and fought during the Italian campaign, contributing decisively to a crucial win in the battle of Monte Casino. Even though the war was soon over, Polish soldiers couldn’t return home. According to the Yalta, Potsdam and Tehran peace conferences, Poland fell on the communist side of the Iron Curtain. In Soviet-dominated Poland, the status of all the approximately 300,000 Poles who had been exiled during the war and sent to Siberia was uncertain since they were officially former Soviet ‘prisoners’. This applied especially to those who served in the Polish II Corps.

This is why, as Szczepan Wojtak recalls, Poles were not invited to the victory parade and instead of coming back home, a vast part of them went to England or dispersed all over Western Europe. The disappointment and resentment of Mr. Wojtak can be easily explained. Poles fought ferociously alongside the Allied Forces and were given almost nothing in reward. No free country, no chances of returning home, not even any splendour of victory.

4. Society’s aversion to newcomers

(My mother) loved my father and then… by certain people from her family she was rejected, believe it or not, because he was Polish.

Those who went to England faced a very difficult situation. First, they were located at the Winfield refugee camp but soon the British Army decided to disband any Polish troops and their wages were stopped. They had to start establishing a new life in Great Britain with little hopes of returning home one day.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom was very much shaken by the war at that time and was painstakingly trying to rebuild its economy and social order. Poles, who were war heroes as much as their British friends with whom they had fought arm-in-arm, suddenly became second-class inhabitants of the British Isles, accused of stealing jobs and social benefits. They became unwanted refugees.

5. Difficulty settling down

Here was a Polish lady making an English dish for the English friends of her daughter.

Poles’ blending into British post-war society was difficult for many reasons. Most of them didn’t speak English or only a little. Most thought they wouldn’t stay for good, and only until they were able to go back to Poland. Soon, the Cold War broke out and any thoughts of returning home were lost. In Poland, which was now under a communist regime, they were treated as foreign spies and enemy collaborators.

Forced to stay in the UK, they gradually started settling down and joining this new society – making friends, finding jobs, getting married to British wives and husbands, and starting to live a British life.

6. Dreams of a free homeland

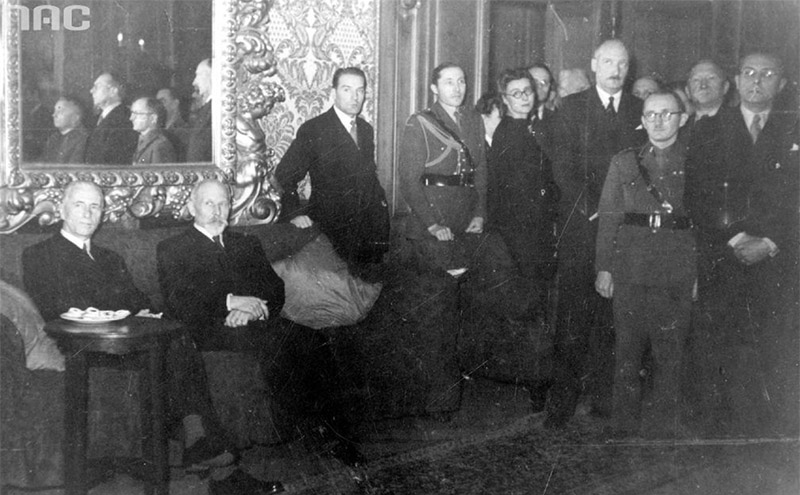

Meeting of high officials from the Polish government in-exile,

Meeting of high officials from the Polish government in-exile,

photo: www.audiovis.nac.gov.pl / (NAC) Polish tradition of enjoying yourself is one that I would heartily recommend!

Only a tiny percentage of Poles who settled in Great Britain ever returned to Poland. The communist era ended no sooner than 1989 so it came only in their very late years. As a substitute for their lost homeland, they organised Polish communities and clubs, expressed their attachment to the Polish government in-exile who resided in London until 1990, and they always celebrated Polish holidays and traditions.