The singer is a bona fide star on the international opera circuit today, a prime actor on major stages, critically acclaimed for his talents and with a name-recognition around which massive production are being built. And Kwiecień's schedule is reputedly booked until nearly the end of the decade.

He plays title roles in traditional repertoire – signature parts include Giovanni in the Mozart masterwork and Eugene Onegin, with which he opened the 2013 season at the Metropolitan Opera with conductor Valery Giergiev, in a production staged by innovative director Deborah Warner. And his efforts to bring less-recognized work to audiences – which in operatic parlance can mean less than a century old – have produced remarkable results. He’s taken on the role of Roger, the 12th-century king of Sicily whose multi-ethnic court and tolerant views fuel King Roger, the Karol Szymanowski opera that's being produced more frequently and more widely in our day than ever, nearly 90 years after its premiere in Warsaw. Which is due in significant measure to Kwiecień’s advocacy for the sultry three-act gem.

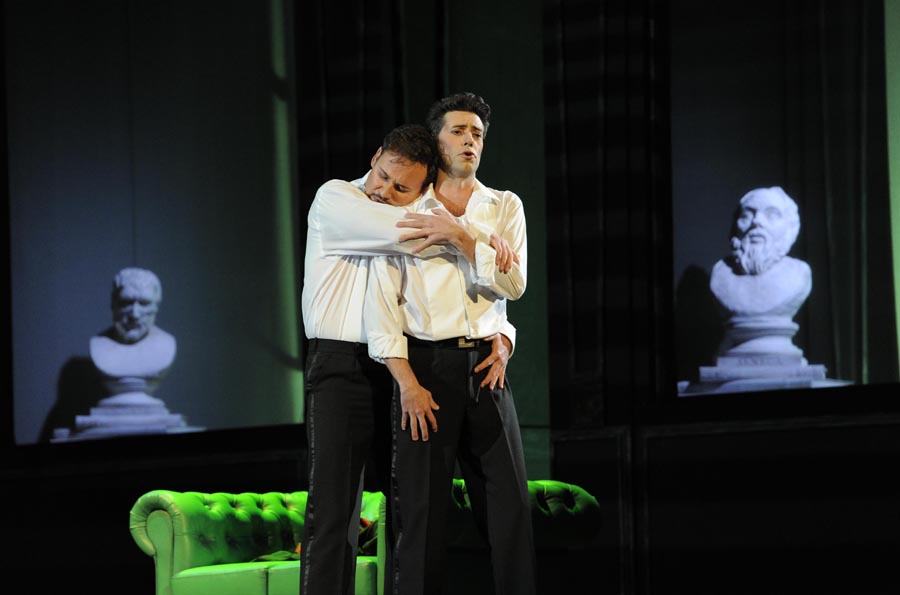

Michał Znaniecki's King Roger, Mariusz Kwiecień (Król Roger / King Roger) and Jose Luis Sola (Shepherd), photo: E.Moreno Esquibel / ABAO-OLBE

Michał Znaniecki's King Roger, Mariusz Kwiecień (Król Roger / King Roger) and Jose Luis Sola (Shepherd), photo: E.Moreno Esquibel / ABAO-OLBEKwiecień has gained his stature through persistence and exposure, like any great touring act – by “singing in front of audiences and impressing them”, as John Garratt of the independent web portal PopMatters put it in an admiring 2012 review of Slavic Heroes, Kwiecień’s solo CD. With his hard-earned, richly deserved position in place – with the opera world in the thrall of his lithe, hardworking skills – it remains to be seen how he evolves and branches out, as fellow baritone Thomas Hampson has with avant-garde recitals of George Crumb song cycles, or Renée Fleming’s jazz outings. Perhaps composers of new operas will gain his ear with fresh, compelling roles...

Early career, and international notice

After studies at the Warsaw Academy, Kwiecień began as a professional in 1993 in his hometown with the Kraków Opera, performing in Purcell’s Dido and Aneas in the latter role. The following year he won the Duszniki-Zdroj International Competition in Wrocław, and sang Figaro at the Teatr Wielki in Poznań and the Theatre Municipale in Luxembourg. He made his debut at the National Opera in Warsaw in 1996 in Stanisław Moniuszko’s sweetly comic Verbum nobile / The Word of a Nobleman, toured to Toronto in the composer’s Halka, and received the Vienna State Opera and Hamburg State Opera prizes in the Hans Gabor / Belvedere Competition.

Prizes for his Mozart readings and as Audience Choice came in Barcelona in 1998, and he represented Poland the following year at the Cardiff Singer of the World Competition. He also made his Met Opera debut, singing the role of Kuligin in Janácek’s Kát'a Kabanová, after participating in the Metropolitan Opera’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program.

While at the Met programme, he worked with the Head of Dramatic Studies, the director Stephen Wadsworth, who would be brought on board more than a decade later, in 2012, for the production of King Roger at the Santa Fe Opera – the first stateside triumph of that 80-minute hotbed of conflicting impulses and sumptuous royal yearnings. (Kwiecień’s co-star in that production, Erin Morley, had been with him in the Met programme.) In an interview at Dwutygodnik.com, Wadsworth – as renowned for work on the West End and Broadway as for opera productions at the Met and Covent Garden – said “Mariusz is like a tiger”, calling him “an actor who will go there”. Anticipating their complicated cast work on Szymanowski’s decidedly complicated opera, Wadsworth said he was “looking forward to a project where I know the conversations will be as sophisticated and complex as with any actors I can think of”.

With the second decade of his career underway in the early 2000s, Kwiecień was clearly on an international career trajectory. The critic Alex Ross, noting recent performances in October 2005 on his influential blog The Rest Is Noise (which gave the title to his award-winning book on 20th-century classical music), mentions:

Cosi fan tutte at the Met. In a fine cast, the standout was Mariusz Kwiecien, as Guglielmo. He has liquid legato, superb diction, charm to burn. Terfelesque” [a comparison to Bryn Terfel, the bass-baritone whose meteoric rise to fame occured in the early 1990s].

Giovanni takes to the Met

His debut in a title role at the Met in 2011, just as he turned 39, was highly anticipated. The company’s new Don Giovanni had been announced for the outset of Met season, the production conducted by Fabio Luisi – replacing James Levine as the company’s principal conductor – and directed by Michael Grandage, whose acclaim as chief of the Donmar Warehouse in London includes a Tony Award in 2010, for the production of John Logan’s Red, about the painter Mark Rothko. Kwiecień glowered appealingly in a light blue dress shirt on the cover of Opera News, the Met’s lavish monthly journal, the ruffles trim and the collar and cuffs seriously impressive.

That may seem ballast enough for a major premiere to set sail - but the Grandage production then took a rather operatic turn, with Kwiecień aggravating a disc he’d herniated on the Met’s summer tour to Japan with Puccini’s La Bohème. The injury struck at dress rehearsal, what’s more, in the last thrust of Giovanni’s first-act sword fight with the Commendatore. After surgery, and copious media attention, he embarked assertively on therapy while the production had its premiere and initial performances with Peter Mattei in the lead. (Which provided grist for the press mill of a rivalry, as Mattei, dynamic and acclaimed in his own right, was scheduled for his lead debut that season at La Scala in Milan – a stage with as great an importance as and a much deeper history than the Met.)

He was back for the fourth performance, impressively and rapidly rehabilitated and intent on the Saturday matinee show, which would transmit in the Met’s HD theatre broadcast to 44 countries and some 200,000 viewers – and Kwiecień wasn’t going to make that his first stab at the full show. He did the Tuesday performance, which sliced four days off his recovery time, in order to gel again with his colleagues in one of the grand, nasty roles in the opera canon. Kwiecień told the New York Times, which blogged about his surgery and then ran a feature on his recovery:

I am able to walk. I am able to clean my apartment. Why can’t I be onstage?

In one way of seeing things, his brief injury hiatus let reviewers – and opera reviewers are a fiercely special lot – unload on the Grandage production, which was in fact tedious. At that Saturday matinee, with the HD cameras sweeping low on their mechanized cranes, the set's tiers of balconies then the balconied facades behind them seemed to stand in for a compelling means of staging the familiar drama of serial seduction, abuse and the requisite not-happy ending. When hellfire flickered through the stageboards to end the opera and Giovanni’s earthly wrongs, it was about as hot as things got. (Grandage’s first opera had been mounted the year before at Glyndebourne.)

With Kwiecień, it was palpable that his focus was on his voice and projection – no flagrant leaps into the pit. For that is the priority in the Met’s immense auditorium, a prime example of size mattering in the U.S. with close to 4,000 seats, chandeliers that loft to the ceiling before the curtain goes up, and a volume that Kwiecień had already learned to illuminate with his lines.

The reviewer for Opera Brittania commended his “honeyed tone” as he attempts to persuade Zerlina of his charms – or, perhaps more precisely, of her willingness to betray or submit – and his “vocal wherewithal to deliver the explosive Champagne Aria”. The baritone’s interplay with his servant, Leporello (played by the daunting and tall bass-baritone Luca Pisaroni) was effective – it was “easy to see how they can deceive the rest of the cast when they swap identitites in Act II”.

Anthony Tommasini, lead critic for the New York Times, returned for a second review of the production – to focus on the lead performer. He was glad, as regards the Grandage production, to “put it out of mind” and concentrate on singing and the admirable orchestra performance of Mozart’s “multilayered, ingenious score”. The critic reckoned the baritone would need more time to fully recover his voice as well as his practiced agility, finding the former “patchy” in the extreme registers. He wrote of “the lyricism of his phrasing, especially in his upper range, notably in a silken rendition of Giovanni’s serenade to Donna Elvira’s maid” – which also gives a fair glimpse of Mozart's compulsive, indifferentiate character. Tommasini went on to specify the complex particularity with which Kwiecień occupies his vaunted roles:

During the opening scene, when he tries to seduce Donna Anna violiently, Mr. Kwiecien came across as wasted and desperately impulsive. In a later scene, when Giovanni, sensing the approach of a woman, asks Leperello to help him button his shirt and put on his nobleman’s coat, Mr. Kwiecien’s Don was obsessively fussy about looking just right. And during the final dinner scene in his home, surrounded by compliant young women, this Giovanni seems to know that the game is up […].

The role also provided Kwiecień his debut at the New National Theater in Tokyo. Then he starred in the fully staged version at the Disney Center with the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, their much-lauded thirtyish Venezualan musical director, and avant-fashion costumes by Rodarte.

No robes attached: Kwiecień on CD

Recent DVD releases reveal the latitude in his stage presence and his precise characterizations: Lucia di Lammermoor with the Met Opera, out on Deutsche Gramaphon in 2012, and the Bolshoi Opera’s production of Eugene Onegin on BelAirClassiques. (Releases from the World Opera Arias concerts at the courtyard of Kraków's Wawel Castle show him on home turf, in full recital bravura.) These recordings indicate the visual power of the opera form, at the lush summit of its contemporary achievements – though the viewer’s not in the same room, she or he gets the brunt of the medium, with its twin barrels of musical breadth and theatrical extravagance.

It’s another release from 2012, however, that accesses the crucial instrument pinioning Kwiecień’s abilities. In his four-star review of Slavic Heroes (Harmonia Mundi 2012), Guardian critic Tim Ashley notes surprise that, given Kwiecień’s high profile, it’s his first solo CD – then writes pertinently that the disc affords listeners the opportunity to focus on voice and delivery, what with the column space conventionally paid to Kwiecień’s acting and his winning demeanour (he's classified by catty opera mavens as a "barihunk"). Of the singer’s baritone, Ashley writes that “the basic sound – a mix of grit and velvet – is immensely appealing” then pinpoints Kwiecień’s interpretive dimensionality, highlighting:

a remarkable ability to colour his voice to suit each character, so that Borodin’s Prince Igor, thinking of his wife on the eve of battle, sounds very different from Rachmaninoff’s Byronic Aleko, teetering on the edge of self-destruction.

The track list comprises a welcome concentration for the international market on Central and Eastern European composers of the 19th and early 20th century – not exactly the voices of today, but not weighted toward Italianesque and Germanic dominance of the field. Dvorak’s “Prince’s Aria” comes from The Cunning Peasant, Smetana’s “Jen Jediana” from The Devil’s Wall, and an aria each is taken from Moniuszko’s Polish classics: Halka, The Haunted Manor, The Word of a Nobleman.

Kwiecień’s collaborators on the disc are Łukasz Borowicz, the superb young conductor, and the estimable Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra. And Slavic Heroes wraps up aptly with Roger’s closing, enthralling ode to the sun, the finale of Szymanowski’s King Roger – and a role that’s brought the singer to another level of acclaim, both in keeping and at a certain remove from his successes to date.

Roger – at home in the wastelands

The international revival of Szymanowski’s opera, King Roger, widened its momentum in 2012 when Kwiecień starred in the summertime production by the Santa Fe Opera. It's a revival that has flowed with incremental effectiveness that might be likened to the baritone’s own progress: two intriguing, varied Polish productions directed by Mariusz Treliński in 2000 and 2007, the Paris Opera production directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski that starred Kwiecień and that traveled to Madrid in 2011; the David Pountney production at the National Opera in Warsaw capping celebrations of Poland’s EU presidency in 2011.

Szymanowski composed the piece for years, after trips south from what's now Ukraine as far as Sicily and north Africa, in a phase when his music shimmered with "oriental" suggestions. The libretto was done with his cousin Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, and is ripe with homoerotic voltage couched in liberation existentialism. The opera that resulted – “daring and strange”, as critic Alex Ross has it in his book The Rest Is Noise – has a high point in the glorious Act 2 aria by Roxana (who'll leave her king for the Shepherd before that character's Dionysian exit). Szymanowski rewrote its third act into something of a murk – which may excuse King Roger's slow production history over the decades, or explain the current urges to stage it, or both.

While the European productions had brought new interpretations and reassessments – and disputes – about Szymanowski's opera, the SFO production would put it in front of audiences little familiar with the work or the composer. (King Roger has a scattered history in the U.S. – at Long Beach Opera in 1988, then a Bard College version directed by Lech Majewski that was neither easy to sit through nor well received.) It also put it in the travel plans of critics both across and outside the U.S. The SFO, after the Met Opera in New York City, stages the most new productions in the U.S.; each summer at their festival, their five new works can be attended during a reasonable desert stay. And their Szymanowski production came about because Kwiecień, an SFO favourite since playing Giovanni there in 2004 and Figaro in 2008 (he's exhibited his Santa Fe photos in Kraków), had been invited by Charles MacKay, the general director, to suggest new productions for the company. When he chose King Roger, myriad wheels began to turn.

Though the opera had been little seen in the States, recent international activity was being tracked. In the Wall Street Journal, Jonathan Blitzer wrote of “Szymanowski’s enchanting if sometimes befuddling masterpiece” after attending Warlikowski's production in Madrid, where he found Kwiecień and Ukrainian soprano Olga Pasichnyk “mesmerizing complements”. In a video interview on the SFO site, Kwiecień says “the staging was really controversial, but it was in my opinion great” – and that Warlikowski's conception received boos in Paris and Madrid, and a “huge ovation for the singers and the music” under conductor Paul Daniel in Madrid.

He speaks also in that clip of the relation of his instrument to a role in which allurements and anxieties having their way with Roger keep him front and center for three acts. “I was never interested to sing this opera”, the baritone says of his earlier career, “because this is written for rather heavier voices, heavier baritone, lyric, but full lyric voice, because of the orchestration, which is very thick, very rich”. And he cannily places it in his career trajectory, which now includes the role:

King Roger is a niche opera. It’s not a thing which I can really make a breakthrough. So Don Giovanni, Onegin, Lucia di Lammermoor, Don Carlo – this is the repertory which is really important to sing and exist as an opera singer, like I do now. And now, having my position, I can really present King Roger […]

He terms the piece “in my opinion the best Polish opera work done ever”, and adds that “I don’t know any other opera in which you can really have such a strange point of – such a huge variety of possibilities to make it, to play it”.

The SFO supplemented their orchestral and choral forces to achieve Szymanowski's vibrant sound, and drew full houses to their exceptional 2,100-seat open-air house for the wild-card production of a festival that included Rossini, Puccini and Bizet. The Times critic Tommasini found the opera “mystical, sumptuous and daring”, then wrote “It is hard to imagine that the Santa Fe Opera would have presented ‘King Roger,’ had it not lined up the dynamic Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien to sing the title role”. He also gave another take on the question of priority:

Though an intense and alluring Giovanni, Mr. Kwiecien has lots of competition. But he owns the role of King Roger, which he first sang with the Paris National Opera in 2009. I missed that production, but reviews and videos give the impression of a wild, modern, erotic interpretation.

In the Washington Post, Phillip Kennicott wrote of “the absolute, thrilling commitment of baritone Mariusz Kwiecien”. (Kennicott also pays just tribute to the composer as “one of the greatest orchestrators of his day, eliciting from the orchestra novel sounds that even today will make close listeners do a double take”.) In the Santa Fe Reporter, the local critic, John Stege, commended conductor Evan Rogister (tapped by Opera News as one of its rising stars) then went to the heart of the production:

But ultimately, it’s Kwiecien’s show. A peculiar musical marking, molto ansioso, occurs more than once in the score and offers a key to Kwiecien’s posture nearly throughout. Anxious, fearful, incomplete, restless, he roams the stage like a desperate creature. I can’t think of a contemporary singer who more totally inhabits a role in such powerful physical, emotional and vocal terms.

Late in 2012, Kwiecień starred in the role again in Bilbao, in Michał Znaniecki's production, for which Kwiecień was awarded the Premios Liricos Teatro Campoamor for best opera singer of the season in Spain.

More Met, and more to come

It had been in Eugene Onegin that Kwiecień made his lead-role debut at the Bolshoi in Moscow, prodding at life and teasing at love opposite Ekaterina Shcherbachenko – lauded as the Cardiff Singer of the World at the annual competition in 2009. The production, directed by Dmitri Tcherniakov, toured to the Paris Opera and to Covent Garden in 2009 (where the critic from Theartsdesk.com found the alternate baritone who played Onegin on the night under review “nowhere near as charismatic or as good an actor as Mariusz Kwiecien”) and to Teatro Real in Madrid.

He also sang Onegin for his most seasoned admirers in June 2013 – the audience at the Kraków Opera. And his latest major role is in the Met’s new production of Tchaikovsky’s opera, conducted by Valery Gergiev and staged by Deborah Warner – plus, complicatedly, Fiona Shaw.

Met director Peter Gelb has been engaging renowned theatre directors in a bid to clarify storytelling of the genre that is famous – and often unwieldy – for codifying the major performing disciplines into a “total” form. Successes in the Met director chair thus far include Bartlett Sher, though misses include Michael Grandage – and, as reviews would have it, the Warner-Shaw Onegin.

Mariusz Kwiecien as 'Eugene Onegin', Metropolitan Opera, 2013, photo: Ken Howard / Metropolitan Opera

Mariusz Kwiecien as 'Eugene Onegin', Metropolitan Opera, 2013, photo: Ken Howard / Metropolitan OperaTchaikovsky finished his piece in 1878, adapting the novel in verse by Pushkin tracking thwarted couples and heedless aristocrats – those serial breeders of operatic intensity. It’s setting has been updated by Warner from the early 19th century of the novel to Tchaikovsky's era. A co-production with the English National Opera, it was chosen to open the Met’s 2013 season – and got hit with another case of opera within the opera. Warner, acclaimed for intelligent interpretations and for challenging the conventions (eyes peeled if she gains rights for the all-female Waiting for Godot she’s been eager to direct), required surgery as the production gathered steam.

She turned the production over to Fiona Shaw, who is a director in addition to her renown as an actor. But Shaw was simultaneously directing a Britten production for the Glyndebourne Festival, was not at rehearsals for the final two weeks, and could not attend the gala opening night on the 23rd of September.

The premiere screened on huge videos in the plaza of Lincoln Center, the Met’s home near one corner of Central Park in Manhattan, and in Times Square. Co-starring with Kwiecień is Anna Netrebko, among the stellar sopranos of our time, who came to her role fully primed, having played Tatiana at the Vienna Opera in spring 2013. The Times found him “appealing” as the haughty aristocrat, his voice “dark and virile”, his singing “volatile and exciting”. In the Washington Post, lead critic Anne Midgette said Kwiecień is “convincingly youthful and compact as Onegin, with a sound more pliable than is his wont”.

This Onegin proved a sweeping success for another co-star, the tenor Piotr Beczała, as Lenski, Olga’s fiancé and fated to be dueled to death by the title character, his ex-friend. The tenor – even with nothing to do once Act 2 ends in pistols, received forceful praise – a “bright, ringing voice” said the Times, while New Yorker magazine found that with his “blazing voice”, Beczała “ran away with the show”.

Mariusz Kwiecień, meanwhile, was on to his next set of adoring, demanding houses. Late 2013 was packed with dates at the Paris Opera as Riccardo in Bellini’s bel canto tour-de-force I puritani, a role he played at the Met in April and May 2014. Then he nimbly resuscitated Giovanni and repeated that eternal descent to join the damned at Covent Garden through February 2014, in the Royal Opera’s production directed by Kasper Holten.

In 2011, he was recognized as the best opera singer of the season by the representatives of the Spanish music market and was awarded for the performance of Szymanowski’s King Roger at the Teatro Real in Madrid. In 2017, a DVD recording of King Roger directed by Kasper Holten with Mariusz Kwiecień in the title role was nominated for Grammy award in the Best Opera Recording category. A year later, a recording of Les Pêcheurs de Perles from the Metropolitan Opera was nominated in the same category.

Perhaps it’s at the website of the National Opera in Warsaw that his accomplishment – and his audience-based approach – was put most succinctly, for the moment. In reference to the homecoming recital he performed there in June 2014 with Decca-recording artist Aleksandra Kurzak, they had just two words: “No tickets”.

Discography

CD:

- A Night At The Opera - 2001

- Bel Canto Spectacular - 2008

- Brahms: Ein deutches Requiem - 2008

- Chopin Songs - 2010

- Slavic Heroes - 2012

DVD/Blue-Ray:

- Lucia di Lammermoor - 2009

- Eugene Onegin - 2009, 2014

- Don Pasquale - 2011

- Mozart: Don Giovanni - 2014

- Szymanowski: Król Roger - 2015

- Bizet: Les pêcheurs de perles - 2017

- Dionizetti: La Favorite - 2017

- Puccini: La Bohème - 2017

Website of the artist: www.mariuszkwiecien.com

09.12.2013 Sources: Columbia Artists Mangagement Inc. (www.cami.com), www.popmatters.com, Dwutygodnik.com, Santafeopera.org; updated by MG, March 2019.