One Photo One Story: The Round Table Talks

In 1989, after 45 years in power, the communist regime in Poland was in decline. The ruling communist party was like a fighter who had been knocked down several times and awaited the final blow. Yet the Polish walk to freedom was not to be ended by a one-sided, winner-takes-all victory for the democratic opposition. As is usual for Poland, things were much more complicated… Get to know the history of the Polish Round Table Talks below.

How did it come about?

The imposition of the communist regime in Poland was a result of the Yalta Conference and the closing of the Iron Curtain – a border separating the spheres of influence of the two opposing sides of the Cold War. Poland fell on the Soviet side, but just as in many other times in its history, it didn’t accept the role of a satellite country. Mass protests in 1956, 1968, 1970 and 1980-1981 were all suppressed with brutal force by the army and police, but when a new wave of protest arose in 1988, the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) was no longer strong enough to forcefully deal with the opposition. It couldn’t count on Soviet support either. A severe, long-lasting and aggravating economic crisis, as well as the obvious lack of legitimacy of the communist party, put Poland on the verge of collapse. Under these circumstances, the only way out was to talk with those who were supported by the Poles in the late 1980s – the democratic opposition.

The Round Table Talks

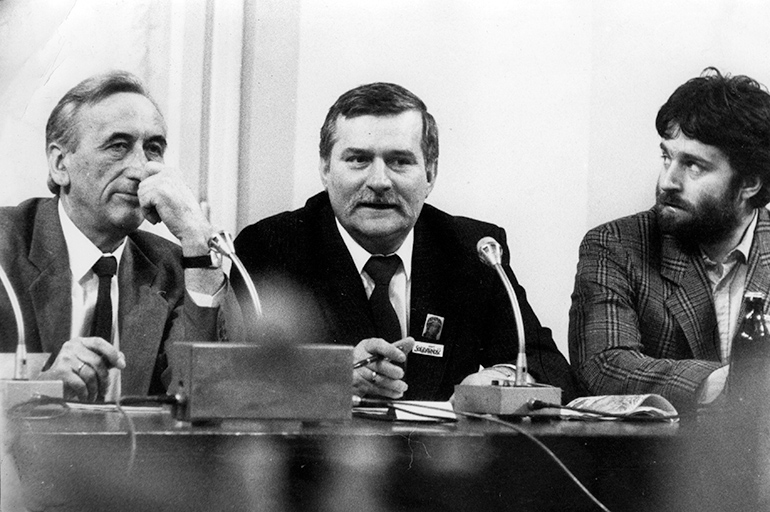

The Round Table Talks, from the left: Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Lech Wałęsa, Bronisław Geremek i Mieczysław Gil, photo: Ania Pietuszko / Forum

The Round Table Talks, from the left: Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Lech Wałęsa, Bronisław Geremek i Mieczysław Gil, photo: Ania Pietuszko / Forum

What is usually believed to have been talks between a handful of leaders of the democratic opposition, PZPR and church representatives was in fact a huge process involving more than 700 people. There were work-groups and commissions with multiple sub-commissions devoted to projecting the transition of specific areas of the political system and economy. Initially, the Round Table Talks were not meant to remove the communists from power, but rather to start reforming the country with the participation of the leaders of the democratic opposition. This is why the provisions might seem not to have been bold enough. According to the Round Table Agreement signed on 4th April 1989:

- Independent trade unions were to be legalised (including Solidarity, which became a legal political force)

- The Senate was to be formed as the higher chamber of the Polish parliament

- The Office of the President, elected by a bicameral parliament, was to be introduced instead of a communist party general secretary

- A semi-free election was to be organised with 65% of seats in the Sejm (lower chamber) granted to PZPR, but a free election for the Senate.

These compromises were the result of both sides' justified fears. The communists had little idea what the result of the free election would be, since such a vote had not taken place in the past 45 years. They still remembered 1980, when Solidarity had 9 million members and almost took power. This is why they sacrificed a lot: leaving the talks with only 65% of the seats and a President chosen by Parliament, not by the people. The democratic opposition threatened to get involved in the reforms only partially, out of fear of being used as scapegoat for the most difficult reforms resulting in further exacerbation of the economic crisis during the first years of the transition. Most obviously, they also feared repressions, remembering how protests and negotiations in 1980 eventually led to the introduction of martial law and the mass detention of its leaders.

Consequences

The Round Table Talks, from the left: Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Lech Wałęsa, Władysław Frasyniuk, photo: Jerzy Michalski / Forum

The Round Table Talks, from the left: Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Lech Wałęsa, Władysław Frasyniuk, photo: Jerzy Michalski / Forum

The semi-free election designed by PZPR as a last resort to stay in power introduced some reforms but turned out to be the final blow to the whole communist political system. Solidarity’s success surpassed all expectations. The candidates of the democratic opposition won 161 places in the Sejm out of the 161 possible, and 99 out of 100 in the Senate. But the real result was even more revolutionary. The communist regime turned out to have no legitimacy to stay in power and, thanks to Solidarity refusing any unfair compromise, failed to establish a new government. Soon, Tadeusz Mazowiecki’s first non-communist government was established and Poland found itself on the beginning of the long and bumpy journey to being a free democratic country with a market economy.

Moreover, the Round Table Talks set off the process known to historians as the Revolutions of 1989. In November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, Hungary sat down to its own round table talks, and the Czech Republic underwent the Velvet Revolution.

Controversy

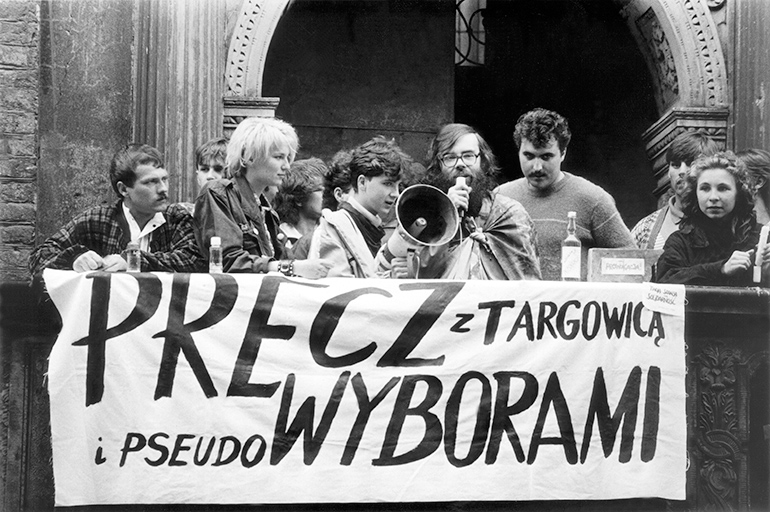

Gdańsk 1989, demonstration against The Round Table Talks, photo: Jan Bogacz / Forum

Gdańsk 1989, demonstration against The Round Table Talks, photo: Jan Bogacz / Forum

Polish opinion of the Round Table Talks was always mixed, just like their opinion of the political transformation in general. Some of the democratic opposition activists claimed it to be a success for the communist side, not for Solidarity. A few even suggested that it was part of a Soviet secret service plot designed to be the guise for the real talks, which they believed had been held before the Round Table Talks and had decided that power was to be divided between them and the communists. Others believe the Round Table Talks to be the biggest success of the whole process of toppling communism. Most likely, there is no unambiguous answer whether there could have been something better than the Round Table Talks, but Professor Karol Modzelewski, one of the most influential democratic activists, who wasn’t personally involved in the negotiations but had first-hand information on everything that happened throughout the process, said:

The black legend of the plot of the Round Table seems really comic to me. In fact there were many plots – both sides were plotting a whole lot but they were plotting against each other. Neither the intentions, nor the results of this plotting remained secret – we know how they were doing it and we know what they achieved (or rather what they didn’t).

Author: Wojciech Oleksiak, 6th May 2015

Sources: inter alia: Karol Modzelewski – 'Zajeździmy Kobyłę Historii, Dominika Kowalska, Wojciech Rogacin – Korespondenci.pl, ipn.gov.pl, Dziennik.pl / Interview with Norman Davies.

Tytuł (nagłówek do zdjęcia)

Hear the Eastern

Bloc's collapse

[{"nid":"5688","uuid":"6aa9e079-0240-4dcb-9929-0d1cf55e03a5","type":"article","langcode":"en","field_event_date":"","title":"Challenges for Polish Prose in the Nineties","field_introduction":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary\r\n","field_summary":"Content: Depict the world, oneself and the form | The Mimetic Challenge: seeking the truth, destroying and creating myths | Seeking the Truth about the World | Destruction of the Heroic Emigrant Myth | Destruction of the Polish Patriot Myth | Destruction of the Flawless Democracy Myth | Creation of Myths | Biographical challenge | Challenges of genre | Summary","topics_data":"a:2:{i:0;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259609\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:26:\u0022#language \u0026amp; literature\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:27:\u0022\/topics\/language-literature\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}i:1;a:3:{s:3:\u0022tid\u0022;s:5:\u002259644\u0022;s:4:\u0022name\u0022;s:8:\u0022#culture\u0022;s:4:\u0022path\u0022;a:2:{s:5:\u0022alias\u0022;s:14:\u0022\/topic\/culture\u0022;s:8:\u0022langcode\u0022;s:2:\u0022en\u0022;}}}","field_cover_display":"default","image_title":"","image_alt":"","image_360_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/360_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ZsoNNVXJ","image_260_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/260_auto_cover\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=pLlgriOu","image_560_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/560_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=0n3ZgoL3","image_860_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/860_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=ELffe8-z","image_1160_auto":"\/sites\/default\/files\/styles\/1160_auto\/public\/2018-04\/jozef_mroszczak_forum.jpg?itok=XazO3DM5","field_video_media":"","field_media_video_file":"","field_media_video_embed":"","field_gallery_pictures":"","field_duration":"","cover_height":"991","cover_width":"1000","cover_ratio_percent":"99.1","path":"en\/node\/5688","path_node":"\/en\/node\/5688"}]