DS: You were born and raised in the Vilnius region, which back in time was part of Poland, when suddenly the Second World War broke out. The stories of other refugees may vary, but you all met in Tehran, from where the journey integrated you into a small society. Do you remember your prologue to this unbelievable route, the significant day when your life was about to change and there would be no way back?

AŻSB: It was in 1939. My sister and I were at my grandfather’s home in Truszeliszki. We used to spend all our summers there. I was 13 and Alunia was one year older. I remember that granddad had this small radio, which was kind of expensive back then. I didn’t understand much. All the men and women from the neighbourhood were gathered around this silly device with their ears almost glued to the speaker. The information hit us like a bombshell. But on the radio they didn’t give what was happening to us straight. They said that it wouldn’t last, that we would win and it was only temporary. Men started to join the army. The village was more and more feminine. We started doing the men’s work. Then Soviet soldiers started to visit our village. They came and took whatever they wanted. They cooked in our kitchen, and we had to be quiet and invisible.

DS: And finally you ended up in a Soviet labour camp in Siberia. Do you remember this particular moment?

AŻSB: It was when summer changes into autumn and fields are full of golden crops. I don’t remember the date, it was still 1939. My sister and I were at my granddad’s home. We were working in the field with him, it was surrounded by the forest. All of a sudden granddad stopped working. I saw soldiers coming out from the forest with rifles, rapidly approaching us.

I didn’t know what happened but my body knew and suddenly I started to cry. My sister also was crying. They said: you have 15 minutes to pack. The only one who was thinking clearly was our granddad. He was the bravest. He packed for us. He remembered the First World War, maybe that's why he kept a sober mind. He even hid some keepsakes for us.

DS: But because of his age he stayed in Truszeliszki?

AŻSB: Yes, they didn’t want old people – they were useless. So he packed for the three of us. My mum, my sister, and me.

We travelled in a crowded truck, then by train, and finally we got to Siberia. Well, when we first arrived, we were surprised by the reaction of the people who were already there. They thought that we were a sign of change, that we were there to help, to establish some kind of civilization.

DS: How was the first night? Did you sleep at all?

AŻSB: We were so exhausted. I really wanted to sleep, although the floor was so dirty and we only had a very thin blanket. I couldn't. Not because of fear, emotions, or something. Because of bed bugs. They were all over the place. I didn't know about them before. I was staggered, I kept flicking them off all night long. And every single night it was repeated, but I started not to notice them. The tiredness was too great to have time to think about those creepy creatures.

DS: What could a teenage girl do in such difficult conditions? What was your work like?

AŻSB: There were big trees, huge ones, very beautiful. The men cut them down and the rest had to cut them into pieces. We sat next to a fallen tree and cut it with a saw. From one side to another. Once it was so cold that I couldn’t feel my fingers, I couldn’t feel my body, and I passed out. When I woke up, I touched my face and noticed that my tears had turned into little balls of ice.

DS: Let's travel in time a bit. Suddenly, there was a possibility of leaving the gulag.

AŻSB: Nowadays, lots of students and young people are dreaming about trips like this. But when you travel as a refugee, it's not fun at all. We left the camp, stayed in Bakchar for some time and then our dad joined us and we started our odyssey. There was a train, and getting to this train was the most important thing.

From this particular moment, time and space start to expand and shorten in Anna's words. The story stops and starts without time frames. It loses its linearity and begins to look like a star constellation or electrons circling an atom.

DS: Can we dig more in your memory? What is your most vivid memory from this odyssey that started deep in Siberia?

AŻSB: I remember the road. Trucks, sand, camels, tricky roads, and the beautiful Shah's palace. They'd converted two old, rusty barracks for us. It was in 1942. I remember hundreds of children. Paradoxically, it's a very nice memory. For the first time in a very long time, we were able to play, to be kids. I remember that in Tehran they really took care of us; we were even invited to sing for the Shah. We were able to participate in daily mass. Also, I remember the view from the rooftop of the Shah's palace – an amazing city of precious gardens. It was like a city from a fairy tale. Also, I have never seen such beautiful carpets.

I smile, and Anna notices.

AŻSB: I know it might be funny that I remember carpets, but when among all the dirty and dark stuff, something nice occurs, it just sticks in your thoughts.

DS: Memory can be fickle – I know that the mind can be very selective. I'm not laughing, don't get me wrong. Let's go back until 1942. You could pick a place to settle during the war, to wait it out.

AŻSB: Mumbai was nothing like my time in Tehran. It was very busy, very loud, very dirty. There was too much of everything. I remember two things. First, that we had to choose where to go and second, that other Poles joined us. And with them, their terrifying stories. Some of them came over the mountains, other followed almost the same way as we did, some had been living on the streets of Mumbai for a long time.

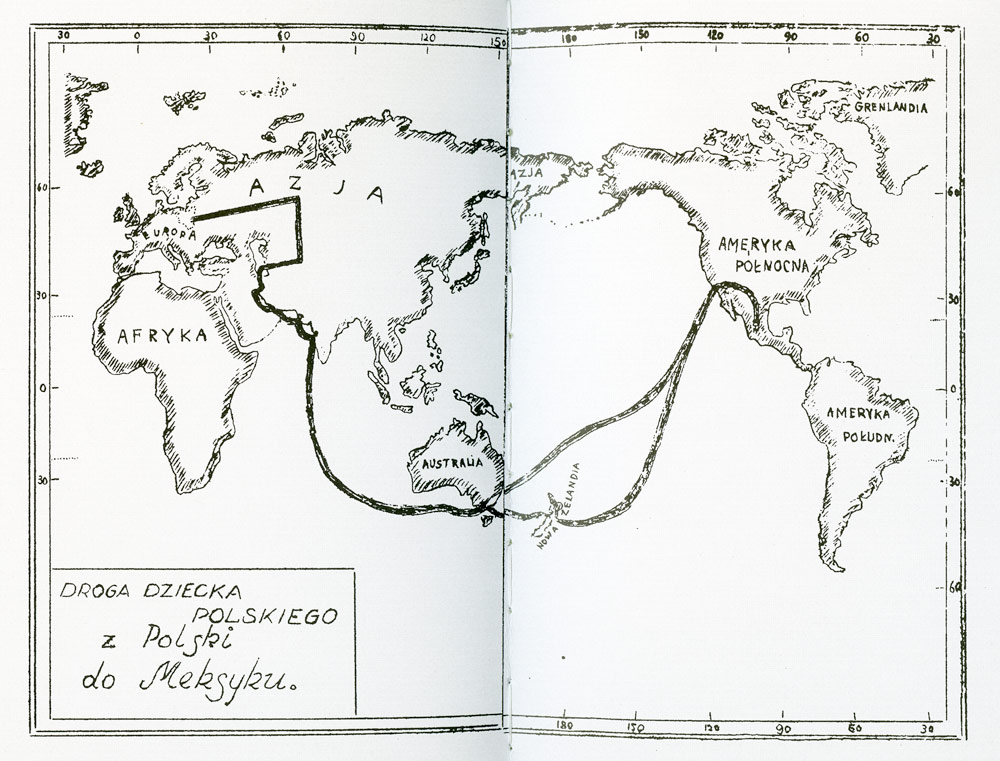

The route of Polish refugees, scan from the report about Hacienda de Santa Rosa, León 1943.

The route of Polish refugees, scan from the report about Hacienda de Santa Rosa, León 1943.DS: Your family chose Mexico. How come? What was so convenient about picking a land so far away instead of closer places in Africa?

AŻSB: I was young, and my parents took care of this decision. I remember that there were lists and you could choose between Mexico or some place in Africa. My dad had a cousin in Chicago – he'd emigrated after World War I. Mexico is in America. We thought that the distance between two places in America couldn’t be so big. My dad said that we'd have nobody in Africa, and that it was always better to have a friendly face around.

DS: About 6,000 km away?

We laugh for a while.

AŻSB: Yes, but we didn’t know it then. I know now how uneducated and stupid I was. But our impression of Africa at that time was worse. A wild land. But I know other refugees who landed there and there are very educated now and happy. And America? We had read 'Uncle Tom's Cabin'…

DS: From Mumbai, you went to Mexico passing through Australia, New Zealand, and Los Angeles in the United States. Finally, you got to the ‘promised land’. I heard that you were more than welcome there.

AŻSB: Oh, it was amazing! After all of these roads, ships, trucks and so on, and so on. We got off the train and mariachi were playing our national anthem, the entire city was covered with red and white decorations. It wasn’t paradise, but it was a nice difference from what we saw before. 'Everything will be alright Anna, everything will be alright, I thought.

Children from kindergarten in Santa Rosa, 1944. Photo: Anita Paschwa's private archive / Kresy Siberia Virtual Museum

Children from kindergarten in Santa Rosa, 1944. Photo: Anita Paschwa's private archive / Kresy Siberia Virtual MuseumDS: You've mentioned the construction of Santa Rosa before. You thought that you would go back to Poland after the war. You spent 3 years there. You arrived a teenage girl and became a woman there. Could you say something more about life in Santa Rosa?

AŻSB: It was three years. It all stopped in 1946 with the end of the war. We had a school there, a theatre, men were making shoes, and we had gardens. Lots of things happened there but it was home.

I remember all of the traumatic events, but I decided to leave them behind on the way.

DS: I will ask one last question. It’s a question that is very often asked in Europe right now: what is it like to be a refugee?

AŻSB: Being a refugee is a disaster. It’s a great tragedy and it doesn’t matter what you think about your country. You love it or hate it, doesn’t matter. Disaster. Wars should never ever happen.

I've lived most of my life in Mexico, but I still remember landscapes from Poland. For me, time stopped that moment when the soldiers came out of the forest. I know that Poland is changing, I see it happening.

I notice changes in Mexico, although I'm getting older and older.

I can’t think about Poland differently. My Poland is that Poland. For every refugee's homeland stays still in time and space without changing. We, the refugees, keep these particular memories.

Or maybe I am just too sensitive…