1. A competition of elite marksmen in traditional dress

The Marksmen (Bractwo Kurkowe) during annual parade in Cracow, 2011, photo: Grzegorz Kozakiewicz / Forum

The Marksmen (Bractwo Kurkowe) during annual parade in Cracow, 2011, photo: Grzegorz Kozakiewicz / ForumTo this day, there exists a little-known society in Kraków called The Marksmen (in Polish Bractwo Kurkowe). According to historians, it's as old as Kraków itself -- over 700 years old, dating back to 1257. Its main role was to protect the city. Thick walls, towers and gates by themselves weren't enough, so a special elite unit was trained.

Every year, seven days after Corpus Christi, a shooting competition would be organised to determine the Champion Marksman. Early on, live chickens and roosters were used as targets and this practice eventually evolved into shooting a wooden rooster figure, hence the choice of a rooster as their symbol. The competition is still organised to this day, and offers a real treat to onlookers since participants are dressed in the traditional feathered fur hats and velvet jackets of the Polish nobility of old. For more information, visit their website (in Polish, albeit with splendid images).

This shooting contest was once an important event for all of Kraków's artisans. Representatives of the different professions carrying flags of their respective trades took part in a parade that departed after a mass from St Mary's Basilica on the Main Square and reached the shooting-range. Those at the front of the parade were dressed in traditional Turkish, Persian and Tatars costumes and carried light rifles, singing as they walked. Next came the shooters and finally the Marksmen King with the Silver Rooster medalion hung around his neck. A gift from Sigismund Augustus, a 16th century king of Poland, today the Silver Rooster is part of the collection of the Historical Museum of Kraków. On some rare and special occasions, it is still presented outside of the museum.

[source: Jan Adamczewski, "Osobliwości Krakowa", published by Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, Warsaw 1986]

2. The imprint of a legendary queen's shoe

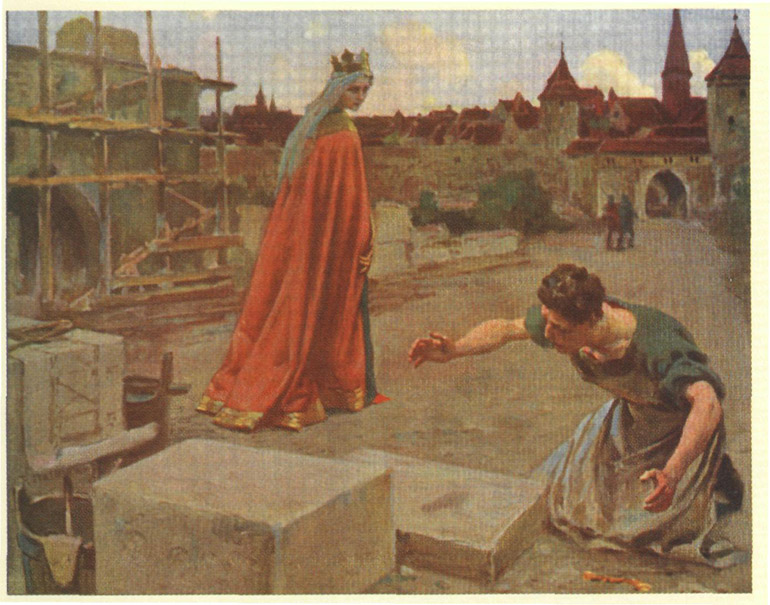

Postcrad about the story of the imprint of a legendary gueen's shoe, photo: CC / archive photo

Postcrad about the story of the imprint of a legendary gueen's shoe, photo: CC / archive photoQueen Jadwiga, daughter of Louis I of Hungary and Elizabeth of Bosnia, niece of Casimir the Great and first wife of Casimir Jagiellon, was an important figure in the history of Poland. There are many legends about her. It is said that in a journey outside the walls of Kraków, which she had undertaken to oversee the construction of the Carmelite Church she had funded, she engaged one of the workers in a conversation. The man told her about the sickness of his wife and their children, who he couldn't care for. The Queen not only gave orders to help the man but also wished to help him herself, so she gave him an expensive gift: the golden buckle of her shoe which she removed by pressing her foot against the damp sandstone from which the church was being built. To commerate the Queen's gesture, the stone worker paved around the spot on which her shoe left an imprint, creating a monument on the outside of the building. Later, an iron grid was installed to protect the imprint.

The imprint of a legendary gueen's shoe, photo: CC / Wikimedia / user: Ron Whisky

The imprint of a legendary gueen's shoe, photo: CC / Wikimedia / user: Ron WhiskyAfter the Queen's death, the commemorative stone became a place of pilgrimage, and can be found on the wall of the Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Kraków, at 19 Karmelicka st.

[source: Bronisław Heyduk, "Legends and Stories about Krakow", published by Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków 1972]

3. A soldier lying alongside a countess in catacombs

The Catacombs under the Church and Monastery of Reformed Franciscans, photo by Wojciech Kryński / Forum

The Catacombs under the Church and Monastery of Reformed Franciscans, photo by Wojciech Kryński / ForumBuilt in the 17th century, the Church and Monastery of the Reformed Franciscans is not one of Kraków's oldest. But Reformacka street, with its tall walls of the Monastery and its Station of the Cross painted by Michał Stachiewicz is one of the most beautiful nooks of Krakow.

For almost two hundred years, the catacombs underneath the Church and the Monastery served as a burial site. Over one thousand bodies lie here: those of monks, inhabitants of the city and members of important families. There are sarcophagi, crypts, coffins and bodies of monks lying directly on the sandy floor. The rare microclimate preserved the mummified corpses.

In 1812 a soldier in Napoleon's campaign who died in Kraków after the long march back from Moscow was buried here. Mysteriously, the unnamed soldier lies next to Countess Domicela Skalska, who after giving all her money to the monks, requested them to bury her next to the soldier.

The crypts are open to the public just once a year, on All Souls' Day (2 November).

[source: Jan Adamczewski, "Osobliwości Krakowa"

4. A murdered young girl in white haunting a mansion

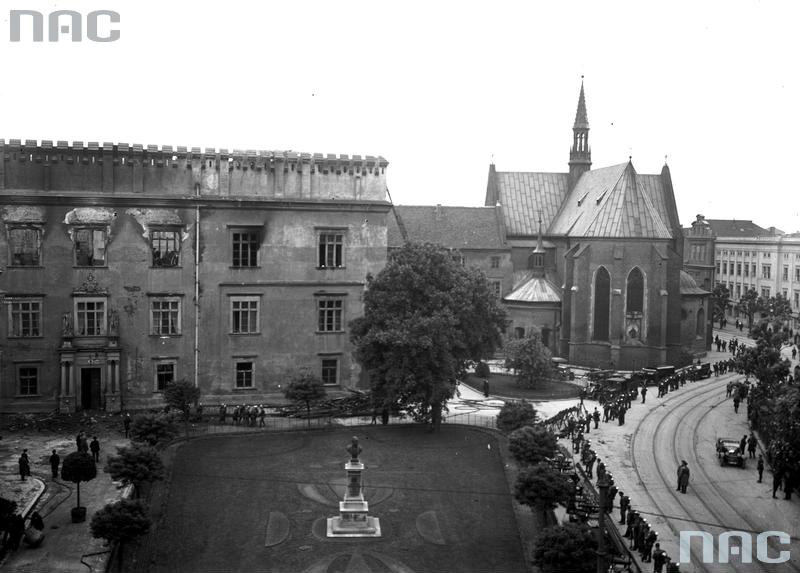

Mansion of the Wielkopolski family destroyed by the fire, photo: National Digital Archive / www.audiovis.nac.gov.pl

Mansion of the Wielkopolski family destroyed by the fire, photo: National Digital Archive / www.audiovis.nac.gov.plKraków's town hall is located in the mansion of the Wielkopolski family. The massive building is decorated with a crenellated parapet - now a rare sight in the city. Its date of erection is disputed. Over the years, it had various owners who expanded and redecorated it.

In 1850 a tragic fire took place which ruined it almost entirely. After a makeshift rebuilding of the burnt interiors, the building housed, among other things, an elegant café and a ballroom. In 1856, it was purchased by the Municipality of Kraków as headquarters for the Municipal Offices.

A strange and tragic story is associated with the mansion. Legend has it that two hundred years ago a priest from St. Mary's Church was called to perform the last rites for a dying person. The carriage that took him to the person in need purposefully drove around the dark streets of Kraków before reaching its destination. Once he arrived, the priest was taken to a chamber in which he found a body covered by a cloak. Two people entered the room: an old man and a young girl dressed in white. The priest was told to perform the rite on the girl. After it was done the mysterious body emerged from under the cloak. Dressed entirely in red, he turned out to be an executioner and beheaded the girl. The executioner and the priest were then offered red wine by the old man. The executioner drank it while the priest poured it over his shoulder. In the same bewildering manner the priest was driven back in the carriage, The next day he felt a burning on his back. It was the poisoned wine. Many years later, the priest found the Wielkopolski Mansion and informed about the events of that evening, but no one believed that the body of a young countess, punished by her father for a romantic affair with a butler, was secretly buried in the basement of the building. Since then the White Lady glides along the halls of the mansion.

[Source: Jan Adamczewski, "Osobliwości Krakowa"]

5. Minarets and a moon crescent among the Catholic churches

The minarets on Turkish House, photo source: www.lovekrakow.pl

The minarets on Turkish House, photo source: www.lovekrakow.plOn the corner of Długa and Pędzichów streets stands a town house called the Turkish House. It was erected in the late 19th century. It features three minarets, one of which ends with a moon crescent. The voice of the muezzin is nowhere to be heard, no one uses the minarets for prayer. All that remains are the slender towers.

Its Turkish architectural features are the work of its owners of the beginning of the 20th century. Veteran of the 1863 Uprising against the Russian Empire and officer of the Ottoman Army, the then owner Artur Teodor Rayski returned to Poland in 1890. In 1914 he joined the Legion of Piłsudski but, as a Turkish citizen, he was called to join the Turkish Army in their fight against the former during World War I. He took part in the naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign. He was promoted to Lieutenant rank and returned to Poland in 1919. Soon after he had to join another war - the Polish- Bolshevik war.

In the inter-war period he was head of the Aviation Department but his plans of modernising Polish aviation were interrupted in 1939. Despite his plea he was forbidden from taking part in the war. He traveled to Romania, France and England supervising the transportation of Polish gold to a safe location. Under the RAF he flew over North Africa and Asia. Following the death of General Sikorski he was named commander of the Polish Air Forces. After the war he never returned to Poland.

The heroism and strength of will of a man whom all called Commander long before he received the title will make the Turkish House a must-see for all history lovers.

[source: Bogusław Michalec, "Znasz taki? Kraków"]

6. A Jewish cemetary turned into a dumping ground by the Nazis

Remuh, photo by Marek Zern / Forum

Remuh, photo by Marek Zern / ForumIn 1533 the Jewish municipality Kazimierz (back then a separate city rather than a district of Kraków) bought a parchment of land between Szeroka and Jakuba streets and turned it into a graveyard. Twenty years later Izrael Isserles, an emigrant from Regensburg, banker for King Sigismund Augustus built a synagogue adjacent to the cemetery. After the wooden construction burnt down in 1572, it was replaced by a stone one. It was paid for by Rabbi Mosze Isserles and dedicated to his son whose name, Remuh, is used to designate the cemetery and synagogue.

Moses Isserles was an eminent Ashkenazic rabbi, talmudist, philosopher and educator. He is buried at the Remuh cemetery. Two hands carved into his grave indicate his heritage.

Austrian authorities ordered the closing of the cemetery in 1799. A new one was built next to Miodowa street. Most monuments vanished forever and the cemetery was abandoned. During the occupation, the Germans used it as a dumping site. The synagogue was also destroyed. In 1955 it was under investigation by archeologists. They found hundreds of Renaissance stone tombstones buried 60 cm deep in the ground. They were probably hidden there around 1704 when Kraków was invaded by the Swedish army. There were 47 tombstones before 1939 and over 700 were discovered. The oldest one is 430 years old and the youngest 270.

Their decorative elements remained intact. There are sandstone hands, grapes, leaf and flowers garlands, images of lions, eagles, deers, goats. But something else was discovered at Remuh: sarcophagi. They show the influence of Italian Renaissance on the cultural life of Kraków Jews. The reconstructed Remuh synagogue and the burial place of the Renaissance Jewish philosopher is a much visited place in the city.

7.The ancient hills of Kraków

Tadeusz Kościuszko Mound, photo by Stanisław Kocon / Forum

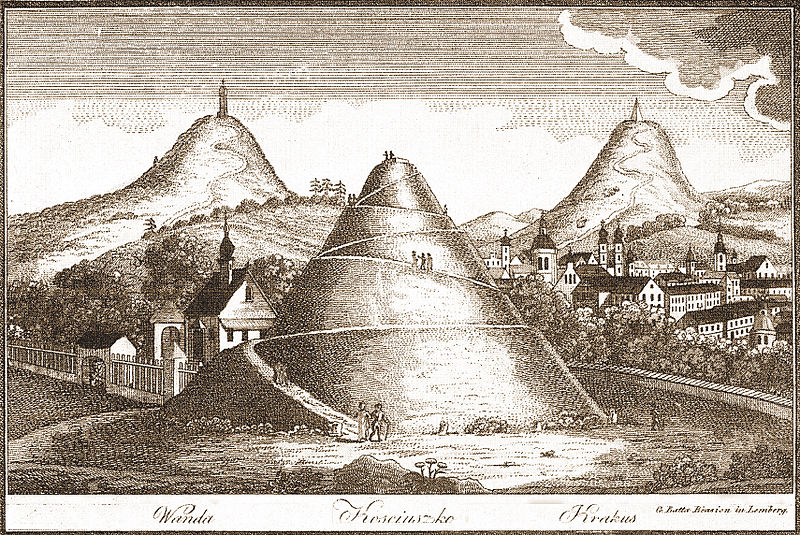

Tadeusz Kościuszko Mound, photo by Stanisław Kocon / ForumThere are four mounds in Kraków. Let us begin with the oldest, and the legends that are set around it. The Mound of the Krakus is located in the Podgórze district, in Krzemionki. It is 16 metres high and it was most likely heaped up in the 7th century – as seems to be indicatd by the bronze Avar jewel found in its interiors in the 1930s, during an archaeological excavation. The mound is considered a grave of the legendary founder of Kraków, Krakus. A huge oak used to grow on to p of the mound, and in the 16th century, the Lord’s Passion stood on top in the form of a cross .

Wanda’s Mound stands on guard of the borders of Kraków. It separates the housing area of Nowa Huta from the Lenin Metallurgic Plant (present day Tadeusz Sendzimir Plant). It is only 14 metres high, but it is also very old. The legendary name of this site is Wanda’s Tomb. Wanda was a ruling princess who rather than marry a German prince, threw herself into the currents of the Vistula river. This event also led to the naming of the village – Mogiła, meaning Tomb in Polish. It is the village that became a site for the buidling of Nowa Huta (The New Mill), Kraków's industrial district.

It is assumed that both of these mounds where sites which served the purposes of guarding and signaling. In older times, the peak of Wanda’s Mound was adorned with a stone statue which represented the heroine, with an engraving into the scaffolding that praised her actions. Unfortunately, the statue and the engraving gradually eroded. At present, a marble eagle designed by Jan Matejko crowns the mound.

Three of four Cracovian Mounds, archive drawing by Alexandr Glässer, 1740, photo: CC / Wikimedia

Three of four Cracovian Mounds, archive drawing by Alexandr Glässer, 1740, photo: CC / WikimediaThe third and the biggest of these is the 34-metre Tadeusz Kościuszko Mound, located on the mountain of St. Bronisława. It was raised over a period of three years, from 1820 till 1823. It is made with soil from the battlefield of Racławice, Maciejowice and Dubienka, as well as American soil – all collected from places where Kościuszko once fought. The soil from Maciejowice – a battleground which saw Kościuszko fall from his horse, heavily wounded – was transported in Vistual galley a by Countess Izabela Czartoryska. Between 1844-47 a road was built from Zwierzyniec to the top of the mound, and in 1862, the mound was crowned with a Tatra granite stone engraved with the dedication 'To Kościuszko'. In 1856, the Austrians surrounded the mound with fortifications.

The youngest mound in Kraków is the Józef Piłsudski Mound, located in the Wolski Forrest in Sowiniec. Its construction began in 1934, while the Marshall was still alive, and completed in 1939. In 1981, the Piłsudski Mound was included on the list of Kraków’s historic heritage sites.

There was once another, fifth mound in Kraków, in the Łobzowo area. People would say that it was the tomb of Esterka (literally little Esther), the Jewish beloved of king Casimir the Great. Those, who remembered the king said that it was not a big mound and it simply „melted”. No trace remains of it today. Apparently, it was simply flattened out and liquidated as part of the terrain’s preparation for a soccer field.

[Jan Adamczewski, "Osobliwości Krakowa”, The Pecularities of Kraków]

8. A breeze of Italy in the middle of Kraków

Gontyna Street, photo: CC / Wikimedia / user: Zygmunt Put

Gontyna Street, photo: CC / Wikimedia / user: Zygmunt PutThere is an unexpected yet delightful Italian accent in the gardens of the Salwator area: Gontyna, a small street which climbs up in an arch is surrounded by great villas with huge verandas and little towers. The gardens between the street and the houses are home to an almost Mediterrenean flora. Peace, quiet, and an impression that a breeze from the Adriatic cools the cheeks from beyond the roof line. Gontyna street is worth a detour as one strolls on the great Waszyngtona avenue from the tram stop on Salwator, en route to the Kościuszko Mound. The most beautifully located Salwatorski cemetery is also on the way there.

[Magdalena Kursa, Rafał Romanowski. "(KRK) Książka o Krakowie" A Book About Kraków, Znak, Kraków 2007]

9. A horse called Lajkonik parading through the city

Lajkonik, 2014, photo by Krzysztof Pawela / Forum

Lajkonik, 2014, photo by Krzysztof Pawela / ForumIn the begining was Lajkonik was only a legend, but who knows how much truth there is in legends? In 1287, the Tatars invaded Kraków once again. They besieged the hopeless city, and its dwellers were defending themselves in the high ramparts. Flisacy, a people which came from Zwierzyniec and made their living through sending wood downriver, came to the rescue of their beloved Kraków. They attacked the Tatars and killed their Khan. The Tatars ran away and the brave head of the Flisacy dressed up in the costume of the Tatar prince and he made a triumphant entry into the City, hearfully welcomed by the Cracovians.

Since then, in order to commemorate the heroic gesture of the Flisacy, eight days after the Corpus Christi holiday, the Lajkonik or Little Horse of Zwierzyniec makes a tour though Zwierzyniecka and Grodzka streets all the way to the Main Square, surrounded by a beautiful and colourful retinue. The Lajkonik dances arround, swaying a mace, and never fails to strike if he encounters a fair maiden – as this blow is supposed to bring luck in love. The parade takes place accompanied by music of the so-called mlaskoty. The head of the City welcomes the Tatar under the Town Hall Tower, and he presents him with a beaker of wine, which Lajkonik drinks in one gulp – for the well-being of Kraków and us all.

Lajkonik in 1933, photo: National Digital Archive / www.audiovis.nac.gov.pl

Lajkonik in 1933, photo: National Digital Archive / www.audiovis.nac.gov.plSome say that the Lajkonik custom is to be dated back to the 13th century and others, that it only started in 1559, when Poland began to celebrate Corpus Christi. But the very first record of the Little Horse of Zwierzyniec is from 1738. It was then that the Court of Kraków punished the Flisacy people for getting into a drunk fight as they were coming back from a Lajkonik procession.

In his book called "Pszczółka Krakowska”, Konstanty Majeranowski [1790–1851] shed some light onto the strange custom, thanks to the etchings of Michał Starowicz. As he created the atmosphere of an old legend around the custom, he made it into an almost national value – although Lajkonik has never appeared anywhere else on Polish territory outside of Kraków). The costume of Lajkonik was always oriental. The present-day costume was designed by Stanisław Wyspiański in 1904.

[Jan Adamczewski, "Osobliwości Krakowa”, The Peculiarities of Kraków]

10. A lantern for the victims of the plague

The lantern of the dead, near the church St. Nicolas, photo: CC / Wikimedia / user: Masur

The lantern of the dead, near the church St. Nicolas, photo: CC / Wikimedia / user: MasurNear the church St. Nicolas, on the Kopernik street side, there stands an interesting monument. It is a stone 'lantern of the dead'. These lanterns were raised in the Middle Ages, mostly in front of hospitals and the cemeteries, for those who died from the plague. A flame would burn inside the lantern to warn accidental by-passers. The lanterns were also raised in front of convents located outside of the cities. The last lantern of this kind was built the 14th century, and it once stood in front of the St. Valentine’s church in Kleparz. After the hospital and church were destroyed in the early 19th century, the lantern was relocated to the current Słowiański square, where it stood unitl 1871. Jan Librowski then moved it to a cemetery by the St. Nicolas church. It is a rare artefact and the reminder of a very old historic custom.

At least one historic event connected to this shrine deserves our attention. It is a surprising one, as well. On the 10th of November, 1910, Feliks Dzerzhinsky got married to the Polish communist activist Zofia Muszkat in this church. The witnesses of this ceremony were socialist activists, Emil Bobrowski and Sergiusz Bagocki, a friend of Lenin. Dzerzhinsky was then living on nr. 6 Kołłątaj street, which belonged to the St. Nicolas parrish, and thus the wedding took place in that church.

[Michał Rożek, "Przewodnik po zabytkach i kulturze Krakowa", A Guide to the Heritage and Culture of Kraków, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warsaw – Kraków 1997]

11. A former rubbish heap transformed into beautiful greenery

Explore the Planty Promenade, photo by Monika Oleksy / Forum

Explore the Planty Promenade, photo by Monika Oleksy / ForumPlanty are one of the peculiarities of Kraków, envied by all other Polish cities – a beautiful park which surrounds the Old Town with a ring of green. Many a story about Planty begins with the account that once upon a time, a great rummage began right beyond the city’s walls, with a muddy area filled with rubbish. And it was only the brave actions of the city activists which led to the creation of a public park around the City, a park which was called Plany. Because apparently, when they had to do was to plantować, i.e. to even out the mountains of garbage.

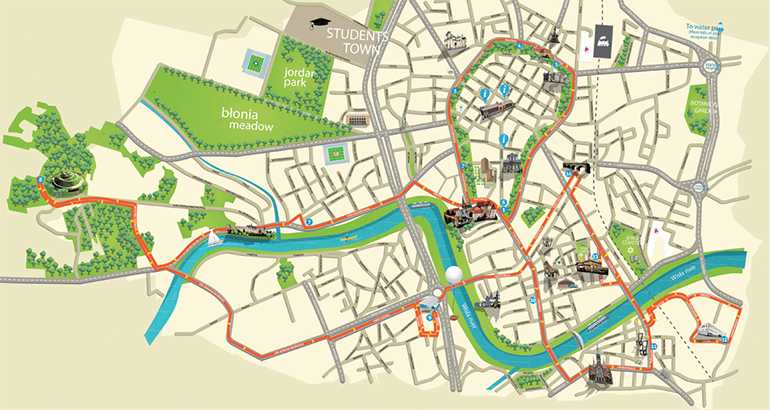

City map with Planty in the middle, photo source: www.cracowsightseeing.eu/

City map with Planty in the middle, photo source: www.cracowsightseeing.eu/After the city walls were dismantled, during the Kraków Republic period, authorities began to wonder what to do with those Planty. It must be admitted that when the walls disappeared, then City was filled with sun and wind, there was more space and light, and yet it seemed a bit bare…

In 1820, the head of the Senate, count Stanisław Wodzicki came up with a project according to which the City would become surrounded with gardens. The project was accepted and in 1822, the first ground works began. Two figures were especially important for the building of Planty – the professor and senator Feliks Radwański, and the continuator of his work, Florian Straszewski (who had even founded a capital of three thousand dukats and used to the percentage for the keeping of Planty.

In 1880, the magistrate took up the resolution to beautify the Planty with statues, an extra decorative element to the green corners. In 1884, two statues were raised – that of Lilia Weneda and that of Grażyna and Litawor. In 1886, there came two more – Queen Jadwiga and Jagiełło and the harp player and Bohdan Zaleski. In 1901, the statute of Artur Grottget was also raised, and that of Michał Bałucki came up in 1911. A pond with an island and house for swans was added to the Plany in 1904.

Planty in 1927, photo: National Digital Archive / www.audiovis.nac.gov.pl

Planty in 1927, photo: National Digital Archive / www.audiovis.nac.gov.plOne hundred years ago, on every weekend the Planty, much like the parks of Paris, were transformed into a public garden. All of Kraków played there. There were open air games, concerts, serendaes and illuminations which all made the stay in the city more pleasant. Planty were protected by special guards who watched over the benches so that the workers, drunks and badly dressed people would not stretch and lay across them. It was also 'forbidden for the benches to be taken up all kinds of maidens or public women in the afternoons, at a time when a more decent public is taking their walks'.

[Jan Adamczewski, "Osobliwości Krakowa"]

12. A monument for a dog

A monument of the dog Dżok, 2012, photo by Wojciech Strożek / Reporter / East News

A monument of the dog Dżok, 2012, photo by Wojciech Strożek / Reporter / East NewsThe story of Dżok the dog (pronounced Jock), albeit authentic, is growing to become another legend of Kraków. Dżok was a black-haired mix breed. His owned suffered from a heart attack near the Grunwaldzki roundabout, as a result of which he died. The dog would continually wait for his master in the same spot where the ambulance picked him up. The faithful four-legged creature moved people and won their sympathy. Intially, the dog was fed by the local people and suspicious towards strangers. After about a year of waiting, he allowed himself to be taken in by a new owner, a retired teacher named Maria Müller (a widow to a lecturer of the Kraków Agricultural Academy, professor Władysław Müller). The woman died in 1998. Made lonesome a second time, Dżok could not bear the passing away of his lady. After escaping from a dog shed, according to witnesses, the dog committed suicide by throwing himself under the train in Swoszowice. The most famous Polish dog now has a statue of his own.

Many organisations contributed to the raising of this statue. Among them is the Kraków Society for Animal Care, as well as Polish state media with headquarters in Kraków. Polish celebrities and Kraków locals also supported the cause, and they finally won over the intially unfriendly city officials.

A statue of Dżok the dog is located on Czerwieński Boulevard by the Vistula. It is near Wawel and the Grunwaldzki bridge. The statue was created by prof. Bronisław Chromy, who sculpted a dog that emerges out of open human hands. The sculpture symbolises canine faithfulness, but also the bond of man with animals. The official unveiling of the statue took place on the 26th of May 2001 with a German shepherd dog camed Kety doing the honours. At the time, it was the third statue of a dog in the world, after Edinburgh (Greyfriars Bobby) and Tokyo (Hachikō).

A sign on the Kraków monument (in Polish and English) reads: "Pies Dżok. Najwierniejszy z wiernych, symbol psiej wierności. Przez rok (1990–1991) oczekiwał na Rondzie Grunwaldzkim na swojego Pana, który w tym miejscu zmarł". / "Dżok, the dog. The most faithful canine friend, ever epitomising a dog's boundless devotion to his master. Throughout the entire year (1990–1991) Dżok was seen waiting in vain at the Rondo Grunwaldzkie roundabout to be fetched back by his master, who had passed away at the very site".

Two books were written about Dżok: Barbara Gawryluk’s "Dżok. Legenda o psiej wierności", Wydawnictwo Literatura, Łódź 2007 and Karol Kozłowski’s "Pies Dżok. Najwierniejszy z wiernych", Wydawnictwo Smyk, Kraków 2012.