Photographs of Piłsudski’s brain feature in the large exhibition entitled Progress and Hygiene at Warsaw’s Zachęta National Gallery of Art, which will run till 15 February. Curated by Anda Rottenberg (undoubtedly one of the most important characters of the current Polish art scene), the show is devoted to the pitfalls of 20th-century modernization, with its idealistic faith in progress and possibilities of improving both man and society. The exhibition questions the topicality of genetic engineering, eugenics, racial purity research and such in the societies of today. But how does Piłsudski’s brain fit into this picture?

The Marshal’s Brain

Józef Piłsudski in his coffin in St. Leonard's crypt of the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków; source: National Digital Archives / www.audiovis.nac.gov.pl

Józef Piłsudski in his coffin in St. Leonard's crypt of the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków; source: National Digital Archives / www.audiovis.nac.gov.plJózef Piłsudski died on May 12, 1935, in Warsaw. Shortly after his death, his brain was removed and handed over to scientists from the Polish Institute of Brain Research in Vilnius. The institute, which had been established in 1928, was run by Professor Maksymilian Rose, one of the leading neuroanatomists of the time and an expert on cytoarchitecture. Born in 1883 in Przemyśl, Rose had studied in Switzerland and Germany and had only recently turned to the new and fashionable branch of neuroanatomy, devoted to the research of the so-called "elite brains". This kind of research was popular in Europe in the first decades of the 20th century, with major research institutes cropping up all over Europe, for example the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Hirnforschung in Berlin, the Instituto Cajal in Madrid or the Institut Mozga in Moscow (famous for performing research on Vladimir Lenin’s brain).

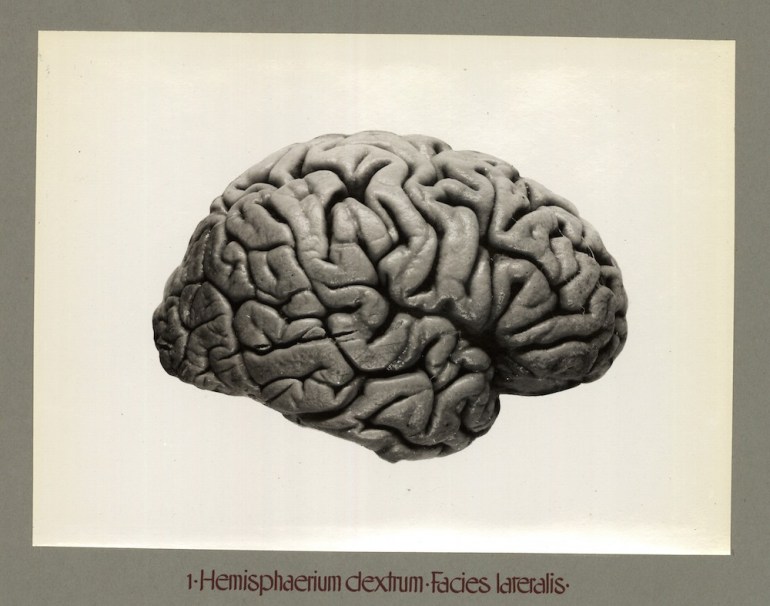

Piłsudski's brain - right hemisphere, lateral part; source: Mózg Piłsudskiego at Polona / www.polona.pl

Piłsudski's brain - right hemisphere, lateral part; source: Mózg Piłsudskiego at Polona / www.polona.plPiłsudski's brain was to become the most splendid object of research in this new field of science in Poland. The Marshal, as Piłsudski was widely known, was already considered a genius and a legend by his compatriots during his lifetime. Some of his contemporaries even believed Piłsudski possessed psychic powers such as foretelling future events or predicting the moves of his opponents at chess. While this is naturally pure speculation, Piłsudski’s political genius manifested itself quite clearly during WWI, and immediately after, when Piłsudski became the driving force behind Poland’s independence, which many believe wouldn’t have been possible without him. The legend of Piłsudski's political genius was further corroborated by his later political moves which made him Chief of State and – following the coup d'etat of May 1926 – quasi-dictator of Poland.

The Marshal himself must have shared these most favourable opinions of his mental capacities since he bequeathed his brain to science in his last will, despite his general aversion to doctors and medicine. Immediately after his death, his brain was cast and put into a jar containing formaldehyde and Karlsbad salt. It was subsequently transported to Vilnius, cut into tiny pieces, photographed and subjected to thorough ‘architectural’ examination, in order to shed light on the nature of the Marshal’s genius.

Unfortunately, Professor Rose, head of the research team, died unexpectedly in 1937, leaving the whole enterprise unfinished. In 1938, the results of his work were published in a bilingual Polish-French book entitled Mózg Piłsudskiego (Piłsudski’s Brain) accompanied by an atlas with photographic plates showing layers of the Marshal’s brain. Very few copies of the book were published, and today fewer than 20 invaluable copies remain. See the book Mózg Piłsudskiego at Polona.pl

However, the story does not end there, as the brain itself disappeared in 1939 in unexplained circumstances. According to one theory, it was transported to Warsaw, where it was later destroyed during the war (Berlin and Moscow are also mentioned as possible destinations); according to another theory the brain was buried on the premises of the Institute of Brain Research in Vilnius. In the latter case, let us hope it will never be found...

For more about Piłsudski see Daring Tombstone Reproduction at Biennale of Architecture

Hygiene, Eugenics, Progress

Zuza Ziółkowska, Rassenvermessung, 2014, photo: press release

Zuza Ziółkowska, Rassenvermessung, 2014, photo: press releaseIn Warsaw’s Progress and Hygiene exhibition, shown at the Zachęta - National Gallery of Art in winter 2014/2015, the surviving photographs of Piłsudski’s brain, taken from Maksymilian Rose’s posthumous work, are displayed in a room next to a 1936 pamphlet of The Polish Eugenics Society, a video tutorial on how to change a person’s skin in a portrait using a popular graphics editing program (Bernard Moreau [Tymek Borowski & Paweł Śliwiński] – Skintone Chart) and a series of doll's heads inspired by phrenological charts (Marianne Heske, Heads).

Several other items shown in the same room, like the works of contemporary artists Luc Tuysmans and Magnus Wallin, as well as Dina Gottliebova-Babbit’s painting, bring us to the black heart of the exhibition – the Holocaust.

Gottliebova, who was born in 1923 in Brno, was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau when she was 20 years old. In the camp, Dr Josef Mengele, who had seen one of her drawings, ordered her to paint portraits of Roma people that he later experimented on. Dina survived the war and later moved to the US, where she married the American animator Arthur Babbitt. She went on to work for some of the greatest American animation studios, co-creating characters like Tweety Bird and Daffy Duck. In Zachęta we get to see one of the watercolour portraits painted by Gottliebova-Babbit in Auschwitz, entitled Half-blood Gypsy from Germany.

The Holocaust and racial hygiene are addressed in the work of Krystyna Piotrowska. Piotrowska’s Collection series comprise drawings of eyes, noses and mouths. Conceived as a collection of facial elements which in usual circumstances make up personal identity, these elements cease to characterise the appearance of any particular model once they’re ‘removed from the face’. The noses from Collection No 1 – decontextualized and lined up on paper – call to mind the illustrated albums of racial classification systems used in anthropological research based on eugenic theories.

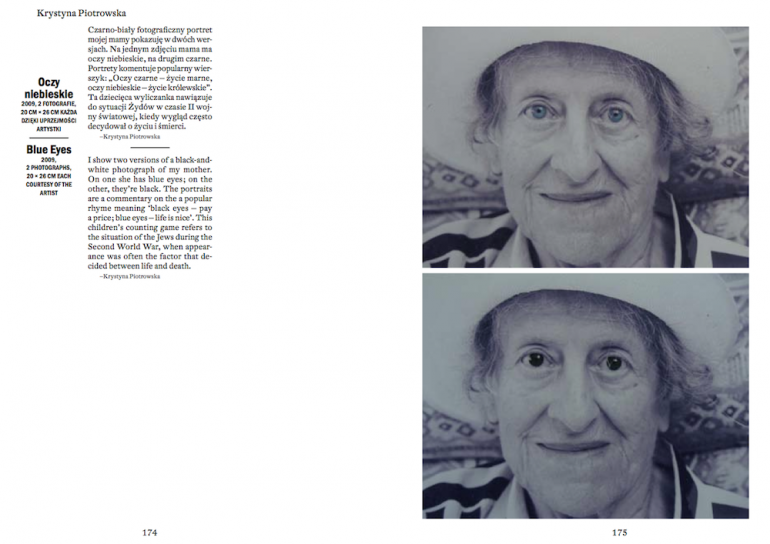

Krystyna Piotrowska, Blue Eyes; Source: catalogue of the exhibition

Krystyna Piotrowska, Blue Eyes; Source: catalogue of the exhibitionAnother work by Piotrowska refers to the Holocaust even more directly, reflecting on the phenomena of outer appearance and physical traits in the context of racial ideology:

I show two versions of a black-and-white photograph of my mother. In one she has blue eyes; in the other, they’re black. The portraits are a commentary on a popular [Polish] rhyme meaning ‘Black eyes – pay a price; Blue eyes – life is nice’. This children’s counting game refers to the situation of the Jews during the Second World War, when appearance was often the factor that decided between life and death.

From this perspective, the photographs of Piłsudski’s brain – turned into a scientific specimen – are seen as part of the same modernist effort to name and measure all aspects of human reality, an approach which served to show qualitative differences between people and individuals, and which later became instrumental in the eugenic and racist practices of the Nazi era. Even though post-mortem research on the brains of so-called geniuses may seem like just the reverse of racial hygiene and human engineering, it can just as well be construed as a shade of the same spectrum, a dangerous tradition which instrumentalises the human being.

Health, Sports, Red and Blue Chair, and the Global economy

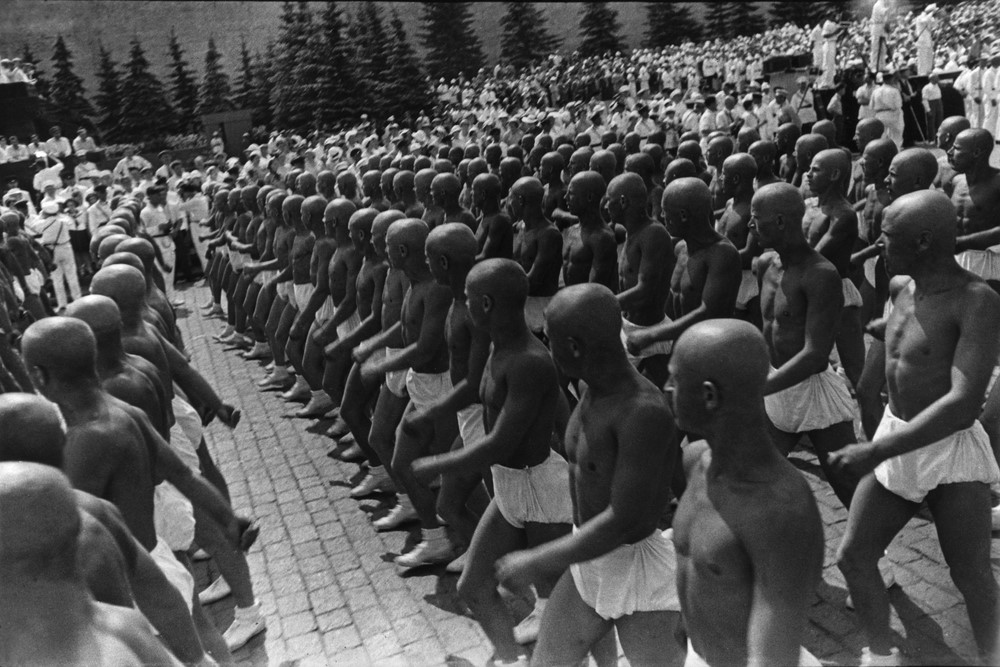

Alexander Rodchenko, Sportsmen on Red Square, 1932, courtesy of A. Rodchenko & V. Stepanova Archive. Source: Progress and Hygiene press materials

Alexander Rodchenko, Sportsmen on Red Square, 1932, courtesy of A. Rodchenko & V. Stepanova Archive. Source: Progress and Hygiene press materialsSimilarly, other rooms of the exhibition offer much thought-provoking matter, even if the connections made by curator Anda Rottenberg seldom strike one as obvious.

A different room examines the idea of hygiene, understood as the health of people, cities and whole societies. The idea is illustrated through the works of Leni Riefenstahl and Alexander Rodchenko, depicting perfect human bodies and perfect bodies of society, respectively. These are exhibited along with photographs by Zofia Kulik (Moon Skull, Leaf) and surprisingly juxtaposed with Gerrit Thomas Rietveld’s arch-Modernist Red and Blue Chair hanging from the ceiling.

Red and Blue Chair designed by Gerrit Rietveld in 1917; source: CC / Wikimedia

Red and Blue Chair designed by Gerrit Rietveld in 1917; source: CC / Wikimedia In yet another room, one can find a monumental new piece by Mirosław Bałka entitled 233906250 cc, a giant, open-ended container made of plywood and steel (the title refers to the volume of the object measured in cubic centimetres). The austere, monochromatic structure is contrasted with Jan Fabre’s colourful works from the Tribute to Belgian Congo series (the colours come from the jewel beetle wing cases which were used by the artist as a material).

The logic of the exhibition will take the viewer in several surprising directions, encompassing various areas of the contemporary socio-political experience, including political manipulation, exclusion, resettlement, trauma, and national identity, as well as surgery, self-identity and global regulations (as described by the section titles of the exhibition).

The Progress and Hygiene exhibition at Zachęta - National Gallery of Art in Warsaw is open until 15 February, 2015

Author: Mikołaj Gliński, 8 January 2015