Gabi and Uwe simply could not stop talking to each other. An hour passed, then a second. Their friends had already gone home for the night, and still, they talked and talked. Until sunup.

What was your book about?

It's about my grandfather, who was stationed here in Kraków as a member of the SS…

Oh. You see, my grandfather was killed at Auschwitz.

An hour later, the descendants of an executioner and a victim walked down Szeroka street in silence. In a year, Gabi and Uwe would become husband and wife.

Today, the pair travels around the world and speaks about the necessity of knowing your own history and the ability to forgive. They explain how the past influences the present and the future. Nearly ten thousand people have attended Gabi and Uwe’s lectures recently in the USA and the book about their story and the lives of their ancestors has become a best-seller. Culture.pl’s Evgeni Klimakin sat down with Gabi and Uwe von Seltmann.

Evgeni Klimakin: Like everyone else, I will ask you to tell your story.

Gabi von Seltmann: You know, when I came to this interview, I was thinking about how we tell our story and the story of our ancestors with completely different emotions than we once did.

What do you mean?

Uwe von Seltmann: We do it more calmly.

GS: Yes, we found out the whole truth in order to leave it behind. To allow us to live peacefully, not always to look backwards.

US: Because no one really told us who our ancestors were, how they lived, who they helped or what crimes they committed. We had to travel the world, digging through archives, and bit by bit, we collected information.

What did your life look like before everything was out in the open?

GS: In Poland, there is a saying: ‘sweep it under the rug’, that is, hide anything that is uncomfortable or unpleasant. We lived for a long time with the view that everything was fine, that there was nothing ‘under our feet’, but then the rug was pulled out from under us…

Guilt about old crimes

US: I lived with a feeling of guilt for the crimes of my grandfather for a long time - even though I didn't know anything about him or what he had done. In 1999, I came as a journalist from Germany to Kraków to write an article about the Kazimierz district, where most of Kraków's 65,000 Jews had lived until the war. Stopping by the Remah Synagogue, I noticed a man in a dark suit, who was reading a prayer for the dead. I asked if I could ask him a few questions. He agreed, but then he began posing his own questions.

Why have you approached me?

I am writing a story about Jewish Kraków.

Why are you interested in Jewish life?

I've been interested in Jewish life for a long time.

You could have found Islam interesting, or Hinduism. Why Judaisim?

Perhaps because the Nazis destroyed a unique culture.

Do you feel guilty?

Me? Why should I feel guilty? I'm in my mid-30s.

When was your grandfather born?

I don't know exactly. 1917, I think.

Aha, your grandfather was a Nazi.

Yes, he was in the SS. I don't know anything more than that.

And your father?

1943.

Where? In Kraków?

Yes.

You are interested in Jews because you feel guilty. You feel guilty for what your grandfather did - whatever it was.

Oh, how I hated my grandfather, Lothar von Seltmann, in that moment! Because of him, I suffered from guilt for 20 years. I realised this thanks to this man, whom I approached for my story, but who ended up changing my life.

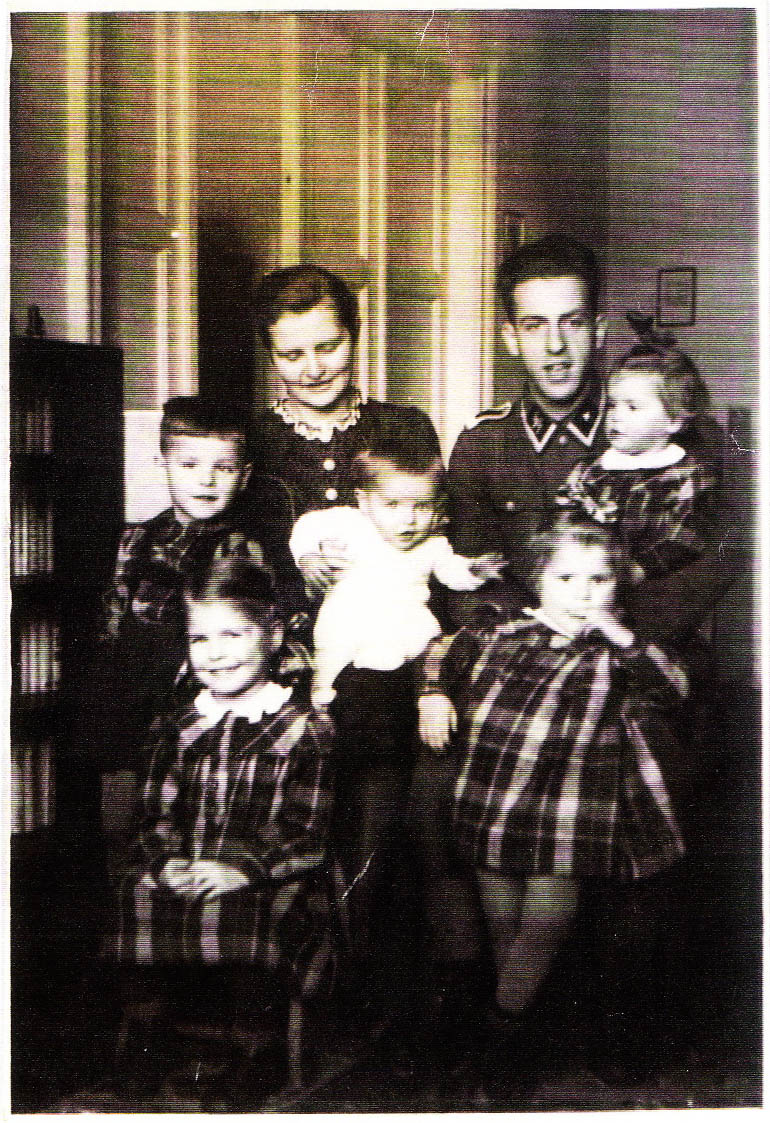

Wilhelmine and Lothar von Seltmann, the grandmother and grandfather of Uwe. After the war, the SS emblem on Lothar’s collar was coloured over, photo: Seltmann family archive

Wilhelmine and Lothar von Seltmann, the grandmother and grandfather of Uwe. After the war, the SS emblem on Lothar’s collar was coloured over, photo: Seltmann family archiveThen, as I understand, your long search began. Uwe, tell me, what did you find?

US: I always wanted to know who my grandfather was, what he did. When I was a small boy, I found my father’s passport. On the line marked ‘place of birth,’ it said ‘Kraków’. This surprised me. I asked him: ‘Kraków? Where is that?,’ ‘In Poland. My parents were living there then. Son, don’t ask me any more about this. I simply don’t know anything,’ my father answered. He truly did not know. By the time my father was 2 years old, my grandfather had already passed away. Nine months later my father’s mother died. My father, his brothers and sisters ended up in orphanages or various foster families. He doesn’t know why he ended up in a small town near Dortmund.

Did your father have many brothers and sisters?

US: Five. The oldest was born in Vienna in 1938 and the youngest in 1945. My father was the second-youngest child. He and his siblings did not know their father was a criminal. I was the one who revealed this horrible truth to my family. I began my investigation when I was 35 years old. Today, even after 18 years, I still sometimes stumble upon new information about Lothar von Seltmann.

What exactly did you learn about your grandfather?

US: The most horrifying discovery for me was that in 1943 he was a member of an SS battalion deployed in the Warsaw Ghetto. He killed Jews fighting in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising... I collected information about him bit by bit. I discovered, for example, that during the war he had been in Lublin, Lviv, Chernivtsi and Odessa. Even before I learned this, without realising it, I had been following in my grandfather’s footsteps. I was drawn to these places.

The fascination with Nazism

When did your grandfather become involved with the Nazis?

US: He grew up in Austria. At the age of 13, he became a member of the ‘Hitler Youth’. When he was 16, he, as a young Nazi, was charged with criminal activity. My grandfather and some like-minded people were suspected of having blown up railway tracks and prepared various kinds of provocations. In 1934, he fled from Austria to Germany and began to study at an elite Nazi school. There my grandfather met his future wife, my grandmother, Wilhelmine Fritsch. We should remember that in 1938 Austria joyfully welcomed the reign of Adolf Hilter and the local Jews there were forced to clean the sidewalks with toothbrushes. After these events, my grandmother and grandfather went to Vienna, not fearing anything. At the age of 22, my grandfather began to work for Odilo Globocnik.

The founder of death camps?

US: Yes, this man was the Commissioner of the Reichsführer SS for the creation of SS structures and concentration camps in the territories of occupied Poland. Globocnik invited my grandfather to work with him and so my grandparents came to occupied Lublin…

From your book Gabi and Uwe, I also found out about how your grandfather worked with Heinrich Himmler.

US: Yes, it’s true. Over the course of his career, my grandfather dealt with some of the most influential Nazis.

Lothar von Seltmann (left) and Heinrich Himmler (centre), photo: Seltmann family archive

Lothar von Seltmann (left) and Heinrich Himmler (centre), photo: Seltmann family archiveUwe, why did the idea of Nazism seize the heart of such a young man? You’ve probably asked yourself this question many times.

US: My grandfather’s parents were very conservative people; they continued to be monarchists in the Austrian Republic after the First World War. For young people, Nazism seemed very modern, even fashionable. When I look at what is happening now in the world, I remember what happened in the 20th century. Today people who don’t want to hate are called 'old-fashioned'. We are all witnessing how nationalism spreads its wings. On the eve of World War II, the situation was eerily similar.

Enjoying spring

While he was in occupied Poland, your grandfather sent his parents letters. What did he write about?

US: Nothing about the war, nothing about how the Germans were turning the lives of millions of people into a nightmare. He wrote about how he was very busy, that he had a lot of work. When my dad was born, my grandfather was in the Warsaw Ghetto. He wrote his mother that he was proud to learn that in Kraków his son had been born. He regretted that he couldn’t be with his family because of an important operation in Warsaw. He also wrote about how a beautiful spring had begun, nature had awoken, but because of work, he wasn’t able to enjoy it fully. It’s chilling because, at this time, he was killing Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto. This was the ‘work’ that was preventing him from enjoying springtime and being with his new-born son, my father…

What did your grandfather do in occupied Poland before he became a soldier in the Warsaw Ghetto?

He worked in propaganda. He published a propagandist journal. He also was responsible for finding people with German roots. The Third Reich thought that these people must be supported. That was his job: saving ethnic Germans and sending them back to Germany. At the same time, this also meant imprisoning or killing Poles and Jews.

What do you think about the responsibility of those who worked in propaganda?

It is a serious crime. Propaganda is the foundation on which various terrible things can be built. Hitler couldn’t have implemented his nightmare without propaganda. There is no doubt that propagandists are criminals who must be held responsible for their crimes. George Orwell once wrote that truth is the first casualty of war. When I read about journalists in our day who are put in jail or killed for their professional activities, it’s clear to me that Orwell was right.

Where did you find information about your grandfather?

Lothar von Seltmann with his wife and children. Christmas 1943, photo: Seltmann family archive

Lothar von Seltmann with his wife and children. Christmas 1943, photo: Seltmann family archiveUS: In archives in Poland, Germany, the United States and Israel. I gathered information from wherever I could. I managed to recreate my grandfather’s life. For example, I discovered that in February 1945, he killed himself. Shortly before his death, he met his wife’s sister, showed her a pistol, and said that in the event of a Red Army victory, he knew what to do. I would like to think that he regretted his crimes, but I am afraid it was the opposite. When the SS killed half a million Hungarian Jews in 1944, he was happy. Lothar von Seltmann then wrote: ‘Finally they are killing the last Jews of Europe.’ The irony of fate – my grandfather possibly also had Jewish blood.

He did?

GS: In 2011, we were invited to Hungary for an author’s conference. We didn’t remember what time it started, so we decided not to bother anybody and just check on the internet. Uwe entered two words into Google: ‘Seltmann’ and ‘Budapest’. We were shocked when we saw the link with information about a Seltmann who was Jewish – a Hungarian chief rabbi. It turns out that part of Uwe’s family is originally from Hungary. Some of them were baptised and moved to Vienna. All of the Jewish Seltmanns were killed during the war. We don’t know if Lothar von Seltmann himself knew of his Jewish origins.

A fateful meeting

The story of Uwe’s grandfather is described in the book ‘If The Perpetrators Will Not Speak, Their Grandchildren Will,’ which became a bestseller in Germany. Soon afterwards, your fateful meeting happened. Tell me about how you met.

Uwe and Gabi von Seltmann, photo: Adam Golec

Uwe and Gabi von Seltmann, photo: Adam GolecUS: I sometimes guide tours from Germany around Ukraine. I show Lviv, Chernivtsi…. In 2006, returning from one of these trips, the group and I stopped for the night in Kraków. That night, I went to the Singer café.

GS: I was there with friends at the time. We were joking, drinking wine. Then Uwe, who was sitting at the next table, offered to take a photo of us. From his accent, we immediately knew he wasn’t a Pole. Uwe came to sit at our table and started to talk. He was very interesting! We asked him a lot of questions and then he admitted that his grandfather was in the SS. It was a shock!

Gabi, what did you feel when you heard this?

GS: It felt like an axe had struck my head. And I just blurted out ’And my grandfather was killed in the Auschwitz concentration camp.’ There! It was difficult for me to control my emotions. But then I understood that this was a man who was trying to do something with his family's terrible past, who wanted to sort everything out. I had never before met a person who could talk so openly about such things.

Gabi, what do you remember most of all from that meeting?

GS: I remember everything. I will never forget the anger I felt then. At dawn, Uwe and I were walking near an old Jewish cemetery and I thought: ‘Why is this happening?’ I met a good, intelligent man – who cares about what our ancestors did. He and his grandfather are two different people. I understood this, but then I couldn’t do anything about the anger in my heart. Two weeks later, Uwe came back to Kraków. He liked me. I thought: ’Interesting man. He must either be married or gay.’ Luckily for us, I was mistaken. Our relationship developed rapidly and within the year we became husband and wife. Meeting Uwe was an important signal for me: thanks to my husband I understood that it was time for me to learn about my own story.

Gabi and Uwe’s wedding, photo: Seltmann family archive

Gabi and Uwe’s wedding, photo: Seltmann family archiveThe story of your grandfather?

GS: Yes. My mother didn’t let us go on school trips to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. She thought that she was protecting us and herself from the awful truth, from this tragedy. If you don’t know, you don’t see, you don’t think about it, then you will sleep peacefully. I realised that this was not the right approach.

How did your family react?

GS: Without enthusiasm.

Taboo subject

Uwe, how did your family, your father and his siblings, react to your desire to know the truth?

US: The ones who remember anything were categorically against it. They wouldn’t tell me anything. Some of the others understood that it was important. After my book came out in Polish, one Polish woman reached out to us. She wrote: ‘I recognised the room where I grew up from a photo in your book. Your grandfather’s family lived there. If you want to drop by, just write. It still belongs to us.’ And so my father and some of his siblings came to Kraków to visit the apartment where they had lived as children.

Izabela and Michał Pazdanowski, Gabi’s grandparents, photo: Pazdanowski family archive

Izabela and Michał Pazdanowski, Gabi’s grandparents, photo: Pazdanowski family archiveGabi, your grandfather also lived in Kraków.

GS: He was an impoverished member of the gentry, a native of Kraków. He received his education at the Jagiellonian University and studied in Switzerland. Then he moved to Verkhovyna, which was then located on the eastern frontier of Poland (it is now in Ukraine). In 1935, he built an agricultural school for Huculs and became its director. Interestingly enough, the building is still standing. Even some photographs survived. The regional hospital is there now. When I arrived, I became acquainted with Pani Wasielina, who told me about my grandfather. He was a big admirer of Hucul culture and traditions. This question was pestering me: what kind of man was he? The naked truth is that at that time some Poles behaved horribly in that part of the country.

What was your grandfather like?

GS: While studying the history of my grandfather, we found denunciations of him in an archive.

Who wrote them?

GS: Poles. The Poles were upset that he didn’t try to polonise the local Ukrainian community. Uwe once told me that I was lucky to have such a grandfather. He was a good man.

What did your family do when the war began?

GS: In 1939, my grandparents gathered their belongings and decided to return home with their two children. My mother was not yet born. On the road, their daughter, my aunt, began to cry. My grandparents thought about it and then turned their cart around. They returned and then horrible things began to happen in Verkhovyna.

The school where Michał Pazdanowski, Gabi’s grandfather, was the director, photo: Pazdanowski family archive

The school where Michał Pazdanowski, Gabi’s grandfather, was the director, photo: Pazdanowski family archiveLike what?

GS: Up until 1941, Soviet troops were stationed there. As the locals say, the Soviets almost immediately killed all of the influential Ukrainians. Then came the Germans. My grandfather was arrested and deported in 1942. They arrested Poles who were directors, supervisors, Catholic priests. They were often turned over to the Germans by local residents. At first, they transported my grandfather to Kolomyia, then to Stanisławów (Ivano-Frankivsk), then to Lviv. He was put in the Majdanek concentration camp and then, finally, he was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he died. At the same time, in Verkhovyna, all of the Jews were being killed. They were simply taken into the forest and shot.

And what happened with your grandmother?

GS: Then the period of activity of the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) began. They tried to kill my grandmother several times. Luckily, one Ukrainian schoolteacher warned her about the approaching danger. She managed to run away with her children in 1943. Since then, none of us had ever returned there. I was the first to do it. Ukraine was a taboo subject in our family. Verkhovyna was a cursed place for us. However, I have constantly asked myself the question: if it was such a cursed place, then why did my grandparents live there, why did they return there? It mustn’t be so terrible. So, I decided to go.

First meeting with the past

But you didn’t know anyone there?

GS: We first became acquainted with Anna, who spoke Polish and then we began to go around, knocking on doors, showing pictures of my grandparents and asking people if they knew anything about the Pazdanowskis. Later some people called and informed us there was a woman named Wasielina who lived near the school and may be able to help. She was already 85 years old at that time.

Wasielina and Gabi. First meeting, photo: Seltmann family archive

Wasielina and Gabi. First meeting, photo: Seltmann family archiveYou went to her…

GS: We showed her a photo and she immediately said: ‘This is Michał, this is Isabella’ – she knew instantly. I will never forget that day! In the Ukrainian hills, I met an old woman who knew my story better than I did. I was so nervous! My hands were shaking, we all wept like children. Pani Wasielina kept saying: ‘Where have you been for so long? Why did you not come earlier?’ During the war, my grandmother lived in Verkhovyna, half-starving. Once Wasielina came home and saw that Isabella, who was left alone with three children, only had a few beets in her home. She told her grandmother and she started to give Wasielina food, which she would secretly bring to our house. Wasielina practically saved my family from starving to death. Every day at dawn she brought my grandmother food and then quickly ran away so that no one would see. Wasielina’s father was in the UPA, and of course, he didn’t know anything about it. You understand how complicated and multifaceted history is? Can you imagine, what this meeting meant for me?

Is Wasielina still alive?

GS: She passed away in 2015. She waited for four years to meet my mother.

She waited?

GS: Yes. My mother was just a small child when all of these nightmares happened in Verkhovyna. She doesn’t remember anything but she inherited some sort of genetic fear, frustration. My mother is a shining example of a person who for decades bore the brunt of tragedy, the severity of the experiences of the previous generation. She doesn’t remember my grandfather being arrested, people from the UPA coming. She didn’t really see anything but she spent her whole life with the burden of other people’s troubles. I tell people about her, who say, that it’s not necessary to stir up old matters, that you need to forget about everything and not to pry into the painful past. This isn’t true! The past actively affects us, our life today. You should’ve seen how afraid my mother was of going to Verkhovyna.

But she did.

GS: I convinced her. We went to the house where our family had lived. Now a schoolteacher lives there, Pani Maria. She welcomed us very warmly. Pani Maria asked my mother to spend the night. Honestly, she did not want to, but I insisted. I knew that my mother needed to overcome her fear, that she needed to be in the house where she spent the first year of her life. My mother couldn’t fall asleep for a long time. Then Pani Maria went to the garden, picked a few herbs, made tea and after that, she fell asleep. My mother woke up a different person! Our whole family felt that mother changed. The terrifying history, which constantly made itself felt, was finally closed.

And what did you feel when you first went to Verkhovyna?

GS: I was also afraid. Uwe almost had to bring me there by force. What was I afraid of? People with guns or axes? But this was just nonsense. I understand, that it is an irrational panic, fear. You realise, that nothing bad will happen but still nothing can be done about it. It is locked in somewhere in the subconscious. Places trigger memories.

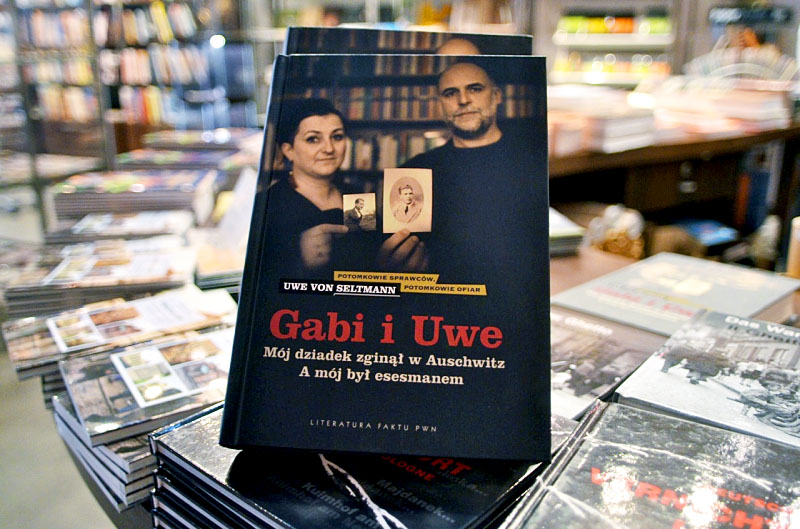

Gabi and Uwe, the book about Gabi and Uwe’s life and their ancestors, photo: Seltmann family archive

Gabi and Uwe, the book about Gabi and Uwe’s life and their ancestors, photo: Seltmann family archiveWhat do you mean?

GS: My first night in Verkhovyna I woke up at 3:00 in the morning. Panicking. It seemed to me that someone was coming, that somewhere far away there was talking, that the gate was being opened. Later, I found out that my grandfather was arrested at 3:00 in the morning. The place where this happened triggered my subconscious. I overcame this fear and it became easier. I was also afraid to go to Auschwitz. Only at age 39, thanks to my German husband, I decided to go to the place where my grandfather was killed. I realised that the Auschwitz concentration camp is a teacher. Auschwitz shows the truth about us, people.

Memory is a saviour

What do you think today about the horrible events of the 20th century?

GS: Every nation has some sins on its conscience. Poles have their own, Germans have their own, Ukrainians and Russians have their own. Every nation also has trauma. Someone who thinks that forgetting or silence heals is gravely mistaken.

US: In 2011, the inhabitants of a village in northern Japan were taught the importance of memory. In many places on the shore stood rocks on which centuries ago, someone wrote how to act during a tsunami. Unfortunately, the advice of ancestors became overgrown with weeds and was forgotten. Because of this, during the 2011 tsunami thousands of people died since they didn’t know what to do during a catastrophe. Only in one small village Aneyoshi, no one died. Everyone there knew what was written on the rocks. They even told children about it in school. Thanks to this awareness, all of the villagers managed to hide in the mountains.

Memory saved them.

US: Japanese professor Fumihiko Imamura who researches natural disasters, says that memory about such terrible events, catastrophes begins to diminish in the fourth generation. Now at their desks in schools sit the fourth generation after World War II. I want to ask people who talk about the need to forget everything: are we raising cannon fodder for the next war? Peace and freedom are not given to be taken for granted. To keep harmony, we must talk and listen to each other and remember the price that humanity pays for the inability and unwillingness to understand each other.

How else does the past affect the present?

GS: For example, in my family, the women do not have children. My grandmother, fleeing from Verkhovyna, lived through a terrible shock, fear for her children. My mother never got over this fear for a large part of her life. As a result, the generation of grandchildren can’t continue the family line. Incidentally, this is a very typical situation for such families. How can it be explained? Whether we want to or not, we are reaping the fruits of the past.

Often without realising it.

GS: Yes. For example, descendants of victims often suffer from depression, they have suicidal tendencies. They themselves don’t understand what is wrong with them. This is a fact. If you feel heavy or anxious and if you know that someone of your ancestors had a difficult life, you must learn more about your parents, grandmothers, grandfathers, their life. Your problems, the problems of your loved ones can be buried in the past. After all, someone in the family must break the chain that transfers the subconscious fear, depression, phobias. Meanwhile, descendants of perpetrators often move around. Uwe lived in thirteen different cities before he met me. The descendants of criminals subconsciously run, constantly hiding from something. Coming to terms with the past is just as needed by the descendants of perpetrators as by descendants of victims. It’s no secret: the descendants of victims can also be aggressive. I am not tired of repeating, that we need to study the past even if for healthy egoism. Each of us has only one life. It’s worth living it happily. It seems to me, that murders and victims are only in the first generation. In the second, third – everyone is a victim. We need to remember this.

US: I want to say one more important thing. For me, the story of my grandfather is closed. it has been dealt with. I live without a feeling of guilt but I do have a sense of responsibility. When I look at our world and what is happening in it right now, I understand that we live in a very explosive environment. A people’s democracy is the last chance to keep something very bad from happening. The situation in the world resembles what was happening on the eve of World Wars I and II. Free, open, tolerant people must stop nationalism. Nationalism always leads to conflict and war. Never forget.

Learn more about Gabi and Uwe’s activities on their foundation’s website: www.aha.org.pl.

Originally written in Russian, 24 Mar 2017; translated by KA, 6 Apr 2017