In the autumn of 1860 he returned to Warsaw and soon after left with Kossak for Ukraine and Podolia. His first encounter with local nature and lifestyle had a tremendous impact on his future work and artistic interests. His fascination with Ukraine was clearly visible in the works with which he debuted at an exhibition organised by the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts in 1861. At first, he painted almost exclusively watercolours under Kossak’s supervision and in Kossak’s characteristic style.

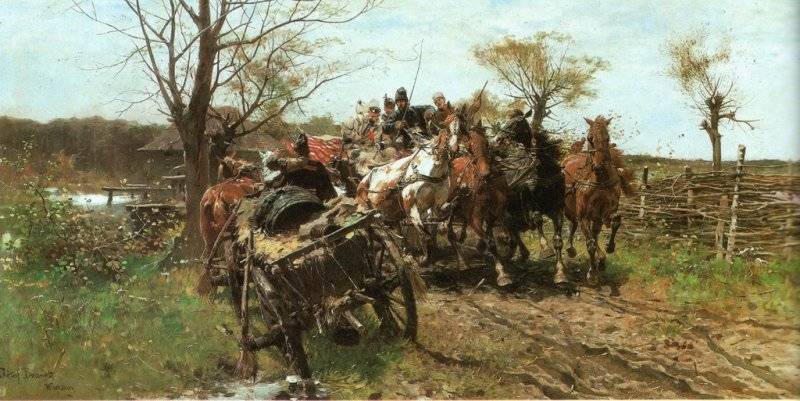

Meeting on a Bridge, 1884, oil on canvas, courtesy of National Museum in Kraków

Meeting on a Bridge, 1884, oil on canvas, courtesy of National Museum in KrakówIn 1862 Brandt left to study in Munich. He spent some time as an apprentice in Alexandr Strähuber’s workshop and later he attended composition class taught by Karl Piloty in the Academy of Fine Arts. Starting in May 1863 he worked in the atelier of Franz Adam, an outstanding military art painter, who played a vital role in shaping the young artist’s talent. For some time he was also a regular guest at Teodor Horschelt’s watercolour workshop, where he had a chance to familiarise himself with a huge collection of old weapons and military equipment, which proved to be of great help while painting historical military paintings. Due to Franz Adam’s support, he quickly found his place among artistic elite of Munich. Of course, his own skill played a vital role in his acceptance too. For example, his painting Chodkiewicz in the Battle of Khotyn, which was presented at Exposition Universelle de Paris in 1867, sparked an interest among French critics and public, and it was also well received by the German press.

Another example of his early acclaimed paintings is Return from Vienna – Rolling Stock, which was bought for the personal collection of Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I. The critical reception that he received and high interest from art collectors were important factors in his decision to stay permanently in Munich. Establishing his own workshop in 1870 elevated him to the title of the leader of the Polish artistic colony in the capital of Bavaria. He often helped young artists arriving in Munich, both artistically and financially.

In around 1875 he founded an informal art school in his atelier, where mostly young Poles learned the basics of painting. After marrying in 1877, he spent every summer in his wife Helena Pruszakowa’s estate in Orońsk near Radom. He also often visited Ukraine. The place was an inspiring one, as he often brought back numerous drawings and sketches, and also many historical artefacts, which after his death were to be inherited by the Polish nation.

Brandt reached his highest artistic form in the 1870s and 1880s. After the presentation of Battle of Vienna during the World’s Fair in 1873 he was awarded Order of Franz Joseph. In 1875 he was designated to be a member of Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin, and in 1878 he got a honorary professorship in the Bavarian Academy. Furthermore, in 1881, he was awarded the Order of Saint Michael. Brandt was among the social elite of Munich, and he was a friend of the prince regent Luitpold. The capstone of his career in Munich was 1892, when he received Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown. With that honour he was ennobled and received the title of Ritter. Even though his paintings were not quite on par with his earlier creations, his works were still extremely popular. Brandt himself also still enjoyed numerous honours.

In 1890 he became a member of the jury of the World’s Fair. He also received many more medals: the gold medal in 1891 in Berlin for The Song of Victory, the Order of Isabella the Catholic in 1893, and the Bavarian Order of Maximilian in 1898. In 1900 he became an honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Before that, in 1894, he was asked to replace the late Henryk Rodakowski as director of the School of Fine Arts in Kraków, but he did not accept the position. Although he was recognisable around the world, he did not forget about his homeland. He regularly sent his works to appear at various exhibitions organised in Poland, especially by the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, as he was a member from 1874, and the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts.

Czarniecki by Koldynga 1870, oil on canvas, collections of National Museum, Warsaw

Czarniecki by Koldynga 1870, oil on canvas, collections of National Museum, WarsawWith liveliness and a certain zest Brandt managed to resurrect the past of the Commonwealth on his canvas. Ideal knights in epic settings, Cossacks, Tatars, jaunty gentry, and brave hussars were all painted with the lush greenery of Ukraine and Podolia. But he didn’t only paint the military. Among other things, he portrayed everyday village life, marketplace scenes, and horses. He also created hunting scenes and genre paintings inspired by Ukrainian Dumkas, called Zaloty, By the Well or Cossack and a Girl. He also took inspiration from literature, from authors such as Wincenty Pol, Kajetan Suffczyński, and Bohdan Zaleski. He also highly valued the notebooks of Jan Chryzostom Pasek and Wojciech Dembołęcki. His first watercolour and oil paintings still show strong inspiration from his mentor and friend, Juliusz Kossak, such as similar horses, hunting scenes or battles and skirmishes. In these works, aside from stylistic inspirations, one can also see technical similarities to Kossak, such as strong contours, and pale, similar colours.

His artistic maturity starts to show as early as in 1863 in March of Lisowczycy or 1866’s Servant Leading a Horse During the Battle. They both show effortless and natural composition that includes complicated perspective devices in figures of horses and men, precise contouring and harmonious colour palette.

The capstone of his studies under Franz Adam is undoubtedly Chodkiewicz in the Battle of Khotyn. It’s an artistic memorial of the successful defence of Khotym against the Ottoman Empire in 1621, which foreshadows epic military scenes, such as Battle of Vienna from 1873 or Retaking of Jassyr (1878). In these vast horizontal scenes Brandt managed to create the illusion of battle noises, sudden emotions, and the dynamics of fighting people and running horses.

One of his best works strays away from this style. Czarniecki by Koldynga, painted in 1870, shows an episode of the Campaign of Jutland led by Stefan Czarniecki in 1658. It is different from his other paintings, because here we can feel a serious tone of contemplation. This time, the historical event isn’t the background for some effective anecdote, but rather inspires to purely artistic expression, which reveals itself in the simplicity, harmony, and discretion of this painting. In the central point of the painting we see some soldiers, trying to get from their ships to the snowy shore. Its gloomy nature is extremely important in this picture, at cloudy skies in a misty, damp atmosphere of winter dawn create an unwelcoming scene, which emphasises the difficulties this warband had to undertake.

Retaking of Jassyr, 1878, oil on canvas, collections of National Museum, Warsaw.

Retaking of Jassyr, 1878, oil on canvas, collections of National Museum, Warsaw.The ability to suggest acoustic experiences with the use of paint was characteristic to Brandt. This aspect of his paintings, undoubtedly stemming from his musical talent, is visible especially in paintings such as Greeting the Steppe (1874), which is often replicated and sometimes known as The Song of Victory; Mother of God from 1909, or Cossack’s Wedding, 1893, of which a few different versions were painted. All these pieces follow the same outline – a virtually unending steppe, under a clear, blue sky, a wedding procession, or triumphant cossacks/knights go down the road, singing, playing various instruments, and cheering. Banners and flags moved by the wind, windswept horse manes and guns being fired only strengthen acoustic effects that are a vital point in expressive nature of these paintings.

Beginning in the 1880s, Brandt moved away from monumental depictions of grand battles, and focused on smaller formats, which target smaller skirmishes fought by anonymous soldiers in smaller groups, or even lone riders (Alarm, painted around 1882; Capture with a Lariat from 1882; Skirmish with the Swedes; Battle for a Turkish Banner). Among his works from this period one can also frequently find images of lone riders with moving armies far in the background (for example, Swaggering, 1885; Hussar, 1890; Armoured Companion, 1890) and scenes from soldiers’ lives (Bow-hunting, 1885; Folding Banners, 1905; Return from Vienna 1890; Camp of Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1880).

These accessible paintings are rich with complex anecdotes and dynamic compositions. Thanks to this and certain artistic bravado they were very popular abroad, while in Poland they were a reminder of old, glorious Commonwealth and the temper of the Polish Sarmatians.

Another scene characteristic for Brandt is a picture of small groups of soldiers standing near a ford, about to cross the river or riding through a small, sleepy villages, or scouts covering vast emptiness of the steppe (Military Crossing, 1871; Layover in a Village; Cossack’s Recon, 1873; Crossing Carpathians, 1874; Crossing the Dnieper, 1875; Stakeout by the Dnieper, 1878). These works were where Brandt’s mastery in recreating landscapes came to light. The mutual elements of the scenery of these paintings, like bare, grassless ground, misty horizon and cloudy skies are the elements that create the atmosphere of melancholy, sadness, and exhaustion of a soldier’s life. These works instil a mood of contemplation and calm thanks to harmonious colours of doused greens, bronzes, greys and blues. These compositions unveil Brandt’s other side – a master of colour, sensitive to nature’s beauty. Virgin Mary of Pochayiv, also known as Virgin Mary of Armenia or Steppe Prayer (c. 1890) is one more piece connected with this kind of representation. It is said that this painting relates to the legend of a sacred picture of Mary that was held in an Armenian cathedral in Kamianets-Podilskyi and was later transported away out of fear of Turkish invasion.

Mary of Pochayiv c. 1890, oil on canvas, photo: T. Żółtowska-Huszcza, collections of the National Museum, Warsaw

Mary of Pochayiv c. 1890, oil on canvas, photo: T. Żółtowska-Huszcza, collections of the National Museum, WarsawThe anecdotal layer of this painting in overshadowed by very emotional connection of the artist to nature – the steppe, showered in moonlight, is very poetic, awakens feelings of longing, which interacts perfectly with people deep in prayer. His landscape painting technique, very impressionist, is quite different from his way of portraying characters, their raiment and equipment. The scenery is meant to capture fleeting feelings, isn’t meant to be precise, sometimes overly precise, as is the case with the characters.