The extremely dry summer of 2015 left the queen of Polish rivers in miserable condition. In August the water level of the Vistula in Warsaw reached a record low of 50cm, which meant that many fragments of the otherwise wild and unpredictable river could be easily accessed on foot. It also meant that the river was now beginning to show what for many years and often centuries had remained submerged deep under water.

In the last months of summer 2015 receding waters revealed the wreck of a ship sunk during the Warsaw Uprising, elements of an old bridge burned at the end of the 18th century, and a train carriage used by the Germans to clear away the area of the Warsaw ghetto, as well as numerous stone pieces from a Jewish matzevot. While all these finds may be interesting in their own right and point toward different episodes in the complicated history of Poland and its capital city, some objects found in the river seem to tell a completely different and sensational story – one that starts like an Indiana Jones movie, and includes sensational finds in the library and a real archaeological treasure hunt...

Real adventure starts in the library

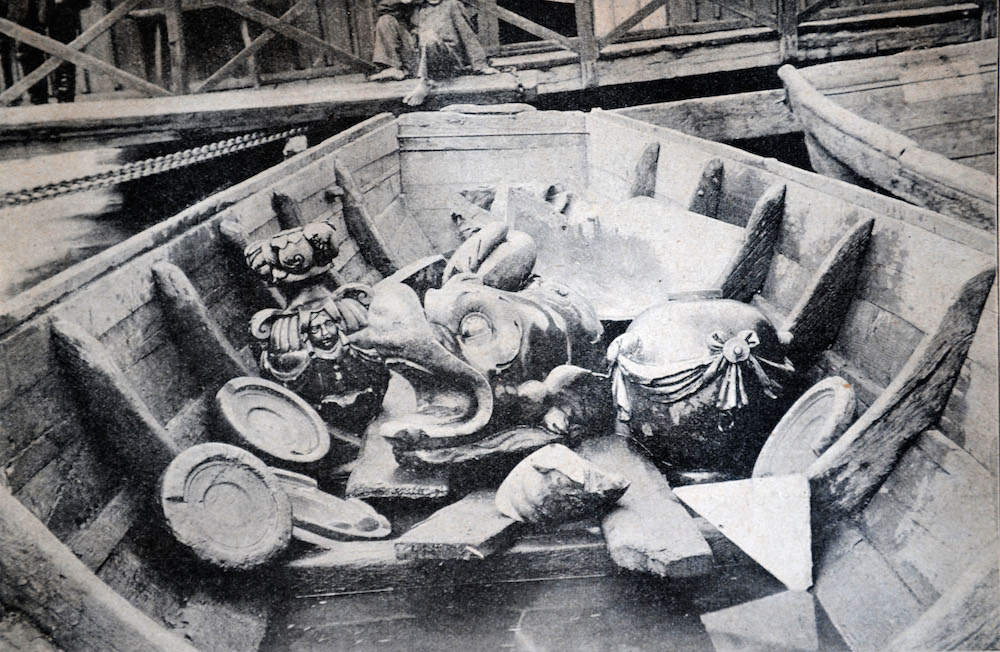

Elements found in the river in 1906, including the Dolphin - photographed for the local newspaper in 1906; photo: courtesy of Hubert Kowalski

Elements found in the river in 1906, including the Dolphin - photographed for the local newspaper in 1906; photo: courtesy of Hubert KowalskiIt starts in 2009 when Hubert Kowalski, a young archaeologist from Warsaw University, decided to delve deeper into what has become one of Warsaw's most intriguing urban legends. In the summer of 1906 newspapers in the capital seemed enthralled by the sensational news of a discovery made in the Vistula by local sand miners. According to the papers the sand miners retrieved several large marble sculptures out of the water, among them a beautiful Mannerist dolphin. The articles concluded with the information that the ropes broke when the workers were about to hoist a huge stone eagle – all they got was a broken wing.

Soon afterwards the Russian administration forbade any further search for treasures from the river. But even before that one of the leading experts on Warsaw of the time made the connection between these finds and the Swedish invasion of Poland in 1655, in particular the historical relations about the barges loaded with treasures looted from royal residences in Warsaw – according to historical sources one of the fully-loaded barges sank shortly after it embarked.

The problem was that neither the article, nor the earlier sources, mentioned where exactly on the river the treasure had sank. The investigation led Dr. Kowalski to another document, this time coming from after WWII, in which the son of one of the sand miners writes to the National Council for relief money. He backs up his claim by saying that his father was involved in the search for antique artefacts in the river – surprisingly he gives details of the exact location. This was a breakthrough. Kowalski now contacted people who could help, most importantly Marcin Jamkowski, a film maker and an experienced adventure photographer, and Konstanty Kulik, a film director. Together, and with the help of municipal river police, they now entered the river exactly where they thought they might find something.

The Treasure of the Vasas

Low water level in Vistula reveals elements of the Vasa residence in Warsaw, looted by the Swedes in 1656; photo: Marzena Hmielewicz/Adventure Pictures

Low water level in Vistula reveals elements of the Vasa residence in Warsaw, looted by the Swedes in 1656; photo: Marzena Hmielewicz/Adventure PicturesThe search started in 2010, with the water level high. Equipped with a whole array of the newest electronic technology devices such as sonar echo sounding and sub-bottom-profilers, the research team was able to “look” under the water and make a digital image of the riverbed. Still, that year they found nothing.

They returned next year with professional divers, which is not that great an advantage considering that, as Marcin Jamkowski explains, water visibility in the Vistula is around 10 centimetres.

Photo: Marcin Jamkowski/Adventure Pictures

Photo: Marcin Jamkowski/Adventure PicturesIn late summer 2011, when the water level was at waist level, Dr Hubert Kowalski tripped in the water and pulled out a piece of nicely worked marble with a beautifully engraved symbol.

'A Sheaf – the Vasa family crest!' he shouted to the rest of the team.

'At that point we had no doubt that what we were finding were artefacts from one of the royal residences dating from the reign of the kings of the Vasa dynasty,' Kowalski explains.

The royal emblem of the Vasa family (left); the Mannerist dolphin on a 20th century postcard; source: www.nimoz.pl

The royal emblem of the Vasa family (left); the Mannerist dolphin on a 20th century postcard; source: www.nimoz.plThis meant that they had hit the right spot. That same year they were able to pull out some 98 pieces of architecture: among them huge 700 kilogram lintels, arcs, and parapets. In 2012 the particularly heavy elements were raised by helicopters. That year also brought a beautiful fountain with mannerist masks of savage men. In 2015, when the river hit a record low, there were more finds – the most striking was beautifully sculpted cannons and a lot of cannonballs.

All in all, over the last five years the team was able to pull some 20 tons of Baroque architecture out of the water, most of it, as Dr Kowalski suggests, from the Villa Regia (Pałac Kazimierzowski), one of the many luxurious palaces of Warsaw plundered and looted by the Swedes in 1656. The elements were very likely removed, numbered, and packed on barges so that they could be transported to Sweden, just as so many other elements of Polish national heritage were.

– as Kowalski explains.

What happened in 1655?

Frgment of the panorama of Warsaw dating to the time of the Deluge by the Swedish artist Eric Dahlbergh. Villa Regia is circled red; source: Wikimedia/CC

Frgment of the panorama of Warsaw dating to the time of the Deluge by the Swedish artist Eric Dahlbergh. Villa Regia is circled red; source: Wikimedia/CCIn 1655 Poland became the scene of a Swedish-led military invasion, with important contributions from the allied armies of Brandenburg and Transylvania. For the next five years the country was systematically plundered and looted, leading to destruction that according to some researchers was more extensive than what Poland suffered in WW2.

According to historical sources the Swedish invaders completely destroyed 188 cities and towns, 81 castles, and 136 churches in Poland. Some towns and cities like Warsaw dropped in population by 90%, and they were also not actually rebuilt after the invasion. During this period the Commonwealth lost approximately one third of its population as well as its status as a super power. The massive and traumatic character of the invasion is reflected in the historical term used for it in Poland: the Deluge.

The deluge also left a mark on Polish cultural resources. The Swedes engaged in a massive and well-organized process of looting the cultural treasures of the Commonwealth. Polish palaces, mansions, and churches lost thousands of works of art, books, and riches which never returned to Poland.

From the Warsaw's Royal Castle alone, invaders took some 200 paintings, a few dozen carpets and Turkish tents, musical instruments, furniture, bronze sculptures, Chinese porcelain, weapons, textiles, books, and valuable manuscripts. A similar fate was dealt to other splendid palaces of Warsaw like the palaces of Kazanowski, Ossoliński, Daniłłowicz, and Ujazdowski Castle, the two royal palaces, and the residences of primates and bishops.

This was part of a larger strategy Sweden used across the whole 17th century. The wars fought across the Baltic (in Germany and Poland, but even as far south as Bohemia) were considered military expeditions which could bring not only great material wealth but cultural wealth as well. Large parts of the resources of the Uppsala library established in that period was made up of books looted by Swedish soldiers in Europe. After looting the city of Frauenburg (Frombork) in 1626 the Swedes took with them the book collection of Nicholas Copernicus (including an early edition of the De Revolutionibus) as well as the Cathedral library. These books, just as many other books important for Polish historical identity, including the earliest version of Bogurodzica (which is earliest religioust song in Polish lnguage) remain in Sweden to this day. In Kraków, which was also looted, Swedish soldiers destroyed the Altar of Saint Stanislaus, and looted his relics.

Wars with Sweden in the 17th century turned Poland into a cultural desert but for Sweden it was a good era, a period which established Sweden as the new power in Europe.

From Poland to Sweden

Hubert Kowalski and Marcin Jamkowski with Justyna Jasiewicz and one of their river finds; photo: Marzena Hmielewicz/Adventure Pictures

Hubert Kowalski and Marcin Jamkowski with Justyna Jasiewicz and one of their river finds; photo: Marzena Hmielewicz/Adventure PicturesThe great majority of the looted works of art, elements of architecture, and other riches made it safely to Sweden and have been there ever since. These works of art have entered Swedish royal collections and state museums. In the meantime, elements of architecture from Poland have become part of the Swedish cultural landscape, like the two bronze lions from Warsaw's Royal Castle which today stand near the Royal Residence in Stockholm.

“In Sweden one doesn't deny the origins of these elements and artefacts. It is well known that they come from Poland. Many of them have been incorporated in the architecture of various palaces, castles, and residences across Sweden. In virtually every Swedish city one can find something from Poland,” explains Dr Kowalski. “Of course, not everybody knows this,” he adds.

For the researchers and the film team, Sweden is the natural next step in telling the whole story.

“For us the elements we found in the Vistula are just a starting point from which we want to tell the story of the Deluge – but not only the story we know from this side of the Baltic. We want to go to Sweden and track down the elements that made it there, which the great majority of them did,” explains Kulik.

But as Kulik emphasizes, the film team is not interested in dealing with the issues concerning of restitution of these objects. “We are just trying to tell this chapter in the history of Europe.”

You can now watch the documentary Uratowane z potopu (Rescued from the Deluge) on Youtube.

Author: Mikołaj Gliński, 5th October, 2015; updated: March 2018