Anna Arno, a biographer of Gałczyński, states that Galczyński’s addiction to alcohol was characterised by periods of hard-core and dangerous binges interspersed with long months of complete abstinence from alcohol as well. The memory of the poet’s friends suggest that his drinking binges were terrifying. He suffered a lot and he was aggressive and difficult to calm down. However, between these bauches he was capable of refusing a drink, always to the surprise of those close to him.

He must have visited Anna Kowalska on one of his debauches, as she recalls his monologues as a “bredouillement d'ivoigne” (drunk gibberish). At times, his writing was murky.

A Poet of Marriage

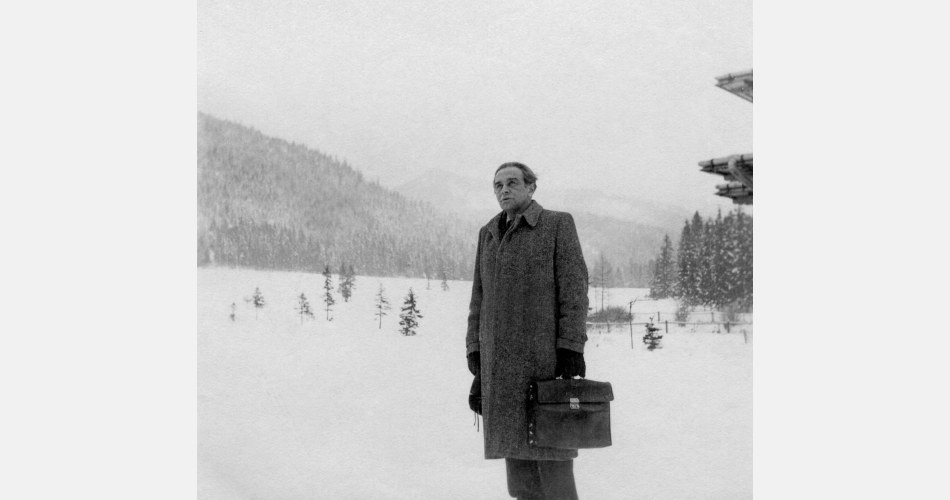

Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński with his wife Natalia in the forest lodge Pranie, early 1950s, photo courtesy of: FoKa / Forum

Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński with his wife Natalia in the forest lodge Pranie, early 1950s, photo courtesy of: FoKa / ForumThe Green Konstanty and the Silver Natalia – such are the first associations that pop into our minds when we think of Gałczyński’s poetry. Gałczyński devoted uncounted poems to his spouse, rhyming her glimmering eyes, silver hips and caucasian walk in myriad ways. The couple married on June 1st, 1930, when Konstanty was 25 and Natalia 22. Yet there are those, such as Józef Łobodowski, remarked that his poems about Natalia are barely sensual, with an erotics closer to Plato than to Catullus or Bocaccio.

Some have complained that he wrote about his wife, for his wife, and for their anniverasaries. These poems also constitute the better known Gałczyński, the more popular of his faces, with quotes that still often adorn wedding inviatations. Gałczyński is the popular poet thanks to his marital verse. According to Anna Arno, he made the theme of fulfilled, domestic love, a love that persists among everday accessories and kitchen scents, into his specialty.

A Poet of Extramarital Love

This angelic picture of family happiness and a faithful love is contradicted by the war-time period in the poet’s life. Gałczyński spent most of this time in the POW camp in Altengrabow by Magdeburg. He had affairs with three women at the time, and it seems that he wanted to marry each of them. Between 1945 and 1946 he proposed - almost simultaneously - to Lucyna Wolanowska, who had just been freed from Auschwitz and who gave birth to his son, as well as to the young poet Maruta Stobiecka and to Nela Micińska. If we add to these three a Venetian beauty to the camp that fascinated Gałczyński (he wrote the Na śmierć Esteriny or To the Death of Esterina poem in her honour), we get a picture of both emotional luxury and confusion.

After the camp’s liberation, Gałczyński didn’t return to Poland for a long period of time, most likely due to this confused situation. He went further than that - he did not give any sign of life, and even deliberately did not clear up rumours of his death. There were farewell articles released in the Polish press, authored by Jerzy Turowicz and Tadeusz Wittlin. Gałczyński described the complicated state of his spirit in the text entitled Notatki z nieudanych rekolekcji paryskich (Notes from the failed Parisian retreat). He returned to Poland and to his wife in 1946, only then to return to Kraków with one of his lovers, Maruta Stobiecka. A few days after their arrival, Jan Dobraczyński took Stobiecka to Warsaw and put her in... a convent. Only a few weeks after Gałczyński wrote a poem for her, declaring he had to go astray in order to finally comprehend she was the meadow, the tree, the moon and the leaf.

The scattered poet and fiancee soon became the inspiration for the figure of Hermenegilda Kociubińska, one of thee Green Goose Theatre characters.

The Popular Poet

Irena Kwiatkowska as Hermenegilda Kociubińska in the Zaczarowana Hermenegilda performance from 1975 , source: NAC

Irena Kwiatkowska as Hermenegilda Kociubińska in the Zaczarowana Hermenegilda performance from 1975 , source: NACIn Kraków, the poet began his intense collaboration with the Przekrój magazine. He published lyrical works with Przekrój, but most notably, in a regular column of the weekly, he created the pure-nonsens Green Goose Theatre and Letters with a Violet. These entries were what really won him his fame. In the Green Goose, Gałczyński created a gallery of colourful characters. There is Piekielny Piotruś (The Infernal Peter), an honest young man Alojzy Gżegżółka, the dog Fafik, faithful to the Green Goose, the master of morals, donkey Osiołek Porfirion, and angelogist Professor Bączyński, and the aforementioned Hermenegilda Kociubińska. Irena Kwiatkowska, an iconic Polish actress regularly imperosonated Hermenegilda in her performances with the Seven Cats’ cabaret.

The Communist Poet

Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński's apartment in Warsaw, 1950s, photo: Muzeum Literatury / East News

Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński's apartment in Warsaw, 1950s, photo: Muzeum Literatury / East NewsThe Green Goose period came to an end with the so-called Gałczyński affair. In June 1950, at a state literary meeting, Adam Ważyk accused his work of a petty burgeoisie spirit and summoned him to "twist the head of the little canary bird that made his home in the verses". In turn, but unofficially, the poet responded that the canary bird could be killed, but then the birdcage would come to the fore. "What do we do about the cage, my friends?" he asked.

Gałczyński was forced to propose a self-critique, and he took this experience very hard. Riding the wave of adapting to socialist poetics, he even wrote Poemat dla zdrajcy (Poem for the Traitor), dedicated to Czesław Miłosz. In 1951, Miłosz asked for political asylum in France, and he later portrayed Gałczyński as Delta in his Captive Mind.

But what was Gałczyński’s true stance towards communism?

Anna Arno has found a sketch of a poem, wherein he marked a line across the page and at the bottom, he added, “And all this thanks to the Red Army.” Gałczyński preferred writing about the charms of everyday life, and falsely added it was thanks to the Red Army.

He was capable of writing well even when the topic was commissioned. This was the case with a poem after Stalin’s death, included in an anthology with other poems about the soviet leader’s passing. Gałczyński’s verse stood out against all others, in the words of Konstanty Jeleński, due to his “owning the Midas’ secret of transforming each and every imposed topic into poetry.” During the communist era, however, this effortlessness of writing was also a curse.

Rent-a-Poet

Gałczyński apparently told Tadeusz Kwiatkowski in conversation,

“ I would write in honour of the Queen Hedwige’s dog.” “Perhaps she didn’t have a dog?” “What do you know. She did. His name was Incydeusz. And if she didn’t, I would write about her foot. Have you seen the trace of her foot on the Carmelites’ Church? It deserves a poem in octaves.”

Gałczyński always wrote on demand: poetry was his life and his means of living (he only had one other job in his life, at a diplomatic post in Berlin in the 1930s). He was able to negotiate and remind others about his pay, and during the period of collaboration with Przekrój, at the height of popularity of the Green Goose Theatre, he earned a very comfortable living. Gałczyński was fully aware of his dependance on the sponsor, writing “well, I do have a job in this company / of falsehood, iron and paper.” It is the desire to make money that best explains his pre-war collaboration with Prosto z mostu. He was not only ready to write on any subject but also in any... size.

Apparently, when Janina Ipohorska requested a piece “5 centimeters high and 5,2 cm wide,” one that would fill up a hole in the layout of one Przekrój page, he took the demand seriously. According to Jerzy Waldorff, after 15 minutes, a poem of this exact size was ready.

The Craftsman of Verse

Anna Arno states that the initial ideal of “making” in the poetic matter was inscribed by Gałczyński into a socialist propaganda of work. He considered himself someone like Wit Stwosz, a poem about whom turned the medival sculptor into a hero of modest work, someone of great persistence and a higher fidelity of 1952…

The Misunderstood Poet

Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, 1940s, photo: Muzeum Literatury / East News

Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, 1940s, photo: Muzeum Literatury / East NewsGałczyński is indeed a phenomenon. He is at once easy and difficult. Even the popular Green Goose divided audiences and critics and received criticism of contradictory faults. In a summary of Gałczyński’s oeuvre, Tadeusz Stefańczyk wrote:

The reader was presented with a meticulous buffoonade, a surrealist theatre of meanings, allusions and suggestions that mutually erased each other, and created a colourful chaos in the mind. A kind of ethereal mess, that a most trained critique could not put in order for years. One can evoke the ongoing polemic between Sandauer and Stawer, around pieces such as Kolczyki Izoldy (Isolde’s Earrings) and the Skumbria w tomacie (Scumbria in Tomato).

Sandauer stated that in reading Gałczyński’s work, what should be taken seriously are not his serious statements but those cheeky winks which he generously scattered across his works. Leopold Staff, many years his senior, wrote a little poem about the author:

Pokazałeś w wesołej herezji

Przez swe fraszki fiołkowe i gęsie,

Ile jest nonsensu w poezji

Ile poezji w nonsensie.

Which could translate as:

You showed in a happy heresy

Through your violet trifles and geese

How much nonsense there is in poetry

And how much poetry in the nonsense

(translation by Paulina Schlosser)

Author: Mikołąj Gliński, 6.12.2013, translated with edits by Paulina Schlosser, 12.12.2013