Aleksandra & Daniel Mizieliński

Daniel Mizieliński & Aleksandra Mizielińska, photo: Krzysztof Dubiel for the Polish Book Institute

Daniel Mizieliński & Aleksandra Mizielińska, photo: Krzysztof Dubiel for the Polish Book Institute With degrees from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, Aleksandra and Daniel Mizieliński have been making waves as a dynamic graphic design duo. Their books from their S.E.R.I.A. (S.E.R.I.E.S.) collection and their Mamoko series have received numerous awards and widespread critical acclaim. In recent years, their book Maps, which contains 51 large format illustrations of maps that show 42 countries from six continents, was in the New York Times’ top six most beautiful graphic children’s books of 2013 and has sold over three million copies worldwide in 25 languages.

The Mizielińskis’ colourful, intentionally naïve and childish drawings take on a life of their own, pleasing both adults and children with their charm. As the artists put it, they create things they would want to use themselves: when they need a font, they simply design it themselves, and when they want to play a game, they invent it.

Zofia & Oskar Hansen

Zofia & Oskar Hansen, photo: Hansens’ family archive

Zofia & Oskar Hansen, photo: Hansens’ family archive Zofia Hansen met her husband, fellow architect and artist Oskar Hansen, when she was a student at the Warsaw University of Technology. Even though Zofia and Oskar Hansen worked together on many projects, critics and journalists frequently ascribe their achievements solely to Oskar. However, Oskar Hansen always emphasised that Zofia was an outstanding architect in her own right. In both their relationship and work, Zofia never played second fiddle to Oskar.

Together, the Hansens co-created the Open Form theory. The idea of Open Form is considered the most important modern school of thought in Polish architecture. According to the theory, artworks and architectural objects should be realised with the people who will interact with it in mind. They wanted the user to have a say and to be a part of the design process, or to be able to finish and change it after the architect designed the initial framework. This was the Hansens’ way of rebelling against ‘closed’ art forms, in which the user had absolutely no say.

Katarzyna Kobro & Władysław Strzemiński

Strzemiński, Kobro, Chałupy, photo: Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Strzemiński, Kobro, Chałupy, photo: Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński were at the forefront of the artistic movement called Unism, which was a creation of Strzemiński’s. Although many remember Strzemiński and praise him while ignoring Kobro’s work, Strzemiński was convinced of the uniqueness of her talent and demanded that greater attention be paid to her art. They had to move around a lot during the world wars and as a result, the majority of Kobro’s sculptures and paintings were lost forever. The couple separated after World War II.

Kobro and Strzemiński strongly believed that each piece of art should be internally sound and constructed according to the rules which governed the particular field. Through Unism, the couple combined the background and the shape to create one original idea in their sculptures. Kobro’s work, which was perceived as controversial during the Interwar period, was equally mistrusted after 1945. Despite the artist living in Strzemiński’s shadow for most of her life, Kobro’s works are now appreciated for their true value.

Hanna & Gabriel Rechowicz

Hanna & Gabriel Rechowicz, early 1960s, photo: courtesy of Kolonie Gallery, Warsaw

Hanna & Gabriel Rechowicz, early 1960s, photo: courtesy of Kolonie Gallery, Warsaw Although the couple often worked in different fields, Hanna and Gabriel Rechowicz made some of their finest works in tandem. The couple met during World War II but officially came together in Paris, where they both studied at École des Beaux-Arts; they later attended what is currently the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk. As Gabriel started to pave his own way as an architect, Hanna was working as a set designer. But it was their work together on décor that made them a famous power couple.

Architectural decorations were the most significant part of their artistic output. They used various methods, usually combining creating mosaics (utilising simple, inexpensive materials, such as pebbles or glass) and wall paintings. Gabriel would do most of the actual designing, but Hanna’s experience with scenography was crucial to their success as designers and artists.

Tadeusz Kantor & Maria Stangret

Maria Stangret & Tadeusz Kantor, photo: © Maria Stangret & Dorota Krakowska

Maria Stangret & Tadeusz Kantor, photo: © Maria Stangret & Dorota Krakowska With Tadeusz Kantor directing and Maria Stangret on the stage, the couple was at the centre of Poland’s theatre world. They were married in Paris in 1961 after a trip to the city. Stangret participated in many of Kantor’s plays and performances, as well as in all of his happenings – including Cricotage (1965), The Letter (1967) and others. After Kantor’s death in 1990, the Kantors’ house in Hucisko was turned into a museum devoted to the legacy of both artists.

Kantor was inspired by Constructivism, Dada, Informel art and Surrealism, which can be seen in both his staging and his paintings. When Kantor introduced Stangret to international avant-garde trends, she began to paint in the Informel art style, which she used to call ‘gestural paintings’. Their complementary styles made for great collaborations.

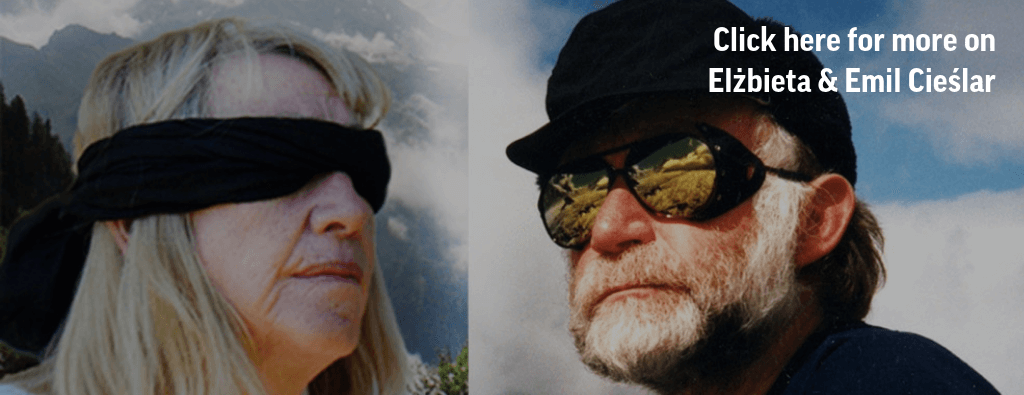

Elżbieta & Emil Cieślar

Elżbieta & Emil Cieślar, photo: courtesy of the artists

Elżbieta & Emil Cieślar, photo: courtesy of the artists Sculptors, designers, performers and more, Elżbieta and Emil Cieślar worked on numerous commercial projects before designing their most famous exhibitions together. In 1963, the couple were two of the founders and leaders of the Industrial Form Designers’ Association. When they took charge of the Repassage Gallery in Warsaw in 1973, they started to focus on sculpture as a method of reaching out to another person.

Largely steeped in the tradition of the modern avant-garde movement, with its progressive, social and inquiring ethos, the Cieślars wanted their works to have an emotional effect on the viewer. Their sculptures questioned the idea of art as an institution, instead seeking to break down the border between the artist and the viewer. This connection to their audience led them to make more politically charged works later in their careers.

Stefan & Franciszka Themerson

Still from ‘Themerson & Themerson’, directed by Wiktoria Szymańska, 2011, photo: Krakow Film Foundation promotional materials

Still from ‘Themerson & Themerson’, directed by Wiktoria Szymańska, 2011, photo: Krakow Film Foundation promotional materials Stefan and Franciszka Themerson bring two art mediums to their cooperative works: writing and painting. With these two skills on the table, some of the most famous Polish animated films were created with the Themersons at the helm. They received acclaim for their film Europa, based on the futuristic poem by Anatol Stern, and went on to make animated staples like The Eye and The Ear and Calling Mr. Smith.

With Stefan continuing to push the boundaries of prose, Franciszka’s illustrations for the films would do the same for film. Europa’s dynamic collage montage, constructivist form and its Dadaist and surrealist iconoclasm ran counter to syntactic rules by which cinematic language functioned at the time. Their contributions to the history of Polish animation will always be considered groundbreaking.