New York, 1980s. The construction of affordable housing is suspended, the residents of ailing buildings are evicted, and the mental institutions are also shut down. The poorest and the sick become homeless, sometimes together with their entire families. Social services and welfare programmes are drastically cut down. Instead, a rapid development of a city for the rich is underway. This is how the effects of Reaganomics could be described in a nutshell. The era of capitalism in the United States began.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, an artist-designer, was a witness to this process, as during that time he was a lecturer at one of the New York’s universities. He moved from Canada, a welfare state, to East Village, which at the time was the most ruined part of Manhattan, crowded with beggars and homeless people sleeping on cardboard sheets or in abandoned buildings.

As a result of Reagan’s policies, about 100,000 homeless people appeared in New York, although official data indicated 75,000. I was surrounded by those people and immersed in the fumes of drugs sold in the unheated and half-ruined building in which I lived. I was also in contact with groups that helped the homeless, which is why, as a designer of industrial forms, I decided to act on it – the artist says in an interview with Culture.pl.

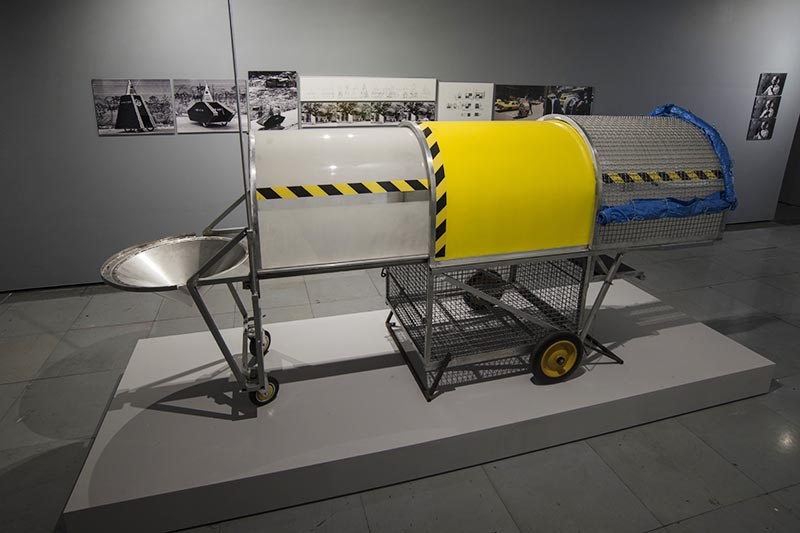

Wodiczko carried out a sequence of interviews with the New York’s homeless, learning about how they function by day and night in order to survive and protect their belongings. He was especially interested in those who collected glass, metal, and plastic for resale. Based on that, he designed the multi-functional Homeless Vehicle (1988-89) which reflected their real working and living conditions.

This vehicle is not a solution of the homeless crisis. It is an emergency tool for people who have no options, and an intellectual tool, as it articulates the complex situation of the homeless. It doesn’t represent them as garbage-collecting bums, but as people who use a device intended for specific purposes – which should not exist in a civilised world. This vehicle has a life-saving and didactic function, it finds a form for that which no one wants so know and see – the artist continues.

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Homeless Vehicle, 1988-1989, installation view at FACT in Liverpool, 2016, photo by Jon Barraclough

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Homeless Vehicle, 1988-1989, installation view at FACT in Liverpool, 2016, photo by Jon BarracloughIn this device, its user can wash, cook, rest, and sleep. He or she is able to safely store the collected bottles and cans. The inhabitant is also protected – the vehicle is visible enough to be safe from being smashed by, e.g. a reversing dustcart.

Such vehicle in the street provokes different questions. What is this part used for? How many of such vehicles are to be produced? Or: who are you? How did you become homeless? Then, that person is not only the demonstrator of the vehicle, but also a citizen of the city who has become homeless. That person works day and night, contributing to protecting the environment. He or she helps the city and should be paid for that – Wodiczko explains.

Both the Homeless Vehicle and a series of Instruments which Wodiczko designed in the 1990s – Mouthpiece (Porte Parole) (1993), Alien Staff (1991-94), and Aegis (1998) – are perverse tools which look like designs of a mad scientist, who wants to solve social issues through new technologies.

This, however, is not about solving individual problems, but about bringing out, exposing, manifesting the social needs which they respond to – Łukasz Musielak wrote in an essay accompanying Wodiczko’s retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Art in Łódź in 2015.

Wodiczko devised the method combining applied design with critical and ethical critique as part of his academic work, naming it ‘interrogative design’ or ‘scandalizing functionalism.’ Scandalising, because the existence of the problems whose solutions are put forward is an ethical scandal, and the apparatuses which he designs should not exist at all.

The utopian nature of this vehicle lies in hope that its function will eventually lead to its redundancy – the artist adds.

The prototype of Homeless Vehicle appeared in the streets, squares, and parks of New York and Philadelphia for two years. Its editions can be found in the collections of the MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków, Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon, and Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in DC.

Author: Agnieszka Sural, 30.11.2016, transl. AM, March 2017