Jan Dziaczkowski

Jan Dziaczkowski in his studio, photo: Marek Dusza

Jan Dziaczkowski in his studio, photo: Marek DuszaBetween 2002-2007, Jan Dziaczkowski studied painting at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts and during this time, he also co-founded an informal group called Nuku Workshop. After graduating, he released his debut album Collages which included his works Greetings From Holiday, Polish Art and Sleeping. In his series Keine Grenze, Dziaczkowski combined postcards from different European countries to create an alternative history of Europe after World War II where the Iron Curtain extended to Spain and Portugal, with the Roman Di Trevi fountain against the wall of the post-communist skyscrapers and more. He continued to create and innovate the medium until his untimely death in 2011 in the Tatra mountains.

Dziaczkowski’s collage style relied heavily on his technical expertise and his dedication to the medium’s small-scale capabilities. He was always collecting clippings from magazines and photos to create a massive pictorial repository. Some of his works would incorporate elements that would be 50 years apart, but would somehow create a physical harmony when placed side-by-side. His interest in Surrealists' games of cadavre exquis (French: exquisite corpse) and free association contributed to his perfect style of postcard-size collages and their inherent juxtaposition in the pieces.

Jan Dziaczkowski, 'Bauhaus, Dessau', from the series 'Keine Grenze', 2008, collage

Jan Dziaczkowski, 'Bauhaus, Dessau', from the series 'Keine Grenze', 2008, collageRoman Cieślewicz

Photo: Wojciech Łaski / East News

Photo: Wojciech Łaski / East NewsOne of the finest printmakers and poster artists of the second half of the 20th century, Roman Cieślewicz used multiple art mediums during his lifetime, including the collage. Cieślewicz was one of the founders of the Polish poster school which promoted an aesthetic striving for simplicity and clarity. After graduating from the Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, he moved to Warsaw to design posters for the Film Distribution Office (CWF), for the WAG state graphic agency and for the Polish Chamber of Foreign Trade. These jobs led to the development of his poster style, the Poster School and the founding of many visual art magazines. Although he died in Paris in 1996, his legacy in Polish visual culture lives on.

By bringing in the art of collage and photomontage into his poster making, Cieślewicz worked collages into a more mainstream visual culture. He understood the innovative and fascinating potential of collages and used the medium to convey larger themes and poetic metaphor in his posters. Inspired by the Russian constructivist avant-garde of the 1920s and by the Polish group Blok, Cieślewicz tapped into collages to make his bold and eye-popping posters that made him (and Poland) famous for their graphic design.

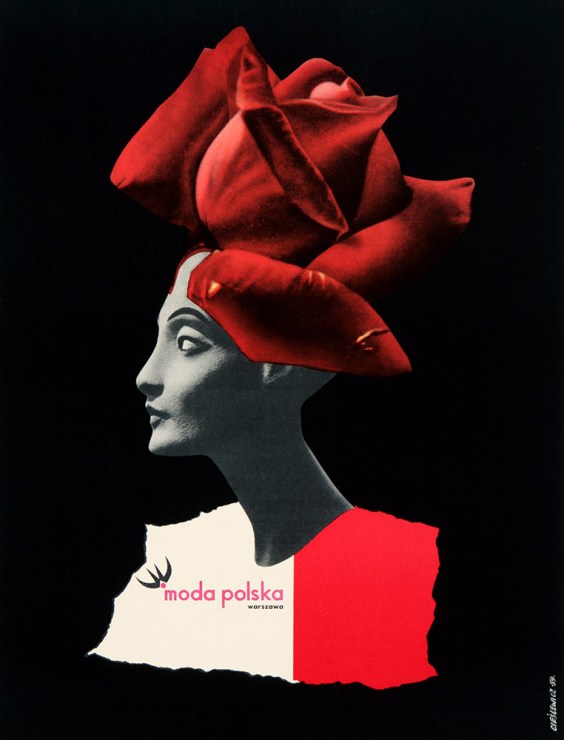

'Moda Polska (Polish Fasion House)' by Roman Cieślewicz, poster, 1959, photo: press materials

'Moda Polska (Polish Fasion House)' by Roman Cieślewicz, poster, 1959, photo: press materialsKarol Beyer

Karol Beyer, photo: National Digital Library Polona

Karol Beyer, photo: National Digital Library PolonaBorn in 1818, Karol Beyer was a photographer and the founder of the first photographic parlour in Warsaw. After attending and subsequently leaving school to go work for his uncle’s foundry, Beyer left for Paris, where he learned one of the first photographic techniques – daguerreotyping. He then returned to Warsaw to open the first photographic parlour in the city. Most of his work was in portrait photography, photographing the most prominent members of the political, cultural and artistic circles of Warsaw. He was always experimenting with different photographic technologies and ways to stretch the medium until he passed away in 1877 in Warsaw.

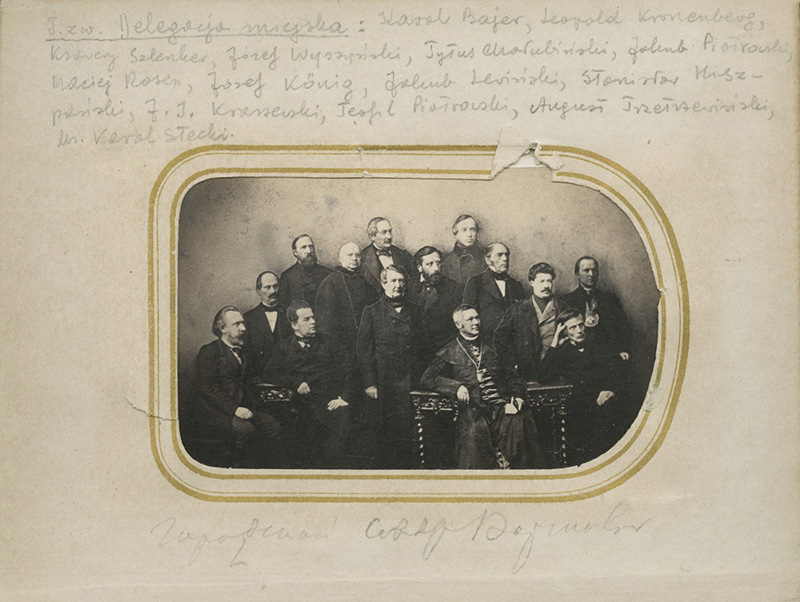

Although he was mainly a photographer, Beyer’s Members of the Civic Delegacy from 1861 was possibly the first Polish photomontage ever. In order to avoid the hassle of trying to get all 14 members of the Civic Delegacy together for a portrait, Beyer instead seemingly created a collage: he took photos of groups of members, cut them out and reassembled them into one coherent picture featuring all of the members. Little did he know, his little shortcut would spawn a generation of Polish collage artists in the years to come.

Karol Beyer, 'Członkowie Delegacji Miejskiej z 1861 roku' (Members of the Civic Delegacy), 1861, photo: property of Polish Academy of Learning, Special Collections, Scientific Library PAU and PAN, Kraków

Karol Beyer, 'Członkowie Delegacji Miejskiej z 1861 roku' (Members of the Civic Delegacy), 1861, photo: property of Polish Academy of Learning, Special Collections, Scientific Library PAU and PAN, KrakówJanusz Maria Brzeski

Janusz Maria Brzeski, photo: National Digital Archives

Janusz Maria Brzeski, photo: National Digital ArchivesIt’s extremely hard to place Janusz Maria Brzeski, Brzeski having been a graphic designer, draughtsman and photographer associated with the modernists, as well as an avant-garde filmmaker, art critic and journalist during his lifetime. However, his collages, steeped in French surrealism, stood out in his long artistic career. Through school and work on film sets, he was introduced to the idea of surrealism and began to experiment with it in his collage collection titled Sex, which was inspired by Sigmund Freud’s writings.

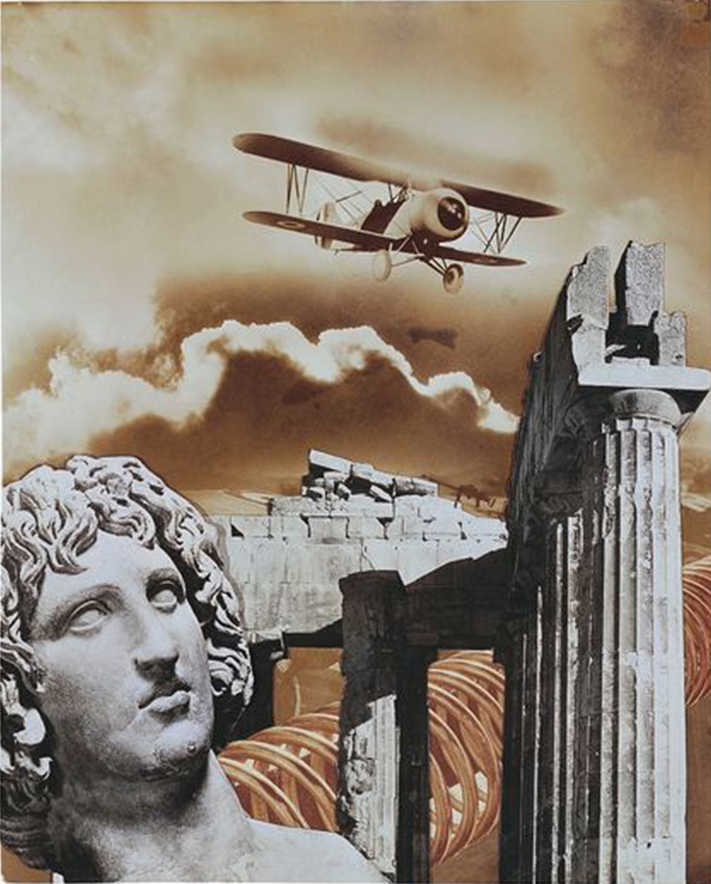

His collage work often brought in elements of sensationalist journalism to further his modernist aesthetics and ideas. For example, his series of photomontages Birth of a Robot, from 1934, combined eroticism with modern grotesque, tinted with constructivist aesthetics – together, they ask questions about the durability of the classical art traditions stemming from Ancient Greece. His legacy is a great example of the application of avant-garde methods to commercial press, oriented toward sensational coverage of the contemporary world. He was capable of blending high and low arts, becoming the harbinger of the international postmodern breakthrough of the 1980s and '90s.

'Two Civilizations' by Janusz Maria Brzeski, from the 'Birth of a Robot' series, 1933, photo: collection of the Art Museum in Łódź

'Two Civilizations' by Janusz Maria Brzeski, from the 'Birth of a Robot' series, 1933, photo: collection of the Art Museum in ŁódźKazimierz Podsadecki

Kazimierz Podsadecki, photo: National Digital Archives / www.audiovis.nac.gov.pl

Kazimierz Podsadecki, photo: National Digital Archives / www.audiovis.nac.gov.plHailing from the constructivist tradition, Kazimierz Podsadecki created photomontages along with his work as a painter and creator of applied graphic art. In 1923, he graduated from the Department of Decorative Arts of the Industrial School in Kraków. Afterwards, he became involved with the avant-garde periodical Zwrotnica (editor’s translation: Switch) and edited now-lost photoforms . In the weeklies Na Szerokim Świecie (editor’s translation: In the Wide World)and Światowid, he published photomontages that blended constructivist stylisation with surrealism. In 1933, the artist realised a series of collages entitled That’s My Illustrated Weekly Project where he created collages which focused on famous photographers and photojournalists. Towards the end of his career, he focused more on painting and his style gravitated more towards a colouristic convention.

Podsadecki was a visionary when it came to the art of collage. He would quote important modernist photographs and films, a technique not often seen in Polish constructivism and even European modernist art of the time, which programmatically didn’t make use of photographic quotations for fear of leading to eclecticism. However, Podsadecki saw this technique as innovative and continued to create what he saw as societally probing and interesting. A valiant effort indeed in a time where many artists refused to dabble outside of their assigned artistic movements.

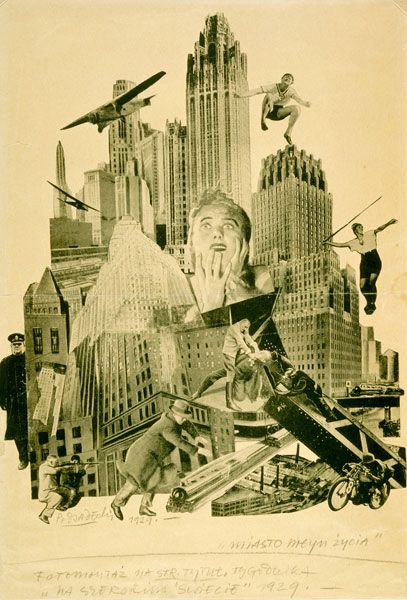

'City - The Mill of Life' by Kazimierz Podsadecki, photomontage, 1929, 43,5 x 29 cm, photo. Art Museum in Łódź

'City - The Mill of Life' by Kazimierz Podsadecki, photomontage, 1929, 43,5 x 29 cm, photo. Art Museum in Łódź